Category: Sula

Chinese Language in the Era of Information

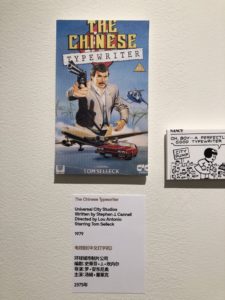

“Chinese characters are innocent,” said MIT-educated Chinese scholar Zhou Houkun in 1915 and quoted by the curators at the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) as a radical introduction to an exhibition titled Radical Machines: Chinese in the Information Age. Set in the special exhibitions gallery, the exhibition is curated by Dr. Tom Mullaney from Stanford University. Exhibition materials range from archival documents, books, video clips, photographs, and the most eye-catching, rarely-seen vintage Chinese typewriters. Most of the items belong to Mullaney’s personal collection, which is “the largest Chinese and Pan-Asian typewriter and information and technology collection in the world” (mocanyc.org). This collection was formed along with the development of Mullaney’s years of scholarship at the intersection of East Asian history, history of science and technology, and transnational/international affairs.

The radicalness, nurtured within the complex machines themselves, also sits in the nature of the Chinese language, together with many other languages from the East, being non alphabetical and thus having faced and still facing constraints in having a smooth merge with modern information technologies particularly on the end of inputting. This curatorial project as well as Mullaney’s research thus aim to be a unique introduction to this less known piece of history and a provocation to the Western dominance structured around information technologies.

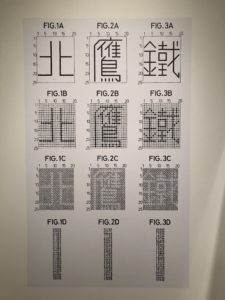

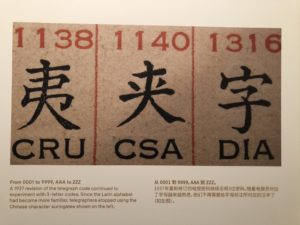

The exhibition was divided into multiple sections, drawing curious visitors first into an brief overview of the Chinese language, characters and phonetics, and the early history of printing press — Movable Type. Departing from there, since the base of written Chinese involves largely pictograph, morphing the characters into something more systematic emerged as one approach to “alphabetize” Chinese (see photo). On the other hand, the section titled Chinese Telegraphy introduces a second approach of assigning a combination of Latin letters to each of the commonly used characters. Traced back to 1870s, this method seems to be the starting point when the Chinese language was equated to English in order to adhere to the development of information technology and people’s communication needs.

Evolution of technology and shifting mode of communication have been increasingly intertwined. To answer the question of how communication defines social existence and shapes human development, exploring the history of communication technologies, from speech and language, writing, to printing press, gives us a developmental model to discuss Internet, as the agreed fourth one (McChesney, 69). The exhibition pretty much follows this itinerary when it takes visitors to explore the following two sections: Beyond QWERTY, The Typist in China.

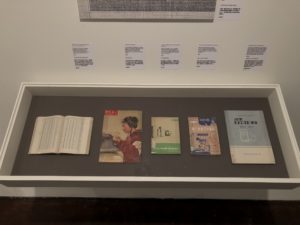

Beyond QWERTY exhibits several systems developed in history for inputting Chinese language, from the common word usage system, to later developed Wubi system, namely entering stroke-by-stroke. The section illustrates how information technology involves a large degree of customization due to the varying linguistic composition of languages. Therefore, learning how to type on a QWERTY keyboard becomes a less intuitive task for Chinese speakers. The Typist in China introduces the cultural history of learning to type using different methods, stroke-by-stroke Wubi or the phonetic method Pinyin. Echoing pieces of Western history, learning how to type, from textbooks and illustrations, became an appreciated skill for various professions. This is also very reminiscent for me as growing up in China, we also spent a good amount of time learning how to type and recently there’s also a discussion around that since Pinyin is easier to learn and few people can now use the Wubi method to type.

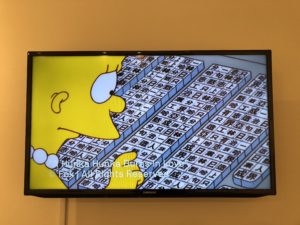

Personally a highlight of this exhibition turned out to be a section in the back of the gallery, named Western Perceptions. Absolutely less discussed, this section, including historical Western views of Chinese information technology presented in the realm of media and entertainment, attends to the issue from a cultural perspective. One will find video clips of Lisa Simpson and James Bond perplexed by a Chinese keyboard, Nancy in the cartoon puzzled by a Chinese typewriter found in the city dump. These manifestations carry a strong racist overtone, mocking the Chinese language being non-systematic, irrational, and thus not modern enough to keep up with modern technology.

Obviously there’s issues around class and accessibility, but most often we perceive technology to be culturally neutral, or that technology even being a way to culturally collectivize human beings. Yet, Radical Machines tells us that technologies could also be racialized and the prejudice reflects what has been projected onto its users. Though framed under the umbrella ideas of language, information, and technology, the curators also sought to integrate “difficult heritage” — “pasts that are meaningful in the present but that are also contested and awkward for public reconciliation with a positive self-affirming contemporary identity” (MacDonald, 6) — into this exhibition. MacDonald in her research discusses that the task of tackling difficult heritage is indeed hard for museum and heritage institutions, in that on the one hand, museums, as public educational institutions with a sound voice, must take on the responsibility in addressing difficulty heritage, and gladly according to research observation, an increasing number of institutions are willing to do so (MacDonald, 16). On the other hand, how to address difficult heritage in a provoking yet equally inviting way always needs extensive discussion. MOCA has been an active participant in exhibiting difficult heritage: narratives in this particular section of Radical Machines resonate with those in the permanent exhibition next door, “Within a Single Step: Stories in the Making of America.”

Continuing with the socio-cultural perspective, the curator took this aspect to mark an end of this exhibition — “China is the world’s largest IT market? Isn’t it the time we knew it’s history?” Linking the past to present, Radical Machines: Chinese in the Information Age successfully raises the dialogue on information, language, and technology with a unique lens. To learn more on this topic, Dr. Tom Mullaney’s blog, though not updated in a while, has a handful of interesting articles.

Bibliography

MacDonald S. (2015). Is “difficult heritage” still difficult?. Museum International, 67, 6-22.

McChesney, R. W. (2013). How can the political economy of communication help us understand the Internet? In Digital disconnect: How capitalism is turning the Internet against democracy. New York: The New Press.

Museum of Chinese in America. (2018). Radical machines: Chinese in the information age. Retrieved from http://www.mocanyc.org/exhibitions/radical_machines

Protected: The Office: an Observation at Compass

Event: National Design Award 2018 Winner’s Salon- Humen Experience/Built Environment

The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum is my all time favorite, not just because of the well-curated collections or exhibitions, but the great museum experience design impresses me as well. When I searched online for events, the Cooper Hewitt Museum popped up in my head and that’s how I found this salon event as part of the National Design Award Week 2018. The 2018 National Design Award aims to honor excellent and innovative American design, and also seeks to raise awareness of the impact of design in the education sector (“National Design Award”, 2018). National Design Awards 2018 included a bunch of activities, such as workshops led by Award-winning designers, exhibitions, panel talks, and salon events. Because of my landscape architecture design background and my interest in designing for human beings, I chose to attend the “Human Experience/Built Environment” salon.

BRIEF INTRO OF HUMAN EXPERIENCE/BUILT ENVIRONMENT SALON

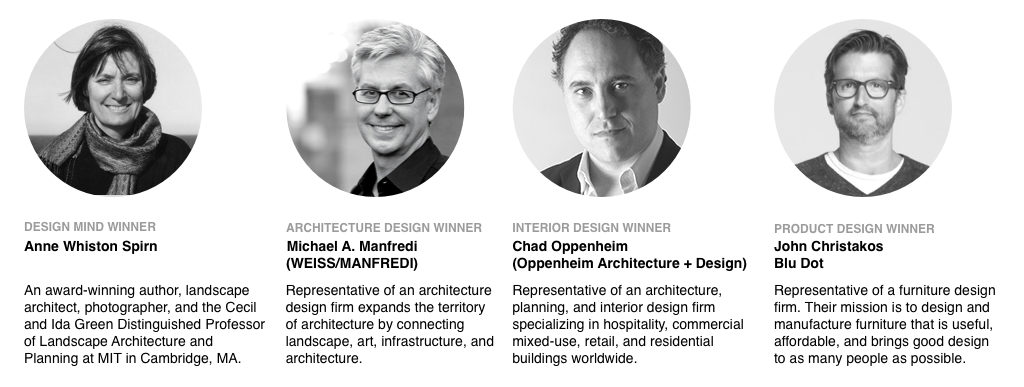

This event invited four National Design Award winners to share their creative /collaborative process for designing human experiences, challenges while designing, and the relationships between the built environment and designers (“2018 National Design Awards | Winners’ Salon & Master Classes”, 2018). Four award-winning teams/individuals are from different backgrounds. It’s a combination of a creative author, a furniture designer, an architect and an interior designer.

CREATIVE PROCESS

The salon started with inviting winners to share the creative process of their design works. Anne Whiston Spirn shared her process from an author perspective as the starting point. She is a person who would always start with an observation through her own eyes or the frame in the camera. She believes observation could reveal many things that you might ignore in your day-to-day life, for example, a buried river in the city or any other invisible forces that support human’s life. By doing so, observation can actually uncover the truth and yell us more about how life is lived. She will also talk to locals while observing in order to get the overall picture as a whole context. Michael Manfredi, the architect who represents WEISS/MANFREDI, added that his way of doing environmental design by talking to the local communities before even starts to sketch anything. When starting a new project, he would always keep “humanity” in mind, and reminds himself to be a person that knows nothing but eager to learn from and interact with communities. Chad Oppenheim from Oppenheim Architecture + Design tends to initiate the process from a childlike perspective. He goes to the site, wanders around and explores the environment like a boy back in the time when there was no Xbox and Gameboy. This approach helps him to discover the relationship between nature and humans, so he can really design for human experiences. Lastly, unlike other designers in this talk, as a furniture designer, John Christakos, the product designer of Blu Dot, oftentimes discusses with his partners about what piece of furniture they should design in the very beginning. Then they will sketch as a team to iterate the design work until the design goes to prototyping. That’s the reason why they never mark any of the design pieces as an individual work.

CHALLENGES AND COLLABORATION PROCESS

Manfredi mentioned how climate change impacts his consideration of spatial design as an architect. In the past, architects or urban planners didn’t really have to consider how to deal with the life-threatening storms, except in a waterfront neighborhood. But now, it has become a baseline requirement when designing spaces. He also shared how he collaborated with local dog owner communities in order to design a great dog park. His team facilitated a conversation of the local dog community, so each dog owner group could voice their opinion, and exchange their thoughts at the same time. After the conversation, the team sketched the park based on the discussion, then presented to the groups in order to receive valuable feedback. When the park was built and finally open to the public, the dog community was really satisfied with the outcome.

REFLECTION

1. Collaborating with communities is the key to designing good human experiences.

In my opinion, the spatial design discipline might be the pioneer of “user experience design.” For instance, when I studied landscape architecture design in college, to go on a field trip for observation already became a “must-have” process when designing a space. The purpose of going on a field trip is to understand the relationship between space/environment and the people. During the trip, designers are required to get to know about the local community as much as possible. Designers can either talk to local people directly, live with them for a few days, or just participate in local events. These methods will enable designers to discover the problems affecting an area, then explore the opportunity for solutions. Thus, it’s pretty common for architects/landscape architects to interact with communities and this “interaction” has even become part of the key process of spatial design.

Outside of the spatial design field, I feel designers tend not to have many interactions with communities (no matter if it’s a geographical community like a neighborhood, or a group of people that share something in common like small dog lovers). For example, when I worked as a UX designer, I did interact with “users” or “target audiences”, but the scale was smaller and it was more l goal-driven (wanted to know their devices usage patterns ), or task-driven (tested usability before releasing a new feature) approach.

So when Sasha Costanza-Chock wants designers to rethink the design processes in her article” Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice”, that recalled my memory as a landscape architecture design student instantly. In her article, she encourages designers to address the challenges of communities by applying collaborative, creative methods as part of the design process, and to be a “people first” designer (Costanza-Chock 2).

When one of the winners, Whiston Spirn, works on her projects in West Philadelphia, she collaborates with locals by treating locals as experts based on their lived experiences. Her team focuses on building a sustainable, community-led living environment by inviting locals to share their knowledge and teaching them about landscape literacy. In her design process, designers are more like facilitators than experts. The other winner Manfredi, invites people who will be impacted directly in the future to join the design discussion. He wants to create an environment in which designed is based on the prioritized impacts for the community. These methods actually match the framework mentioned by Costanza-Chock in the Design Justice article. No wonder the final design outcomes were engaging and resident friendly, and even won the prizes.

2.Lack of diversity in design industry

When I first saw the winners in front of the audience, I was a bit disappointed. Three of the four winners are male, and there were no people of color except white people, nor people with disabilities. I thought the topic is about designing human experiences in America, a place that is full of diverse cultures, languages, and people, which should lead the topic to accommodate various needs and situations that are more inclusive. This fact reminds me of Jennifer Vinopal’s article about diversity in library staffing (“The Quest for Diversity in Library Staffing” 2016). She brought up the issue about “lacking in diversity based on race and ethnicity, age, disability, educational background, gender identity, sexual orientation, and other demographic differences” (“The Quest for Diversity in Library Staffing” 2016). Vinopal’s finding could actually apply to almost all work fields, including design disciplines. Her intention to raise the awareness of lack of diversity in the workplace aims to combat “the oppression that is caused by privilege, bias, and the attendant power differentials at no matter individual or systematic levels” (“The Quest for Diversity in Library Staffing” 2016).

Incorporating every possible role to every work field seems a bit impossible for now, and I am not sure if this is a good approach to solve the problem. When we discussed difficult heritage a few weeks ago, I defended Maya Lin’s design of Vietnam Veterans Memorial by stating “designers don’t necessarily have to be part of the group they design for”, because she was being accused as an unqualified designer due to her role as an “outsider” (meaning that there is no Vietnam veterans in her family). In this case, because the objective is controversial, the interpretation of the memorial is always different for each individual, and it’s hard to find a Vietnam veteran who has the skillset, and also who is not suffering from Post-traumatic stress disorder to design this monument. Therefore I don’t think this approach works here. However, there should be a better way to address the lack of diversity issue in every work field. Costanza-Chock already initiated the solution by applying a doable design framework to improve not only the design process but also the final outcome of the design. Whiston Spirn does co-work with the communities for over decades and the result is amazingly impactful in a good way. There would definitely be more good solutions to accommodate this issue.

This event raises my awareness of two topics: design justice and work field diversity. Some of the practitioners in design disciplines already integrate similar methods into their work process to make the design more welcoming and accomondable in most situations. We should make this notion more wide spread through to different disciplines to make this change happen.

RELATED SOURCES:

- “2018 National Design Award – About The Awards.” Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 31 Oct. 2018, https://www.cooperhewitt.org/national-design-awards/

- “2018 National Design Award Winners.” Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 31 Oct. 2018, https://www.cooperhewitt.org/national-design-awards/2018-national-design-awards-winners/

- COSTANZA-CHOCK, Sasha.“Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice.” Design Research Society 2018 Catalyst, 25th-28th, June, 2018

- Vinopal, Jennifer.”The Quest for Diversity in Library Staffing.” In The Library With The Lead Pipe, 2016, http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2016/quest-for-diversity/

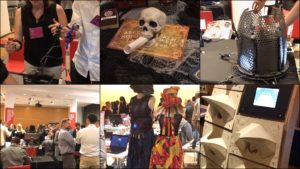

ARMA @Noon /October 18th

An ARMA Metro NYC conference names ARMA @Noon was held in NYC on October 18th.

Introduction:

ARMA invited Richard R. Gomes, a Corporate Culture and Engagement Strategist who works for Citi Group to present some concept of corporate archives as a business setting. The conference room located in Kelley Drye and Warren, 101 Park Avenue. There are around 20 people join the event – almost half male and half female. The rough estimate of the age range is from 25 to 80. Food and beverage provided in the side of the room, eating is allowed during the meeting. Also, they said the day is the first day they try to broadcast the conference to the members with a webcam at the front of the conference room. The conference started with a relaxing atmosphere, Ricard and the chair of ARMA briefly introduced themselves then asked everyone to do so.

Most of the participants are professional archivers, while Richard himself isn’t. He called himself a businessman instead of an archiver. He also mentioned he had no archive profession. I introduced myself as a graduate student who interested in the event and encouraged by my professor. One good thing is, ARMA kindly welcomes students and washed away my worry of attending a professional conference as an inexperienced novice.

Record:

The whole content of the conference focus on how to make longevity a competitive advantage. While “trust” is the most important element of banking, the value of archives could be significant. Historical archives of a business group are literally the proof of its stability and security. Better than propaganda, fact telling is all true. Richard illustrated the concept with an experience of expanding Citi’s business to Asian countries – mainly Japan. At the time, Citi group was actively expanding branches and franchises of overseas markets.

Deposit money at one place and withdraw money at the other side of the world was still an innovative concept decades before. They had encountered regulation and document problems when trying to get permission to found their business. Citi Group got through the obstacles by showing the government that they had a lot of experience dealing with various problems. The proves are convincing. He also mentioned that not only “good history” could be beneficial.

“Do you know we are blamed for Great Depression?” He asked. The uses of archives are not limited to keep tracks of the activities. Archives could show how the group went through and recover after difficult situations. Failure taught lessons, and Citi has learned from it. Sometimes the events themselves are not the ones weighing the most, it’s the flow of it, just like the core of programming codes is usually the logic but methods. These archives could also help analysts model the data and anticipate with the models. That is, another facet of difficult heritage: Teaching groups relevant to the history there is meaning over miserable memories.

The technique of storytelling is indeed important while turning heritage into business. We were passing a beautiful book and a box of well-designed paper cards with photo and text around the conference room. All of the products we saw were charming and informative. In addition to publishing brochures and the other paper products, Citi Group created some activate spaces for clients and other business uses. Richard said that is a good way to show the history of the group by sitting inside the history and talk about the future.

Instead of trust from the clients and governments, the archives are also benefitting the recruiting. There are thousands of talented freshmen every year. Just as the clients, they are also eager to know “Why Citi?” when there are over hundreds of different choices for their career. Sometimes understanding creates value. By telling the story, the group is able to attract talented new employees sharing the same memory (of the organization) and probably the same belief. Another benefit of building and preserving these archives is, some employees might want to be remembered. (“I don’t. “Richard joked.) With recognition and sense of belonging, they might work harder in the purpose to become a name carves on the group history.

As M. Schwartz and Terry Cook claimed:” Archives – as records – wield power over the shape and direction of historical scholarship, collective memory, and national identity, over how we know ourselves as individuals, groups, and societies.”[1] These modern memories have strong power within our identity. Except for common “interface” like museums, art galleries, libraries, historical monuments, the places Citi Group build for their clients and employees are somehow ignored in most of the academic articles.

Related experience:

The history of Citi Group reminded me in my college time our class was able to interview a manager from Mitsubishi Group, a Japanese business group which has experienced the history of “Black Ship” (The history that America use military power to “negotiate” a treaty allowing American trade with Japan.) They had kept a lot of precious and unique information. How they raised, how they traded. How people made money. I suppose with the enter of capitalist society, more and more historical footprints would be located in private cooperation but governmental record.

Conclusions:

At the end of the conference, Richard said that people should value data and archives just like valuing other resources. Longevity is resource, and it could create more resources. Knowing the importance of archives, he gave out three principles of business: Being investing, being effective and could be easily documented. Not like official files, specific collections usually don’t suffer cataloging problems like queer theories. The way people manage archives is more convenient than the official way. While they hold some control of their own event records and documents, more archives seem to be born in the way easier for archivers to deal with.

Even though Ricard doesn’t see himself as an archiver, he preserves the archives, makes use the archives and knowing the value of the archives. I would say Richard is more than an archiver but also a businessman. I was able to ask a question about one project of Citi Group – Citi Bike. There are similar things in my city. Our city government put them on the street to encourage people moving around. Richard kindly answered my question. I was so agreed with the things he said. It is important to let people know about the possibility of different choices. Whether it is shopping choice, a wider range of living area or knowledge access. The archive is the base of these possibilities.

[1] Schwartz & Cook, (2002), “Archives, records, and power: the making of modern memory”

Protected: Trial by Fire: User Testing and Experience at the Morgan Library and Museum

Meetup: Designing Technology for Older Adults

In September, I attended my first Meetup – ‘Designing Technology for Older Adults.’ The speaker was Yasmin Felberbaum, a Ph.D. student at the University of Haifa. The focus of the talk was threefold: (1) the challenges of designing for older adults; (2) the design decisions that could improve products for these users; and (3) examples of well and poorly-designed products aimed at older adults. For this article, I will use Felberbaum’s research to show how these design considerations tie into our readings about user-centered design, design justice and the political economy of information. First, I will highlight the design challenges associated with older adults, and how these are undergoing a transformation. Next, I will discuss what inclusive design means in the context of Chock’s ‘Design Justice.’ Finally, I will use Felberbaum’s research to show how we can best design for an elderly population, reflecting principles championed by the Design Justice movement.

Design challenges for older adults

The event began by defining an ‘older adult’ as anyone over the age of 65 and highlighting the challenges associated with designing for this segment of the population. These fall into three main categories:

- Physical – motor changes, e.g., inability to hold a device for an extended time;

- Mental – cognitive and emotional changes, e.g., loss of loved ones may cause depression or decreased motivation;

- Educational – low levels of technology training and skills are still prevalent.

Due to population increases and improved life expectancy, estimates currently put the number of adults aged 65+ at roughly 2 billion by 2050, according to Felberbaum. However, the older adults of today are vastly different from those of the future, a point which Norman references in his ‘Being Analog’ article. As our everyday lives are becoming increasingly complex, ‘the slow evolutionary pace of life is no longer up to the scale and pace of technological change’; meaning that humans must now try to keep up with ever-increasing and oppressive amounts of knowledge. As a result, the current generation of young, digital native adults, are being shaped by different experiences with technology. They have higher expectations for technology to help them cope with so much information. The way that young adults today interact with technology is also fundamentally different. According to Benkler’s ‘The Wealth of Networks,’ our interaction with technology today is much more pervasive than it was 50 years ago. The conclusion we can draw from this is that to disregard older adults as an insignificant portion of technology consumers is seriously misguided. Not only will they become increasingly significant in size and purchasing power, but they will also be more demanding in the quality of that technology and how it serves their lives. They will be healthier and better technically educated and will fully expect to be included and designed for, much as they would have been when younger.

‘Design Justice’ as a way to overcome exclusive design processes

One of the main arguments presented by Felberbaum was that stereotypes about technology products for older adults, e.g., low adoption rates, are often a result of the exclusion of the user group from the design process. This omittance is just one example of designers overlooking users who do not conform to the stereotypical ‘imagined user […]. In the U.S., this means straight white middle-class, cisgender men, with educational privilege and high technological literacy, citizenship, native English speakers’ and, I would also add, young age. Constanza-Chock discusses recent attempts to overcome this in her Design Justice article. Design Justice champions a set of principles that, when included in the design process, should fairly and accurately represent marginalized users. It recognizes that the participation of these end users in the design process is crucial to creating products that are valuable for them. This is relevant to Felberbaum’s presentation, as she gathered her insights through the direct participation of older adults in her research process. She conducted in-depth interviews with her users, who were questioned and observed while using technology products with both inclusive and universal designs. The feedback gathered included which products users were more likely to adopt and why, what product issues they could not overlook and what they found attractive or helpful. Here is a clear example of Design Justice at work: the inclusion of the participants and recipients of the design as key contributors.

Constanza-Chock also presents the idea that designers with diverse backgrounds and experiences, especially those from marginalized communities, could help broaden perceptions of the ‘imagined user,’ resulting in fewer overlooked groups. While this is a worthy goal that should be encouraged, it may prove difficult when considering an elderly population. One of the very reasons that old adult marginalization occurs in design is because they are physically or mentally unable to participate in the process, or are retired from the workforce. Therefore, advocating that adults over 65 become designers to mitigate their exclusion may not be feasible. In these cases, applying concepts of user-centered and empathy-driven design become even more critical. These can help to supplement knowledge and experience gaps when designing for users that cannot fully participate in a process that was created precisely for their inclusion.

Best practice design for older adults

The final part of the event focused on the insights Felberbaum gathered from her research with older adults. These can be summed up as:

- The social or gamification component of a product was vital to secure adoption and continued use;

- Adoption only happens where there is a clear added value, e.g., what am I gaining by using this, that justifies introducing a new habit at a late stage of life;

- The design should be universal and not inclusive – older adults did not want to use products aimed specifically at them due to stigma or emotions in acknowledging a perceived diminished place in society;

- The lower the interaction and learnability requirement to use the product or device, the higher the adoption rate;

- Where new information is necessary to use the product, this must build on existing or prior knowledge to secure adoption;

These insights provide good examples of best practice when designing for adults over 65, and they were all elicited by communicating with the target user group. These insights also touch on one of the action’s outlined in Gehner’s article, specifically: ‘understand that charity is not dignity; dignity is inclusion.’ I think this is particularly poignant and applicable to the outcomes of Felberbaum’s research as the products that had the most success were those that did not treat older adults as a separate segment of the population that needed unique designs. The older adults interviewed wanted to feel included, empowered and just like everyone else by being able to use the same products as their children and grandchildren – universal design was overwhelmingly the preferred choice.

Conclusion

The event made me think critically about my relationship with technology as a future older adult. It was also significant, as an aspiring UX designer, to see an example of design justice at work providing higher quality insights. Often, as Norman points out, what we attribute as issues with users, are a result of poorly designed products. Stereotypes, such as low adoption rates among older adults, are dangerous because they similarly focus the problem on the user and not the product, making designers less inclined to change their design process. The key takeaway for me was that it doesn’t matter what user segment you are designing for – if a user-centered approach is used, adoption will occur.

Works cited:

- Costanza-Chock, S (2018). Design Justice: towards an intersectional feminist framework for design theory and practice, Design Research Society 2018.

- Norman, D. A. (1998). The Invisible Computer: Why Good Products Can Fail, the Personal Computer is So Complex, and Information Appliances are the Solution. MIT Press. Chapter 7: Being Analog.

- Benkler, Y. (2006). “Introduction: a moment of opportunity and challenge” in The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. Yale University Press, 1–18.

- Gehner, J. (2010). Libraries, Low-Income People, and Social Exclusion, Public Library Quarterly, 29:1, 39-47.

Understanding media and technology | NYCML’18

What is NYC Media Lab’18

Every year, NYC Media Lab hosts a summit where investors, professionals and students come together to present projects and ideas. This year’s NYC Media Lab Annual Summit was held at The New School on September 20th. There were thought-provoking debates, hands-on workshops and 100 demos. Attendees appeared thrilled to explore the future of digital media innovation.

Keynote speakers

Keynote speakers were Thomas Reardon, CEO and CO-Founder of CTRL-Labs, and Maya Wiley, Senior Vice President for Social Justice and Co-director, Digital Equity Lab The New School.

Reardon’s talk was the highlight of the event. It was very engaging and insightful. Reardon has received his PhD in Neuroscience from Columbia University. The core idea of his discussion was very similar to what Don Norman said in his book “The Invisible Computer”. Norman discusses what computers are good at and what humans are good at. He then suggests that technology is designed and people are being asked to conform to the needs of the computer. Although it is useful to take advantage of the strengths of the computer, this only works if the machine adapts itself to human requirements. Reardon presented a technological solution to issue Norman discussed in his book. He discussed the huge gap between human input and human output. How neural interfaces can solve the output delay problems. He explained that muscles are causing delays in the output, and if we manage to read the mind, we can eliminate muscles from the process. He argued that capturing intention, not just motion and making it work, is the future. He also mentioned that this technology will help people with motor neuron diseases. After hearing his ideas, I am very excited to learn more about neural control and robotics.

Wiley is a nationally renowned expert on racial justice and equality. She discussed that technology is driving policies and urged entrepreneurs to model their business to help low-income households. She highlighted the difficulties that low income, coloured neighbourhoods face. Her talk was insightful and made me think about the effects of technology on underprivileged populations. As suggested by Jentery Sayers that blending together collaboration, experimental media, and social justice research can bring a new trajectory for American and cultural studies.

Project Showcase

Seven innovative startups presented their ideas and prototypes. Some notable projects that inspired me were:

Ovee

Ovee is a project by Jane Mitchell and Courtney Snavely. It is a platform that creates a community that supports women as they navigate reproductive health issues. Ovee is my favourite project because I can relate to the problems it is addressing.

Let’s Make History

Lead team members of the project are Ilana Bonder and Hadar Ben-Tzur. In the mobile application of Let’s Make History, a user can travel back in time to Washington Square Park through augmented reality. Users can also join Wallace and June- two young activists on a 1968 spring day, in a cinematic experience.

NYCML hosted an interesting discussion on the future of synthetic media. For some, computer-generated images, videos, text and voices can be a source of entertainment and yet, the potential for danger is extraordinary. This debate was set to address the proposition, “synthetic media will do more good than harm,”. Ken Perlin, a professor in the Department of Computer Science at New York University and Eli Pariser, an Omidyar Fellow at New America Foundation were for the proposition, arguing that synthetic media will do more good than harm. Ambassador Karen Kornbluh, Senior Fellow for Digital Policy at the Council on Foreign Relations and serves as a Governor on the U.S. Broadcasting Board of Governors and Matt Hartman, a partner at betaworks ventures were against the proposition, arguing that synthetic media will do more harm than good.

Both teams started with the definition of synthetic media. Eli Pariser explained that how simple images and videos can deceit humans by showing the audience some examples. He made a point that every source of technology can be used to harm people. His team member, Ken Pariser added to his argument, explained how synthetic media changes with time and it has been there for some time. According to him, at some point radio was a medium of manipulation. The highlight of Ken Pariser’s argument was that we need to trust the goodwill of humans. He explained entertainment usage of synthetic media.

Karen Kornbluh shared her personal experience as a policymaker and explained that how technology has been challenging democracy. Policies have been made to counter those challenges and to ensure a people’s right to information. Part of her argument was that people are evil and they are going to use synthetic media for their benefits. Her argument was very similar to one in the paper Digital Life in 2025″ Abuses and abusers will ‘evolve and scale.’ Human nature isn’t changing; there’s laziness, bullying, stalking, stupidity, pornography, dirty tricks, crime, and those who practice them have new capacity to make life miserable for others.” She further added that we need to understand the harm so that we can make policies accordingly. Matt Hartman claimed that most of the examples of synthetic media are harmful. He acknowledged the entertainment aspects of synthetic media. Referring to the current situation in USA’s Politics he added that we are witnessing the threat posed to our democracy by synthetic media.

This debate was moderated by Manoush Zomorodi, co-founder of Stable Genius Productions. Both teams presented solid arguments. In the end, I agreed with Karen Kornbluh and Matt Hartman that synthetic media has the potential to do more harm and it is important that we create policies accordingly.

Demo Expo

At the expo, students displayed emerging media and technology prototypes. It was an amazing experience for me. The astounding ideas presented by the students were motivational for me. It will be interesting to see how augmented and virtual reality are going to impact the world.

Summit’s like NYCML’18 can bring people from the tech industry and academia together, to work towards a better future for humanity in this advanced technological world.

Cited Work

Anderson and University’s – NUMBERS, FACTS AND TRENDS SHAPING THE WORLD.Pdf. https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/831785/mod_resource/content/0/PIP_Report_Future_of_the_Internet_Predictions_031114.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec. 2018.

Anderson, Janna, and Elon University’s. NUMBERS, FACTS AND TRENDS SHAPING THE WORLD. p. 61.

Larry Diamond. “Liberation Technology.” Journal of Democracy, vol. 21, no. 3, 2010, pp. 69–83. Crossref, doi:10.1353/jod.0.0190.

Larry Diamond – 2010 – Liberation Technology.Pdf. https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/831842/mod_resource/content/1/21.3.diamond.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec. 2018.

Press, The MIT. “The Invisible Computer.” The MIT Press, https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/invisible-computer. Accessed 10 Dec. 2018.

Sayers, Jentery. Technology | Keywords for American Cultural Studies. https://keywords.nyupress.org/american-cultural-studies/essay/technology/. Accessed 10 Dec. 2018.

Helpful Links

https://nycmedialab.org/

https://nycmedialab.org/prototyping-projects/

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEV0ObzNb_nFzrGS841niIA

ASIS&T Webinar: “Information Practice in International, Collaborative, Publicly Funded, Data Driven, Digital Humanities Projects”

I attended the ASIS&T webinar, “Information Practice in International, Collaborative, Publicly Funded, Data Driven, Digital Humanities Projects” presented by, Alex H. Poole (PhD), and Deborah A. Garwood (MSLIS, PhD student) from the Drexel University Department of Information Science. Within the contents of this 50 minute long presentation observations and recommendations were issued about 5 key categories of analysis relating to the grant based program Digging Into Data Challenge.

Those areas include:

- Collaborative and Interdisciplinary work

- Pedagogy and Researcher Skills

- Librarians and Archivists

- Project Management

- Data Management

Before we delve into specifics lets establish an understanding of what the Digging Into Data Challenge is.

According to their own website the goal of DID is

“–to address how “big data” changes the research landscape for the humanities and social sciences. Now that we have massive databases of materials available for research…what new, computationally-based research methods might we apply? Digging into Data challenges the research community to help create the new research infrastructure for 21st-century scholarship” (About).

Along with this mission are grants which are “sponsored by several leading research funders from around the world” (About).

The participants that are awarded these grants come from varied disciplines, and areas of research like languages, linguistics, biodiversity, law, history, political science, and media/imagery studies. Poole, and Garwood decided to analyze the third round of funded projects in practice from 2013-2016 which they call DID3. This round included 14 projects from 10 funding agencies, and 4 nations. A grand total of 5.1 million dollars were awarded to the DID3 participants.

Qualitatively they assessed 11 of these projects utilizing semi-structured interviews, documentary evidence, and scholarly output on the 5 key areas listed above. The outcome was a clearer picture of the extent of information practice, adherence to mandates, and cross-discipline challenges unique to the DID3 cohort. All 5 categories exhibited fluctuations in weaknesses and strengths among participants. For the sake of this article I will focus on 2 points I found most provoking from Poole and Garwood’s analysis and what it could suggest for evolving information practices in interdisciplinary research.

Point 1:

“Pedagogy has an important yet under exploited role in publicly funded research, particularly in digital humanities”

According to Poole, and Garwood’s study participants placed strong emphasis on domain knowledge as fundamental to their research outcomes but coincidentally experienced “steep learning curves” during the life span of their research. In fact, 21 new skills (most of them technology related) were learned by the members of the DID3 group.

This is compelling because it points toward larger possibilities for pedological advancement along interdisciplinary lines. It also affirms strengths in fields like digital humanities where collaboration between human centered questions and technology are championed and heavily experimented with. As evidenced by this study we are still negotiating ” the implications of the multilayered literacy associated with computers” (Selfe). A literacy that may be fettered by exclusionary domain practices and inflexibility within specializations.

Pedagogy must respond to the swelling need for variable research. The future is presenting, and often demanding more opportunities for blended knowledge between technological and traditional modes of study. Departments that seek “collaboration across disciplines and institutions, working with primary sources and archives, strategically selecting technologies under financial constraints, and working within networks and connecting with local communities…will ultimately rise to an ethical level of civic engagement”(Alexander and Frostdavis).

As Poole and Garwood suggest,

“We must imbricate domain types and computational expertise in data, as well as coordinate curricula among all stakeholders.”

If this cohort reveals anything it is that by expanding our pedagogy in open and “multilayered” methods, especially those with computational focuses, future research will be more representative and more prepared for our society and its digital iterations.

Point 2:

“Apparent non-involvement of information professionals (librarians and archivists) in these projects is quite deceptive as it was so foundational as to escape notice”

According to Poole and Garwood’s case study, only 5 of 53 participants in the DID3 are active librarians and archivists. What is glaringly obvious is their limited number of official contributions seem to be essential to the missions of DID3 funded research. Those contributions are:

- Physical Hosting

- Virtual Hosting

- Visualizations

- fair use and copyright

- liaison work

- User Testing

- Translation Work

- Curation

Unfortunately it seems the tenants of librarianship are being utilized regardless of their official inclusion in research. According to Poole and Garwood most researchers admitted using core competencies rooted in LIS, but never consulted a professional. Particularly worrisome is that the DID3 cohort rather inconsistently fulfilled their open data missions and opted for traditional publications which paywalled users from access, or developed websites which stopped being updated after research was finished.

One participant claimed he utilized information professionals as unofficial supporters and was simply unaware of their knowledge due to “miscommunication”. Another participant with an MLIS degree said that researchers don’t ask about her prowess due to the stereotypes that fall around “librarianship” and its competencies.

Largely these assumptions of what librarians/archivist can and can not do are a part of a cyclical historical trend where the “quest for professional status has been an area of insecurity since the beginnings of the modern profession, particularly for those relying on local authorities or remuneration”(Luthmann). Some reports suggest the “stereotype still exists within the public perception and may act as a powerful deterrent to library use“(Luthmann).

It is urgent that researchers not be admonished, but rather provided with accurate representations of the librarians at their institutions, services they provide, and comprehensive explanations of their expertise. After all, how does one gain status and respect if the credit is rarely given, or opportunities scarcely offered?

Attaining professionals versed in curation, fair use, and liaison work in a research capacity will only help with open access, and longevity. One researcher in the study admitted their librarian “could do things with data visualizations that we couldn’t” and functions like curation are “a really significant issue, otherwise your not going to be able to use this data yourself let alone make it available to anyone else.”

‘Miscommunication’ and negative tropes about librarianship will only be abolished by giving credit where it is due. Seeking librarians, and archivists early on to be included in decisions in data’s retrievability and life cycle will have long lasting effects for accessibility. Developing channels between information professionals and researchers will inevitably widen the currents of expertise, and result in a long overdue partnership of accountability and respect.

Conclusion:

Poole and Garwood’s study is crucial in how we develop effective strategies for the humanities and its scientific infrastructure.

As they point out,

“We must engage funders and researchers in a process that facilitates ongoing liaison, tracking outcomes and supporting researchers subsequent endeavors”

Presumably we must also reach across disciplinary, and professional boundaries. The byproduct of this action could be one of inclusivity and expansion on topics that could shape how we understand humanity and its residues going forward.

Works Cited

“About .” Digging Into Data, Trans-Atlantic Platform, diggingintodata.org/about.

Alexander, Bryan, and Rebecca Frostdavis. “Should Liberal Arts Campuses Do Digital Humanities? Process and Products in the Small College World.” Debates in the Digital Humanities, 2012, pp. 368–389., doi:10.5749/minnesota/9780816677948.003.0037.

Luthmann, Abigail. “Librarians, Professionalism and Image: Stereotype and Reality.” Library Review, vol. 56, no. 9, 2007, pp. 773–780., doi:10.1108/00242530710831211.

Selfe, Cynthia. “Computers in English Departments: The Rhetoric of Technopower.” ADE Bulletin, 1988, pp. 63–67., doi:10.1632/ade.90.63.

ALSC Webinar: “Advocacy for Everyone”

The Association for Library Service to Children hosted a webinar, “Advocacy for Everyone,” on Wednesday, October 3, 2018. Four panelists, moderated by librarian Africa Hands, discussed Advocacy in relation to children and youth librarianship.

The first question Hands asked was about how advocacy related to children and youth librarianship. The first speaker was Brian Hart, board member of Greensboro Public Library in North Carolina. He believed in the importance of intentionality in interacting with the public. When a librarian is deliberate in telling parents the value of bringing their children to libraries, it that e and child to be advocates for the library. He emphasized that libraries help create a civil, confident, educated society through providing to children. By giving this perspective and language to parents, parents can then go out into their own network and spread the message about the positive effects of utilizing the library. This brings in the community and provides unity, which fosters advocacy. Confidence is a large part of the work.

John Gehner’s article, “Libraries, Low-Income People, and Social Exclusion,” discussed how social exclusion can minimized by the efforts of libraries. Hart’s point about deliberate action to speaking with patrons, therefore empowering them utilize the library and be advocates, is aligned with Gehner’s idea that librarians can remove barriers that cause exclusion by doing one-on-one interactions, offering welcoming orientations, and accommodating visitors. Once libraries welcome patrons, and will patrons demonstrate the value of libraries, which then allows libraries to advocate for resources to provide even more service to the community.

A second answer for the question about advocacy was answered by Gretchen Caserotti, Library Director of Meridian Library District in Idaho. She emphasized that the work of advocacy is not insular. She pointed out the potentially strong relationship betweens libraries, schools, and other youth-related programs. With this, public speaking becomes a valuable skill for libraries because advocacy requires communication. She described it as an asset in advocacy.

Gehner’s fourth action, “Get out of the library and get to know people,” discussed this point. The article listed three points that library staff must do, the third one being “build and rebuild relationships between and among local residents, local associations, and local institutions.” As Caserotti explained in the webinar, physically going out to meet people is essential to connecting and advocating.

The next question Hands asked was about whose role it was to lobby for advocacy. Constance Moore, Vice President of Bucks County Free Library in Pennsylvania, believed it was broadly everyone’s job. Hart and Caserotti specified that different levels of government, and different groups in general, have varying roles. Hart, being a board member himself, believed that smaller organizations have more information about a local landscape, and therefore are equipped to position the library for advocacy success. Caserotti emphasized that each level of the government affects libraries, and the communities libraries serve, in multiple ways. She wanted to note the importance of considering each level, and having the “right” people for each issue. For example, a library board makes sense on a state level, where as a city council make sense on a city level.

The job of advocating by the general public is also easier with the internet. In Pew Research Center’s article, “Digital Life in 2025”, Janna Anderson noted, “political awareness and action will be facilitated and more peaceful change and public uprisings like the Arab Spring will emerge.“ Because social media allows for the general public to advocate for a mission, Moore’s push to having everyone lobby is much easier. It also allows different levels of authority to advocate simultaneously and tackle the same issue from different angles.

At the same time, there are dangers to using the internet for advocacy. There may be mixed messages or over-saturation of information. While a violent uprising is unlikely in an American library in 2018, it is possible that miscommunication can hinder advocacy rather than promoting it.

Hands’ next question asked about the process of lobbying and advocacy. Kristen Figliulo, Program Officer for Continuing Education at ALSC, believed that everything from phone calls to physically being in a room and testifying, is valuable, since legislation is a long process. She also believed in the value of building relationships before issues appear, so by the time they do, libraries feel comfortable reaching out. A way to develop a relationship includes inviting legislators for tours, sending them information about events, and overall keeping them up to date about events happening or involving the library. Figliulo also emphasized the value of building a relationship with the media. As mentioned earlier in the Pew Research article, the internet, where most of the media lives, allows for facilitation of change.

One issue Hands brought up was the issue of the boundaries of advocacy. Caserotti believed that context is important. For example, public agencies may not always allow public funds to be used for advocacy. Therefore, advocacy may have to come from different positions. Being “on the clock” versus “off the clock” affects how a message may be interpreted. Returning to Gehner’s article, the fifth action was, “understand that charity is not dignity; dignity is inclusion.” Advocacy allows for inclusion, but aggressive, blind, thoughtless advocacy may create what Gehner described as a “disconnect between saying we serve everyone and actually doing so.” In advocacy, the position of not only the community, but the librarians, must also be considered.

The final question asked the panelists, what is one small act of advocacy that you can do every day as a library employee? Hart, coming full circle, believed that confidence and openness to speaking about the positive effects of the library on the community. Caserotti emphasized the value of statistics. Reference clicking and program attendance are few of the ways to quantify the value of a library. She also described the “share up” idea. Librarians may hear about stories every day in the stacks, but directors such as herself don’t hear the stories. She believed that if librarians trained themselves to share the stories of the library doing good for the community, it empowers her, as a leader, to do more.

The webinar addressed many issues in the context of children and youth librarianship. However, many points about advocacy are applicable to the wider reach of librarianship, and information science as a whole. From finding the “right person” for the right level of government, to the data tracking and face-to-face communication of a larger public, actions for advocacy can be applied across a range of institutions, organizations, and missions.

Alvina Lai

Fall 2018