Category: Sula

Achieving Digital at the Met

I attended an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized by Professor Villaespesa for Info School students. While there, we heard from Loic Tallon, the museum’s Chief Digital Officer, and Jennie Choi, the General Manager of Collection Information. We heard about their work at the museum and their approaches to the idea of digital at an institution as large and as entrenched in its ways as the Met can be.

I attended an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized by Professor Villaespesa for Info School students. While there, we heard from Loic Tallon, the museum’s Chief Digital Officer, and Jennie Choi, the General Manager of Collection Information. We heard about their work at the museum and their approaches to the idea of digital at an institution as large and as entrenched in its ways as the Met can be.

One of Tallon’s central theses to his work at the Met is that “the strategy of centralizing responsibility for digital transformation within a single, distinct department is reaching its limits. Now a broader institutional approach is needed.” It’s a theme he’s written on for the Met’s blog and a topic he discussed during his talk. The boundaries for digital initiatives in museums are wavy, indistinct lines. In his blog post, he charts out different responsibilities that fall under the scope of “digital” at various museums around the country. No two museums approach it the same way, and it comes increasingly reductive to limit certain processes to a digital department, when the reality is that all departments should be examining their workflows for places they can adapt and embrace new technologies.

At the Met, the Digital department is comprised of three teams: a team dedicated to collections information and data management, a team of content producers, and a team for product development. Tallon described their work as divided between the two paths people can take to interact with the museum. The first path is the in person experience. When a visitor enters the Met’s physical spaces, what work can the digital team do to enhance their experience? The second path is for the remote user, who interacts with the Met’s collection and its services online. What does the digital team need to accomplish to present the museum to the rest of the world?

The first path is generally constrained by space and exhibit demands, but the possibilities for the second path are wide open. The questions regarding digital at the Met are similar to the ones the High asked itself for its physical gallery reinstallation. How does a museum stay relevant, provide the best representation of its collection, and engage with as many people as possible?

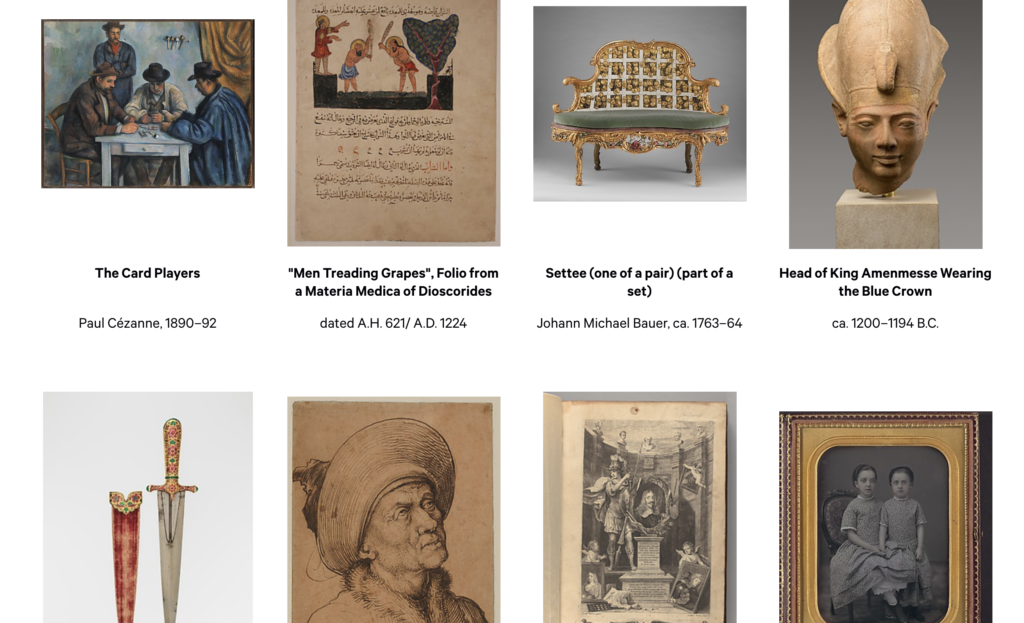

At the Met, the answer was to invest more heavily in digital. Tallon admitted that the museum’s online presence had very little effect on the museum’s bottom line. And yet, it’s a presence worth building on as the world increasingly engages with itself online. Last year, the Met launched it’s Open Access intiative. They made high quality images of their public domain collection available to anyone under a Creative Commons Zero license and worked with Wikimedia and Google to make their images more accessible on the web. Just last month in October, they made those images along with information about all the works in the museum’s collection available via API.

Since the launch of the Open Access initiative, the Met has been able to reach a larger audience with images from their collection. While it hasn’t resulted in a significant increase in traffic to the Met’s website, its images are available on Wikipedia pages and Google search results. These other platforms allow a wider audience to engage with the Met’s collection, including users who speak a language other than English–something the Met itself would never have been able to do on its own. The API is only a month old, so results remain to be seen. Those interested in updates should keep an eye on Tallon’s posts on the Met’s blog.

In the second half, we heard from Jennie Choi, General Manager of Collection Information. With over 20 years of experience at the Met, she had some really interesting insights into the museum’s metadata. The primary piece of software used at the Met is The Museum System, a full collections management system that feeds its information into other parts of the Met, including NetX, the museum’s digital asset management system, and the museum’s information kiosks.

The Met has a long history of making and keeping records on its collection, but it’s only in the last few years that it has created a set of cataloguing standards and worked across departments to standardize data like artist names and object provenance. Previously, each curatorial department was responsible for its own records, which created heavy inconsistencies in how works were labeled and could be found online. Choi was on a team that worked with curators over two years to bring all that metadata under one roof and continues to work with departments to bulk out information available on works from the collection.

Choi’s latest project is tagging works from the collection with content keywords–something that’s never previously been done. In an initial pass through the collection, the museum outsourced the work to a team of 70 who worked 24/7 for three months to assign various tags to works. They looked for things like objects featured in paintings, or whether the work depicted a man or woman. There have already been major challenges to this. Using such a large group of taggers created inconsistencies, and the lack of a standard created inaccuracies. There were also cultural differences that hindered the quality of the documentation. For example, it was hard for the team to accurately identify satire in the drawings collection. Given the opportunity to do it again, Choi says she would’ve preferred to work with a smaller team with more training over a longer period of time. Due to the nature of the project funding, the initial work had to be completed within three months and the tags need to be reviewed before they can be added to public-facing systems.

I thought this was a fascinating look behind the digital initiatives at the Met. It felt perfectly in line with my observation of the High. Both institutions are in the midst of interrogating their stewardship of their respective collections. In the High’s case, it was of their actual physical space. For the Met, a full scale physical reorganization is improbable, but they have untapped potential in carving out a digital space of their own.

Observation of The Rubin Museum of Art

Objective

Brief intro of The Rubin Museum of Art

Brief intro of “The Shrine Room”

General

The Shrine Room:

Reflection

Related Resources

- “About the Museum” The Rubin Museum of Art, 30 Nov. 2018, http://rubinmuseum.org/about

- “The Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room” The Rubin Museum of Art, 30 Nov. 2018, http://rubinmuseum.org/events/exhibitions/the-tibetan-buddhist-shrine-room

- Michele Valerie Cloonan.“W(H)ITHER PRESERVATION?” The Library Quarterly, Vol 71(2), 231-242, 2001

Event- Inclusive Design 24

The event I attended is an online event on web accessibility called the Inclusive Design 24 conference. It was the 5th annual ID24, which is a 24-hour live stream international event where different topics were discussed from October 10th to October 11th. I did not watch the full 24 hours, but I was able to catch some of the talks and have gone back to watch more of it since, as they were streamed and saved on YouTube. This seemed like an important event to partake in, as it is relevant to a few of my projects this semester (including my final paper for this class) as well as is a good event for everyone in the information profession to view as it provides new ideas and thoughts on the state of web accessibility. It is also a unique event because the 24 hours of streaming allows it to include numerous international voices which can often not be included in events or conferences that require physical attendance, especially for the disability community. This allows every type of person to participate in the event through presenting or watching the hours of content, without being required to travel. Additionally, because this is the 5th year of this event, it operates relatively fluidly, and the people involved seem excited by the conversation and size of the event. Everyone presenting was very happy to be representing an organization or be an expert in the field to share their insights and ideas on the issues.

What they are trying to do is not limit creativity of web design but encourage people to take into consideration a whole bunch of different disabilities, so the internet feels like a place of inclusion and equality, and helps people participating in the medium instead of discouraging them. This event also coincided nicely with our readings also discussed on October 10th on user centered design/ design justice, showing how an inclusive thought process can be implemented in the real-world practice of creation. Making everything high contrast (though high contrast is not the same for everyone) and sites easy to click is beneficial for not only low vision users, but to those users on the website outside in the sunlight. Taking into account who has access, and the value of making things accessible in a sensory way but also where connection is limited. The group is trying to connect all people, whatever circumstance, every way they can for the future.

While the event itself seemed low budget with some questionable connection and presentations at times, and I am not sure most people would actually commit to watching 24 hours of this all at once, but it was a very global event, and is an attempt to connect and take into consideration numerous types of technology consumers. There were different college groups who watched at various times, and a decent amount of twitter engagement. The hashtag #ID24, was used throughout the event, and the tweets were positive, and there is the ability to communicate with what the speakers were talking about.

The most important lesson I think I took from the event is that you are not creating an experience (even though the word user experience implies exactly that) your creating an environment for people to experience. Whether it is entirely usable at face value to the user, or if they can easily adapt and add to it (i.e. screen readers, different methods of selecting content, inverted colors or customized high contrast settings) to make it personalized and accessible, the structure of what your creating is the environment. In terms of accessibility, they also emphasized that the basics are what gets overlooked a lot of times in web design and that is what leaves people behind. Web designers often skip over the basic structure of a website, like the html, which is really where most of the accessible adaptations take place, because the websites personal style does not matter as much as the content if some sort of adapter is going to alter the style anyway.

The underlying theme is that people care about accessibility, but it is a big undertaking for people that do not know how to go about implementing components into their design. People know they are excluding people, but it is hard to start the process of designing better. They discussed a lot of different topics, from high contrast mode, accessible online payments, WordPress, the list goes on and on within the 24 hours of content.

When thinking about the readings this semester, it goes back to design justice. They are very good at pointing out what does not work and why a lot of the websites out there are poorly designed for accessibility. Additionally, there is not one right solution for everyone, but there are things that can make it better for everyone. The more control the user in some of the design choices, like contrast and color, that might be a better solution then designing one website to fit everyone’s needs from the moment they type in the URL.

This event gives a lot of voices of the disabled design community a larger platform of which to speak. As Costanza-Chock writes,

The key lessons include: involving members of the community that is most directly affected by the issue that you are focusing on is crucial, both because it’s ethical, and also because the tacit and experiential knowledge of community members is sure to produce ideas, approaches and innovations that a non-member of the community would be very unlikely to come up with. It is also possible to create formal community accountability mechanisms in design processes (Costanza-Chock 9).

There is a lot still to be done in creating a web that is designed with all people in mind, hence this event has been occurring for the past 5 years, and likely as computer technology changes there will always be more things to discuss when it comes to designing content for inclusivity. It seems likely this event will continue for years to come bringing about new thoughts, ideas and innovations in web accessibility.

Bibliography

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice. pp 1-14.

Visiting a Closed Museum: The High Museum’s Reinstallation

2018 Reinstallation: Refreshed. Reimagined. Revealed. from High Museum of Art Atlanta on Vimeo.

When I visited the High Museum in Atlanta in the beginning of October, I caught it during an awkward in-between time. The museum was in the final stage of mounting a total gallery reinstallation and almost the entire space was closed. There was a single exhibit on display in an outbuilding, With Drawn Arms: Glenn Kaino and Tommie Smith, but the museum was otherwise closed. This might seem like an odd choice for an observation site. I’d never been to the High before, and I wouldn’t be able to visit it again once the galleries had reopened to the public.

I wouldn’t be able to make a before and after comparison, but I wanted to visit the High because the reasons and circumstances surrounding a complete gallery reinstallation tap into questions surrounding collections and archives and how the maintenance of them and the spaces that house them all end users to interface with them. In the case of museums like the High, that means its visitors, both from around the world and from the local Atlanta community.

As part of an FAQ (which has been archived since the museum’s unveiling) on the High’s website, the museum stated:

“Reinstallation is a planned part of the Museum’s long-term strategy. It’s an opportunity for us to rethink the way we present the artwork in our collection. Since 2005, we’ve added nearly 7,000 new objects to the permanent collection. Now feels like the right time to showcase these works, address wayfinding, spruce up the galleries, and make the collection presentations more cohesive and engaging for visitors.”

These ideas called to mind the the themes Joan Schwartz and Terry Cook addressed in “Archive, Record, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory”. The archive, or collection, and its keepers must be responsive and adaptive to context and change. Keepers should also acknowledge their responsibility in creating an archive that is representative and the archive’s role in the “exercise of power—power over information and power of information institutions. Also interwoven throughout is the crisis of representation—the power of records and archives as representations and the representation of power in records and archives” (Schwartz and Cook 9).

As of the 2010 census, Atlanta’s population was 54 percent black. The city is also the birthplace of Martin Luther King Jr. and the home of the Center for Civil and Human Rights. During my visit I was able to speak with Margaret Wilkerson, a Museum Educator and Docent Manager, who stated that part of the plan was to create more space for the High’s collection of civil rights era photography and to bring together the museum’s collections of African art, which had been previously scattered in different galleries. A review of the reinstallation in ArtsATL by Catherine Fox noted “[t]he High has made a concerted and noticeable effort to” include more art from women and people of color. A preview of the reinstallation in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution noticed that in the new layout “African art might share space with self-taught artists from the American South, and self-taught artists will be placed up against contemporary artists to show the energy exchanged between the two”–another aspect of the reinstallation that Wilkerson mentioned in our conversation.

This integration of different pieces from the collection works to create “stories linking works throughout the museum” (Fox). Wilkerson admitted that a weakness of the High in the past was it’s tendency to move from blockbuster exhibition to blockbuster exhibition, rather than focusing and drawing on the strength of its own collection. Creating narratives from work pulled from across time and location would hopefully draw in visitors who would be interested in returning to the High even when something major like it’s current Yayoi Kusama exhibition isn’t in town.

Ironically, the only work I was able to see was a temporary exhibit. But the themes of With Drawn Arms demonstrate the High’s desire to bring the past into the present and “[showcase] artworks relevant to communities from Atlanta and beyond.” A collaboration between Olympic gold medalist Tommie Smith and artist Glenn Kaino, With Drawn Arms brings together art and artifacts representing Smith’s act of protest during the the 1968 Olympic games. While the Star Spangled Banner played during his medal ceremony, Smith and teammate John Carlos bowed their heads and held up black gloved fists to represent Black Power and protest the mistreatment and denial of rights faced by black Americans. Colin Kaepernick’s Nike campaign had debuted just weeks before the exhibition opened and direct connections could be drawn between every element of Smith’s protest and Kaepernick’s.

The most striking work was a series of bronze casts Kaino created of Smith’s arm. The casts were hung from the ceiling and filled the room. Titled “Bridge,” Kaino describes the work on his website as “a golden path leading forward from the present but connected to the past, a spectacular reconciliation of a historic record, an individual memory, and a public symbol all renegotiated in an infrastructure of time to creates stories of the now.”

In visiting the High, I wasn’t able to actually observe much, but a museum (or archive) is not only it’s collection. It’s also the context and conversation around the collection. The reinstallation itself is designed to allow the museum to make adjustments and respond to its users. Whether their efforts create a successful bridge remains to be seen. I personally won’t be able to go see it for awhile. But I think the very fact that the museum recognized its need to pause and re-examine its role and the significance of its works is a good sign.

Observation: Brooklyn Museum

For my observation, I spent time watching and exploring the Brooklyn Museum. I have had to do many museum observations this semester as part of the Museums and Digital Culture program. It made the most sense for me to observe a museum, and specifically this one for longer, for the purpose of this assignment, because I have seen the evolution of this institution over many years. I observed the exhibits on Sunday mid-morning October 7th, which was potentially not the best day to go, because the museum itself was relatively empty at that time.

Growing up, I frequently attended the Brooklyn Museum, and the permanent collections remained relatively stagnant throughout the early 2000s. For years, they seemingly did not evolve or make much attempt at relevancy, in my opinion, including topical themes and creating much personal interest. I do not remember seeing many of their temporary exhibits, but their permanent collection did not use the space to its fullest. Following the redesign of the front of the museum, much of the culture has changed, and there were several people near the front of the building, as a hangout location and not so much to view the cultural institution. Recently the interior content of the museum has become increasingly socially conscious and they are clearly working on finding their voice in the greater New York art scene, while changing their curation of their permanent collection so the context of the pieces has been evolving with the space. The museum itself is experimenting with what kind of audience is wants to attract and what kind art it wants to display to be relevant, different and attractive to the wider audience, and brining people in past the outdoor seats.

The pieces I remember seeing growing up are mostly still on display, but they have become almost a scavenger hunt because their locations have moved around, and they are being curated differently with new works surrounding them to change the conversation. As Cloonan writes, “Artifacts may shed light on the past, yet when these cultural remnants are placed into contemporary context something new is created,” (Cloonan 231). They have given new context to their work surrounding new themes, in this current climate to bring out new meaning to the work. As a temporary exhibit, they have “Float” is an interesting molten glass works mixed amongst the permanent collection on the American Art floor, offers a level of intrigue and surround much older work sometimes with words that correlate with the older art.

In terms of difficult heritage, they have chosen to highlight a lot of political art topics to display, and more importantly create a conversation about. Two of their temporary collections that really stand out as making a statement on difficult heritage are the “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” and “Half of the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection.” They are using art to display difficult moments in American history, which are still relevant in today’s political climate, and spark conversation. It should be noted however that these exhibits were not incredibly loud in terms of discussion, possibly because while most people were there alone or in groups of two, there was not enough people in the space to facilitate conversation amongst friends. For the most part people seemed very reflective. One example of this is The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago, which over the past 10 years or so now has created a whole feminist wing surrounding this piece, and an increasing focus on feminist art across the museum, when it used to be just this piece was the focal point of feminism in the Brooklyn Museum. The room housing The Dinner Party, there was only a group of two in there at the same time as myself, and it was very quiet, no one seemed to want to make any noise when viewing the pieces, likely because the walls are dark, and there is so much to see, that the conversation seemed to mostly occur outside of the space. The two temporary exhibits, the feminist wing, the American art floor and the restaurant were the most crowded for the Sunday morning. Granted, no room I went into could be considered crowded (there was plenty of walking and viewing space surrounding the wall text and images), but the other floors had hardly any foot traffic. I also did not stumble upon any walking tour groups, and I did not see many docents and museum staff, especially once in the gallery space after the front lobby where you get tickets and such. However, compared to the other floors and rooms which have very few people, the temporary and more relevant artworks were the most visited.

It is of note as well that I was there the morning after their big first Saturday event (almost always a well-attended monthly event for the museum) and a week too early for their Syrian Refugee exhibit, which obviously is very topical, in comparing Syrian refugees from the past to the present through art, and is definitely a reason to go back to the museum when I have more time, but also possibly a reason there were not as many people on the day that I went because they were timing their visits for events and certain exhibits.

Their archiving system is very open, you can observe much of the process just by being in the exhibits. In the Egyptian Art section for example, while I did not see any archivists or curators actively working at least within the public exhibit (again likely due to the time and day I was observing and exploring) but in one room there was a relatively large area sectioned off, which was not entirely hidden, where they were clearly redoing a portion of the exhibit, and presumably getting ready to add the pieces some of which were on the tables to the display in the coming days. Their actual archives are also currently mostly closed to the public, but they have visual storage behind glass doors you can see through. There weren’t as many docent staff at work when I went there, it seemed mostly security guard and people in charge of the front of house activity, yet with the very open collection side of the museum, it is apparent that a lot of work is being done, just not as much on the volunteer/educational side of the museum, especially during one of their presumably slower hours.

Bibliography

Cloonan, Michèle Valerie. “W(H)ITHER Preservation?” The Library Quarterly, vol. 71, no. 2, 2001, pp. 231-242.

Macdonald, Sharon. “Is ‘Difficult Heritage’ Still ‘Difficult’?: Why Public Acknowledgement of Past Perpetration May No Longer Be So Unsettling to Collective Identities.” Museum International, pp. 265-268.

Protected: Observation: Columbia Center for Oral History

#NoHateALA: What’s next for our community? – Event Review

On October 16th, the group Racial and Social Justice in the Library hosted a meeting titled “#NoHateALA: What’s next for our community?” for librarians and information professionals. Two organizers, one librarian from the New York Institute of Technology and one librarian from the NYPL Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, spoke to a small group of three information professionals from various libraries. I agreed to keep the names of the organizers and attendees anonymous.

The meeting, held at the Metropolitan New York Library Council’s Midtown office, was organized to discuss the the American Library Association’s recent decision to put forth an amendment to the Library Bill of Rights that sanctioned hate groups meeting in public libraries. This decision sparked outrage among those in the library and information profession as well as among community members. Due to this outrage, the amendment was rescinded and a new version will be released. Nevertheless, ALA’s decision to allow hate groups to meet in public libraries has created a crisis in the profession. This meeting was organized to discuss what this amendment means for the profession and how we should respond as a community.

The meeting began with an introduction to the amendment and a recap of the events surrounding the passing of the amendment. The amendment was initially brought up when a librarian approached the ALA Intellectual Freedom Committee about the KKK being given meeting space in their library. The IFC discussed the issue and ultimately decided that, based on the First Amendment right to free speech, the ALA should officially allow hate groups to have a presence in libraries. The amendment passed, only to be rescinded in August after information professionals on Twitter expressed their anger at the amendment with the hashtag #NoHateALA.

The two organizers posed several questions pre-written on posters to generate discussion among meeting participants. As we discussed each question, post-it notes were added to the posters. The questions were:

- What or who is ALA for? Is it for librarians?

- Is ALA working for us? How can ALA work better for us?

- Are there other professional organizations doing this better? How so?

- Can neutrality [in libraries] be an instrument for violence? For prejudice?

In response to the first question, one organizer immediately replied with a definitive “No, it’s not for librarians.” As an African American woman and a librarian, she explained that as soon as hate groups were allowed into the library, they were terrorizing her existence. Overall, the group agreed that hate groups probably shouldn’t be allowed in library spaces if ALA and libraries want to continue to promote “diversity” among their staff and patrons and keep the staff and patrons safe.

ALA was described during the meeting as a “guiding force” of the profession, and it was acknowledged that acting counter to the wishes or rules of ALA could be basis for losing a job, particularly for librarians that are already vulnerable (whom are often the same librarians that are affected by the presence of hate groups in libraries!). The professional risk involved in defying ALA can be more than symbolic.

There was a lot of discussion about the legality of the actions of hate groups and the ALA, but I and others argued that purely legal pathways to social change are quite often not the most effective, nor do they necessarily reflect the moral or ethical choice. There is a great social context of racism, hate, and discrimination that ALA is willfully ignoring by projecting neutrality.

A large part of the meeting was spent discussing the fourth question about neutrality. While the ALA believes itself to be neutral because it sanctions the presence of hate groups in library spaces just as it does other religious and political groups, in reality, neutrality is an impossibility. As Robert Jenson explains in “The Myth of the Neutral Professional,”

…a society is moving in a certain direction—power is distributed in a certain manner, leading to certain kinds of institutions and relationships, which distribute the resources of the society in certain ways. We cannot pretend that by sitting still—by claiming to be neutral—we can avoid accountability for our roles (which will vary according to one’s place in the system). A claim to neutrality means simply that one is not taking a position on that distribution of power and its consequences, which is a passive acceptance of the existing distribution. Even this is a political choice and thus inherently non-neutral. (2006: 4)

In other words, as one participant said, when the ALA projects neutrality, it is shying away from responsibility to make a moral choice that may not be wildly popular among free speech advocates, but would protect library staff and patrons that often see the library as a safer space. The first step, according to the meeting organizers, is recognizing that some expression is oppressive to others, and that neutrality is a myth. A second step is for ALA to more precisely define “hate groups” so that a more precise and productive conversation can be had about this issue.

The meeting was concluded with the question: “What can we do immediately?”. It was suggested that less vulnerable librarians (white men and women in particular) could support their colleagues in more vulnerable positions in standing up against hate groups in the libraries, though ultimately it would be in the hands of administrators with the power to hire and fire employees to stand up against such policies. There will be a Part 2 of this meeting following the release of the new ALA amendment to discuss more concrete action steps.

References

Jensen, R. (2006). The Myth of the Neutral Professional. Electronic Magazine of Multicultural Education, 8(2), 1-9. Retrieved October 15, 2018 from https://www.eastern.edu/publications/emme/2006fall/jensen.pdf.

Protected: Observation and Interview – Designity

The Uncomfortable Archive

Every year, The Archivist Round Table (A.R.T.) produces New York Archives Week. A week full of commemorative activities aimed to inform the general public of the diverse array of archival materials in the NYC metropolitan area. A.R.T. hosts three signature events: the A.R.T. awards ceremony, the K-12 Archives Education Institute, and an all day symposium. On October 19, I attended the annual symposium held at the Center for Jewish History.

This year, fellow Pratt LIS students and I spent the day uncovering truths about working with the “uncomfortable archive.” The symposium consisted of a keynote speaker and four panels. All of the speakers and panels focused on various aspects of archiving sensitive material, bringing to light the broader questions of what it means to preserve and acknowledge the existence of controversial episodes throughout history.

The first panel centered around curatorial choices for a exhibition surrounding the holocaust and mental health. The first speaker was Marissa Hollywood, Associate Director at Kupferberg Holocaust Center (KHC) at Queensboro Community College (QCC). From their website, “the Kupferberg Holocaust Center uses the lessons of the Holocaust and other mass atrocities to teach and empower citizens to become agents of positive and social change in their lives and in their community.”1 Mrs. Hollywood spoke about how the space serves as an exhibition center and a library and touched upon the importance of its accessibility to not only the students but also the community.

In 2015 the KHC hosted an exhibition centered upon the discovery of a jacket from the Dachau concentration camp. The jacket belonged to Benzion Peresecki (Ben Peres), a Lithuanian Jew, was a prisoner at Dachau for 10 months. He kept the jacket for 33 years. The exhibition told the story of his immigration to the US, his legal pursuit of reparations, and touched upon his mental health journey. Over 1500 documents, donated by Mr. Peresecki’s daughter, served as the supplemental material for the exhibition.

As Mrs. Hollywood described the overall staging of the exhibition and the design of the center, a quote in the “difficult heritage” reading by Sharon Macdonald popped into my head: “Should a representation remain coolly factual or use more emotive forms of staging?”2 In the end, I thought Mrs. Hollywood and the other speakers on this panel delivered an exhibit that traversed the line between factual and emotive very well. With this exhibition, they attempted to answer was how best to display this difficult heritage and to address the issue of trauma and mental health that proved critical in Mr. Peres struggle following WWII.

Olivia Tursi, a social worker, worked on the exhibition analyzing the mental health documents for the exhibition. Her presentation focused on Ben Peres’ mental health. She discussed the importance of the jacket as a source of a traumatic event but also symbolic of his survival. She also addressed how the jacket provided a sense of control of his narrative post WWII.

The third presenter was Dr. Cary Lane, Assistant Professor of English at QCC. Dr. Lane spoke about using student-centered approaches to engage students in difficult content. His presentation focused on the presentation of the documents and the engagement of the students with the exhibit. What I found interesting about Dr. Lane’s presentation is the focus of the diversity of the student population. As he spoke, I was reminded of a passage from the reading on archives by Joan Schwartz and Terry Cook:

“Remembering (or re-creating) the past through historical research in archival records is not simply ‘the retrieval of stored information, but the putting together of a claim about past states of affairs by means of a framework of shared cultural understanding.’”3

Dr. Lane spoke about how student involvement with the research of the jacket and the holocaust allowed them to not only understand the event, but relate its repercussions and emotions to their own lives. QCC is a very diverse campus and while the lives of these students may not have been personally affected by the holocaust, they could identify and share the emotions associated with such a traumatic event. I found this correlation and “shared trauma” was an interesting aspect to this exhibit.

Overall I found the entire event to be really fascinating. As library and information professionals, I believe that we hold a certain obligation to the community to exhibit the realities of historical situations that may otherwise be overlooked. Throughout the panels there were so many examples of archival exhibits that pushed the boundaries surrounding material that is “uncomfortable” to most audiences. As I was listening to the panelists, I was reminded about our readings regarding the power of the archive. Throughout the year we read examples of the power that archives wield. In all the examples of “uncomfortable archives,” I feel the presenters did a good job of highlighting the gravity of their subject matter with respect for those marginalized communities.

Sources:

- Hollywood, Marissa. “About the Center.” Kaufberg Holocaust Center. http://khc.qcc.cuny.edu (accessed October 22, 2018).

- Macdonald, Sharon. “Is ‘Difficult Heritage’ Still Difficult?” Museum International 265-268 (2016): 6-22.

- Schwartz, Joan M. and Terry Cook. “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory.” Archival Sceince 2 (2002): 1-19.