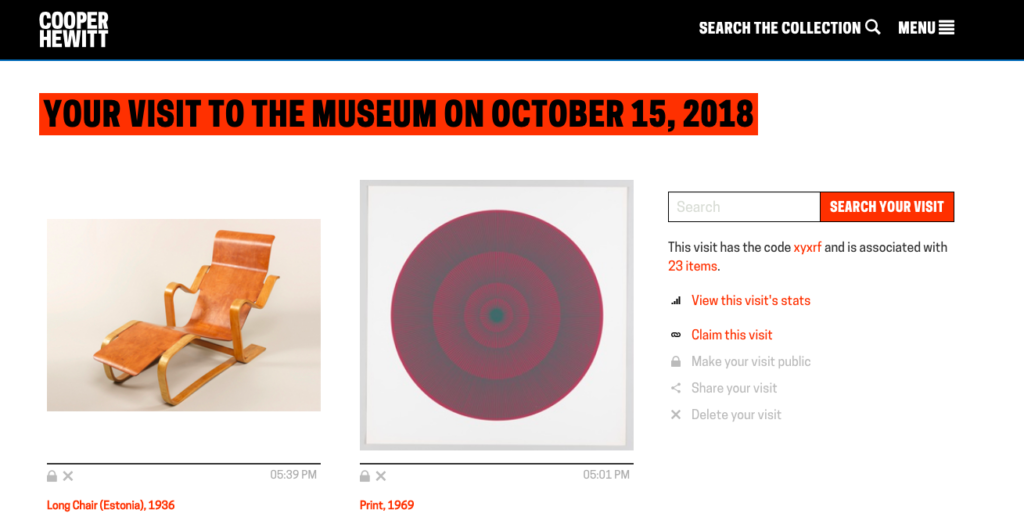

The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum is my all time favorite, not just because of the well-curated collections or exhibitions, but the great museum experience design impresses me as well. When I searched online for events, the Cooper Hewitt Museum popped up in my head and that’s how I found this salon event as part of the National Design Award Week 2018. The 2018 National Design Award aims to honor excellent and innovative American design, and also seeks to raise awareness of the impact of design in the education sector (“National Design Award”, 2018). National Design Awards 2018 included a bunch of activities, such as workshops led by Award-winning designers, exhibitions, panel talks, and salon events. Because of my landscape architecture design background and my interest in designing for human beings, I chose to attend the “Human Experience/Built Environment” salon.

BRIEF INTRO OF HUMAN EXPERIENCE/BUILT ENVIRONMENT SALON

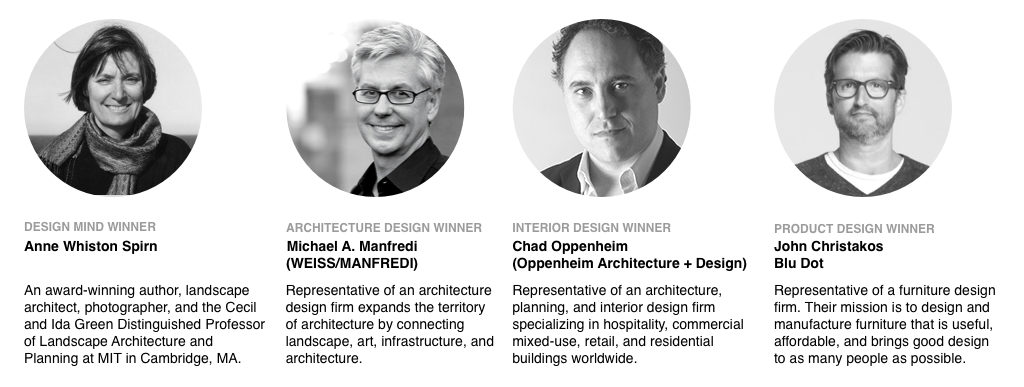

This event invited four National Design Award winners to share their creative /collaborative process for designing human experiences, challenges while designing, and the relationships between the built environment and designers (“2018 National Design Awards | Winners’ Salon & Master Classes”, 2018). Four award-winning teams/individuals are from different backgrounds. It’s a combination of a creative author, a furniture designer, an architect and an interior designer.

CREATIVE PROCESS

The salon started with inviting winners to share the creative process of their design works. Anne Whiston Spirn shared her process from an author perspective as the starting point. She is a person who would always start with an observation through her own eyes or the frame in the camera. She believes observation could reveal many things that you might ignore in your day-to-day life, for example, a buried river in the city or any other invisible forces that support human’s life. By doing so, observation can actually uncover the truth and yell us more about how life is lived. She will also talk to locals while observing in order to get the overall picture as a whole context. Michael Manfredi, the architect who represents WEISS/MANFREDI, added that his way of doing environmental design by talking to the local communities before even starts to sketch anything. When starting a new project, he would always keep “humanity” in mind, and reminds himself to be a person that knows nothing but eager to learn from and interact with communities. Chad Oppenheim from Oppenheim Architecture + Design tends to initiate the process from a childlike perspective. He goes to the site, wanders around and explores the environment like a boy back in the time when there was no Xbox and Gameboy. This approach helps him to discover the relationship between nature and humans, so he can really design for human experiences. Lastly, unlike other designers in this talk, as a furniture designer, John Christakos, the product designer of Blu Dot, oftentimes discusses with his partners about what piece of furniture they should design in the very beginning. Then they will sketch as a team to iterate the design work until the design goes to prototyping. That’s the reason why they never mark any of the design pieces as an individual work.

CHALLENGES AND COLLABORATION PROCESS

Manfredi mentioned how climate change impacts his consideration of spatial design as an architect. In the past, architects or urban planners didn’t really have to consider how to deal with the life-threatening storms, except in a waterfront neighborhood. But now, it has become a baseline requirement when designing spaces. He also shared how he collaborated with local dog owner communities in order to design a great dog park. His team facilitated a conversation of the local dog community, so each dog owner group could voice their opinion, and exchange their thoughts at the same time. After the conversation, the team sketched the park based on the discussion, then presented to the groups in order to receive valuable feedback. When the park was built and finally open to the public, the dog community was really satisfied with the outcome.

REFLECTION

1. Collaborating with communities is the key to designing good human experiences.

In my opinion, the spatial design discipline might be the pioneer of “user experience design.” For instance, when I studied landscape architecture design in college, to go on a field trip for observation already became a “must-have” process when designing a space. The purpose of going on a field trip is to understand the relationship between space/environment and the people. During the trip, designers are required to get to know about the local community as much as possible. Designers can either talk to local people directly, live with them for a few days, or just participate in local events. These methods will enable designers to discover the problems affecting an area, then explore the opportunity for solutions. Thus, it’s pretty common for architects/landscape architects to interact with communities and this “interaction” has even become part of the key process of spatial design.

Outside of the spatial design field, I feel designers tend not to have many interactions with communities (no matter if it’s a geographical community like a neighborhood, or a group of people that share something in common like small dog lovers). For example, when I worked as a UX designer, I did interact with “users” or “target audiences”, but the scale was smaller and it was more l goal-driven (wanted to know their devices usage patterns ), or task-driven (tested usability before releasing a new feature) approach.

So when Sasha Costanza-Chock wants designers to rethink the design processes in her article” Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice”, that recalled my memory as a landscape architecture design student instantly. In her article, she encourages designers to address the challenges of communities by applying collaborative, creative methods as part of the design process, and to be a “people first” designer (Costanza-Chock 2).

When one of the winners, Whiston Spirn, works on her projects in West Philadelphia, she collaborates with locals by treating locals as experts based on their lived experiences. Her team focuses on building a sustainable, community-led living environment by inviting locals to share their knowledge and teaching them about landscape literacy. In her design process, designers are more like facilitators than experts. The other winner Manfredi, invites people who will be impacted directly in the future to join the design discussion. He wants to create an environment in which designed is based on the prioritized impacts for the community. These methods actually match the framework mentioned by Costanza-Chock in the Design Justice article. No wonder the final design outcomes were engaging and resident friendly, and even won the prizes.

2.Lack of diversity in design industry

When I first saw the winners in front of the audience, I was a bit disappointed. Three of the four winners are male, and there were no people of color except white people, nor people with disabilities. I thought the topic is about designing human experiences in America, a place that is full of diverse cultures, languages, and people, which should lead the topic to accommodate various needs and situations that are more inclusive. This fact reminds me of Jennifer Vinopal’s article about diversity in library staffing (“The Quest for Diversity in Library Staffing” 2016). She brought up the issue about “lacking in diversity based on race and ethnicity, age, disability, educational background, gender identity, sexual orientation, and other demographic differences” (“The Quest for Diversity in Library Staffing” 2016). Vinopal’s finding could actually apply to almost all work fields, including design disciplines. Her intention to raise the awareness of lack of diversity in the workplace aims to combat “the oppression that is caused by privilege, bias, and the attendant power differentials at no matter individual or systematic levels” (“The Quest for Diversity in Library Staffing” 2016).

Incorporating every possible role to every work field seems a bit impossible for now, and I am not sure if this is a good approach to solve the problem. When we discussed difficult heritage a few weeks ago, I defended Maya Lin’s design of Vietnam Veterans Memorial by stating “designers don’t necessarily have to be part of the group they design for”, because she was being accused as an unqualified designer due to her role as an “outsider” (meaning that there is no Vietnam veterans in her family). In this case, because the objective is controversial, the interpretation of the memorial is always different for each individual, and it’s hard to find a Vietnam veteran who has the skillset, and also who is not suffering from Post-traumatic stress disorder to design this monument. Therefore I don’t think this approach works here. However, there should be a better way to address the lack of diversity issue in every work field. Costanza-Chock already initiated the solution by applying a doable design framework to improve not only the design process but also the final outcome of the design. Whiston Spirn does co-work with the communities for over decades and the result is amazingly impactful in a good way. There would definitely be more good solutions to accommodate this issue.

This event raises my awareness of two topics: design justice and work field diversity. Some of the practitioners in design disciplines already integrate similar methods into their work process to make the design more welcoming and accomondable in most situations. We should make this notion more wide spread through to different disciplines to make this change happen.

RELATED SOURCES:

- “2018 National Design Award – About The Awards.” Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 31 Oct. 2018, https://www.cooperhewitt.org/national-design-awards/

- “2018 National Design Award Winners.” Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 31 Oct. 2018, https://www.cooperhewitt.org/national-design-awards/2018-national-design-awards-winners/

- COSTANZA-CHOCK, Sasha.“Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice.” Design Research Society 2018 Catalyst, 25th-28th, June, 2018

- Vinopal, Jennifer.”The Quest for Diversity in Library Staffing.” In The Library With The Lead Pipe, 2016, http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2016/quest-for-diversity/

Take a Selfie with Mascot

Take a Selfie with Mascot

Decode Confidential

Decode Confidential