Introduction:

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is located in Manhattan, NYC. MoMA exhibits modern and contemporary art, including architecture, painting, sculpture and new art forms integrated with technology. MoMA is a world-famous museum, attracting a large number of visitors every day, which makes the process of information dissemination and acquisition particularly important. People acquire information in different ways, including taking photos, listening to commentaries, reading instructions and etc. Museums disseminate information through electronic display boards, text instructions, and broadcasting devices.

I went to the MoMA in the afternoon on March 19. In the lobby of the museum, it was not that crowded. Most people walked in twos and threes. Some of them were reading the introductions next to the sculptures, some of them were taking photos, and others were talking about the sculptures (figure 1). When I walked towards the stairs, I saw the sign on the wall which guided the visitors to the exhibition hall they wanted to visit.

Figure 1

Figure 2

After I climbed to the second floor, I saw an information desk. The lady who was sitting behind the desk gave me a map which showed the floor plans of the museum. On the desk, I noticed several different colors on the covers of the brochures (figure 2) and one color corresponded to one particular language that the brochure was written in. The brochures were a really cool design that let people from all over the world feel the warmth and respect in this museum. As I continued walking, I noticed that the free audio commentaries were a great design as well. The visitors can borrow free audio devices from the desk and use them to play the commentaries while walking in the gallery. The commentaries are translated into nine languages so that the majority of the visitors can find their preferred one (figure 3). It is so convenient for visitors that they do not need a commentator to explain the exhibits. However, mobile exhibitions only have the English version of the commentaries. The translation process now is much easier than the old times, so the museum can improve it by using artificial intelligence to translate the majority of the commentaries into different languages and refine the translations through professional editors. It will save a lot of manpower, material, and financial resources and give the visitors a better experience.

Figure 3

Then I followed the map and went to the third floor. When I arrived at the third floor, I saw an electronic screen on the wall (figure 4). Some of the visitors was looking at the screen and tried to find the collection that they wanted to see. On the third floor, it was exhibiting the furniture and decorations of the house. Visitors were watching the introduction videos which were projected on the wall. I have visited the latest exhibitions and events page from the MoMA website in advance and found Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern exhibition is on display. I went to the entrance of the exhibition hall and a lady asked me if I had the membership card because this collection was only open to members. I took out the card and she scanned the two-dimensional code on the back of the card and let me in. Compared to the traditional ways of verifying visitor information, this indeed is a new and efficient way to admit the visitors to the special exhibitions.

Figure 4

Figure 5

On the fourth floor, the art pieces were combined with technology and created a strange but special and novel feeling (figure 5). The dynamic space guided the visitors to look around and listen to the sound. The dark room, the bizarre lights and shadows accompanied by the background music let people experience the wonder and beauty of art (figure 6). I like these art items because when technology gets involved, everything becomes different and new. In Georgia Guthrie’s article “Art+Technology = New Art Forms, Not Just New Art”, she answered people’s question– “Why should we even try to use technology in art?” with this: “Because using technology in art has the potential to create entirely new art forms, and therefore new experiences for us that can be thrilling, illuminating, and just plain fun”. Technology is not only changing the pace of our lives but also shifting our appreciation of beauty in life. Technology gives us infinite possibilities to explore the beauty of the world. I am looking forward to seeing more intelligent art forms and art pieces in the future because our technology is developing rapidly day after day.

Figure 6

Finally, I got to the fifth floor where it was very crowded. The worldwide famous painting The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh was exhibited on this floor. People come to see this world-famous painting excitedly, whether or not they have an artistic background. People recorded the special moment by taking photos of the painting (figure 7). Some people did not turn off the flash, so the security guy reminded the visitors again and again. It is better to have a sign on the wall in an obvious place to remind the visitors so that the security guy does not need to remind the visitors all the time.

Figure 7

Conclusion:

I enjoyed this observation and found out how people interacted with the information in a museum. In the article Fundamental Forms of Information, Marcia J. Bates says: “Anything that human beings interact with or observe can be a source of information”. The museum is a very important place for people to experience and absorb information. Bates writes that recorded information is communicatory or memorial information preserved in a durable medium(Bates 4). The documents and photos in the museum are recorded information. People read the documents and watch the photos on display and feel the history of the exhibits that satisfies their needs for aesthetic and the desire for knowledge. The museum is a medium to communicate cultures, a force to promote social change and development, and one of our most important wealths in the world.

References:

Guthrie, Georgia. “Art + Technology = New Art Forms, Not Just New Art | Make:” Make, Maker Faire, 31 Jul. 2018,https://makezine.com/2013/11/15/art-technology-new-art-forms-not-just-new-art/.

Bates, Marcia J. “Fundamental Forms of Information.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, vol. 57, no. 8, 2006, pp. 1033–1045., doi:10.1002/asi.20369.

Xi Chen INFO 601-02 Assignment 3 Observation

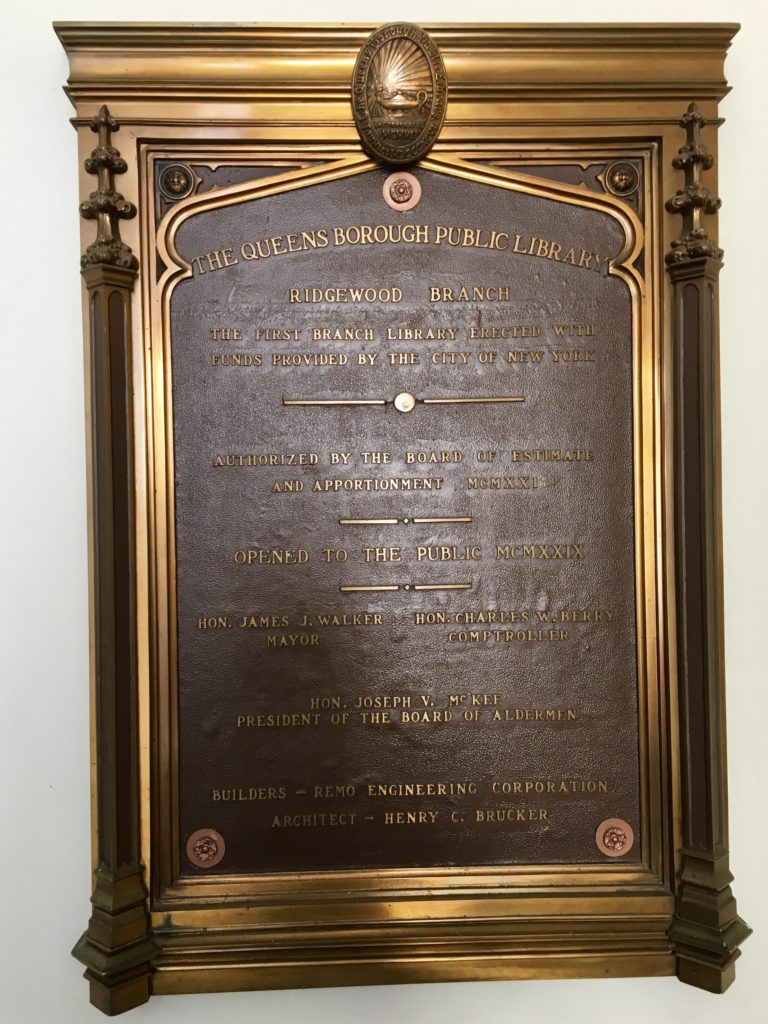

This week, I visited the Ridgewood Community Library, a branch of the Queens Library. Even though this is my neighborhood library, I had never spent time there except to pick up books I’d had transferred. The library is a fairly small branch housed in a beautiful brick building built in 1929. It was the first branch of the Queens Library to be constructed with funds from the city rather than from Andrew Carnegie. Renovated most recently in 2011, the library is fully accessible, with elevator access to every level. It is clean and well lit, with lots of natural light on the main level.

This week, I visited the Ridgewood Community Library, a branch of the Queens Library. Even though this is my neighborhood library, I had never spent time there except to pick up books I’d had transferred. The library is a fairly small branch housed in a beautiful brick building built in 1929. It was the first branch of the Queens Library to be constructed with funds from the city rather than from Andrew Carnegie. Renovated most recently in 2011, the library is fully accessible, with elevator access to every level. It is clean and well lit, with lots of natural light on the main level.