Author: Katie Drake

R. Scott Smith, Villa Farnesina, Brooklyn Museum’s Ask App.

Person: R.Scott Smith

During my years as an undergraduate at the University of New Hampshire, I was unsure what I wanted to major in. I began taking courses that interested me, to see if it was something I wanted to study long term. My first two choices were art history and mythology.

When I walked into my mythology course that semester, a class that must have been over 40 students, I was handed a quiz that was intended to give the professor a better understanding of how much you knew about myths already. Amidst may serious questions, that I can hardly remember now, there was one question that stood out: “Who was the king of all Greek gods? A: Apollo, B: Hera, C: Zeus, D: Bill Clinton.”

It was because of Professor Smith’s mythology course that I graduated with a minor in classics, and why 2 years later I traveled abroad to Rome and Pompeii on a one week course he taught in conjunction with another Professor. He even wrote me a recommendation to get into my graduate program.

Professor Smith is not only a professor at the University of New Hampshire, but he also has a Ph.D. from the University of Illinois, and is an author with a plethora of publications. He has written many anthologies regarding myths, Ancient Rome, and translations from primary sources. At UNH he teaches classes on classical mythology, ancient Rome, hieroglyphs, Greek, Latin, and a course that reads only classical books in their original Latin. While teaching all of these courses and editing a book on Greek and Roman Mythography for Oxford University Press, he is also creating a digital platform called “Putting Greek Myth on the Map” which intends to show a relationship between mythical figures with real places.

One of Professor Smith’s publications is Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation. In this publication he and two others translated and anthologized over 50 texts. The authors include an appendix of evidence from Papri and Linear B tablets, as well as a thematic index, a mythological dictionary, and a genealogy.

Place: Villa Farnesina

While on my trip abroad in Rome, I was given an afternoon off to go see one of my favorite pieces of artwork: Raphael’s Cupid and Psyche Loggia. I credit this one visit as what inspired me to go into the Museum field.

If you research for your visit ahead of time, you will find the Villa’s website where you can learn the history of the building. Farnesina was built for Agostino Chigi by a pupil of Bramante. Inside you will find artworks by Raphael, Sebastiano del Piombo, Giulio Romano, and Il Sodoma. but it will also tell you that the Villa is located in Trastevere, a more suburban area of Rome just over the Tiber River. This location unfortunately makes it easy to miss, and I can tell you from experience that the Villa itself is very hidden. Still the Villa as a Museum is extraordinary.

I did not do any research before going, before the trip had even started, I wasn’t sure if I would find the time to go. I was fortunate enough to be on a trip that was already scheduled for me. One day, after spending the morning in the Jewish Ghetto of Rome, my professor told me it was alright to take off the afternoon and go see it. Since I hadn’t had the chance to plan, I ended up getting there with only an hour until closing because I had gotten lost, and on the wrong bus.

The Villa is beautiful and large, and ridiculously quiet. I’m not sure if it was because there were only a hand full of people inside, or if it was because of the state of awe everyone inside was in. The first room of the Villa is Raphael’s famous Galatea, larger than I expected, and much higher up the wall. I wish I had stayed longer, but I moved on quickly. The next room was the Psyche and Cupid Loggia. A Loggia is a ceiling, so the room was empty except for a few chairs so people could sit and look up at it. Everything you might’ve heard about it is true, the fruit looks like it is real and could fall right on you at any moment, the colors are as vibrant as if he had painted them yesterday. I spent a good half hour under the Loggia, amazed beyond believe and having trouble actually believing I was there. I was urged onto the next section of the Museum, which I passed through quickly, until I came to a section that described the restoration process on both the Galatea and the Psyche and Cupid pieces. From what I can remember the Museum show cased exactly how the restoration team took samples of the paints used in each fresco and how they recreated it. I had never before seen this side of art history that examined how painters created paint, or how it was applied. It was a scientific side I was obsessed with.

When I returned from my trip I excitedly told my advisor about the Villa, and about the exhibition on the restoration. When I went online and tried to find information on it, I found little to nothing. The Farnesina website details the restoration process focusing on keeping the artwork looking the way it looks, for example restoring the adhesion between the plaster and artwork. They quickly mention testing the “traditional materials” with CIR and “experimenting with new approaches and materials.” I was heartbroken that I wasted so much time staring at the piece, that I ran out of time for this interesting side of the Museum, and that I could not find much information about it later.

Being at the Villa Farnesina inspired me to want to work in restoration in museums, but on a much different side of it than taking a brush to the artwork myself. I want to study the artwork and figure out how they were made and how they can be fixed. I also want to work to make places like the Villa Farnesina more accessible to the people who can’t get there physically. Everyone should be able to experience their favorite artwork, even if they can’t fly to Rome.

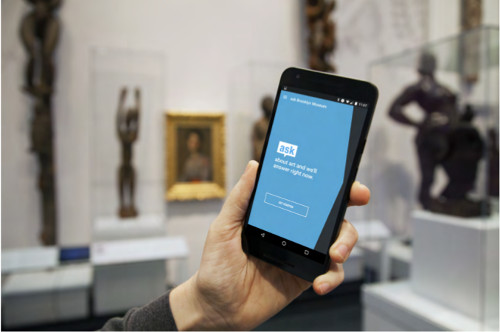

Thing: Brooklyn Museum’s Ask App

I am fortunate enough to be taking a class taught by Professor Devine, titled Museums and Digital Culture. Last week we had our class at the Brooklyn Museum, where Professor Devine is the Director of Visitor Experience and Engagement. We began the class with a presentation Professor Devine gives to investors and those interested about the app. It was created in three different phases. The first sent “Gallery Hosts” into certain exhibitions with vests telling visitors to ask them questions. The response was good, people would ask them questions about art, among other things. Phase two had “Gallery Hosts” in front of certain pieces of art, who would answer questions, but who would also hand out cards that showed visitors how to get to another piece of recommended art. This backfired, as most people wanted something more personalized than a preprinted card. Finally the last phase began, which is what inspired the Ask App. Ipods were given to members and select test groups upon entering the Museum with imessage that was sent to the Curator. With this phase the team was concerned the most with “screen suck” or that people would be too involved with their screens to actually look at art. They found that this wasn’t the case, especially when the curator could prompt visitors to look at specific pieces of the art he was describing.

From the third phase, the Ask App was born. Now, anyone who walks into the Brooklyn Museum can download it off of the App store, and speak to an art historian about art. During this class we were sent loose in the Museum to try it out, and I had a fantastic discussion with one of the team members about their Egyptian art exhibit. After this, we got to meet the team and see how the system worked.

While the only thing a visitor sees is a screen similar to imessage, the team sees a screen full of coded numbers asking them questions. One team member showed us how she would split her screen between the incoming conversations and the Brooklyn Museums Wiki, something she updated when no one was asking questions.

I had never been to the Brooklyn Museum before, but I couldn’t believe how fun it was to experience it with the Ask App. It’s a really cool tool to keep visitors interested that I believe all Museums should start to use. Not only does it get you to look at art closer, it also encourages you to see more of the Museum and stay engaged with it.