Tag: Person Place Thing

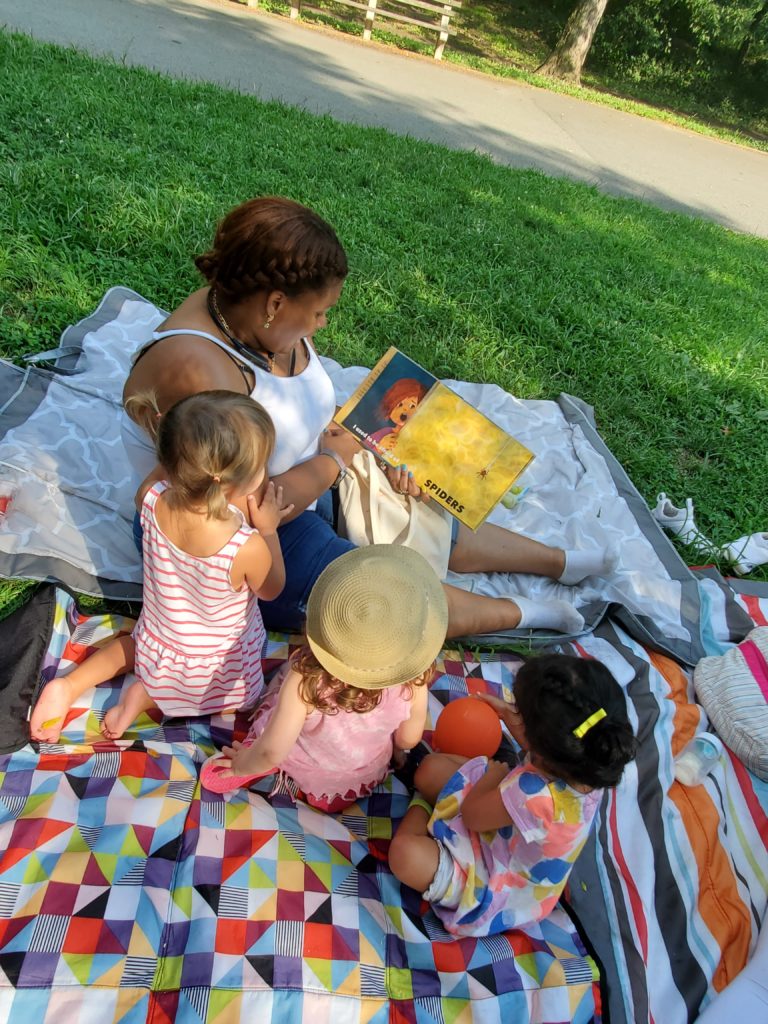

A nanny, in the home, bearing knowledge

I currently work as a nanny on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. My employers are white-collar workers, committed to their careers and to their children. Like many white-collar workers in NYC, they are not from New York, and their parents do not live in the city. In this role, I have participated in a hidden network of labor and information.

Person: Nanny

This job has revealed to me an entire system of labor that is hidden in many ways. As Downey (2014) discusses in the context of information and technology work, the work that nannies do is underrepresented by employers. It is common for nannies to work “off the books,” meaning that the income is not reported to the IRS and nannies and employers can avoid paying taxes. There are many reasons for nannies to want to remain hidden: immigration status, loss of public benefits, more take-home pay, etc. As a result, many nannies work outside of labor laws like minimum wage, overtime, and sick days.

Because there are few standards, there are a lot of nannies who are working for very little money. A nanny that I know, who is currently looking for work recently said to me, “a nanny’s worst enemy is another nanny,” describing the low salary offers that nannies are given. As Dwoskin, Whalen and Cabato (2019) discuss concerning content moderators in the Philippines, someone who is desperate may take a job with low pay because she needs the job. That makes it hard for other nannies to negotiate a better, commensurate salary. There are domestic workers unions and there is now a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in NY State that might aid in this problem of labor exploitation. Personally, I do not know any nannies that are members of the unions or who bring up the bill of rights to their employers. In many cases, nannies would be uncomfortable to bring this up for fear of losing their job.

The work of nannies is also hidden because raising children is not typical work. Nannies do social, emotional, logistical, and educational labor in addition to physical labor. This work continues even when we are not physically at work.

Place: Household

The household is the physical workplace of a nanny. Working in the home immediately creates an intimate setting for the employee/employer relationship. I see my employers in their pajamas, I know their good and bad habits, etc. This intimacy brings a nanny into the family, which can be good and sometimes it is messy. A family member is happy to do favors, doesn’t mind when you are running late, and will answer your calls and messages after work hours. An employee, however, should be compensated for all the previously mentioned work, in addition to their salary.

In this dynamic, the white-collar workers are entrenched in their careers and outsource the labor of home and child care to their nannies. While nannies are ostensibly being paid to care for the children, they are also caring for the parents in the chores that they do and the emotional labor of maintaining the home as a familial space. Nannies are often responsible for deciding purchases, cooking meals, supplementing love and support, and constructing family.

Thing: Child-rearing knowledge

In the case of career nannies, as they approach retirement, they will have raised upwards of 20 children in their careers. With this experience, and perhaps the experience of raising their own children, nannies bring a wealth of knowledge to their jobs. For first-time parents, it is often the case that they have no clue where to start to be parents. Parenting is not something that we can study in school, and having children is obviously independent of one’s ability and knowledge of parenting. Sleep training, potty training, learning to read, etc. can be intimidating to parents, but are essential to the growth of the child, and with their experience, nannies often take on these responsibilities. Nannies construct household systems in addition to relaying knowledge and skills to their employers. These household systems include children’s daily routines, nutrition, sleeping schedules, and housekeeping maintenance.

Nannies bring traditional knowledge from their own cultures into the families that they work for. The nannies that work in my building are from all over the world, bringing with them their culture. From home remedies, to old wives’ tales, to cultural values, to folk songs and stories, this cultural knowledge is passed to the children, who then teach it to their parents. For non-native New Yorkers like my employers, they live away from their families and don’t have regular support or cultural knowledge from their parents.

A nanny’s knowledge of raising children is unmistakably valuable. However, this value is not reflected in the status, rights, salaries that nannies receive. This recalls the questions from the beginning of the semester from Bates (2016) and Buckland (1991): “what is information?” and “who gets to decide what information is?” Cultural knowledge and personal experience are not valued as information. Children-rearing is seen in American culture as women’s work, which is still undervalued in society. In addition, the emotional work and knowledge of raising children is difficult to measure, making it less valuable in the eyes of capital.

Resources:

Bates, M. J. (2006). Fundamental forms of information. Journal of the American Society for Information and Technology, 57(8), 1033-1045.

Buckland, M. (1991). Information as Thing. Journal of the American Society for Information Science. Jun1991, 42(5), 351-360.

Downey, G. J. (2014). Making media work: time, space, identity, and labor in the analysis of information and communication infrastructures. Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society. Cambridge: MIT Press, 141-165.

Dworskin, E., Whalen, J. & Cabato, R. (2019) Content moderators at YouTube, Facebook and Twitter see the worst of the web – and suffer silently. Washington Post, July 25, 2019.

Domestic Workers United. http://www.domesticworkersunited.org/index.php/en/

Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, New York State Department of Labor. https://labor.ny.gov/legal/domestic-workers-bill-of-rights.shtm

Person, Place, Thing- Dr. Rabina

Person: Iddris Sandu

Iddris Sandu is a 22-year-old architectural technologist entrepreneur paving his own way in the field of technology. Raised in South Central Los Angeles, technology always sparked his interest as a child. At the age of 8 years old, while visiting his home country of Accra, Ghana with his family, his father abandoned him in the village and returned to the States with his passport. Abandoned for almost 9 months, he was finally able to get in contact with a non-governmental organization that was able to assist him in returning back home.

Upon his arrival back to the States the first iPhone had just been released. So inspired by the iPhone and the possibilities of what it could do, he began teaching himself every program language. For the next 2 years he spent most of his time at the Torrance Public Library, teaching himself how to code in C#, JavaScript, and Python. While checking out books in 2011, a Google designer noticed him and offered him an internship with the company. At 13 years old he was contributing to the development of Google’s social network.

Sandu created an app for his high school that provided students with navigation directions to their classrooms at only 15 years old. The application received a great amount of notice, including President Barack Obama. Sandu was invited to the White House to meet Obama and was presented with a commendation certificate. He then wrote an algorithm that he would eventually sell to Instagram and began consulting for Snapchat by the time he was 18. At 19, he worked for his last major company, Uber, where he developed a collision detection interface for the autonomous vehicle program. After his work for Uber, he stopped working for major companies to focus on work that would impact kids that looked like him and create accessibility that would increase diversity in the field of technology. His mission since then has been to bridge the gap between the informed and uninformed.

Sandu has also been focusing on merging hip hop culture and technology. His most notable work has been in the collaboration of the Marathon Clothing store with late rapper, Nispsey Hussle, which is also the world’s first smart store. He created the iOS app that enables visitors to unreleased music and video content by scanning the pictures on items of clothing, unlocking augmented reality experiences. The store received much acclaim from other big names in hip hop such as Kanye West, Jay-Z, and Jaden Smith and is currently collaborating on projects with them.

Place: Museum of the Moving Image

The Museum of the Moving Image is an institution which expands the appreciation and understanding of art, history, technique, and technology of film, television, and digital media. The museum collects and preserves moving-image relation artifacts while presenting exhibitions along with education and interpretive programs. The exhibits encompass notable audio and visual elements that are designed to assist the public in grasping the history of the industry and comprehension on its evolvement.

Located in the Astoria neighborhood of Queens, New York, the institution was originally opened in 1988 as the American Museum of the Moving Image. It underwent an expansion in March of 2008 and reopened in January 2011. The museum is so remarkable due it being the country’s only museum that is devoted in the preservation and exhibition of the “moving image” in all its forms. The Museum screens more than 400 films each year, ranging from a diverse mix of classic and contemporary films. Many public panel discussions also take place at the museum such as the Pinewood Dialogues, which is a continuous series of conversations with the creative professionals in film, television, and digital media. Also maintaining the nation’s largest and extremely comprehensive collection of artifacts in relation to the moving image, the museum holds a great amount of pivotal history amounting to over 130,000 artifacts from every stage of producing, promoting and exhibiting motion pictures, television, and digital media.

The institution holds many noteworthy exhibitions each year that receive great acclaim. The Breaking Bad exhibit creates access to the props, costumes, schemes, more behind-the-scenes material that contribute to the transformation of Walter White. The Magnificent Obsessions exhibition showcases the little pieces that contribute to the bigger picture, such as set design and actor’s research. For example, the exhibit displays the notes of the production designer from Catch Me If You Can. The museum also has a theater which is one of its main attraction. Seating 267 people, it features classic films, filmmaker interviews, and live events.

Thing: Levi’s Smart Jacket

A collaboration between Google and Levi is resulting in a line of tech-infused denim jackets. The Levi’s Trucker Jacket was originally released in 2017 but now features Google’s Jacquard technology, making some notable upgrades. The tech features are installed on a now smaller Bluetooth-enabled tag that acts as a touchpad. Clipped into the jacket’s let cuff, one can control their applications by swiping on it. One is capable of setting which apps you want to function with different gestures: a swipe up, swipe down, double tap, and cover. Jacquard has also been upgraded to be compatible with more apps. Utilizing the gestures, one is able to take a selfie from their cellular device, overlook their calendar and traffic conditions, and activate Google Assistant. There is also an “Always Together” feature which alerts you if become separated from your phone while wearing the jacket. The jacket has all these tech features while being fully washable.

Unlike the original jacket, cost is significantly lower due to the Jacquard Bluetooth. The original jackets had touch-sensitive Jacquard threads weaved into the sleeve itself which made them costlier. The new and improved jackets are created normally and are then inserted with a small Jacquard fabric weave inside the cuff of the sleeve. Initially costing $350, the cost dropped to $198 for the standard jacket, and $248 for the Sherpa Jacket, which included insulation for weather. The only difference physically between the originals and the new jackets are the left cuff being a tad stiffer due to there still being some electronics in there despite Jacquard being able to work with touch sensitive threads.

Sources:

About. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://movingimage.us/about/.

Bell, K. (2019, September 30). Google and Levi’s introduce a new smart jacket that can answer calls and snap selfies. Retrieved from https://mashable.com/article/google-levis-jacquard-trucker-jacket/.

Bohn, D. (2019, September 30). Google’s Project Jacquard is available on new Levi’s jackets. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2019/9/30/20888909/google-levi-project-jacquard-available-trucker-sherpa-jackets-price-design.

Iddris Sandu is Going to Change the World. (2019, September 24). Retrieved from https://www.surfacemag.com/articles/iddris-sandu-is-going-to-change-the-world/.

LaScala, M. (2014, August 11). Why the Museum of the Moving Image is the Coolest Museum Ever. Retrieved from https://www.cntraveler.com/galleries/2013-09-12/photos-museum-of-the-moving-image-exhibits-queens-new-york.

Museum of the Moving Image. (2019, October 15). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Museum_of_the_Moving_Image.

Oteng, S., Oteng, S., & Oteng, S. (2018, December 23). Meet Iddris Sandu, who was once abandoned by parents’ in Ghana but now the brain behind Uber. Retrieved from https://ghnkomo.com/meet-iddris-sandu-who-was-once-abandoned-by-parents-in-ghana-but-now-the-brain-behind-uber/.

Ramalho, C. (2019, October 21). Iddris Sandu worked for Uber, Google and Kanye. Now he wants to fix tech’s diversity problem. Retrieved from https://www.wired.co.uk/article/iddris-sandu-tech-diversity.

R. Scott Smith, Villa Farnesina, Brooklyn Museum’s Ask App.

Person: R.Scott Smith

During my years as an undergraduate at the University of New Hampshire, I was unsure what I wanted to major in. I began taking courses that interested me, to see if it was something I wanted to study long term. My first two choices were art history and mythology.

When I walked into my mythology course that semester, a class that must have been over 40 students, I was handed a quiz that was intended to give the professor a better understanding of how much you knew about myths already. Amidst may serious questions, that I can hardly remember now, there was one question that stood out: “Who was the king of all Greek gods? A: Apollo, B: Hera, C: Zeus, D: Bill Clinton.”

It was because of Professor Smith’s mythology course that I graduated with a minor in classics, and why 2 years later I traveled abroad to Rome and Pompeii on a one week course he taught in conjunction with another Professor. He even wrote me a recommendation to get into my graduate program.

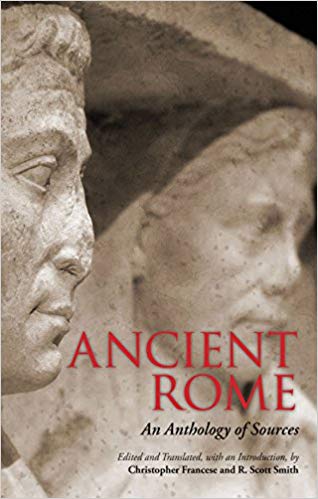

Professor Smith is not only a professor at the University of New Hampshire, but he also has a Ph.D. from the University of Illinois, and is an author with a plethora of publications. He has written many anthologies regarding myths, Ancient Rome, and translations from primary sources. At UNH he teaches classes on classical mythology, ancient Rome, hieroglyphs, Greek, Latin, and a course that reads only classical books in their original Latin. While teaching all of these courses and editing a book on Greek and Roman Mythography for Oxford University Press, he is also creating a digital platform called “Putting Greek Myth on the Map” which intends to show a relationship between mythical figures with real places.

One of Professor Smith’s publications is Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation. In this publication he and two others translated and anthologized over 50 texts. The authors include an appendix of evidence from Papri and Linear B tablets, as well as a thematic index, a mythological dictionary, and a genealogy.

Place: Villa Farnesina

While on my trip abroad in Rome, I was given an afternoon off to go see one of my favorite pieces of artwork: Raphael’s Cupid and Psyche Loggia. I credit this one visit as what inspired me to go into the Museum field.

If you research for your visit ahead of time, you will find the Villa’s website where you can learn the history of the building. Farnesina was built for Agostino Chigi by a pupil of Bramante. Inside you will find artworks by Raphael, Sebastiano del Piombo, Giulio Romano, and Il Sodoma. but it will also tell you that the Villa is located in Trastevere, a more suburban area of Rome just over the Tiber River. This location unfortunately makes it easy to miss, and I can tell you from experience that the Villa itself is very hidden. Still the Villa as a Museum is extraordinary.

I did not do any research before going, before the trip had even started, I wasn’t sure if I would find the time to go. I was fortunate enough to be on a trip that was already scheduled for me. One day, after spending the morning in the Jewish Ghetto of Rome, my professor told me it was alright to take off the afternoon and go see it. Since I hadn’t had the chance to plan, I ended up getting there with only an hour until closing because I had gotten lost, and on the wrong bus.

The Villa is beautiful and large, and ridiculously quiet. I’m not sure if it was because there were only a hand full of people inside, or if it was because of the state of awe everyone inside was in. The first room of the Villa is Raphael’s famous Galatea, larger than I expected, and much higher up the wall. I wish I had stayed longer, but I moved on quickly. The next room was the Psyche and Cupid Loggia. A Loggia is a ceiling, so the room was empty except for a few chairs so people could sit and look up at it. Everything you might’ve heard about it is true, the fruit looks like it is real and could fall right on you at any moment, the colors are as vibrant as if he had painted them yesterday. I spent a good half hour under the Loggia, amazed beyond believe and having trouble actually believing I was there. I was urged onto the next section of the Museum, which I passed through quickly, until I came to a section that described the restoration process on both the Galatea and the Psyche and Cupid pieces. From what I can remember the Museum show cased exactly how the restoration team took samples of the paints used in each fresco and how they recreated it. I had never before seen this side of art history that examined how painters created paint, or how it was applied. It was a scientific side I was obsessed with.

When I returned from my trip I excitedly told my advisor about the Villa, and about the exhibition on the restoration. When I went online and tried to find information on it, I found little to nothing. The Farnesina website details the restoration process focusing on keeping the artwork looking the way it looks, for example restoring the adhesion between the plaster and artwork. They quickly mention testing the “traditional materials” with CIR and “experimenting with new approaches and materials.” I was heartbroken that I wasted so much time staring at the piece, that I ran out of time for this interesting side of the Museum, and that I could not find much information about it later.

Being at the Villa Farnesina inspired me to want to work in restoration in museums, but on a much different side of it than taking a brush to the artwork myself. I want to study the artwork and figure out how they were made and how they can be fixed. I also want to work to make places like the Villa Farnesina more accessible to the people who can’t get there physically. Everyone should be able to experience their favorite artwork, even if they can’t fly to Rome.

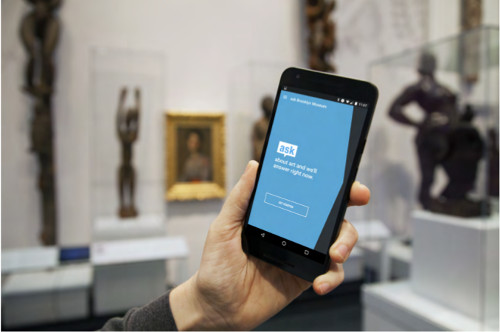

Thing: Brooklyn Museum’s Ask App

I am fortunate enough to be taking a class taught by Professor Devine, titled Museums and Digital Culture. Last week we had our class at the Brooklyn Museum, where Professor Devine is the Director of Visitor Experience and Engagement. We began the class with a presentation Professor Devine gives to investors and those interested about the app. It was created in three different phases. The first sent “Gallery Hosts” into certain exhibitions with vests telling visitors to ask them questions. The response was good, people would ask them questions about art, among other things. Phase two had “Gallery Hosts” in front of certain pieces of art, who would answer questions, but who would also hand out cards that showed visitors how to get to another piece of recommended art. This backfired, as most people wanted something more personalized than a preprinted card. Finally the last phase began, which is what inspired the Ask App. Ipods were given to members and select test groups upon entering the Museum with imessage that was sent to the Curator. With this phase the team was concerned the most with “screen suck” or that people would be too involved with their screens to actually look at art. They found that this wasn’t the case, especially when the curator could prompt visitors to look at specific pieces of the art he was describing.

From the third phase, the Ask App was born. Now, anyone who walks into the Brooklyn Museum can download it off of the App store, and speak to an art historian about art. During this class we were sent loose in the Museum to try it out, and I had a fantastic discussion with one of the team members about their Egyptian art exhibit. After this, we got to meet the team and see how the system worked.

While the only thing a visitor sees is a screen similar to imessage, the team sees a screen full of coded numbers asking them questions. One team member showed us how she would split her screen between the incoming conversations and the Brooklyn Museums Wiki, something she updated when no one was asking questions.

I had never been to the Brooklyn Museum before, but I couldn’t believe how fun it was to experience it with the Ask App. It’s a really cool tool to keep visitors interested that I believe all Museums should start to use. Not only does it get you to look at art closer, it also encourages you to see more of the Museum and stay engaged with it.

It’s Prof. Cooley, in the Art Library, with the Useless Box

Person: Heidi Cooley

My person is Heidi Cooley, author of Finding Augusta: Habits of Mobility and Governance in the Digital Era. I was at the 4th floor library at PMC looking at the new books display, and this book caught my attention. The title and the cover image conveyed the perfect combination of artsy, academic, and applying theory to practice. A brief skim of the chapters revealed that this book encapsulates perfectly the four degrees taught at the School of Information.

So what is Augusta? Scott Nixon, a traveling insurance agent from Augusta, Georgia, used a 16mm camera to document places in the U.S. called Augusta, filming from about 1930 to 1950. These are towns and streets and villages and storefronts and some other surprising Augustas. The result is an 18-minute movie, available on YouTube and archived, along with Nixon’s home movies, at the University of South Carolina (USC).

Cooley was a professor of technology and media arts at USC, and during a visit to the archive, the archivist showed her The Augustas and these 18 minutes triggered this book. The book is interesting, clever, and well written, but the main appeal to me is how Cooley extrapolated meanings and applications of information in ways that are both deep and broad and directly connect to our school. The Augustas relate to technology, mobility, mobile devices, bodies in motion, managing the movement of “stuff,” the application of surveillance, tracking, indexing information, metadata creation, digital and physical preservation, archiving, display, and the implication on governance.

Cooley’s departure point is the traveling salesman problem, which asks, “Given a list of cities and the distances between each pair of cities, what is the shortest possible route that visits each city and returns to the origin city?” It’s a question that is relevant to information storage, retrieval, design, display, usability, findability, and more. Books and articles that reflect the intellectual landscape in an interdisciplinary way are few and far between, and Cooley’s study is an “example of digital humanities scholarship and critical readings of the political stakes of new media technologies” (Archibald, 2016). It can provide new appreciation for a broad and deep understanding of information.

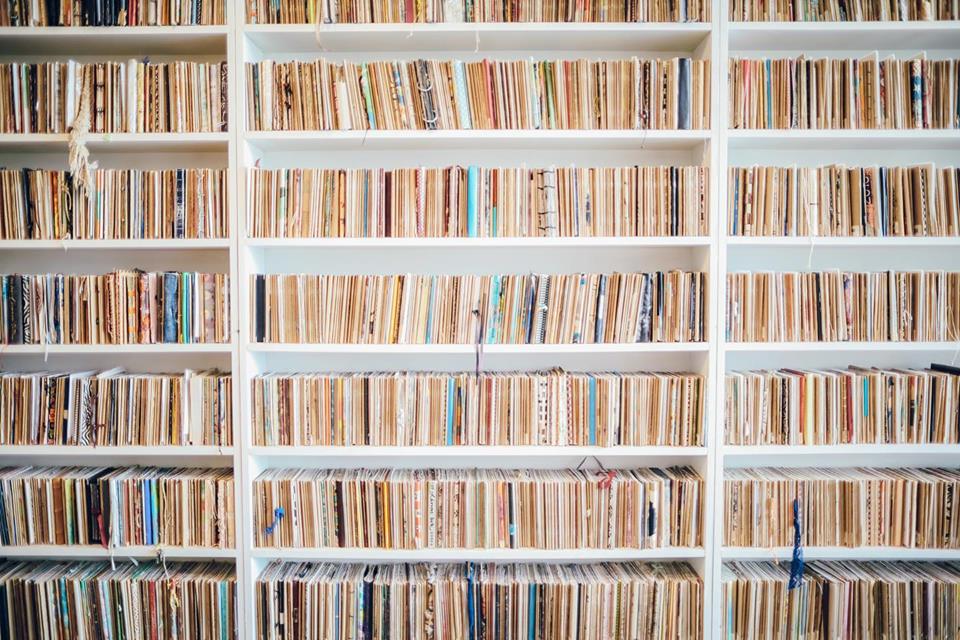

Place: Brooklyn Art Library – The Sketchbook Project

I’m not sure what possessed me to make my way across town on one of the coldest days of last winter to visit The Brooklyn Art Library. I must have read about it someplace, but I can’t recall where.

Nestled in some abandoned (or maybe it was the cold) side street in Williamsburg, the library is one large rectangular room lined with bookshelves, and on them are uniform sketchbooks. People buy a sketchbook from the library, then draw, paint, write, collage to their hearts’ delight, and bring or mail it back to the library. The library digitizes the books, adds metadata, and places them on the shelves where they are arranged chronologically. To look at a book, you register on your phone or using one of their iPads, and request up to three sketchbooks. You can search by artists, by title, by region, by topic, and more. You receive the book within a few minutes and as a special bonus receive the book immediately preceding the one you requested. This aspect of the arrangement particularly appealed to my knowledge organization sensibility. It somehow reminded my of Aby Warburg’s library in London and its cross-disciplinary references between adjacent sections.

The books themselves are, as one might expect, very wide ranging. Every imaginable kind and color of ink and pencil and paint and every style of drawing. There are journals and landscapes and manga and books in all languages and from many countries. Some are magnificent, some are puzzling, but the effect is quite strong, and even the duller ones are lifted up by being part of a beautiful and surprising collection.

Toward the back of the library there is a community-style conference table where visitors can look at the books. There were few people during my visit (temperatures were in their 20s, after all) but there were some, two adults and a child, some other adults of all ages. The people who work there are conversational without being pushy and will take their cues from the visitor.

The library embodies some of the ideas expressed in Finding Augusta, particularly those about arrangement of information as mobile objects; as Cooley notes, “mobility, its organization and potentiality, is the defining problem of this present” (Cooley, 2014). To that end, the Brooklyn Art Library provides its Bookmobile, which brings the collection to locations around the country in a mobile library.

Thing: The Useless Box

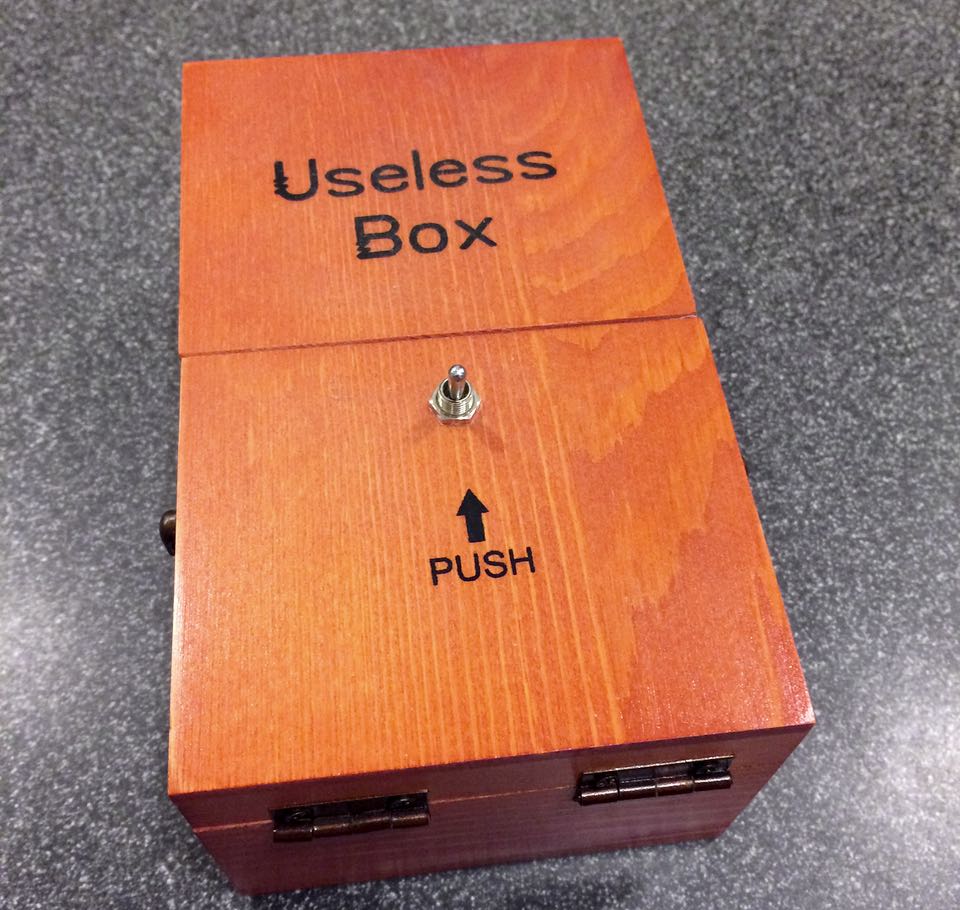

For my Thing, I chose a useless box. How do I know it’s a useless box? Well, it says so in bold black lettering on top of a flimsy looking plywood box: Useless Box.

Right under the lettering there is a slit in the cover, and below it, a simple mechanical switch. Push the switch and half cover lift open from the hinge to the center, only to immediately close again. Open close, open close—that’s all it does. Useless.

Measuring about six inches, I can hold it my hand, turn it around and examine it. Peeking inside I can see a small mechanical device operated by battery. Pushing the outside switch makes the top open and immediately close. The only use that comes to mind, or at least to my mind, it that this is some executive stress toy.

So what makes The Useless Box a worthy choice for my information-Thing? Well, it’s the legacy of the Useless Box that ties in to our information universe. Developed in the 1950s in Bell Labs, it is the brainchild of Claude Shannon, a pioneering information theorist:

“The first working model was constructed by his mentor, Claude Shannon, who later became known as the father of information theory. This context, the fact that the creators of this aggressively pointless gadget are emblematic figures in the ascendancy of machines over our contemporary world, lends a frisson of historical oddity to what is essentially an executive toy.”

(O’Connell, 2016)

Contemplating the box as an expression of meaning is an act of mediation that can take you in many directions, from the meaning of labor and mechanical objects to questioning usefulness itself. And finally I admit, one appealing thing about this Thing is that is reminds me of Thing. Picking up on some lines of thought from Cooley, this can take us to the latest in creating life out of dead brain tissue to Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” in which a woman learns how to see the future:

“From the beginning I knew my destination, and I chose my route accordingly. But am I working toward an extreme of joy, or of pain? Will I achieve a minimum, or a maximum?”

(Chiang, 2002)

In other words, even when everything is known (like a device that you know will close itself immediately after you open it), isn’t it still possible for wonder to exist?

by Debbie Rabina, Ph.D.

References

Archibald, R. (2016). Review of Cooley, Heidi Rae, Finding Augusta: Habits of mobility and governance in the digital era. H-War, H-Net Reviews. Retrieved from http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=43095

Chiang, T. (2002). Stories of your life and others. New York: Vintage.

Cooley, H. R. (2014). Finding Augusta: Habits of mobility and governance in the digital era. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press.

O’Connell, M. (2016) Letter of recommendation: The useless machine. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/04/magazine/letter-of-recommendation-the-useless-machine.html

Shaer, M. (2019). Scientists are giving dead brains new life. What could go wrong? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/02/magazine/dead-pig-brains-reanimation.htm