Jewish Museum Art+Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon

Introduction

On March 3, 2019 I attended the Jewish Museum’s second Wikipedia Edit-a-thon co-presented with Art+Feminism. In celebration of Women’s History Month and the final day of the exhibition Martha Rosler: Irrespective, the event included a gallery walk-through with catalog designers Mika McGinty and Rebecca Sylvers, and assistant curator of the Jewish Museum, Shira Backer. The event was open to the public and aimed to offer an opportunity for people to learn how to edit and create Wikipedia articles in an effort to improve representation of cis and transgender women, feminism, and the arts on Wikipedia.

Martha Rosler: Irrespective

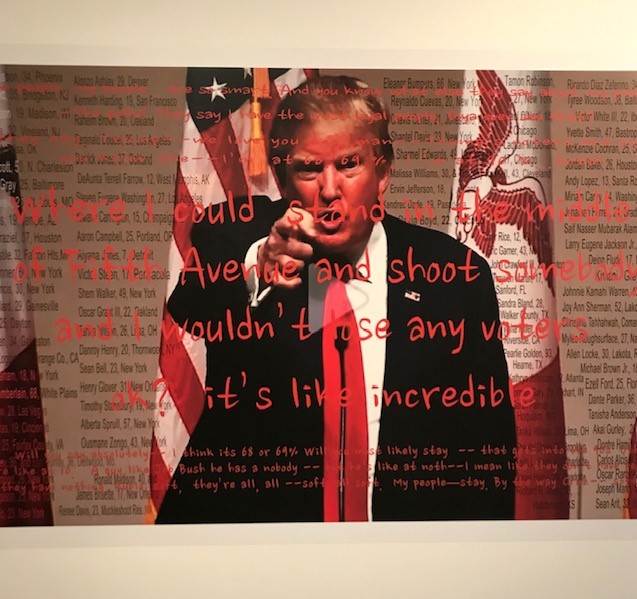

Martha Rosler: Irrespective was a survey of Martha Rosler’s work over her five decade-long career. Rosler’s work is dynamic and continually evolves and reacts to the social and political issues of today, yesterday, and tomorrow. Her work largely addresses matters related to war, gender roles, and urban gentrification, and throughout her commentaries runs a reflection on feminism that doesn’t shy away from the feminine. As a result, it would be hard to categorize Rosler’s work according to any one theme. People often describe Rosler’s work as “deeply political”, “feminist”, “intentional”, “outward”, and “intersectional”. Rosler fondly describes her own work as “hamfisted”.

The event kicked off with a walkthrough of the gallery led by Shira Backer, Mika McGinty and Rebecca Sylvers. The three designers gave unique insight into the processes of exhibit curation and art book formation – where they meet and where they diverge. They stressed that the book and the exhibition were not made to be one-to-one; they could emphasize different projects due to the constraints or capabilities of the two methods. In other words, the book was an opportunity to cover pieces not highlighted in the exhibition and vice-versa.

The exhibit tried to convey Rosler’s dynamism. There was a fully set dinner table with a voice-over of a woman discussing domesticity and the expectations of French women; a selection of five videos that examine the representation of women in pop culture and American imperialism; a large prosthetic leg swinging from the ceiling to a jaunty rendition of “God Bless America”.

It is interesting to consider the challenges in showcasing and preserving dynamic and ephemeral art like Rosler’s. Rosler continually changes and adds to her work, often including participatory elements to her pieces and installations. As a result, some questions the designers had to consider include: Is the first iteration the most important?; Is repetition valuable?; Does chronology take precedence? But no matter how hard someone tries to accurately preserve some creation, there is no absolute concept such as ‘permanence’. As Cloonan proposes, “the paradox of preservation is that it is impossible to keep things the same forever. To conserve, preserve, or restore is to alter” (Cloonan, 2001). For that matter, it seems to be Rosler’s intention to create ‘mortal’ work. Work that shifts, changes, and ultimately dies. It allows us to question preservation, even our own mortality.

The curators were evidently aware of their role as history-makers and story-tellers. They cautiously discussed Rosler’s work on her behalf, careful to distinguish between their own interpretations and Rosler’s intentions. In addition, the curators revealed that they frequently worked directly with Rosler. It is important to note that they worked with a contemporary artist who was able to be active in her own storytelling. However, regardless of their efforts, the curators ultimately could only tell a single story of Rosler – their own version – and not Rosler’s whole story.

Wikipedia Edit-a-thon

After the exhibition there was a Wikipedia training course led by Carlos Acevedo, Digital Asset Manager of the Jewish Museum, followed by an open-editing session. The goals of the edit-a-thon were for beginners to learn how to edit on Wikipedia, to improve citations of women artists, and to expand biographies of women artists on Wikipedia (Acevedo, 2019). No prior editing experience was necessary in order to participate in the event. The museum also provided a number of laptops for guests to use. For an event that aimed to increase editing accessibility and improve women’s presence on Wikipedia, providing laptops and promoting a “welcoming spirit” was significant.

The Wikipedia edit-training considered the power and responsibilities that editors have. For example, it was emphasized that articles should be written from a neutral point of view. This is arguably impossible. However, the effort to avoid overly opinionated articles and original thought in edits is a fair endeavor considering the point of a system like Wikipedia is to collect and share existing knowledge as accurately as possible.

Event Stats

- 25 people attended

- 2 complete articles created

- 36 articles edited

- 145 total edits made

Representation & Closing the Gender-Gap on Wikipedia

Gender bias on Wikipedia is not limited to the underrepresentation of women and nonbinary people on the site, but is also reflected in the fact that a vast majority of editors are cis-male. For that matter, the edit-a-thon was not only an effort to improve coverage of women on Wikipedia, but also an effort to help close the gap in contributions made by women. According to Art+Feminism, a Wikimedia survey showed that less than 10% of Wikipedia’s editors identify as cis or trans women. Moreover, editors who identify as women are far more likely than men to have their edits reverted (Acevedo, 2019). Therefore, encouraging women to participate in editing projects and creating more opportunities to do so are important efforts that may help improve coverage of cis and trans women on Wikipedia.

In Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory, Schwartz and Cook describe the power of archives to shape and direct historical scholarship and our collective memory. They beg archivists to consider the power they have to essentially write history, to privilege and to marginalize. These concepts of power and privilege are not specific to archivists. This power is shared by all who document, curate, store, and share information. The curators of Martha Rosler: Irrespective were aware of this power and therefore worked to acknowledge it. Correspondingly, the Wikipedia training course clearly considered the power held by editors and the source itself.

Just as history has been written in favor of the patriarchy at the expense of women, future of representation of women and other marginalized members of society lies in reclaiming power over the documentary record and the institutions that share information. By recognizing the inherent power in archives, museums, Wikipedia, and other memory-institutions, and using that power to tell and support each other’s stories, cis and trans women can hopefully close the gap in gender representation. As an open access and open source, Wikipedia may be the place to start – the power is literally in our hands.

By Tina Chesterman

References:

Acevedo, C. (2019). Jewish Museum Wikipedia Edit-a-thon co-presented with Art + Feminism. [PowerPoint Slides]. Retrieved from: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1F6s9logWLiRTrX9l5Tt9E4GW2VTauLbhSRZBgRQj8QE/edit#slide=id.g51b9607e8b_0_122.

Cloonan M.V. (2001). W(H)ITHER Preservation? The Library Quarterly, Vol 71, No. 2.

Schwartz, J.M. & Cook, T. (2002). Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory. Archival Science 2.