“Chinese characters are innocent,” said MIT-educated Chinese scholar Zhou Houkun in 1915 and quoted by the curators at the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) as a radical introduction to an exhibition titled Radical Machines: Chinese in the Information Age. Set in the special exhibitions gallery, the exhibition is curated by Dr. Tom Mullaney from Stanford University. Exhibition materials range from archival documents, books, video clips, photographs, and the most eye-catching, rarely-seen vintage Chinese typewriters. Most of the items belong to Mullaney’s personal collection, which is “the largest Chinese and Pan-Asian typewriter and information and technology collection in the world” (mocanyc.org). This collection was formed along with the development of Mullaney’s years of scholarship at the intersection of East Asian history, history of science and technology, and transnational/international affairs.

The radicalness, nurtured within the complex machines themselves, also sits in the nature of the Chinese language, together with many other languages from the East, being non alphabetical and thus having faced and still facing constraints in having a smooth merge with modern information technologies particularly on the end of inputting. This curatorial project as well as Mullaney’s research thus aim to be a unique introduction to this less known piece of history and a provocation to the Western dominance structured around information technologies.

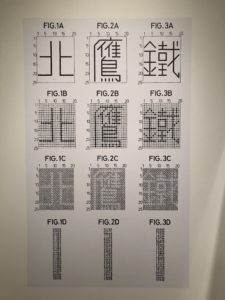

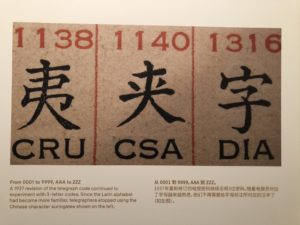

The exhibition was divided into multiple sections, drawing curious visitors first into an brief overview of the Chinese language, characters and phonetics, and the early history of printing press — Movable Type. Departing from there, since the base of written Chinese involves largely pictograph, morphing the characters into something more systematic emerged as one approach to “alphabetize” Chinese (see photo). On the other hand, the section titled Chinese Telegraphy introduces a second approach of assigning a combination of Latin letters to each of the commonly used characters. Traced back to 1870s, this method seems to be the starting point when the Chinese language was equated to English in order to adhere to the development of information technology and people’s communication needs.

Evolution of technology and shifting mode of communication have been increasingly intertwined. To answer the question of how communication defines social existence and shapes human development, exploring the history of communication technologies, from speech and language, writing, to printing press, gives us a developmental model to discuss Internet, as the agreed fourth one (McChesney, 69). The exhibition pretty much follows this itinerary when it takes visitors to explore the following two sections: Beyond QWERTY, The Typist in China.

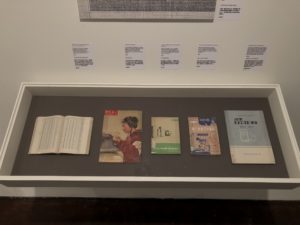

Beyond QWERTY exhibits several systems developed in history for inputting Chinese language, from the common word usage system, to later developed Wubi system, namely entering stroke-by-stroke. The section illustrates how information technology involves a large degree of customization due to the varying linguistic composition of languages. Therefore, learning how to type on a QWERTY keyboard becomes a less intuitive task for Chinese speakers. The Typist in China introduces the cultural history of learning to type using different methods, stroke-by-stroke Wubi or the phonetic method Pinyin. Echoing pieces of Western history, learning how to type, from textbooks and illustrations, became an appreciated skill for various professions. This is also very reminiscent for me as growing up in China, we also spent a good amount of time learning how to type and recently there’s also a discussion around that since Pinyin is easier to learn and few people can now use the Wubi method to type.

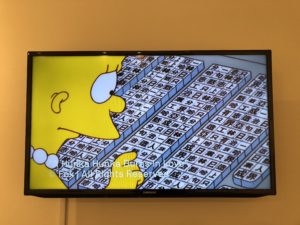

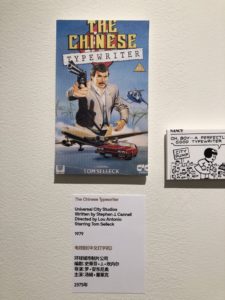

Personally a highlight of this exhibition turned out to be a section in the back of the gallery, named Western Perceptions. Absolutely less discussed, this section, including historical Western views of Chinese information technology presented in the realm of media and entertainment, attends to the issue from a cultural perspective. One will find video clips of Lisa Simpson and James Bond perplexed by a Chinese keyboard, Nancy in the cartoon puzzled by a Chinese typewriter found in the city dump. These manifestations carry a strong racist overtone, mocking the Chinese language being non-systematic, irrational, and thus not modern enough to keep up with modern technology.

Obviously there’s issues around class and accessibility, but most often we perceive technology to be culturally neutral, or that technology even being a way to culturally collectivize human beings. Yet, Radical Machines tells us that technologies could also be racialized and the prejudice reflects what has been projected onto its users. Though framed under the umbrella ideas of language, information, and technology, the curators also sought to integrate “difficult heritage” — “pasts that are meaningful in the present but that are also contested and awkward for public reconciliation with a positive self-affirming contemporary identity” (MacDonald, 6) — into this exhibition. MacDonald in her research discusses that the task of tackling difficult heritage is indeed hard for museum and heritage institutions, in that on the one hand, museums, as public educational institutions with a sound voice, must take on the responsibility in addressing difficulty heritage, and gladly according to research observation, an increasing number of institutions are willing to do so (MacDonald, 16). On the other hand, how to address difficult heritage in a provoking yet equally inviting way always needs extensive discussion. MOCA has been an active participant in exhibiting difficult heritage: narratives in this particular section of Radical Machines resonate with those in the permanent exhibition next door, “Within a Single Step: Stories in the Making of America.”

Continuing with the socio-cultural perspective, the curator took this aspect to mark an end of this exhibition — “China is the world’s largest IT market? Isn’t it the time we knew it’s history?” Linking the past to present, Radical Machines: Chinese in the Information Age successfully raises the dialogue on information, language, and technology with a unique lens. To learn more on this topic, Dr. Tom Mullaney’s blog, though not updated in a while, has a handful of interesting articles.

Bibliography

MacDonald S. (2015). Is “difficult heritage” still difficult?. Museum International, 67, 6-22.

McChesney, R. W. (2013). How can the political economy of communication help us understand the Internet? In Digital disconnect: How capitalism is turning the Internet against democracy. New York: The New Press.

Museum of Chinese in America. (2018). Radical machines: Chinese in the information age. Retrieved from http://www.mocanyc.org/exhibitions/radical_machines