On September 14th, the Metropolitan New York Library Council (METRO) organized a tour, inviting professionals and students to look at Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM)’s Hamm Archives, located offsite in the neighborhood of Prospect Heights in Brooklyn.

After a roundtable introduction first by Davis Anderson, METRO’s Program Manager, and then by all attendees, Archives Manager Louie Fleck asked us to take a look at the archived materials that he pulled out and presented on the table. Each participant was asked to share a bit of our personal interest, whether archives, history, music or dance, and some questions about BAM or the archive, so that Louie could tailor the topics for the audience since there’s just so much to talk about.

BAM opened its door in 1861, first located in an opera house in Brooklyn Heights then at the current address, neighbor to the Atlantic Barclays Center, after a tragic fire in 1903. Although there’s always been an archive within the organization, significant evolvement of the archives department took place within the last twenty plus years. Other than the 1903 fire which took away all records, another major damaging event to the archive was a flood in 1967. Since 1995, seeing the urgency of preserving the organization’s 157 years of history, BAM has done much investment in the archive, from applying grants for processing physical materials, adopting and refining a digital database, to promoting engagement with the archive to researchers and the general public.

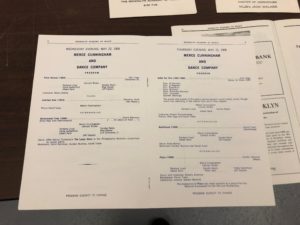

According to Fleck, the largest and most important project the archive has taken on so far is the Harvey Lichtenstein Presidents’ Records. Lichtenstein served as the President and Executive Producer of BAM from 1967 to 1999. During the remarkable 32-year leadership, he integrated modern dance to be a renowned part of BAM, despite that it is namely a music institute. Figures such as Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, and Alvin Ailey have stopped by BAM for multiple seasons of production. The materials resulted from the span of years range from administrative records, presidents’ files, and production records. It is not exaggerating to say that records in this collection cast light on not only the entire history of that 32 years of BAM, but also the performance history of American modern dance and music.

Supported by a major grant from the Leon Levy Foundation, the archivists at BAM felt fortunate and honorable to preserve the history. Fleck suggested that the Lichtenstein Records is so far the best cataloged collection: best in terms of the amount of materials digitized and the use of standard acid-free archival materials for all physical records. Materials are cataloged on folder or box level, and majority of the records can now be accessed online with a search function.

After a thorough research, the archivists at BAM decided on Collective Access to be their main repository. Collective Access is a free open-source software targeting arts and cultural organizations. The software gives its user large amount of flexibility in customizing their own database structure and vocabularies, and this is a prominent feature that attracted BAM’s archivists to Collective Access, in that they could construct a system almost from scratch and every single aspect will be tailored to their own cataloging needs. In fact, as Fleck said, since neither of the two full-time staff could program, a major amount of grant money did go to the salary of a programmer who did extensive configurations to reach the current state of the database. In addition, Collective Access encourages hosting organizations to not only set the archived content open, but also make the already-customized system, the skeleton of the database, downloadable for other organizations. This is another feature that sounds favorable to the archivists. With this attribute, smaller organizations with diverse programming could obtain the same database that BAM uses, a fact that the archivists added to the grant application, with the idea of virtual collaboration through the sharing of database structure. “This just fabulous to us. We didn’t want something that just benefits us, but something we created that could be for all,” said Fleck proudly.

The tour continued with a deep dive into exploring Collective Access. Fleck demonstrated structure of the database by showing the program’s backend to us. Year-Season-Production/Special Events is the spine of the information hierarchy. Productions are then categorized according to genre of arts: music, musical, opera, dance, etc. Each production is assigned a 5-digit production ID that will be added to every item under the production as an identifier. Special event includes artist talk, educational programs, fundraising galas and more. Fleck took an photograph item to show the differences yet between the backend and the online portal. At the backend, each photograph, other than basic information appearing on at front end such as title, date, photographer, subjects, and identifier, will also have size, a more detailed descriptive, special technique, and master status. As said, not all information is public yet, but researchers are encouraged to pay on-site visit to BAM’s archive, as many researchers have done so already.

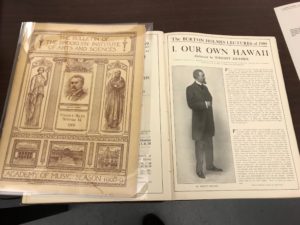

Seeing the abundance of materials collected here while thinking about recent event such as the devastating fire wiping out the National Museum of Brazil, one archivist in the tour group asked about if BAM’s archive has sought to retrieve information lost in either the 1903 fire or the 1967 flood. Since a large number of materials are ephemera/promotional papers that highly likely have had numerous copies, by crowdsourcing or through other means, the archive may be able to recover the history bit by bit. Fleck agreed on crowdsourcing as a good approach though never done, and mentioned about the collaborations with other Brooklyn cultural institutions. BAM was able to locate relevant materials from the archives of both Brooklyn Historical Society and Brooklyn Public Library. Moreover, BAM’s archivists had a seminar with collections of Brooklyn Museum. The collaboration later resulted in the form of BAM borrowing materials from the museum, digitizing them, and returning the objects along with the images to the museum. On the other hand, for years in 20th century, BAM was under the umbrella organization – Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (BIAS) – which included three other institutions: Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn Botanical Garden, and Brooklyn Children’s Museum. Through collaborating with these institutions for the archive of BIAS, BAM was also able to discover additional materials that speak to the organization’s history.

For an signature organization then and now like the Brooklyn Academy of Music, comprehensiveness of the preservation project not only benefits the organization itself but the larger arts community of Brooklyn, and of New York City. The brief tour at BAM’s Hamm Archives kindles various issues, from heritage preservation, digital construct of an archive, to inter-organizational collaboration. To learn more about the archive, please find it here: http://levyarchive.bam.org/