“Hoax,” “conspiracy,” “bias,” “yellow journalism,” “propaganda”: these terms are used perennially by journalists, politicians, and the public alike, but none more so recently than “fake news.” Claims about the influential role of “fake news” in the 2016 Presidential Election necessitate an inquiry into who uses this term, how often, in what venues, and about which sources and topics. Rather than evaluating news content for its accuracy, we approach the circulation of the term “fake news” here as a rhetorical device, used to make political assertions about the truth of various stories and sources. By analyzing both traditional media (print and television news) as well as social media (Twitter), we attempt to paint a broad picture of the information ecosphere immediately following the election and chart the course of “fake news” within it.

Journalistic objectivity

Appeals to “fake news” in the 21st Century should be understood within the context of journalistic objectivity, a concept that Ward (2004) describes as having six features:

- factuality

- fairness

- non-bias

- independence

- non-interpretation

- neutrality and detachment (19).

Though these features are now commonplace in the rhetoric of journalism within democracies, Ward traces the long history of their development over several centuries, culminating only in the twentieth century and only for a few decades. Jensen (2006) is critical of this relatively recent concept of professional neutrality—one that he terms a “myth”—claiming impartiality simply sides with status quo politics. Both Jensen and Ward point to previous eras in which partisan journalism was commonplace and there was no expectation of impartiality in reporting.

Ward credits the seventeenth century with creating printing mechanisms independent of church and state, one capable of providing the public directly with information—albeit partisan and occasionally checked by press controls. By the eighteenth century, the press emerged fully as a “fourth estate” operating in the public interest and “part of the people’s self-governing process” (171). With the rise of nineteenth-century “objective society” (impersonal, science-based, and focused on fair procedures), journalism also developed a fact-based approach, run by independent professionals operating under a burgeoning ethic of objectivity.

By the mid-twentieth century, objectivity was in full swing, a response “designed in part to persuade governments and the public that journalism could regulate itself” (223). This ideal, however, conflicted occasionally with the idea of journalism as a watchdog of governments, and as new media, particularly broadcast journalism, arose, it took on an increasingly personal tone and interest-based reporting, resembling the partisan newspapers of the nineteenth century.

The twenty-first century, especially in light of social media, presents new problems for the concept of journalistic objectivity: what is to be understood as reporting today? who counts as a reporter, falling under whatever professional ethics can be said to exist? how does distribution of information by large numbers of citizens figure into the responsibility of journalists in reporting?

The 2016 Presidential Election

In the months following the 2016 Presidential Election, there was widespread discussion of “fake news” within journalistic and popular sources. Several academic panels and papers (Alcott & Gentzkow 2017; Teixeira da Silva 2017) have already begun addressing the role of fake news in the election. Two Pew Internet studies are particularly relevant in understanding human information behavior leading up to the election.

A December 2016 Pew report on fake news found widespread belief that fake news causes confusion, though U.S. adults also reported general confidence in their ability to identify fake news. About one-third reported seeing fake political news online and nearly one-quarter said they shared fake political news online.

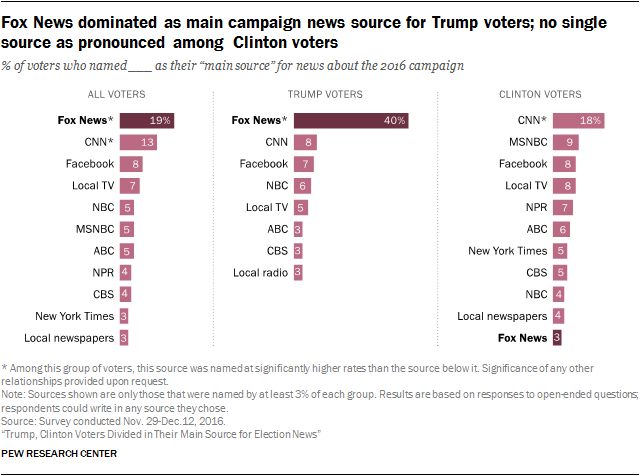

A January 2017 Pew study of information sources by voting patterns found that Clinton and Trump voters differed in their sources for news.

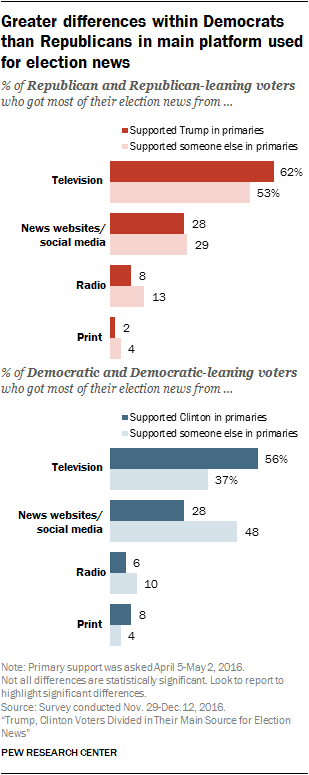

In addition, that study found that Democrats and Republicans differ in the platforms they use to get news:

Taken together, these two Pew studies suggest that a broad study of “fake news” surrounding the election is needed, and that it should include both traditional journalism (print and broadcast) as well as social media.

A discourse analysis

There are several ongoing attempts to define and classify fake news and determine the means by which it is generated and transmitted. While we regard these as important, we are interested, here, in the “fake news” discourse—the ways in which this term circulates in the period immediately following the 2016 Presidential Election. The project relies on evidence of “fake news” as a mutable term in the wake of the election, moving gradually from a qualifier for unfactual information towards a rhetorical metonym for a political “opposition party.” Ultimately our project is not designed to advocate a partisan position. Rather, we look to collect data, analyze the patterns, and make the research available to the public as a resource for their own edification.

References

Allcott, Hunt and Matthew Gentzkow (2017). “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(2): 211–36. Available at https://www.aeaweb.org/full_issue.php?doi=10.1257/jep.31.2#page=213.

Jensen, Robert (2006). “The Myth of the Neutral Professional.” Electronic Magazine of Multicultural Education 8(2). Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.523.4060&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Teixeira da Silva, Jaime A (2017). “The False Donald J. Trump Article and the Ethics of Misleading Journalism.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 68(4):1061–63.

Ward, Stephen (2004). The Invention of Journalism Ethics: The Path to Objectivity and Beyond. McGill-Queen’s University Press.