The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the largest art museum in US and the third most visited art museum in the world. The main building in Manhattan’s Upper East Side in one of the world’s largest art galleries. As was posted on January 4, 2019 that 1,659,647 visitors were attracted to The Met Fifth Avenue and The Met Cloisters from May 10, 2018 to October 8, 2018. Based on the data from Wikipedia and MET official website, with such large number of visitors from all over the world, I began to curious how the visit guide provided by the museum service did well in considering different kinds of visitors.

According to what I learnt from Design Justice, the tour guide designed by MET should aim to ensure a more equitable distribution of the benefits and in this case, the museum tour guide should also consider non-English speakers, people with disabled, etc.

I went to The Met Fifth Avenue on 27th, Sep. to directly observe as a visitor and my goal was to see whether different kinds of visitors were guided friendly and effectively in visiting the museum. It was a cloudy afternoon with crowded visitors, and I waited for 10 minutes in line to get my ticket.

1 Manual Guide

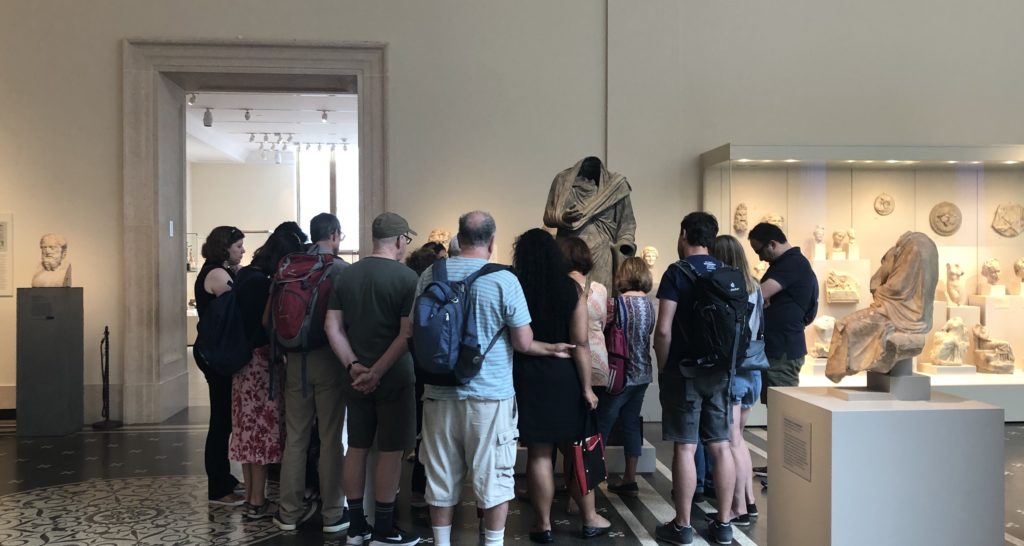

I saw several cicerones surrounded by a small number of visitors. I joined them for free. Some visitors followed by cicerones carried backpacks and not seemed like locals. The good thing for getting a manual guide is that you could directly ask questions and get answers, especially for history or art fanatics who are always filled with questions.

But this method is not that feasible for visitors who prefer to get through the museum quickly and are not fluently English speakers. Since you are guided by a certain route and listening to deep explanations of the exhibits really takes time. In this period, I found some of visitors would only follow a few minutes then left the group to visit by themselves.

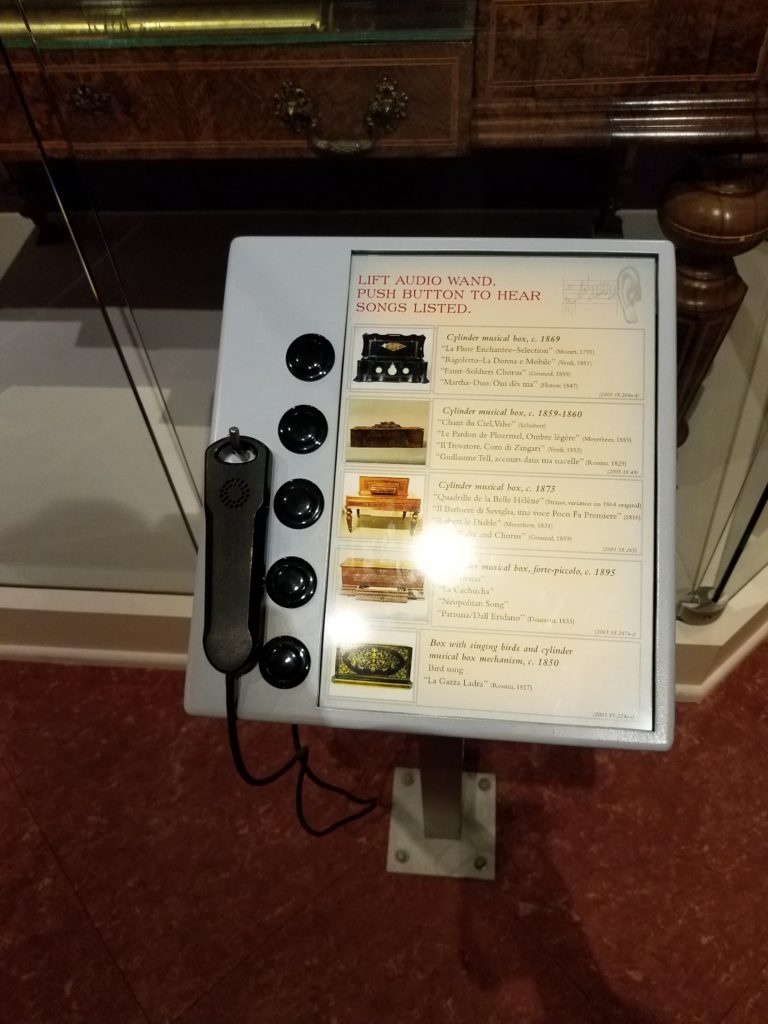

2 Audio Guide Rent Onsite

These days the most commonly used tour guide in museum is audio guide. At the museum lobby visitors could easily find the words “Audio Guide”, and the return place was also obvious to find. During my observation period, I found no more than 50% visitors were using audio guide and I guess it was because the audio guide in MET was not free, or some were not first-time visitors or some just preferred to quickly visit the whole museum without deep explanations.

2.1 Whether considering non-English speakers.

Yes. The audio guide provided by MET contains 10 different languages, which is especially considerable for foreign visitors. When I visited the museum, I found a lot of Asian visitors renting audio guide and listening to the guide frequently. It’s much effective for them to get the explanations in their mother language.

2.2 Whether considering visitors with disabilities.

During my observation period, I did not find disabled visitors. But I found some information on the MET website that the museum offered assistive listening devices and real-time captioning for visitors with hearing loss.

2.3 Whether considering aged visitors.

I found an old woman who seemed uneasy to input numbers into the audio guide to get the explanations. And some visitors seemed tired to hold the guide near their ears to listen all the time and they needed to find a place to sit or change to another hand to hold the guide. I think the interaction method between visitors and audio guides is not that friendly especially for aged visitors. Manually inputting numbers could waste time. Besides, the guide is not that easy and convenient while the MET is large, and most visitors would stay more than 2 hours.

I guess it’s better to add automatic induction function to the audio guide and visitors don’t need to input numbers themselves but only to answer yes or no to listen the guide. In addition, always holding the guide near ear to listen is not convenient. Why not provide earphones to aged visitors together with audio guide? Or support the visitors using their own earphones.

2.4 Whether considering visitors who prefer quickly visiting the whole museum.

I did find a visitor hanging the audio guide around her neck, but she didn’t use it during the whole process. And some only listened a few seconds then gave it up. I guess the contents provided in audio guide were too long and they only wanted to get a concise version. They came to the museum to get something new but not preferred to get that deep understanding towards a single exhibit. In that case, perhaps better to provide different versions for visitors to choose from. For instance, a quick 1-minute explanation together with a detailed 5-minute version.

3 The MET App

There is an App called The MET which also provides travel guides and even augmented reality function. The good thing is you could use it offline, while the bad thing is that you have to download it beforehand. How many visitors would take trouble to download an App to help them visit the museum? I guess better to develop a Web App for visitors who just want to visit temporarily.

During my observation period, I only saw a young woman using her iPhone to get the audio guide. Generally speaking, not a large number of visitors choose to get a guide on App. I believed one of the problems was not enough contents on App, compared to the audio guide you rent onsite.

Conclusion

In 2015, the MET did a thorough research on how to improve the audio guide and during the research they did find 40% visitors were foreigners and the importance of reducing the complexity of using audio guide. However, just like what Norman said, “The world is not neat and tidy and things not always work as planned.” All the tour guides provided by MET are roughly satisfied but still have space to improve. Perhaps reconsidering different visitors’ needs could help better the overall experience.

Reference

1 Wikipedia: Metropolitan Museum of Art: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art

2 Met Welcomes Nearly 7.4 Million Visitors in 2018:

https://www.metmuseum.org/press/news/2019/2018-calendar-year-attendance

3 Improving the Audio Guide: A Look at Our Visitors:

4 Norman, D. A. (1998). The Invisible Computer: Why Good Products Can Fail, the Personal Computer is So Complex, and Information Appliances are the Solution. MIT Press. Chapter 7: Being Analog http://www.jnd.org/dn.mss/being_analog.html.

5 Costanza-Chock, “Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice”