When considering the kind of information environment I wanted to observe, I wanted to observe an institution whose mission centered around engagement with and education about art objects. I chose to observe the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum as it is known as a trailblazer in the field of interactive museum experiences. I believed I would have the opportunity to observe the intersection of people, technology, and art collections in one space.

I visited the Cooper-Hewitt during a weekday morning shortly after it opened for the day. The Cooper-Hewitt is a converted mansion on the Upper East Side, situated in the middle of Manhattan’s “Museum Mile.” It is known as the Mecca of museum interactives, with touch screen and immersive digital tools featured prominently in almost every gallery space.

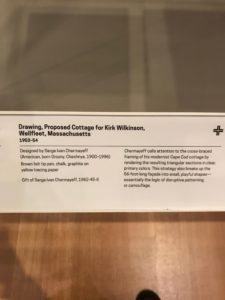

After I entered the museum, myself and a few other visitors made our way to the ticketing counter. There, we were given a demonstration of the museum’s most notable digital tool, the digital “pen.” The visitor services associate held up a sample wall label explaining if we pressed the end of the pen to a cross symbol on the label, we could save artworks we enjoyed. The works saved by the pen became a part of our own curated collection which we could access via an online code after our visit. I think this is an interesting way for the Cooper Hewitt to encourage their visitors to engage with works in the collection and continue their exploration outside of the museum. As I stepped away from the counter, I observed another visitor approach the counter to ask an associate a question. The visitor pointed to his digital pen and asked “do you give out these out so I won’t take pictures in the gallery?” The associate assured the visitor that they could still take photographs with their cellphone, but encouraged them to try the pen. They explained the pen provides clear images without the glare of the display cases, which the visitor can access at any time. The visitor did not seem entirely convinced, but made their way up to the main exhibition.

Interactive Tables: Interacting with the Web of Objects (Left) and Design Studio (Right)

As I made my way to the second floor and into the main exhibition, Saturated: the Allure and Science of Color, I noticed display cases all around the room with multiple objects inside. Near the displays and scattered around the room were table-sized touchscreen tablets. When I arrived, many visitors were hunched over the touchscreens with their pens in motion. Upon approaching the first table, I began reading the introductory text while other visitors continued to move their pens around the screen. The prompts on the table asked visitors “what will inspire you”, “what will you design,” and “be inspired.” Each screen table allowed four visitors at a time to design their own object and learn from a moving web of circles. Each orb in the web contained an object from the Cooper-Hewitt’s extensive permanent collection. From observing visitors at these tables, older patrons seemed to be apprehensive of the display oftentimes, avoiding or not approaching the screens. Younger visitors appeared very comfortable with interacting with this kind of technology and spent a majority of their visit designing their own virtual objects. Most visitors I observed did not interact with the moving web of images, instead opting for the more interactive features of the display. The touchscreen tables allowed visitors to engage with ideas from the galleries and actively design, but it seemed not many visitors were engaging with the wider collection in the way the museum was anticipating.

The Wall Label (Left) and the Pen (Right)

Observing visitors with the pen was more interesting. With the large tables, it appeared that many visitors approached the screens, because they were unfamiliar with its presence in a traditional museum gallery. Their curiosity with the technology seemed to be its main draw. Despite unfamiliarity, they had some inherent ease using the touchscreen technology, as I assume most visitors are already familiar with using a smartphone or iPad outside the museum. The digital pen was a little different as it is a piece of technology foreign to most people. and takes some effort to become comfortable with it. I observed many visitors struggling to save objects with their pens. A few visitors, frustrated with this process, let the pen dangle from the wrist-strap while they proceeded to take photos with their smartphones. It appeared patrons were either very engaged with the digital pen technology or ignored it all together. From my perspective, if a visitor was feeling apprehensive in this technologically dense environment, their interaction with the pen was the first thing to go.

In many ways, the Cooper-Hewitt functions as an information dense environment. The museum allows their patrons to engage with works on view, but also tap into their larger collection through the use of interactive technology. Given its density and foreign technologies, I found that many visitors’ “information seeking behaviors” were affected by what Elfreda Chatham defines as a sense of risk-taking. Visitors to the museum, in order to trust the information from the Cooper-Hewitt’s exhibitions, needed to trust the new technology as their connection to the information. I think the risk of not understanding how to use the pen or the touchscreen tables, made some visitors avoid the information all together.

Sources

Chatman, E. A. (1996), The impoverished life‐world of outsiders. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci., 47: 193-206. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199603)47:3<193::AID-ASI3>3.0.CO;2-T

Notebook wallpaper from Martos Gallery exhibit

Notebook wallpaper from Martos Gallery exhibit