I attended an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized by Professor Villaespesa for Info School students. While there, we heard from Loic Tallon, the museum’s Chief Digital Officer, and Jennie Choi, the General Manager of Collection Information. We heard about their work at the museum and their approaches to the idea of digital at an institution as large and as entrenched in its ways as the Met can be.

I attended an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized by Professor Villaespesa for Info School students. While there, we heard from Loic Tallon, the museum’s Chief Digital Officer, and Jennie Choi, the General Manager of Collection Information. We heard about their work at the museum and their approaches to the idea of digital at an institution as large and as entrenched in its ways as the Met can be.

One of Tallon’s central theses to his work at the Met is that “the strategy of centralizing responsibility for digital transformation within a single, distinct department is reaching its limits. Now a broader institutional approach is needed.” It’s a theme he’s written on for the Met’s blog and a topic he discussed during his talk. The boundaries for digital initiatives in museums are wavy, indistinct lines. In his blog post, he charts out different responsibilities that fall under the scope of “digital” at various museums around the country. No two museums approach it the same way, and it comes increasingly reductive to limit certain processes to a digital department, when the reality is that all departments should be examining their workflows for places they can adapt and embrace new technologies.

At the Met, the Digital department is comprised of three teams: a team dedicated to collections information and data management, a team of content producers, and a team for product development. Tallon described their work as divided between the two paths people can take to interact with the museum. The first path is the in person experience. When a visitor enters the Met’s physical spaces, what work can the digital team do to enhance their experience? The second path is for the remote user, who interacts with the Met’s collection and its services online. What does the digital team need to accomplish to present the museum to the rest of the world?

The first path is generally constrained by space and exhibit demands, but the possibilities for the second path are wide open. The questions regarding digital at the Met are similar to the ones the High asked itself for its physical gallery reinstallation. How does a museum stay relevant, provide the best representation of its collection, and engage with as many people as possible?

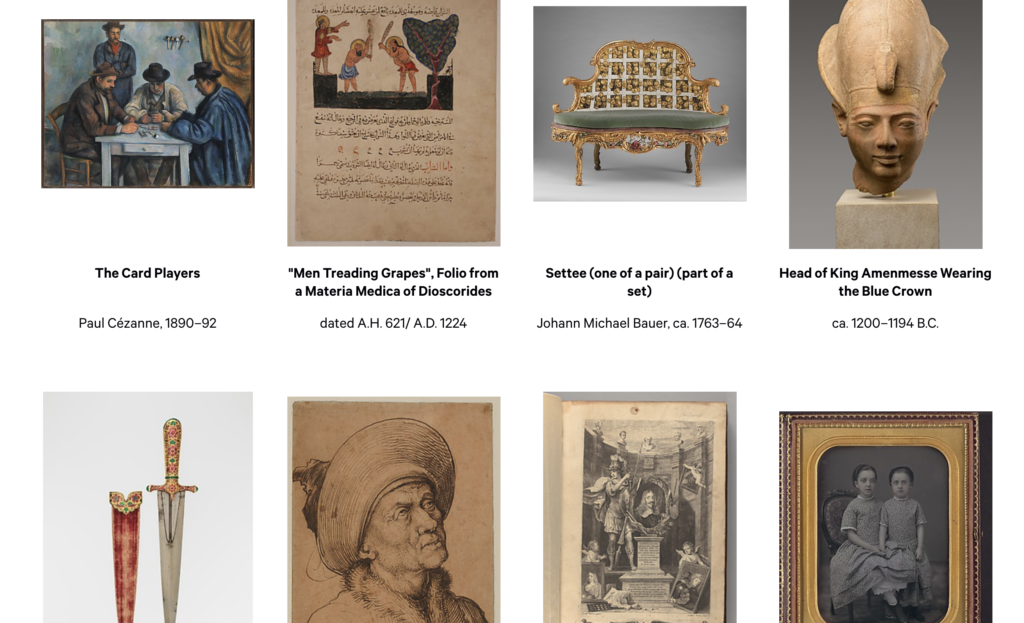

At the Met, the answer was to invest more heavily in digital. Tallon admitted that the museum’s online presence had very little effect on the museum’s bottom line. And yet, it’s a presence worth building on as the world increasingly engages with itself online. Last year, the Met launched it’s Open Access intiative. They made high quality images of their public domain collection available to anyone under a Creative Commons Zero license and worked with Wikimedia and Google to make their images more accessible on the web. Just last month in October, they made those images along with information about all the works in the museum’s collection available via API.

Since the launch of the Open Access initiative, the Met has been able to reach a larger audience with images from their collection. While it hasn’t resulted in a significant increase in traffic to the Met’s website, its images are available on Wikipedia pages and Google search results. These other platforms allow a wider audience to engage with the Met’s collection, including users who speak a language other than English–something the Met itself would never have been able to do on its own. The API is only a month old, so results remain to be seen. Those interested in updates should keep an eye on Tallon’s posts on the Met’s blog.

In the second half, we heard from Jennie Choi, General Manager of Collection Information. With over 20 years of experience at the Met, she had some really interesting insights into the museum’s metadata. The primary piece of software used at the Met is The Museum System, a full collections management system that feeds its information into other parts of the Met, including NetX, the museum’s digital asset management system, and the museum’s information kiosks.

The Met has a long history of making and keeping records on its collection, but it’s only in the last few years that it has created a set of cataloguing standards and worked across departments to standardize data like artist names and object provenance. Previously, each curatorial department was responsible for its own records, which created heavy inconsistencies in how works were labeled and could be found online. Choi was on a team that worked with curators over two years to bring all that metadata under one roof and continues to work with departments to bulk out information available on works from the collection.

Choi’s latest project is tagging works from the collection with content keywords–something that’s never previously been done. In an initial pass through the collection, the museum outsourced the work to a team of 70 who worked 24/7 for three months to assign various tags to works. They looked for things like objects featured in paintings, or whether the work depicted a man or woman. There have already been major challenges to this. Using such a large group of taggers created inconsistencies, and the lack of a standard created inaccuracies. There were also cultural differences that hindered the quality of the documentation. For example, it was hard for the team to accurately identify satire in the drawings collection. Given the opportunity to do it again, Choi says she would’ve preferred to work with a smaller team with more training over a longer period of time. Due to the nature of the project funding, the initial work had to be completed within three months and the tags need to be reviewed before they can be added to public-facing systems.

I thought this was a fascinating look behind the digital initiatives at the Met. It felt perfectly in line with my observation of the High. Both institutions are in the midst of interrogating their stewardship of their respective collections. In the High’s case, it was of their actual physical space. For the Met, a full scale physical reorganization is improbable, but they have untapped potential in carving out a digital space of their own.