Category: Sula

Observing the Leo Baeck Institute

The information space I chose to observe for this blog post is the Leo Baeck Institute (LBI), my workplace. The Institute is named after Leo Baeck, a Jewish Rabbi in Germany during the time of the Second World War and a survivor of Theresienstadt concentration camp. Its mission is preserving the vast collection of documents, books, and artworks created by and describing the history of German-speaking Jewish people. Housed in the Center for Jewish History, LBI is one of five partner organizations that contribute to the expansion of access to Jewish history and culture. My job at LBI is to physically process books to be added to our searchable collections and then page those books when requested for the reading room. I often get to work with many different people as my job goes through different parts of the museum.

I sat down one day and made notes about the exchange of information going on in the Institute. Not only do I interact daily with my coworkers to complete tasks and learn new parts of my job, but I also watched how LBI workers interact with visitors and teach them about our mission. As a reasonably small office, there are very few formal communication procedures between employees. Generally, if we must get in touch with someone that is not only a few desks away, we make use of email. Usually, though, we can walk over and talk in person about a specific book or database question.

On a typical day, LBI receives about five to ten requests for books to be paged to the reading room that the Center for Jewish History shares among its partner organizations. For patrons to receive the information they wish to research, they must call the material in Aeon, a workflow management software specifically for libraries. LBI’s website features a complete online collection of our holdings that patrons can browse. Once they find a book they are interested in, they make a request, and I get an email from the system telling me which volume to pull from the stacks. Once I retrieve that, I bring it down to the reading room, and the librarians there give it to the researcher. The process is straightforward, and the exchange of information is streamlined.

The Leo Baeck Institute is very privileged at the wealth of materials we have in our collections and available to researchers. As we are focused on German-Jewish history, the collections librarians must scrutinize the donations we receive to make sure they follow this subject matter. In the past, when we accepted a gift, the donor would give a whole stack of books, whether they had anything to do with us or not. The current librarians are much more critical of what we take in, but there is still a massive backlog of books waiting to be processed and cataloged.

Reflecting on our international theme, LBI has three branches spread out across the world. The Jewish Museum Berlin has access to duplicate copies of our microfilm collection. Over 4,500 microfilms are housed there, making LBI’s collections accessible to researchers at the heart of our topic. London and Jerusalem are also home to LBI centers, allowing our organization to maintain and deepen relations with scholars, Jewish Communities, and the wider public.

One of the things I find most interesting about LBI is the people I have met. Our volunteers are a great source of wisdom and information. Two of whom are in their 90s, they are very sharp still and come in about once a week to work on translating documents from Hebrew and German, as well as telling their own stories from their home countries. Every year the Institute takes on interns from Austria and Germany who come to New York to study. They translate documents from their original German and process other materials. I find it fascinating the way that their countries have dealt with the events of the Holocaust. One intern who hails from Austria is working on a project on how her country likes to gloss over Austrian participation in World War II and pretend they were only following Hitler’s orders. She uses LBI materials to prove her view that Austria did, indeed, have a hand in the construction of the Holocaust.

This project reminds me of Sharon Macdonald’s article, “Is ‘Difficult Heritage’ Still ‘Difficult’?” As a library whose materials deal with the perpetration of atrocities against a people, we must take extra care to adequately respect the subject matter while still being able to work around and with it every day. Though we represent the Jewish people who have been subjugated throughout history, LBI has actually very few people who belong to that population. This poses a question of not only diversity practices, but what to do when white people represent a religious and ethnic minority. In Jennifer Vinopal’s “The Quest For Diversity in Library Staffing: From Awareness to Action,” she explores the needs for diversity in library workplaces. According to the International Federation of Library Association’s IFLA/UNESCO Multicultural Library Manifesto, “libraries of all types should reflect, support and promote cultural and linguistic diversity at the international, national, and local levels, and thus work for cross-cultural dialogue and active citizenship.” Despite the fact that our mission is very close to this statement, LBI would be better prepared to genuinely serve its visitors by employing librarians from the community it aims to help.

Overall, the Leo Baeck Institute is a library that provides valuable cultural and historical knowledge to those seeking to research German-Jewish topics. Expanding on more than just WWII, LBI preserves the traditions and scholarship of Jewish communities.

Lego Series Play Workshop

As user experience design continues to be identified in almost all fields of media, technology, and architecture; it’s an investment to understand how this field works and the different ways users can be reached from other perspectives. Apps, formally referred to as applications, are used daily to help users achieve a sense of satisfaction depending on the app utilized. For example, they can simply help with setting reminders or keeping us close with loved ones. One aspect that most users aren’t familiar with, is the many ways apps are created from the ground up. According to Norman information and the beginning of design comes from the brain, “One of the challenges, that the brain does not work at all like a computer, also provides us with an opportunity: the possibility of new modes of interaction that allow us to take advantage of the complementary talents of humans and machines.” (Norman, 2008). Lego Series Play is a collaborative problem solving methods used for designing apps, buildings, and other areas of design. Lego Series Play is a design software that is used to help designers build with empathy, focus on user needs, fix problems, and allow opportunities for new designs. While attending this hands on event there were moments when I the designer felt a deep connection with my build and how the director was able to make myself achieve a deeper emotion and connection through my design.

To gain more of an understanding of what we were doing in this workshop Heidi Brant gave each student a pack of legos. Each pack had the same set of legos found within them. Her first instructions were to use the legos and build a bridge with only rule: to make sure that our hand would be able to go under the bridge we built. We then had to modify our bridge based on how we were feeling at that exact moment. Whether we were happy, curious, or intrigued by what was happening that day. On top of the last modification we had to modify the bridge again based on a division in life that we felt. Whether if it was being homesick, losing a friend, or losing a loved one. This allowed the designers to work and create with empathy to focus on users needs to fix problems and allow for opportunities of new designs. Based off of all the design modifications we did, we now had to collectively work as a group to create an app. We were given a blue base to build on using legos to describe what the app will do and what features it will have. “Wireframing: Sketch your project’s form and interface without focusing much, if at all, on content. Wireframes provides a good sense of how people may interact with your project, and they don’t require any programming. Additionally, there are also opportunities to talk about scope and feature creep (before the project is too far along)” (Jentery Sayers). Lego series play is a different type of wireframing and prototyping. It Isn’t technical, it’s a more physical approach, such as a sketch but instead you are building it out. You have a different visual representation or your app that you are making. For our last build there was a more focused approach into a specific setting for user experience design. Each group was given a task card, our group had to redesign the experience of air travel with small children. We first individually came up with our own ideas on what we could do to improve air travel and we all had a similar approaches. We thought about the aggravation that flyers get when a baby would cry or a child kicking the back seat. We came up with an approach of creating a daycare area for kids, where they would be watched and monitored by flight attendants. Inside of this daycare, children would be able to use different interactive play fields where they can pretend to be flying the plane that they are on at that time and view what’s happening from outside. These designs came from our own personal experiences, all focused around designing with empathy. This was my first time sitting in on a workshop for User Experience design. This opportunity gave me something that I myself as a designer will look forward to gaining more knowledge about this technique in my future design making. My takeaways from this workshop was designing comes from experience, what yourself and others have gone through. The Negatives that can come out of Lego Series Play can be designing for people who lack a sense of visual, how can you create surrounding their needs visually. I hope that through this workshop we learned how to deal with multisensory designs and better UX designing for blind, and deaf users. Lego Series Designing is on a kindergarten level in the USA compared to places in Asia and Europe. It’s fairly new so I’m curious to see where it goes in terms of influencing design in the US especially major cities.

Transforming Designers – A Review

I attended a panel discussion called Transforming Designers – Not Just Another Working Day. The idea behind the event was to reflect on how the role of designers is changing in modern contexts since designers are no longer limited to their studios and a wide range of organizations are now developing their in-house design teams. The event was part of a series organized in collaboration between the Service Design Drinks Milan and NYC Service Design Collective which are groups of volunteers who bring together service design academics, professionals and enthusiasts.

I had two big reasons why I was drawn to this event. Firstly, I decided to pursue graduate school in the field of design because I believed that public service delivery in my home country of Pakistan needed to be improved through the principles of human-centered service design. So I was curious to hear how service design had fared in the US especially in the public service domain. Secondly, since having started graduate school, I had begun to study the emerging issues of science, technology and society, such as issues of algorithmic bias, surveillance capitalism and digital labour. I had also recently attended a talk on AIGA’s Design Futures project which proposed the idea of ‘environment-centered design’ which is design driven by core values for good. I was pondering over whether these discussions that were happening in academia also resonated with the industry and whether they influenced the professional designers.

The panelists for the event were:

Joanne Weaver

President, The Joanne Weaver Group – UX / Product Design Recruitment

www.linkedin.com/in/joanneweaver

Adam Perlis

CEO, Academy Product Design Agency

www.linkedin.com/in/adamperlis

Mirco Pasqualini

VP & Global Head of Design, Originate

www.linkedin.com/in/mircopasqualini

Tim Reitzes

Design Lead at the NYC Civic Service Design Studio at Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity

www.linkedin.com/in/tim-reitzes-78810139

The discussion followed five main topics which the panelists addressed one by one.

Are designers leading?

The major consensus was that up until a few years ago designers would get pushed around by product and engineering but in the last few years however this has changed a lot in the last few years. Designers are increasingly being seen as change-makers and ‘internal consultants’. Firms have identified the value of their insight. Senior designers are now applying their concepts of design to the designing of organizations and processes. However, on the public administration end this is still harder to do because of bureaucratic red tape. The takeaway was that designers need to identify the value they can create beyond their skills of design and drive this change themselves.

Given the new roles of designers, what new design skills or areas of study are emerging?

“Design Strategist” is becoming a popular position that companies are hiring for. What they are looking for is basically a hybrid of UX researcher, digital strategist and information architect. A good reflection of this trend is that even McKinsey and Company are hiring for this position in their consulting teams. Voice Experience (VX) design is another upcoming skillset and position as voice interface and assistants become popular.

“Co-creation” is also a skill that’s being sought after, especially in the public service domain. All the panelists emphasized how valuable it is for a designer to know how to manage a co-creation process and how difficult it is to pull off. Adam Perlis gave the example of his company’s approach of trying to “be in bed” with the clients by working in their offices, pairing up with actual employees and shadowing and sharing the actual work. Tim Reitzes talked about the difficulties of convincing public service stakeholders of the value of co-creation.

Another point under discussion was that its a challenge for designers to apply for these new roles because of their legacy job titles. There was some consideration that designers should just give themselves the title they want based on the actual work they are doing. Joanne Weaver being the recruitment expert here suggested that designers can add subtitles to their resume but the actual title should remain the official one.

How do you measure the value of design?

All of the panelists agreed that this is a difficult question to answer in most circumstances. It’s the “white whale” of design, everyone is looking for the right answer but no one has figured it out. However, the general agreement was that KPIs are important and they should be chosen on a case-by-case basis. Some additional metrics may also be needed such as ‘how many opportunities did you create as a designer?’ or ‘how many minds did you open?’ with the focus being capturing the impact the designer has had.

Data & creativity – which drives what?

This is where I was most surprised by the position of the panelists. The question was in your design process, do you first start with your creativity and come up with some out-of-the-box concepts and then validate them using data or do you first use the data to find the biggest problems and then use your creativity to solve them? I expected the panelists to say that it’s a bit of both but they had a consensus that it was important to start with the data first. This is the most efficient or cost-effective way.

What is the role of ethics in design today?

All of the panelists agreed that it’s become very important for designers to understand and be aware of the ethical implications of the products they design. The panelists highlighted how technology is influencing our social fabric, there are dark UX patterns everywhere and attention is the new currency. The panelists urged designers to think and list out all possible unintended consequences of their design decisions and the long term sustainability of the solution. Adam Perlis made a point that often clients may push you away from fairness and transparency and that becomes a very difficult space to manage.

It was exciting to hear that the role of designers is expanding into areas of strategy and leadership. There was a palpable excitement in the room full of designers about the future of products with designers on the decision making table. It’s also quite empowering that the nature of this expansion of the role of designers largely lies in their own hands. Apart from that, it was also encouraging to find out that the industry professionals were also eager to think critically about the impact technology is having on our society and they acknowledged the severity of the major issues which need to be addressed.

Why more people should be critical of WhatsApp

One of the theses presented in the Pew Research Center’s report on the Future of the Internet is that by 2025 the Internet will become “invisible” and we will no longer think about “going online”. One clear example of how that has already happened is that of WhatsApp and how widely common it has become in Pakistan. Its ubiquity combined with the advent of 4G network coverage means people now expect to be instantly connected on WhatsApp and there’s no more “going online” as it runs in the background. Is this a good thing for everyone? For this field research, I tried to find people who have actively avoided using WhatsApp in order to understand if it can have any negative effects on its users. The findings show that some people have serious concerns with using WhatsApp but it has become increasingly difficult for them to avoid using it. The conclusion is that it’s important to be critical of the role WhatsApp plays in our public and private conversations.

This research involved four semi-structured interviews. All participants are current students or alumni of my former school. Participants were recruited through a social media group and shortlisted on the criteria that they must be smartphone users and they must have actively deleted or uninstalled WhatsApp from their phones. The goal for this research was to find answers to the following questions:

- Are there people who have deleted their WhatsApp accounts? What were the reasons that drove them to this point?

- What was it like for them to quit WhatsApp? What challenges did they face? How did they deal with those challenges?

- Did they go back to using WhatsApp? Why or why not?

The common reason why all four of my participants had deleted their WhatsApp accounts was because they didn’t want to be “accessible”. They felt that as long as they were active on WhatsApp, they were considered “always available for a chat”. However, the reasons for seeking a break from this constant availability varied according to each person’s context. One of the participants shared that she was struggling with social pressure and anxiety and in all of this WhatsApp became one of the triggers for her panic attacks. She could see a direct correlation between how anxious she felt and whether or not she was using WhatsApp. On the other hand, another participant felt that keeping up with the conversations on WhatsApp took away too much time from her. This manifested in the form of never having time left for her non-work interests and prevented her from finding the right work-life balance ultimately leading to resentment and stress.

“…I just don’t like being that accessible. Unread messages bother me, I have to reply immediately, otherwise I start feeling terrible…its just something that never ends” – M, one of the participants of this study

Despite having such serious concerns with using WhatsApp, none of the participants have been able to stay away from it for too long. In fact, all four of them now have a sporadic on-and-off relationship with WhatsApp wherein they uninstall it from their phones every few months and then eventually ending up coming back. This is primarily because it’s just become prevalent and necessary in professional settings. One of the participants detailed an incident when she was on her longest hiatus from WhatsApp for around three months but she had to make her account again because one of her professors was using it to communicate with her class! Another participant stated that it was needed to communicate with their international team at work. When asked why their team could not use any other tool for this communication, they said the culture of using WhatsApp was already built into their organization and it just wasn’t possible to convince everyone to stop using it.

All of the participants also talked about how they were pressured into coming back to WhatsApp by their family and friends. WhatsApp becomes the default place where people coordinate their social engagements and share links, files and photos with each other. Even though the participants tried to convert their connections to other solutions like Telegram which is a similar but less common app or websites like FileBin or Google Drive for file sharing or simply going back to email, these were not long-lasting solutions. Other people did not consider the ramifications of using WhatsApp serious enough to convert to these solutions. Consequently, the participants felt a difficult trade-off between their own privacy and peace of mind and keeping in touch with their social connections.

Nearing the end of the discussion, I asked each participant to think about what they would change in WhatsApp to make it easier to use for themselves. This led to some interesting ideas for potential features. The justification for each feature reflects the kind of problems the participants faced and underpins our conversation on the limitations of the app. Some of the most interesting feature ideas are listed below:

- “Ghost mode” – Travel through the app like a ghost so that you can peacefully access all of your conversations, media and documents which are saved on the app but no one should be able to see you online or message you;

- Archive forever – Archive a conversation or a group forever which means you will not see them in your immediate chat list but the person or the group on the other end will not know that you have archived them;

- One-on-one – Conversations work more like real life so, for instance, users are only able to send one text at a time and have to wait for the other person to respond before they can say something again;

- Chat requests – People have to send you a request if they want to be able to chat with you on WhatsApp, they can’t automatically message you when they have your number and you have the power to turn off requests.

This report highlights how the widespread use of WhatsApp and the way it is designed can negatively influence some of its users and contribute to anxiety and stress in their lives. It is, therefore, important that we adopt a critical view of using WhatsApp, becoming aware of its drawbacks, seeking people’s consent before we engage them on it and carefully considering whether it is the best platform for our next public or private conversation.

A Review of Pratt SI’s Alumni Panel

On October 14, I attended an Alumni Panel hosted by Pratt’s School of Information. The panel consisted of three recent graduates from the School, each in different roles in the information community. They were:

Carlos Acevedo, the Digital Asset Manager at The Jewish Museum

Kate Meizner, a UX Designer & Data Analyst at Google

Anna Murphy, an Upper School Librarian at the Berkeley Carroll School, an independent school in Park Slope.

ASIS&T @ Pratt, the Association for Information Science and Technology, put on the panel in conjunction with Professor Irene Lopatovska’s INFO 601 classes. It was mostly students from her class who filled the room, but there were several other School of Information students in attendance as well. In general, the panel had a very casual feel as it was a small audience in the same room our class is held. The panelists went down the line answering questions about their time as graduate students and their transition into their respective fields. This panel was set up as a way for current students to see how our predecessors have managed to gain careers after graduation and give advice to current students who may be worried or not sure where to go after their impending graduations.

Mr. Acevedo, who has done Digital Asset Management for the Jewish Museum for three and a half years now, began by saying that the first two years of his position were taken up by introducing a DAM system and the last year has been spent managing that system. His team is small and he is the only one managing the DAM on the team. Mostly, that makes Mr. Acecedo’s work independent but he does have a lot of cross-departmental meetings and works closely with the Director of Digital, JiaJia Fei. Ironically, he noted, his project management style is very analog for a position that is so technology-based. To organize himself, he uses a large whiteboard that he splits into different sections corresponding to different tasks he is doing on long and short term bases. Because he meets with so many people from different departments, he makes sure to use formal Google calendar invites to set up meeting times, but uses Slack for more informal communication. When asked what the most challenging part of this job is, Mr. Acevedo noted that there are many projects around the museum he knows he can tackle based on his knowledge of best practices, but often these are out of his control due to departmental lines, budgets, and the will of the Board of Directors. The most rewarding part is when he can solve problems around him that have seemingly impossible solutions.

For Kate Meizner, her position as a UX researcher is very different. She is constantly collaborating with the twelve others on her team, which changes every year and a half. She describes her job as a bit of chaos; her duties range from running two research studies at a time to interviewing customers to surveys, analyzing data, and coordinating team strategy. In the mornings before everyone goes about their tasks, her team does a morning stand-up so everyone can let their coworkers know what they are working on that day, what needs to be accomplished, and who needs to meet to get that done. It can be a challenging workflow, as often non-UX people are invited to make UX decisions. Ms. Meizner also noted the lack of a central project management tool. She utilizes Google Sheets frequently, as well as GoToMeeting which is a remote desktop program, Qualtrics surveys, Tableau, Python, and R. Some current projects are deciding what her team strategy will be for the next two and a half years and analyzing data visualization studies, which last from three weeks to a month. For her, the most challenging parts of her job are new teams which makes finding your place in an organization that is constantly changing difficult, as well as figuring out how to get things done. Yet the most rewarding parts are understanding how research propagates in products, hearing how her work helps others improve their own workdays, and especially when she gets to apply knowledge learned at Pratt.

Anna Murphy’s job is on the Library Science side of the School of Information. As a high school librarian, she has no typical day. Her work ranges from teaching short workshops to students, researching projects for teachers, and conducting an eighth-grade technology class. She is constantly working with children, being centrally located in the library. There is almost no one in the school Ms. Murphy does not work with, so communication is especially important. Many times proposals for projects or workshops are very casual, maybe even just a mention in the elevator, so Google Sheets and Trillo, a task management system, are essential to staying on top of every interaction. For her, the most challenging part of her job is having to advocate for the students first. As an independent school, there is a lot of bureaucracy. She feels she must often work backward from what reading is. However, the most rewarding part is when the students engage with the books she buys for them and feel comfortable in the space of the library.

One of our readings that I was reminded of during this event was John Gehner’s article “Libraries, Low-Income People, and Social Exclusion.“ Especially when Ms. Murphy was talking about how her students come from extremely diverse backgrounds, I felt she was exemplifying what the article says is part of the duty of librarians. Many children who have troubled home lives can find refuge in their school libraries. “Action 3: Remove Barriers that Alienate Socially Excluded Groups” is practiced by Ms. Murphy when she talked about making a comfortable space for her students. She makes sure to not judge them on whatever topic they are interested in, as well as buying books that will pique their interest. She practices “Action 4: Get Out of the Library and Get to Know People” by teaching the technology class, doing classroom visits, and coaching a sports team to nurture a relationship with students outside of the library bounds.

I saw elements of the “Design Justice” article in what Ms. Meizner spoke about. She noted that many times non-UX designers will be on her projects and they fail to see potential problems that she would as someone who takes everyone into consideration, rather than just the mainstream population. She talked about making sure to pay attention to how her work is influencing others, similar to design justice’s mantra of “how the design of objects and systems influences the distribution of risks, harms, and benefits among various groups of people.”

Overall, I found this panel to be extremely helpful in my path through graduate school. It is always reassuring to hear the stories of others who have come before. By hearing how these three graduates earned their degrees, how they obtained their jobs, and how they use their knowledge gained at Pratt Institute in their work every day.

Sources:

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. “Design Justice: towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice.” DRS2018: Catalyst, June 28, 2018. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2018.679.

Gehner, John. “Libraries, Low-Income People, and Social Exclusion.” Public Library Quarterly29, no. 1 (March 15, 2010): 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616840903562976.

From Visitors To Virtual Audiences: Digital Engagement and Learning In Museums- A Review of an EDEN Webinar

In October 2019 I observed a fascinating EDEN (European Distance and E-Learning Network) Webinar by lecturer Chiara Zuanni. Zuanni is an Assistant Professor in Digital Humanities at the Centre for Information Modelling – Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities at the University of Graz, with a PhD in Museology from the University of Manchester. Her research focuses on museums, digital media and data practices, and the creation of knowledge and its mediation. Zuanni’s most recent published work includes a piece titled “Why Exhibition Histories?” asks how past exhibits in museums can be digitally represented and preserved.

This webinar approached a timely topic with precision, although at times it felt like an introductory course rather than professional development for those already in the field.

Zuanni’s presentation focused on the digital tools and methods that can be used in museums and other heritage institutions to supplement and improve overall learning and education. She began by outlining the social and cultural values of a museum in a table that contradicted the original 101 course feeling. It was overwhelming and hard to absorb, especially when trying to listen at the same time.

Zuanni then went on to develop her thoughts on museum learning. She emphasized that museums were a place to experience and develop interests, yet exhibits were still being treated like window displays where patrons walk away having learned very little. Her example was a visitor survey where guests were asked to draw from memory certain exhibits. Many couldn’t recall accurate displays, or specific details.

Transitioning to her solutions for the problem of stale museum learning, Zuanni introduces the concept of participatory culture and how it plays into most of society. People want to interact with things, whether that be for information or entertainment. When doing so, visitors are more likely to absorb more and leave with a sense that their experience added something to the museum.

Zuanni’s main point in her lecture was that museums have to address visitor experience in order to properly address museum learning. She proposes that digital media is the new way of opening more doors for guests before they even arrive at the museum. A proper website with up to date information and relevant hot links will make the visitors pre-visit easier. Similarly, digital wayfinding will start patrons’ visits off smoothly.

Other examples of enhancing visitor engagement and learning included digital tools such as apps (ie. Brooklyn Museums’ Ask), communicating via social media to encourage conversations with the museum, and using online analytics to predict and react to how patrons use online tools.

Zuanni’s insights show how these modifications to visitor experiences appeal to wide groups, and that they can be more easily researched and understood for future modifications to programming and learning environments. Overall, she highlights a modern theory that the use of digital supplements will bring out new meanings of cultural heritage. This will, as a result, be more impactful on guests.

After observing this webinar, I believe that the addition of digital learning environments and visitor engagement tools will go beyond adding new meaning to exhibits and cultural heritage. These upgrades will allow museums to preserve their exhibits and visitor research for future endeavors.

By preserving exhibits researchers and others interested will be able to observe the information on display in its original dialogue. This may offer perspectives that can be contrasted with future exhibits or current events. Similarly, being able to preserve digital analytics on visitor interactions with the museum will allow museum staff to trace how the institution has changed over time. This will eventually, and hopefully, lead to careful predictions on where the museum should be headed in order to provide the most good for patrons.

Overall, Zuanni’s research, in my opinion, will lead museums into a new age where visitors feel as if they are part of the story being told. In a time when cultural heritage institutions struggle for attendance and funding, projects such as these will be a welcome boost to inspire active learning.

References

Cloonan, Michèle. “W(H)ITHER Preservation?” The Library Quarterly, vol. 71, no. 2, Apr. 2001, pp. 231–242., doi:10.1086/603262.

Dalbello, Marija. “Digital Cultural Heritage: Concepts, Projects, and Emerging Constructions of Heritage.” 2009.

Posner, Miriam. “What’s Next: The Radical, Unrealized Potential of Digital Humanities.” Miriam Posners Blog, 28 July 2015, http://miriamposner.com/blog/whats-next-the-radical-unrealized-potential-of-digital-humanities/.

Review on Big Data Debate: Big data destroys what means to be human

I watched a Big Data Debate held by the Cambridge Union posted on November 16, 2018, through its Youtube channel. The topic was “big data destroys what means to be human”. This 3V3 debate was very informative and offered me an excellent opportunity to hear the voices from people in different academic or industrial fields about how they think about the pros and cons of the big data and effects on the humanities.

On the proposition side, Jeremy Pitt, the professor of intelligent and self-organizing systems at Imperial College, gave a constructive speech, pointing out that big data facilitated lots of design choices to destroy things what meant to be human. Collecting and analyzing real-time data from people, the big companies would asymmetrically control the means of social coordination, peer production, and digital innovation with little public accountability and transparency. Therefore, it would lead to a global monopoly of just a few players and a few platforms dominating each aspect of social and commercial life. He asserted that in this way, big data destroyed humanities both collectively and individually. Surveillance capitalism emerged and reduced the opportunities for successful collective actions. For individuals, big data diminished human’s ability to create narratives, generate ideas and have unmodified emotions through the algorithms.

Pitt’s speech had many solid points on the current situation, the trend of using big data, and many threats under the emergence of big data. As the first speaker, he lay the foundation for the whole debate on this big data topic. His speech also reminded me of Keller and Neufeld’s book, “Terms of service: understanding our role in the world of big data”, which narrated a world profoundly influenced by the big data. If people shared their data and lived permanently on the grid, they would lose the right to tell their own story. It is terrifying to me, because when everyone in the world agrees to live in a world that uses data to define people, I will have no choice to be a human I want to be.

However, Harry Ellison-Wright, the third-year student from Claire College, disagreed that big data would drive us to that world. He declared that big data would not destroy what meant to be human, but showed people what it meant to be human. Moreover, there were lots of beneficial example of using big data, such as cavendish laboratory, invented vaccinations to save thousands of lives. Even though someone used big data to quantify human’s greed, lust, envy, prejudice, addictions, and darkest secrets, big data actually demonstrated people’s shortcomings and deepened people’s understanding of themselves.

Then, Angus Groom from the proposition side who had a background in economics at Trinity College pointed out that something human owned for a very long time but now under the threats of big data, such as relying on our brains. Then he reemphasized that using computers instead of brains would finally treat privacy, power, and politics. To against Angus, Vesselin Popov, who studied human online behavior and psychological assessment in Cambridge, declared that we need to use big data and also employ precautionary principles. The problems the proposition side accused onto the big data actually were caused by the lack of education, the ability to scrutinize the monopolies, and the regulations on the big institutions to exploit people’s vulnerability. Vesselin claimed that big data did not take away our opportunities to make collective actions. Moreover, e-voting platforms even brought political power to people at a lower level or grassroots level, not only the elites.

After the floor speech provided various examples against each other, Joy Jia, a law student at Queen’s College, and Ken Cukier, a technology editor, had a final round. Joy strongly asserted big data could not be separated from its uses, and big data was valuable did not mean it was harmless. When big data offered people convenience, it also destroyed many vital parts in humanity, especially the emotion. Taking out the emotion out of the decision-making process, the existence of big data impeded human to self-determine, which harmed humanity fundamentally. In contrast, Ken stood for big data was, in fact, a product of our humanity and facilitated us to see further, learn the patterns of the world, and save the world. Also, he disagreed that big data made the power concentrated, because we lived in a world that everything was becoming concentrated.

This debate ended, but the discussion on big data still exists. When we think about the opportunities and challenges from big data historically and broadly, we can find big data is just another turning point in human evolution that our lives have changed dramatically. I agree that “humanity” will develop with social movements. How people behave and think is primarily depended on our resources and limitations. We cannot deny that we are so limited that we need technology to help us live in this world, and big data is one of the most powerful ones that human created to empower ourselves and improve our society. Also, I admit that any superpower can induce the dark sides of human nature, but people should never give up the chance to make the world better because of the potential risks. What we should do is not blaming how big data destroy what means to be human, but finding solutions to protect our humanity.

One floor speaker raised the example of the gun debate, whether it’s the guns that kill people or people kill people. I think this example can lead us to a solution that we should set regulations and make laws on big data issues, just as what we did for the gun. Specifically, to relieve people’s most worrying about the privacy, biased data, and asymmetric control of big companies, one possible solution could be increasing the data transparency that people can decide whether they want their data to be used and learn how their data are used. In my perspective, the most fundamental humanity that can not be destroyed is the freedom to know and choose. In this case, big data technology needs to be encouraged to make more contributions.

Reference

- Big Data Debate, Cambridge Union. Nov, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b3Uw1iu6xaA.

- Michael Keller and Josh Neufeld, Terms of service: understanding our role in the world of big data. Oct. 30, 2014. http://projects.aljazeera.com/2014/terms-of-service/#1.

Algorithmic Awareness as Activism

As part of the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Digital Scholarship Section (DSS) Open Data Week 2019, I participated in an open research discussion group: “Open Data Activism in Search of Algorithmic Transparency: Algorithmic Awareness in Practice,” led by Montana State University (MSU) researchers: professor Jason Clark and research assistant Julian Kaptanian.

At the time of the discussion, Clark and Kaptanian were in the process of concluding an IMLS-grant-funded research project entitled “Unpacking the Algorithms That Shape User Experience.” The ACLR DSS presentation built off modules and workshops that Clark and Kaptanian had run in the past year as part of the IMLS research project, exploring how building user competencies and empowering technology users on a personal level is a form of activism. You can learn more about the grant project here.

A ‘Symptom’ of Technology

Clark and Kaptanian grounded the discussion by characterizing algorithms as a ‘symptom’ of routine technology use. Like a cough to a cold, algorithms can be the less than desirable phenomena that shadows the data generated from our daily computer-mediated transactions. However seemingly inexplicable, algorithms have real consequences.

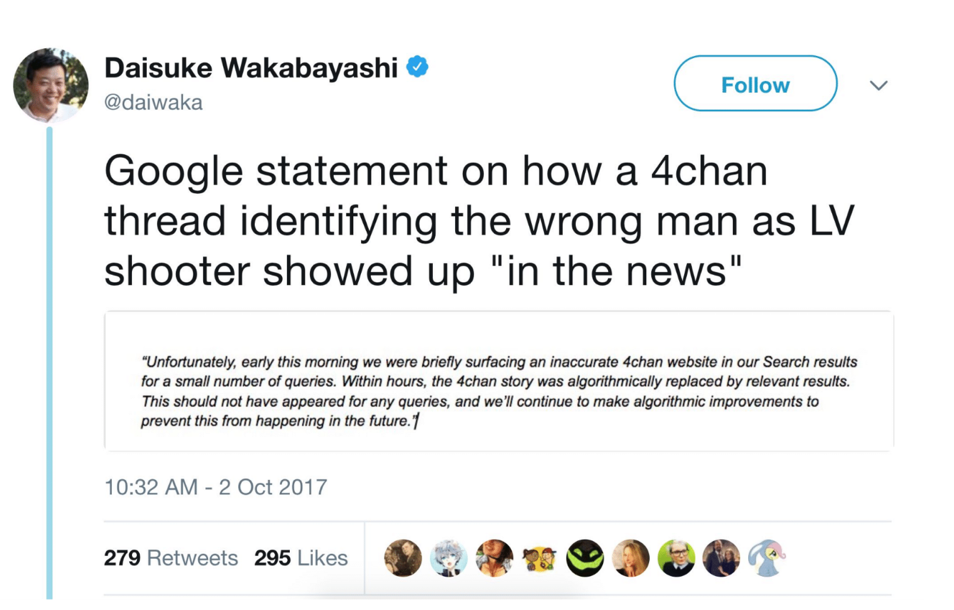

To illustrate this point, Clark recounted how online platforms amplified the incorrect online identification of the Las Vegas shooter in 2017 by pushing 4chan reddit users conspiracy theories in the online search results following the mass shooting. Within hours, an innocent man faced online harassment and blacklisting, an ordeal to which Google and Facebook simply responded ‘the algorithm did it,’ begging the question: what’s behind an algorithm? (Figure 1.)

Clark defines algorithms as the “computational processes embedded into our software” that in turn “predict, recommend, and speculate about our interests” in our all digital interactions. This is to considerable effect and risk as Gillespie warns in “The Relevance of Algorithms,” “as we have embraced computational tools as our primary media of expression, and have made not just mathematics but all information digital, we are subjecting human discourse and knowledge to these procedural logics that undergird all computation.” (Gillespie, 2014, p. 168) Clark then asks what if the “ghost in the machine” was understood by technology users and an “interrogation of algorithms” was a fundamental element of the digital environment? (p. 169)

Open Data and Algorithmic Awareness

Clark grounds this call to action in the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) “right to explanation” or “meaningful information about the logic involved” in an algorithmic decision. Clark posits GDPR is an international opportunity to demand algorithmic transparency and therefore positions digital literacy as a form of activism.

Clark and Kaptanian led a series of “algorithmic awareness” exercises that they piloted with MSU undergraduate students. First, they broke down the core functions of an algorithm including searching, filtering, ranking, and parsing information through illustrating the “weighted graph” of how Facebook ranks your connections online which in turn shapes your Facebook feed, a theoretical concept which is readily understandable to a user of social media.

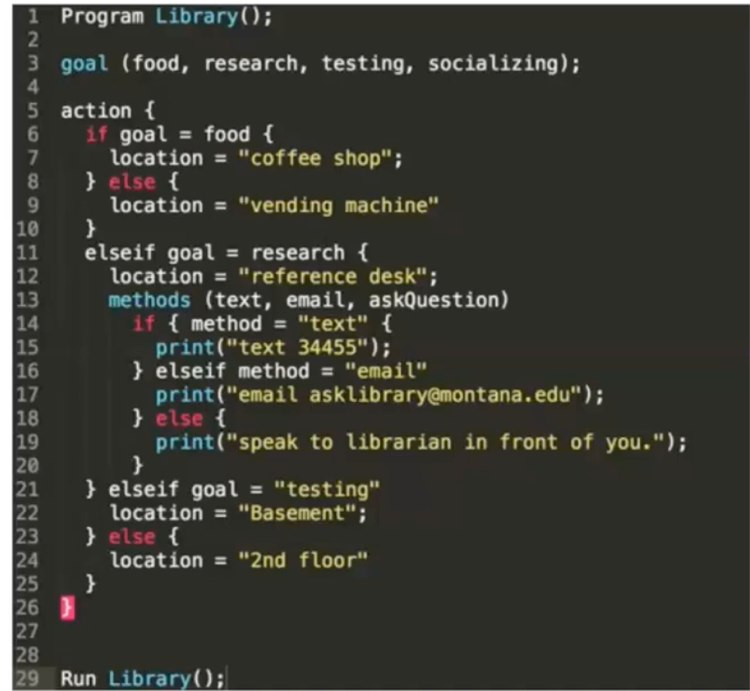

In the next exercise, Clark and Kaptanian aim to demystify the technical aspects of the algorithm by utilizing ‘pseudocode’ through which participants are asked ‘program the library’ or code different goals with the possible actions within a library to reach those goals. For example, the goal of ‘research’ could be achieved by the possible actions: ‘reference desk’ and ‘computer lab.’ They also introduced ‘methods’ as an added layer for achieving the task, like ‘emailing a librarian,’ as a tangible approach to the if, and, or logic underlying all code (Figure 2).

Despite the moderator’s best efforts to explain the technical structure of code through the tangible and familiar spaces of the university library, the exercise in practice proved difficult for the participants, requiring double the time to complete than the suggest 5-7 minutes. However, it was the follow-up questions to the exercise that proved the most valuable in understanding the limitations or code. Kapitanian asked the group who we envisioned as our audience in generating our code and we all answered differently. Some participants envisioned students, other’s faculty, staff or even an outside visitor. Collectively we came to discuss, however bound by brackets and formulaic syntax, our ‘code’ was still limited by our embodied experience enacted within social structures. Therefore, despite their neutral appearance, algorithms and the information they retrieve are subjective (Bates, 2006, p. 11-12).

The presentation concluded with a brief discussion of data profiling, and the steps users can take to understand what personal data is stored in platforms like Facebook and Google by walking participants through how to view and download their digital profiles. For many in the discussion, this exercise was nothing new and limited because their Ad Personalization feature in Google was already turned off.

‘Pedagogy for an Algorithm’

Moreover, the discussion “Open Data Activism in Search of Algorithmic Transparency: Algorithmic Awareness in Practice,” both highlighted the urgent need to build algorithms awareness into digital literacy efforts and while offering tools for educators and students to build that competences and ultimately framing that as activism.

The survey circulated at the close of the event, further emphasized these points. The survey solicited the level of resources and education around algorithm awareness at my current institution as well as asked at what grade level I thought it appropriate to introduce digital literacy.

My response: elementary school, or as soon as students begin to start to seriously engage with the internet.

At a moment when society is attempting to take a step back to fully understand the ‘ghost in the machine,’ it is important to see the opportunity in building digital literacy as a safeguard against current risks and advocate for change or open data in the future.

Works Cited

Bates, M. J. (2006). “Fundamental forms of information.” Journal of the American Society for Information and Technology 57(8): 1033–1045. https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/bates/articles/NatRep_info_11m_050514.html

Gillespie T. (2014), “The relevance of algorithms” in Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, eds. T. Gillespie, P. Boczkowski, and K. Foot. Cambridge: MIT Press, 167–194. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Gillespie_2014_The-Relevance-of-Algorithms.pdf

Figures Cited

Figure 1.

Wakabayshi, Daisuke (@daiwaka). “Google statement on how 4chan thread identifying the wrong man as the shooter showed up “in the news.” October 2, 2017, 10:32 AM, Tweet.

Figure 2.

Clark, Jason, 2019, Github algorithmic awareness pseudocode template. https://github.com/jasonclark/algorithmic-awareness/blob/master/modules/one/library-pseudocode-exercise-template.py