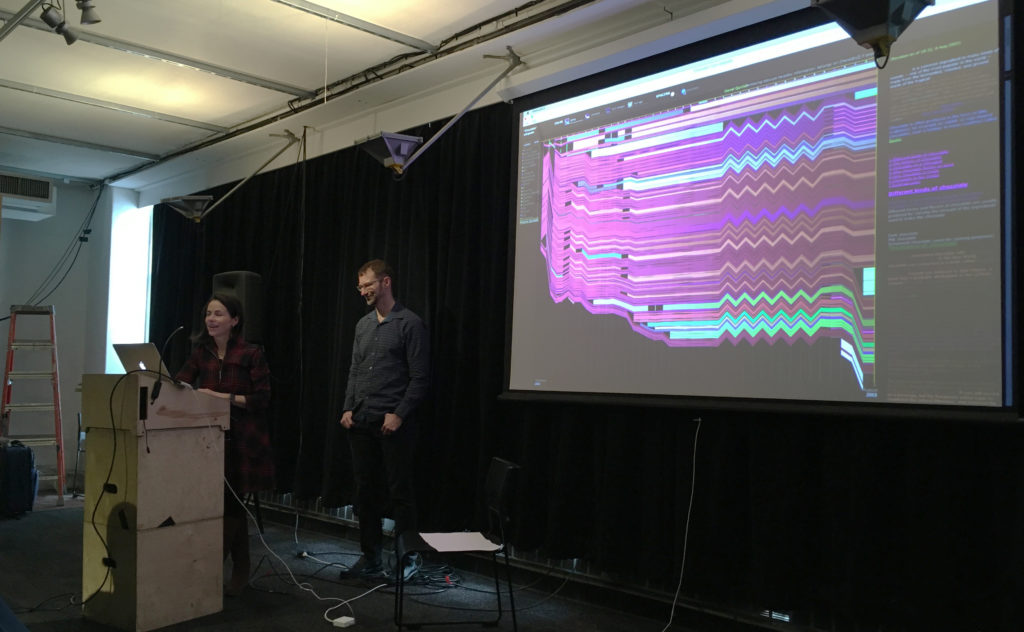

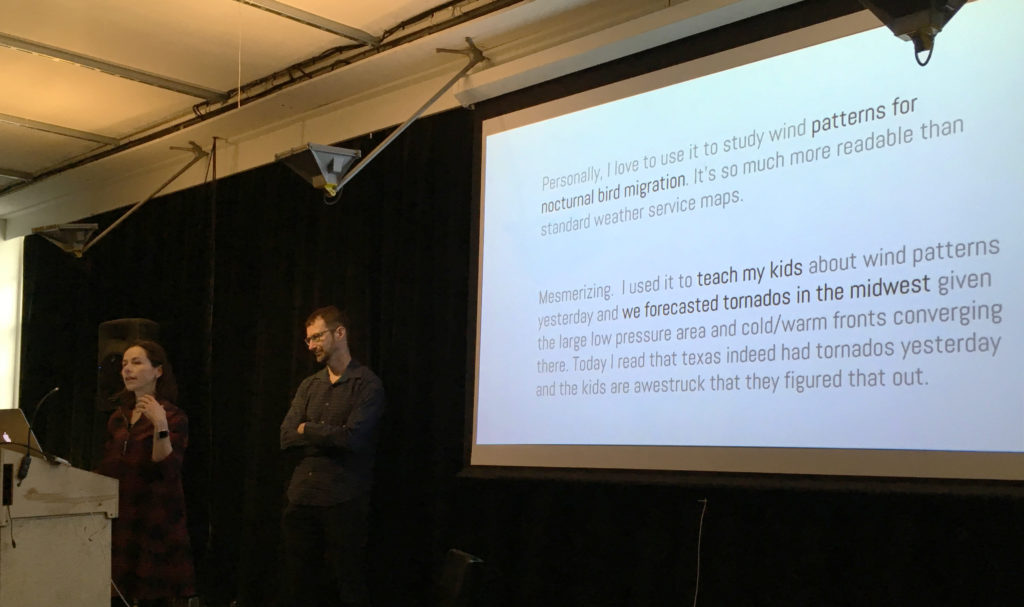

I attended an event at the NEWLAB called Data Through Design, which was split in three separate sections, an exhibit viewing, artists discussion, and panel discussion. This event was an independently organized exhibition for data and cartography where they introduced a few artists who have used data in their projects and a panel discussion based on proxies was discussed. I’ve participated in the entire event and gained a lot of knowledge from the events discussion based on what the artists and panelists said throughout the event. This event was a high interest to me because I wanted to gain much more understanding in data collection from online data websites and how it can be used for a design project. I have taken a data visualization course in programming on my undergraduate years and have knowledge in collecting data but I wanted to learn more. Back when I took my data visualization course, I was very amazed in how data sets can be used in a program to determine a solution and get information. Even though I have knowledge in data collection this event caught most of my attention because of its panelist discussion in everything is a proxy. The panel was a discussion about proxies in data models where they are used in the complexity of getting a specific data set that works best for your project or needs. Proxies is everything is their theme in the discussion and this is because proxies are the information of things around us that can be brought together in order to be used in special work for the society. In my understanding the event is teaching the audience to grasp knowledge on data and how data is useful to the people and their works.

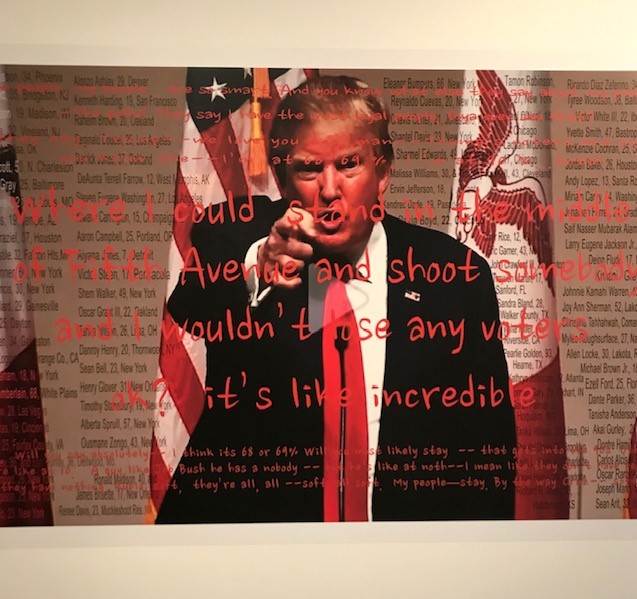

At the event I saw an exhibition viewing. In the exhibition there were a couple of projects created by the artists who were in speaking at the event. There was piece of works called temporal views of a bike lane, collision course, cards against hate, and a few more. All of these exhibits have data collection in them that was used to be created. For example, one of the exhibits called cards against hate showed cards that had different information about none hate crime in the week based on religion, race, and other subjects. The artists who created these cards used a data collection to get the information they needed to showcase their work. The artists who created this piece of work spoke to the audience and said that the data sets they used helped them get what they wanted and they agreed that the data collection of information would change the society in many ways.

The event talked about how useful data is helpful to the people and the design projects that are being developed by artists. Data is a big informational source that never ends. You can use data for anything you want. But mostly people use it to find solutions, make life simple for its users, and create a better living for the society. The information within data is very big and you can find about anything on the topic you choose to explore on. I believe that the information within data is useful in many ways and will help the people or users interact with products that use data in a much effective way. There is still a lot more information to be added to data. It is a growing branch that has no limits. Data is big and is growing more and more every day.

Proxies or data collection is a good tool because it helps users connect with information in a faster and smarter way. As Jim Martin and Raik Zaghloul say,

Collection management is profoundly affected by rapid changes in the library profession. While this provides librarians with opportunities to connect users with information, it also demands the ongoing development of new skills (Martin & Zaghloul, p. 313).

Even though I have knowledge in data collection, I have learned a lot by going to this event. This event should go on more throughout the years as technology is developing every day. The event has given me the understanding of how data or proxies is a big solution to the society. I believe that the event changed the way I see data in the way that data not only has been used at libraries, programs, but also on design works like cards against hate. Many of the words spoken about data at the event gave me the expertise on how data collection is used in about almost everything that we can think of.

Reference

Jim, M. and Raik, Z. (2011). Planning for the acquisition of information recourses management core competencies. New Library World, 112(7/8), 313-320. Retrieved from URL https:// doi.org/10.1108/03074801111150440

Link to event: http://2019.datathroughdesign.com/