Private Tour to Frick Art Reference Collection.

In their roles of preserving tangible and intangible heritage, museums have documented a corpus of knowledge that is fundamental for societies. However, this orientation, which has paid more attention to artifacts, is one of the reasons why museums are perceived as distant institutions that are more concerned with the past, and that are more at the service of the intellectual elite of the museums (MacDonald and Alsford, 2010). Consequently, museums, beyond being places to collect, preserve, study, and exhibit, are redefining themselves and making efforts to respond to a fast paced information society by incorporating more interactive museum management information technologies.

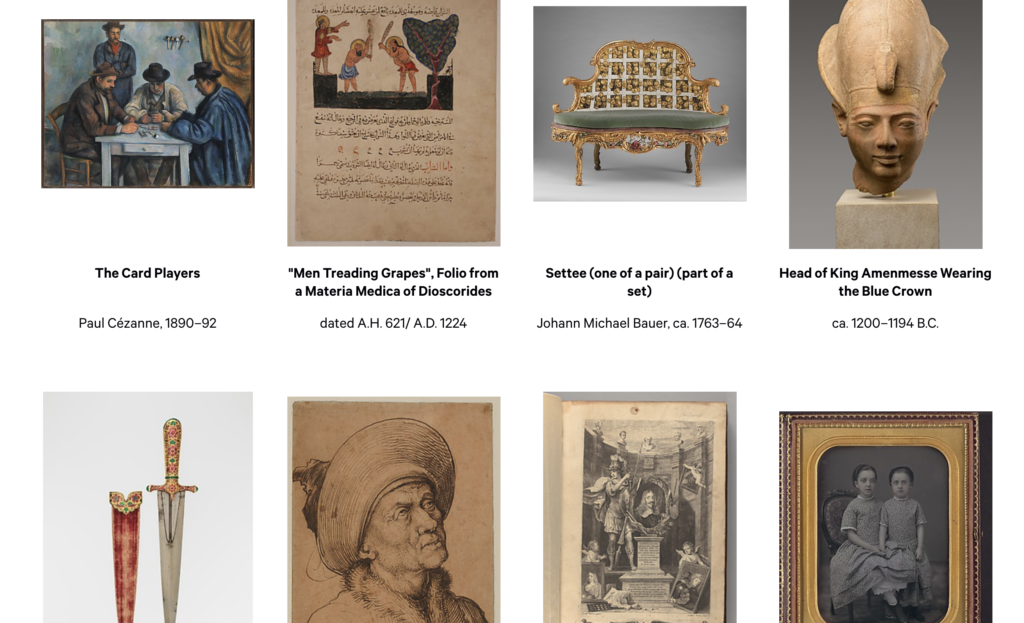

Frick Art Reference collection is a leading organization for digitizing their collection it is dedicated their resources to collect, preserve, study, exhibit, and shared through online. Frick Art Reference Library’s mission is to provide public access to materials and programs related to the study of fine and decorative arts created in the Western tradition from the fourth to the twentieth century.

Entering Frick Art Reference Library(FARL)

In order to visit the Frick Art Reference Library, you need to be 18 and older and you need to be registered or pre-registered through online. for security issue Coats, umbrellas, camera, and laptop cases, and bags larger than 9″ x 12″ x 3″ must be checked.

Stephen J. Bury

Stephen J. Bury is a scholar, art historian and the Andrew W. Mellon Chief Librarian of the Frick Art Reference Library in New York City. Meeting Stephen J. Bury was a strange experience to me, especially right after I read his essay about his plans about digitalizing Frick Collection: Embedding a culture of innovation at the Frick art reference library in Technology and digital initiatives: innovative approaches for museums / edited by Juilee Decker. He introduced ARIES and equipment they use for documenting works.

ARIES: ARt Image Exploration Space

Louisa Wood Ruby, the Head of Research at The Frick Art Reference Library gave us to talk about the open source program they developed. As an emerging museum and digital culture professionals, I hope to create a culture of openness and accessibility in museums, so that visitors can reduce their fear of institutions and have a better understanding of the contents of collections and exhibitions. ARIES is the perfect example for Libraries in incorporating technologies.

ARIES is an open source developed by members of the Digital Art History Lab (DAHL) collaborated with New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering and the Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazill. This program is originally created to help to visually compare the artwork it saves tremendous time for art historian and curator.

ARIES follows Sir Tim Berners-Lee’s theory of “information management” system and it became the conceptual and architectural structure for the Web. Berners-Lee eventually released the code for his system — for free — It became a milestone in easing the way for ordinary people to access documents and interact over the Internet. (Digital life in 2025: Experts predict the internet will become ‘like electricity’-less visible, yet more deeply embedded in people’s lives for good and ill by Prof. Janna Anderson, Lee Rainie)https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/831785/mod_resource/content/0/PIP_Report_Future_of_the_Internet_Predictions_031114.pdf

ARIES is free program for all and it is designed not just for the art historian and researcher, it is designed for everyone who is interest in the collection in Frick Art Reference Library(FARL)

Art historians have traditionally used physical light boxes to prepare exhibits or curate collections. which is exhausting and time-consuming ARIES is created to address problems. It is an image Exploration Space, an interactive image manipulation system that enables the exploration and organization of fine digital art. The system allows images to be compared in multiple ways, offering dynamic overlays analogous to a physical light box, and supporting advanced image comparisons and feature-matching functions, available through computational image processing.

ARIES is still under the development and they recently added tracking program for dispersal of an artist’s work. Tacking work would be really useful for curating exhibitions.

I attended an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized by Professor Villaespesa for Info School students. While there, we heard from Loic Tallon, the museum’s Chief Digital Officer, and Jennie Choi, the General Manager of Collection Information. We heard about their work at the museum and their approaches to the idea of digital at an institution as large and as entrenched in its ways as the Met can be.

I attended an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized by Professor Villaespesa for Info School students. While there, we heard from Loic Tallon, the museum’s Chief Digital Officer, and Jennie Choi, the General Manager of Collection Information. We heard about their work at the museum and their approaches to the idea of digital at an institution as large and as entrenched in its ways as the Met can be.

Notebook wallpaper from Martos Gallery exhibit

Notebook wallpaper from Martos Gallery exhibit