The event I attend for this blog post was hosted by The Center for Humanities Graduate Center, CUNY. The Center aims to create cross-departmental collaboration and encourage creative work between the humanities at CUNY. Through free exhibition and public programming, the Center also aims to engage with a “diverse intellectual community” across the city (“About,” n.d.). The event was the first in a semester long working-group in conjunction with an exhibition titled, Institutional Apparatuses, or, Museum as Form. The working-group aims to focus discussions on how “museums reflexively grappled with their ethical obligations” and the growing movement within the field to shed light on and critique these political and ethical dynamics (“About,” n.d.). Each bi-weekly discussion will feature guests from various cultural institutions, from the Artist Director of Rhizome to a curator at The Studio Museum. Institutional Apparatuses, or, Museum as Form is organized by two fellows at CUNY, Kirsten Gill and Lauren Rosenblum.

I attended a discussion between main speaker Michelle Millar Fisher, Curator of Contemporary Decorative Arts at MFA Boston and Nikki Columbus, a curator who’s known in the art world for having sued MoMa PS1 over discrimination. The title for the working-group was, Michelle Millar Fisher and the Art/Museum Salary Transparency Project: Administration and Wage Labor in the Contemporary Museum.

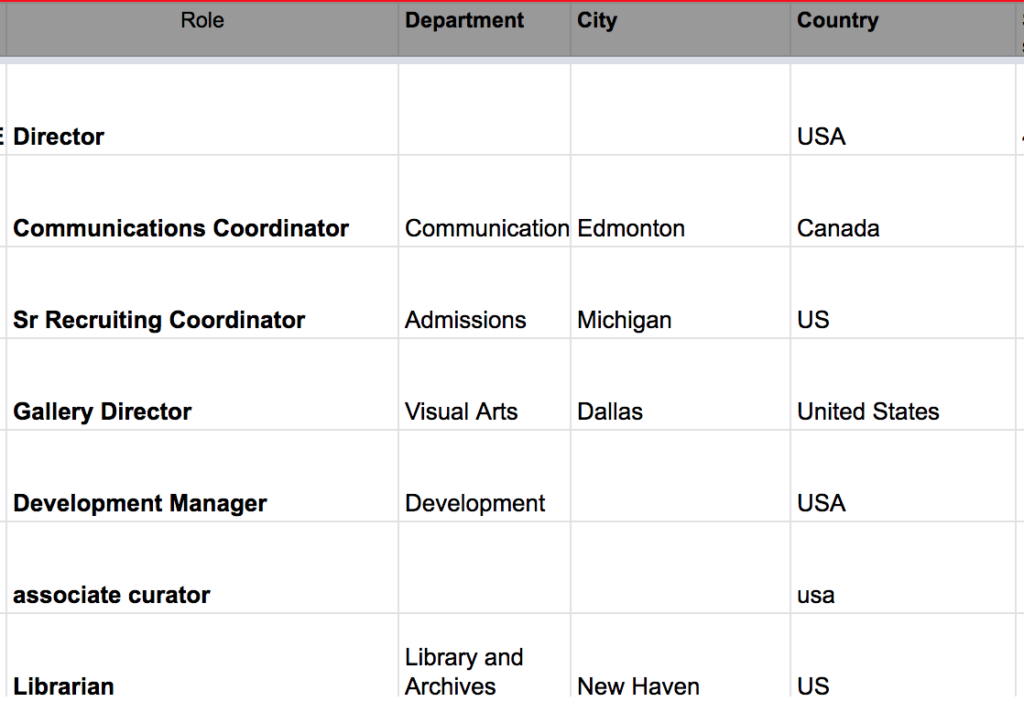

In line with themes of transparency, it should be noted that Fisher and I worked in separate divisions at the same time at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) before both leaving this past summer, her for MFA Boston and me to attend Pratt. We were both still employed at the PMA in May when she co-organized the Art/Museum Salary Transparency Project, an open-source spreadsheet for art workers to anonymously post their institution of employment, salaries, and demographic details. Since the release and sharing of the spreadsheet there has been continual momentum in the museum–and I believe the cultural heritage field at large–to hold institutions accountable for how they manage internal structures and their staffing. The event and discussion applies to the information field thematically, as information professionals, art handlers, and curatorial assistants, to name a few, all play behind-the-scenes roles within their institutions of employment. The information mechanisms that Michelle and her collaborators used to disseminate their call to arms are also examples of how information tools like Google Sheets and platforms like Twitter can impact social networks.

Fisher FaceTimed from her office in Boston to participate. The discussion began with a brief backstory on what motivated her to create and share a public spreadsheet of museum positions and salaries. Anyone that has worked in a large museum (though not limited to museums) has experienced the “economic inequalities manifest[ed] in cultural institutions,” as well as the lack of transparency in salary distribution and demographic diversity (Small, 2019). The goal of the open-source spreadsheet was and is to encourage salary transparency in the cultural heritage sector while also “contribute to further diversifying the field across socioeconomic categories” (Small, 2019).

The Art/Museum Salary Transparency Project is not the first example of a collective push for salary transparency. POWArt released a Salary Survey in 2018 and published their results as an info graphic in 2019. Nor is it the first Google Sheet to be used within an industry to address issues of concern. The “Shitty Men in Media” list from the #metoo movement was a Google spreadsheet, collating isolated events by victims and shared to warn others. Beyond my conceptual interest in these conversations, I’m also intrigued by how the ease of access to collaborative document editors like Google Sheets has empowered users to make and share databases. The past few week’s readings on UX and HCI also beg the question, what were the original design intentions of Google Docs and Sheets? Did the designers at Google predict these political examples of use?

Collaborative document editors like GoogleDocs and open-source text editors like Etherpad in a way embody the founding essence of the World Wide Web. These collaborative documents are situated in a linked network of users. Granted, like most database systems, an information system needs to be put in place to ensure consistency. When the Art/Museum Salary Transparency Project came out any anonymous user could edit and add to the document. It was exciting to see the rows of anonymous animal avatars grow and new fields of information multiply. But it also served as an example of collective chaos when every user is also an editor. Eventually the co-founders created a separate submission form for entries and suggestions, and the original Google spreadsheet is public for viewing only. Note: the submission form mitigates the need for having a Gmail account to participate.

The evolution of Fisher’s and her co-creators’ document is an apt example demonstrating a knowledge organization system trying to democratize salary, benefits, and demographic statistics. It focuses on a survey-based method to create a bottom-up approach to distributing analytical data. However, considering Sasha Costanza-Chock’s article on Design Justice, it should be acknowledged that with any designed system there are still flaws. Context can be lost when trying to make data conform to a set format. Employees from museums may worry that their employers might react negatively to participation. Fisher noted herself that she was lucky to have secured a position already at the MFA Boston, when the spreadsheet was posted—some her co-creators at the time and even now are still anonymous for fear of employment retaliation.

Further broadening the scope and range of their project, the co-creators started a Twitter account @AMTransparency that has become a centralized informal museum job posting watchdog. A few months ago, the account called attention to The Morgan Library for “replacing essential roles that should be good paying jobs” with volunteer job postings, one requiring a Phd in medieval art history (@AMTranpsarency, 2019). The Morgan Library later removed these postings from their website. Art+Museum Transparency is pushing for museums and the cultural heritage sector at large to be held accountable for the labor their institutions are built on.

Another facet of the evenings discussion focused on internships for credit, which some consider as a loophole for labor under NY State Labor Standards. We touched on this briefly during our class exercise discussion on a code of ethics for students at Pratt. Should the Pratt listserv repost unpaid internships and volunteer work? Does circulating these postings help to encourage institutions to continue to function on unpaid labor? Personally, my biggest hesitation from completing an advanced certificate is the required practicum and internship for credit. For the Archives track, I understand that this is a larger conversation with SAA certificate qualifications, however paying to intern in any context is a financial barrier for many students.

In conclusion, though the event was focused on art museums, the topics discussed apply to many facets in the information field. Museums also include archives and libraries, and make up a large portion of the cultural heritage sector. The discussion also acted as an informal case study of how users can adapt designed tools like Google Sheets as new forms of community building and methods of disseminating knowledge. Yet there are still important questions about who will be responsible for documenting and preserving the open-sourced used of spreadsheets like the Art/Museum Salary Transparency Project. Will collective documents like this live in an archive? What will the metadata look like for a document with so many co-creators built on anonymity?

Sources

About. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2019, from The Center for the Humanities website: https://www.centerforthehumanities.org/about

GPAS Curriculum | Society of American Archivists. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2019, from https://www2.archivists.org/prof-education/graduate/gpas/curriculum

Michelle Millar Fisher and the Art/Museum Salary Transparency Project: Administration and Wage Labor in the Contemporary Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2019, from The Center for the Humanities website: https://www.centerforthehumanities.org/programming/michelle-millar-fisher-and-the-art-museum-salary-transparency-project-administration-and-wage-labor-in-the-contemporary-museum

Small, Zachary (2019, June 3). Museum workers share their salaries and urge industry-wide reform. Retrieved October 12, 2019, from https://hyperallergic.com/503089/museum-workers-share-their-salaries-and-urge-industry-wide-reform/

Transparency, A. + M. (2019, August 11). A volunteer departmental research assistant for the manuscripts department. Phd required. Reading knowledge of French and German. Accruing that experience takes time and debt. You’re a major NYC museum. What’s going on @MorganLibrary, are you hurting for money?? Let’s see… /2pic.twitter.com/zEIzXpNTAX [Tweet]. Retrieved October 12, 2019, from @AMTransparency website: https://twitter.com/AMTransparency/status/1160592964374212608