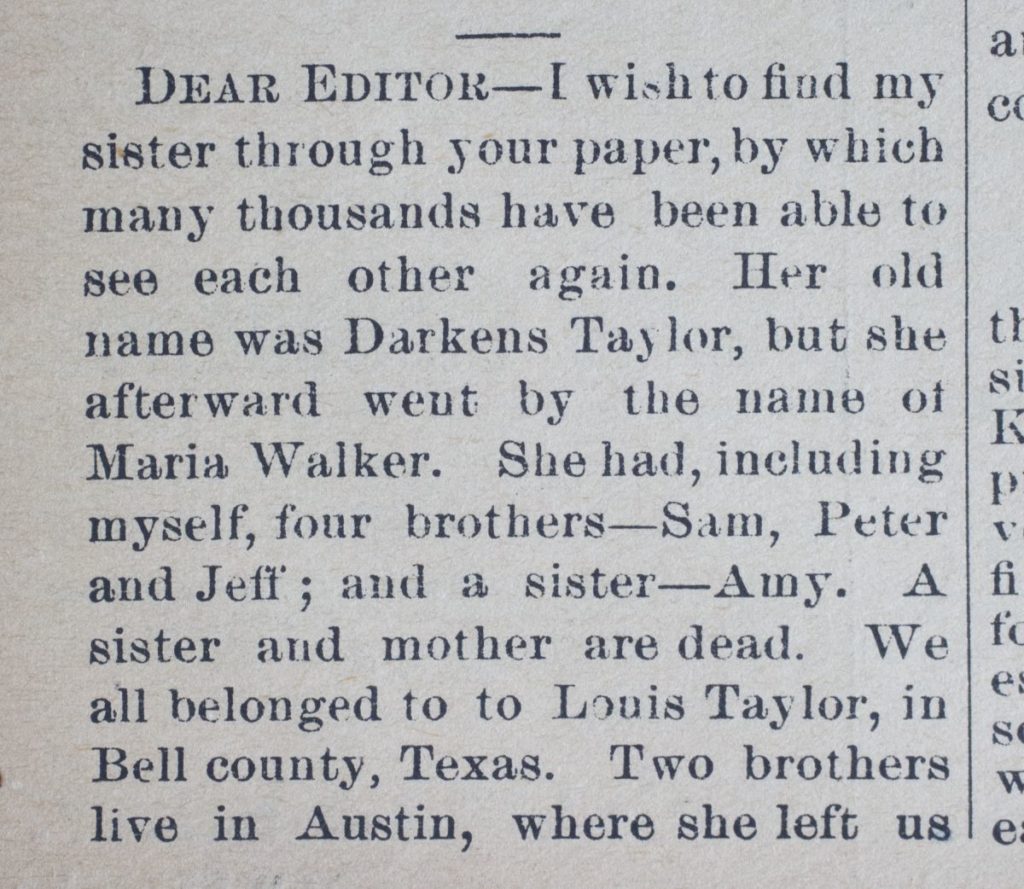

This past October, associate professor of African American Studies, Ruha Benjamin presented on their new book, “Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code” and sat in conversation with author and data scientist, Cathy O’Neil. Who is perhaps most well known for their 2016 bestseller, “Weapons of Math Destruction”.

The presentation and discussion, held at Housing Works Bookstore in SoHo, centered on “algorithmic bias” an issue of increasing recognition for scholars, researchers, and activists working at the intersections of social justice and technology. The most critical takeaway from this discussion, however might be the need to take a closer look at the assumption that that the technical and the social ever exist separately from one another. It’s this assumption; that technology is somehow a neutral space or apolitical artifact that Dr. Benjamin’s book works to dismantle.

The event began with D. Benjamin giving a short summary of their path into this research. She gave audience members three provocations to hold unto as she walked us through her conception of the “New Jim Code”. Based Michelle Alexander’s New Jim Crow, Dr Benjamin uses New Jim Code to describe the confluence of coded bias (our inherent bias built knowingly and unknowingly into the machine) and the supposed objectivity of technology (a mixture of beliefs that tech is a neutral tool without politics + the idea that the mathematical operates beyond or outside of the realm of the social); “ [New Jim Code is] innovation that enables containment but appears fairer than ‘more explicit’ forms of racialized bias that preceded it” (Benjamin 2019)

1.”Racism is Productive”

Here Dr. Benjamin pointed to the ways in which sociologists often think of race as “socially constructed”. This means that race and racism are not naturally occurring phenomena, but made, performed and informed by social norms. To a certain degree, particularly now that terms like “intersectionality” have become mainstream, the idea of race along with other vectors of power like gender, orientation and ability as socially constructed isn’t mind-blowing. But the idea of race being a thing that constructs as well as being constructed is.

“Racism produces things of value to some even as they wreak havoc on others” (Benjamin, 2019)

It should be no surprise then that new forms of racism, that are actually manifestations, expansions or iterations on previous forms come into being, particularly in and around technology.

2. “Race and Technology are Co-Constructed”

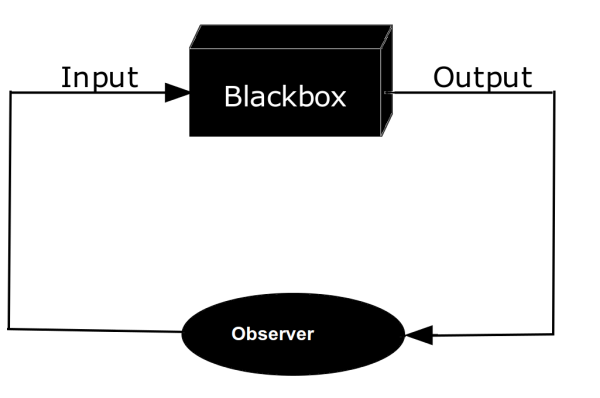

Through this provocation Dr. Benjamin asks the audience to consider the ways that race and technology shape one another and inform one another. Particularly within contemporary liberal “diversity” rhetoric, we are taught to think of racism as a mistake or aberration, a bug in the proper functioning of the system of Western society. But racism is not a bug in the machine, it’s part of the software. So we can’t only frame issues of bias in tech in terms of social “impacts”, what’s more critical is considering the social “inputs” that go unacknowledged but are also fed into the black box. Further these inputs “allow some inventions to appear inevitable and desirable.”

3. “Imagination is a Battleground”

Dr. Benjamin considers imagination a “contested field of action”. The scope of imagination delimits what forms of social and political relationships are possible, both for the oppressed and those contributing to and profiting from the oppression of others.

“Most people are forced to live inside someone else’s imagination” – (Benjamin & O’Neil 2019)

Thinking about the differentials of imagination. The places where we enter or be placed within another’s imagination are site where power operates, Any designed space fiction or other immersive narratives are living inside someone’s imagination as is living within a nation state, within an institution, inside any designed space or interaction. We might ask then who are the imagners

“The nightmares that many people are forced to endure are the underside of elite fantasies…Racism produces this fragmented imagination; misery for some and monopoly for others”

What does our fight for justice and liberation on the battleground of imagination look like? What does it mean for information professionals to be a part of this battle? For one, we must consider the way bias starts at the point of conceptualizing what problem exists that tech can then be consulted or created as solution to. This means looking at who is doing the imagining and how do the social norms and social fictions they have internalized inform what they can understand as “a problem to be fixed. Further our work has to involve not only critiquing and disassembling current systemic and systems of harm but also imagining and building the alternative worlds and futures we want to exist. Technology can potentially be a critical tool for that work, but that work must be approached through interrogating our own positions within the matrix of domination, and carried out with intention and with the most radical imaginings. I am reminded here of the speculative fiction collection, Octavia’s Brood, edited by community organizers Wahlidah Imarisha and Adrienne Marie Browne and named after the critically acclaimed matriarch of Black Speculative Fiction, Octavia Butler. The major thesis of the collection is the idea that all social justice work can and must be speculative work, because to organize towards liberation is to attempt building worlds that do not exist.

Abolition then entails not only bringing harmful systems to an end but imaging what we want to come next. By no coincidence, Dr. Benjamin quoted Octavia Butler during Q.A. when two audience members asked one for a timeline of community action around the battle for imagination in technology, while a follow up asked for more clarification on imagination as a call to action. or examples of what reclaiming imagination might look like and why it is important.

Dr. Benjamin clarifies that her call to imagination is meant to open it up as a space for theory and praxis. She warns that imagination as a productive tool or space can be co-opted by entities and for aims that want nothing to do with building actual alternatives to the status quo. Further, there is a limit to what imagination, on its own, can accomplish. But it must be part of the work.

In example, Dr. Benjamin firstly brings up a 2018 Stanford psychology study titled “The Numbers don’t Speak for Themselves”. The study hypothesis took up the idea that “rationality” could win over racism, if people we presented with the statistical evidence of systemic racism within the criminal justice system, they would have no logical choice but to accept it’s existence and support progressive policies that worked to undermine it. This data was presented to people living within the Bay Area, not exactly where one imagines secret racist nodes. But racism operates most violently and most insidiously in the banal and well meaning. According to Dr. Benjamin, what researchers found however was exposure to the data actually made their sample participants more likely to support stronger punitive measures not progressive reform. These findings run counter to the idea that more data draws an inevitable straight line toward social change. Something else is happening, or not happening, within the expanse between the data and transformative change. Some names for this space that were offered include Clauida Rankine’s “racial imaginary” or interpretive frames. People will fill this space, or take from this space the stories that work for the worldviews they already have. The data is not enough Dr.Benjamin’s call to imagination is a call for us to be “more rigorous” about this space.

“We have to become more deliberate and rigorous about this space in the middle. Whatever you want to call that; you can call it imagination, culture, lenses, frameworks whatever it is. But a lot of times we save our rigor and our investment for trying to produce the data. As if it’s gonna lead in some straightforward way towards to the changes what we hope [for].

I think we need to become not only more rigorous but more creative in shaping the stories, the interpretations and not accepting the dominant story about why people are kept in cages. That is exactly what an abolitionist imagination seeks to do. We have to work with that in a more deliberate way instead of hoping people will come to that on their own.” –

In attempting to define what the goal of abolitionist technologies are and what a liberatory imagination is, Dr Benjamin refers to herself as a student of Octavia Butler, paraphrasing her by saying “there’s nothing new under the sun, but there are other suns”. The liberative imagination then is about taking on the mantle of building worlds within worlds, models of what futures we want to exist.

Works Cited:

Benjamin, R & O’Neil, C. (2019, October). Race After Technology. Presentation and Pane Discussion at Housing Works Bookstore, New York, NY.