Person: Ada Lovelace

Ada Lovelace (1815-1852) was an English mathematician and writer known to have written the first algorithm ever, way before computers existed. She worked with Charles Babbage (1791-1871), the inventor of the Analytical Engine, a project for a mechanical general-purpose computer. In 1842 Babbage asked Ada Lovelace to translate a review made by an Italian mathematician of his Analytical Engine. The result was the translated review plus a set of notes explaining how the machine could work and what kind of computing it could make. One of the notes was a detailed method for computing the Bernoulli numbers, a calculus of math theory, using the Analytical Engine. This set of instructions to be done by a specific machine to produce something more than a calculation is known as the first algorithm and because of it, Ada Lovelace is also known as the first computer programmer.

At that time it was not common that women were trained in maths or science as she was. Ada was the daughter of the famous English poet Lord Byron and Annabella Milbanke, Lady Byron who was also trained in mathematics. Her mother made sure that she got a solid science and overall education through private tutors so that Ada would keep away from the insanity she accused Lord Byron of. Thanks to one of her tutors, at a very young age Ada Lovelace met Charles Babbage and despite the age difference, they worked as peers. Babbage recognized Lovelace’s analytic skills and outstanding intellect calling her “The Enchantress of Numbers”.

Ada Lovelace’s contribution was not only the algorithm itself but in the set of notes, she also wrote about her auspicious vision of what the Analytical Engine could achieve.

The operating mechanism can even be thrown into action independently of any object to operate upon (although of course no result could then be developed). Again, it might act upon other things besides number, were objects found whose mutual fundamental relations could be expressed by those of the abstract science of operations, and which should be also susceptible of adaptations to the action of the operating notation and mechanism of the engine. Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expressions and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent. (1)

Ada Lovelace was definitely ahead of her time. The first actual computer came to life around a century later and it, in fact, accomplished what she envisioned.

Place: Brooklyn Public Library

Brooklyn Public Library Central Library is one of the most iconic buildings in Brooklyn. The construction of the building started in 1912 commanded by architect Raymond F. Allmirall but it didn’t open to the public until 1941. The structure is built to resemble an open book, with its spine facing Grand Army Plaza. The great entrance is ornamented with fifteen sculptures of famous characters from American literature like The Raven from the poem by Edgar Allan Poe, Tom Sawyer from the novels of Mark Twain and Moby Dick from the novel by Herman Melville. The entrance also has two massive columns decorated with reliefs representing the evolution of arts and sciences.

My favorite collection within the library is the Brooklyn Collection, a collection of documents of Brooklyn from pre-colonial times to the present that includes books, photographs, newspapers, maps, atlases, directories, prints, illustrations, and posters among other media. In this collection, I could see the designs and photos of the construction of the subway station I use every day.

The Central Library consists of 352,000 sq feet organized in ten different departments and collections offering numerous programs and services. One of the services that I use the most is the Shelby White and Leon Levy Information Commons that offers a wide range of programming related to digital media and technology. There is an amateur recording studio equipped with and editing workstation that I used for recording an episode of a podcast.

Reflecting about BPL’s services and collections takes me back to the text about Information Ecologies by Nardi and O’Day (1999) where they go beyond considering a library as a place for accessing information, focusing on the relationships within the ecology of the library, including the relationship between people, people, and their environment, and people and technology.

Thing: Personal Computer

The access to information we have today wouldn’t be possible without two things: the internet and personal computers. Before turning into a mass consumer electronic device, computers were used by experts in scientific settings. The earliest example of a personal computer, meaning a computer made for a single user, dates from 1956. The LGP-30 developed by physicist Stan Frankel was meant to be used for science and engineering as well as simple data processing, the price of the LGP-30 was $55,000, a good price for that type of machine at that time.

In 1962 MIT Lincoln Laboratory engineer Wesley Clark designed the LINC, which was meant to function in a laboratory setting. Some end-users from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) participated in a workshop at MIT where they built their own LINCs and brought back to their own institutions.

In 1965’s New York World’s Fair appeared Olivetti Programma 101, which was the first to be described as a desktop computer. 40,000 units were sold including 10 sold to NASA for use on the Apollo space project. The cost of the Olivetti Programma 101 was $3,200. Let’s jump to the year 1971 when the Kenbak-1 was released. This is considered the earliest personal computer by the Computer History Museum. It was designed by John Blankenbaker and the price was $750.

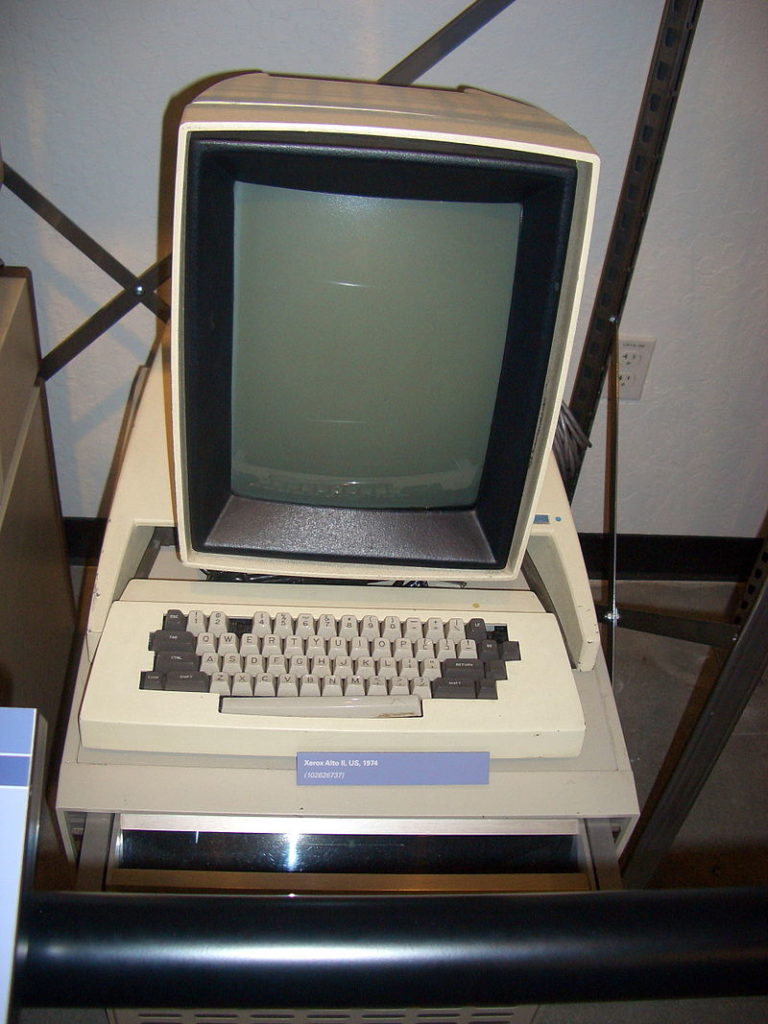

The world would have to wait until 1973 to see a personal computer that looks somewhat like the computers we know today. The Xerox Alto had a graphical user interface (GUI) with windows, icons, and mouse. It also allowed users to print documents and share files. As per the software it had a word processor, a paint program, a graphics editor and email. From that moment fort the development of personal computers occurred rapidly and all the designs that came after the Xerox Alto were in one way or another inspired by it.

End notes

(1) Menabrea, Luigi Federico; Lovelace, Ada (1843). “Sketch of the Analytical Engine invented by Charles Babbage, with notes by the translator. Translated by Ada Lovelace”. http://www.fourmilab.ch/babbage/sketch.html

Resources

Brooklyn Public Library Website www.bklynlibrary.org

Computer History Museum Website https://computerhistory.org

Essinger, J. (2014). Ada’s algorithm : how Lord Byron’s daughter Ada Lovelace launched the digital age. Melville House.

Meriwether, D. H. (2018). Ada Lovelace. Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.pratt.edu:2048/eds/detail/detail?vid=3&sid=e89df074-5928-4a07-ac04-f9a65ce05cb7%40sessionmgr4006&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#AN=88806839&db=ers

Nardi, B. & Day, V. L. (1999). Information Ecologies: Using Technology with Heart.First Monday, 4(5), May 3, 1999. https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/672/582