I visited the Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum to observe their “digital pen” project. Like all visitors, I was offered the pen to use for the duration of my visit in the same way many museums offer audio guides. The museum staff explained that touching the pen to a symbol on an object’s wall will save the object to a digital collection I could later retrieve on the museum’s website. The staff then handed me a ticket stub with a printed code. I would need the code to access my collection

For three hours I walked through every gallery of the museum, observing how visitors were making use of their pens. I watched as visitors gathered around dining-room sized tables scattered throughout the galleries. They were using the pens to create designs on the tables’ interactive screens.

I noticed a visitor struggling to use her pen on a wall label. A guard attempted to demonstrate its proper use. He struggled with the pen himself a bit and commented “These things can have a mind of their own. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t.” With assistance from the guard, the woman was finally able to save her object. The pen gave a satisfying vibration and flashed green lights to indicate successful contact. The woman then raised the pen to her ear. The guard told her “No, it’s in cyberspace. You can share your collection with a friend. Don’t lose your ticket.” I watched the woman wander into another gallery with her pen dangling from the cord on her wrist. She started taking photos with her phone. I asked the guard if people often asked for help with the pens. He replied “One hundred times a day!”

Another visitor tried to save every item along one wall. I watched as one after another, she went to each item’s label and tried out a jab-and-slide technique with a confused expression. I imagined her telling herself “it’s all in the wrist.” It was like watching a tourist re-swiping their subway card. I figured once you get it, it’s in your muscle memory.

Some visitors seemed to have mastered the object-saving usage of the pen. I observed two men saving items with ease. One of them, however, touched his pen on a waist high screen where a video was playing. A guard then intervened, letting him know that that particular screen was just a regular video and was not for meant for the pens. I could see how a visitor would make the mistake with so many interactive digital screens around.

Throughout my visit, I estimate that around half of visitors were at least trying out the pens. The other half of visitors were using their phones to capture objects and wall text. I watched one gallery for fifteen minutes. During that time, many people were twirling their pens by their cord but taking photos with their phones.

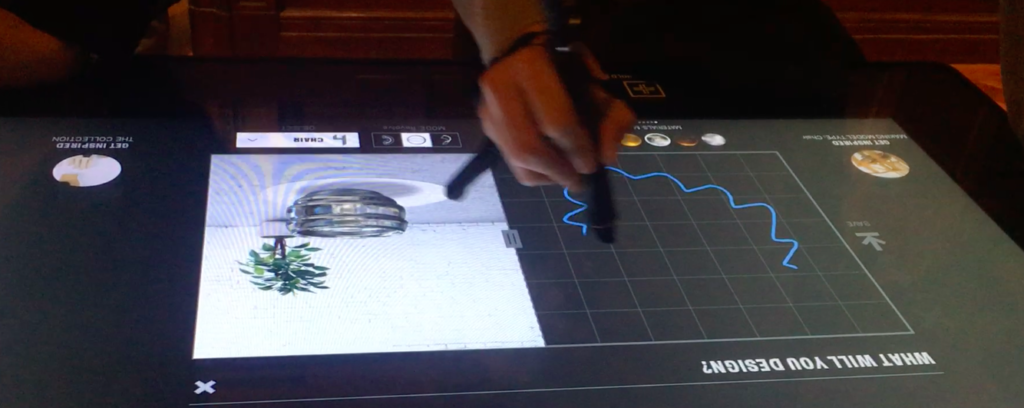

I turned my attention to the numerous digital tables throughout the galleries and watched as visitors experimented with the pens. A constant stream of images runs along the length of the rectangular screens. I watched on as a museum staff member giving a tour called the random floating images the “river of objects.” She explained that the museum has 200,000 objects in their collection but they focused on 4,000 for the river. From my estimation, there seemed to be around 100 or so images, based on the rate at which the same objects would loop through in the stream. The staff member demonstrated how you could swipe an object out of the river with a pen or finger and examine it more closely. You could then read interpretive text about the object or use the object as an inspiration for a digital design of your own.

Some visitors were using their pens to make gestural strokes on the screen. Images of objects from the museum’s collection would appear on the screen highlighting how the visitors line is echoed in a an object’s contour or design element. In my observations of the digital tables, I noticed that visitors spent the least amount of time on the gesture line exercise. The novelty of it seemed to dissipate quickly.

From my observation of visitors at the interactive tables, sessions lasted from a few seconds to about ten minutes. Visitors who created their own designs did not seem to be deliberate in their engagement. It was as if they were idly exploring the tool in free-form experimentation.

I observed several visitors loading their saved collection onto the touch screen and exploring their objects in more detail. There were multiple views, curatorial text and a scrolling bar of similar objects based on categories as varied as color, movement, and subject matter. There was no way to search for typical tombstone data like artist name, movement, object name, etc. From what I could tell, the tables did not include any typing functionality at all. The experience was gesture-oriented.

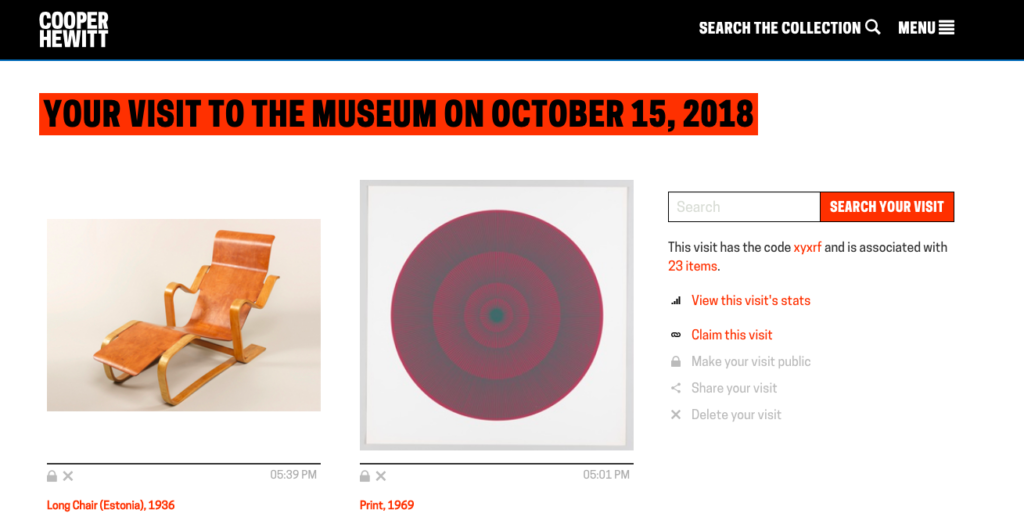

During my visit, I used the pen to assemble my own collection of objects. The museum website has a link to “retrieve your visit.” I could view most of the images I collected, although some objects that were registered by the pen were missing.

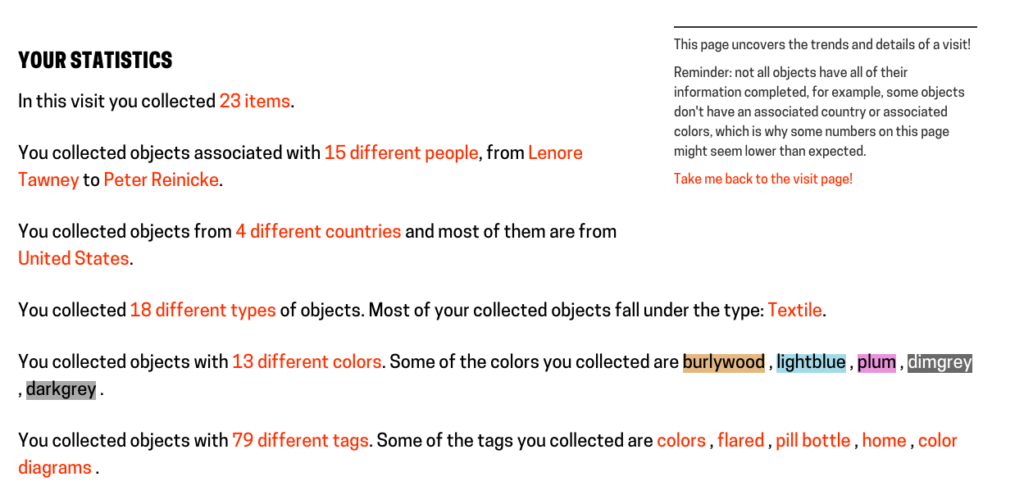

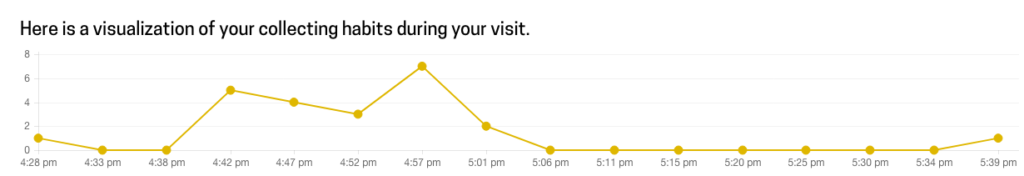

The website portal also allowed me to view stats on my “collecting habits” during my visit. To me, this information resembled the intrusiveness of big data. I thought of the tracking of my internet habits that are used to sell me products. I could find no particular value in the data they were tracking on me. The stats, if anything, seemed more useful for the museum’s own data on how visitors move through exhibitions.

The digital pen is certainly forward-thinking in the way that it recontextualizes a museum collection and redefines the gallery space as a creative zone for the visitor. In theory, it is in keeping with the predictions of Joe Touch, the director at the University of Southern California’s Information Sciences Institute:

The Internet will shift from the place we find cat videos to a background capability that will be a seamless part of how we live our everyday lives. We won’t think about ‘going online’ or ‘looking on the Internet’ for something — we’ll just be online, and just look. (Digital Life in 2025)

However, the pen is clunky, even when it works properly. The idea seems to be to incorporate the traditional experience of looking at objects in a museum into our current compulsion for information accrual in the digital realm. But the process introduces too many new physical objects that the visitor must learn how to navigate, and in the proper sequence–carry around an additional device besides your phone, walk away from the artwork to interact with numerous touch screens, and don’t lose your ticket code or your visit will seem inconsequential. The process is far from seamless.

The digital pen is more in line with the predictions made by technologists who foresee the increased role of big data. As Judith Donath, a fellow at Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, puts it, “We’ll have a picture of how someone has spent their time, the depth of their commitment to their hobbies, causes, friends, and family. This will change how we think about people, how we establish trust, how we negotiate change, failure, and success.” (Digital Life in 2025)

There is something futuristic about the digital pen/touch screen experiment. It is the most technologically sophisticated tool for museum visitor experience I have seen. However, its effect is less in line with technologists’ predictions of digital life seamlessly integrated with our physical experience and more in line with technologists’ predictions of big data dictating our actions and behaviors.

Designing the Pen. Retrieved from https://www.cooperhewitt.org/new-experience/designing-pen/

“Digital Life in 2025.” (2014). Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://assets.pewresearch.org/ wpcontent/uploads/sites/14/2014/03/PIP_Report_Future_of_the_Internet_Predictions_031114.pdf

Take a Selfie with Mascot

Take a Selfie with Mascot

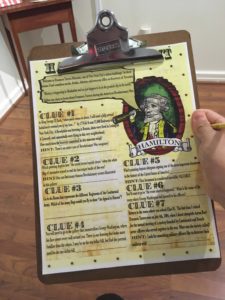

Decode Confidential

Decode Confidential

While walking around the exhibition I noticed the following image at each stop posted on the floor. A graphic of a camera encouraging the patron to stand in that precise spot to take a photo, suggestively for Instagram, Twitter, or some other form of social media as the graphic was followed by “#museumofillusions”. This idea of

While walking around the exhibition I noticed the following image at each stop posted on the floor. A graphic of a camera encouraging the patron to stand in that precise spot to take a photo, suggestively for Instagram, Twitter, or some other form of social media as the graphic was followed by “#museumofillusions”. This idea of

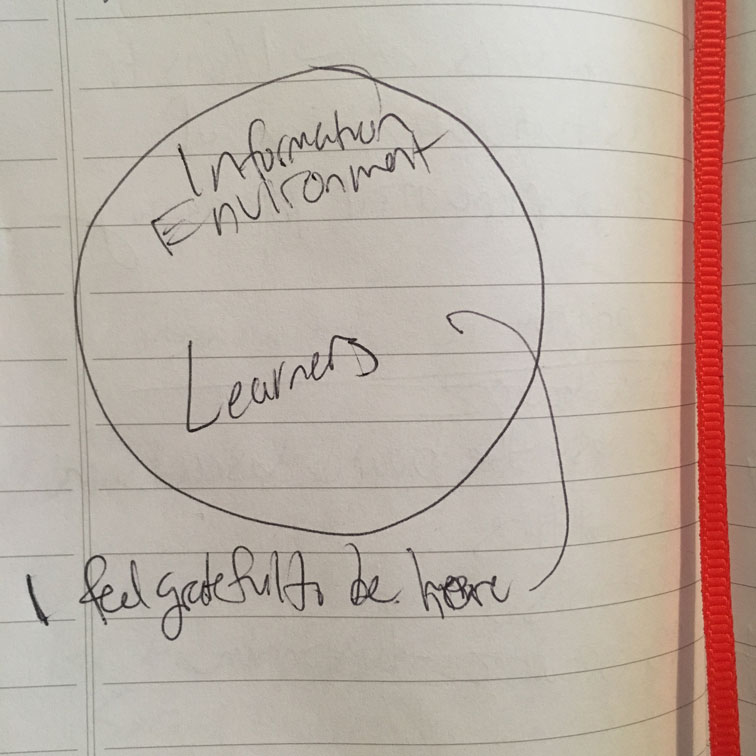

As I mentioned I wish I would have attended the exhibition with a friend. As most of the pieces were intended for use by two or more people! The interactive component of the museum not only makes it more fun for patrons, but also speaks to the intentions of curators or exhibition designers. In our readings about user-centered research, focus has either been placed on the user as an individual or on the community. I would love to learn more about the relationships between users in an information environment. Seeing families and friends interact with one another at the museum was one of my biggest takeaways. One of the more simple illusions was a kaleidoscope with openings at both ends for people to look at one another through. I imagine the effect was much cooler when doing this activity with another person, as when I did it on my own the kaleidoscope did not produce the same effect. The most popular piece on view combines my early point about Instagram potential with social elements. Upstairs there is a room with furniture set up on its side, when people stand in this room they can take photos that create the illusion they are suspended.

As I mentioned I wish I would have attended the exhibition with a friend. As most of the pieces were intended for use by two or more people! The interactive component of the museum not only makes it more fun for patrons, but also speaks to the intentions of curators or exhibition designers. In our readings about user-centered research, focus has either been placed on the user as an individual or on the community. I would love to learn more about the relationships between users in an information environment. Seeing families and friends interact with one another at the museum was one of my biggest takeaways. One of the more simple illusions was a kaleidoscope with openings at both ends for people to look at one another through. I imagine the effect was much cooler when doing this activity with another person, as when I did it on my own the kaleidoscope did not produce the same effect. The most popular piece on view combines my early point about Instagram potential with social elements. Upstairs there is a room with furniture set up on its side, when people stand in this room they can take photos that create the illusion they are suspended.

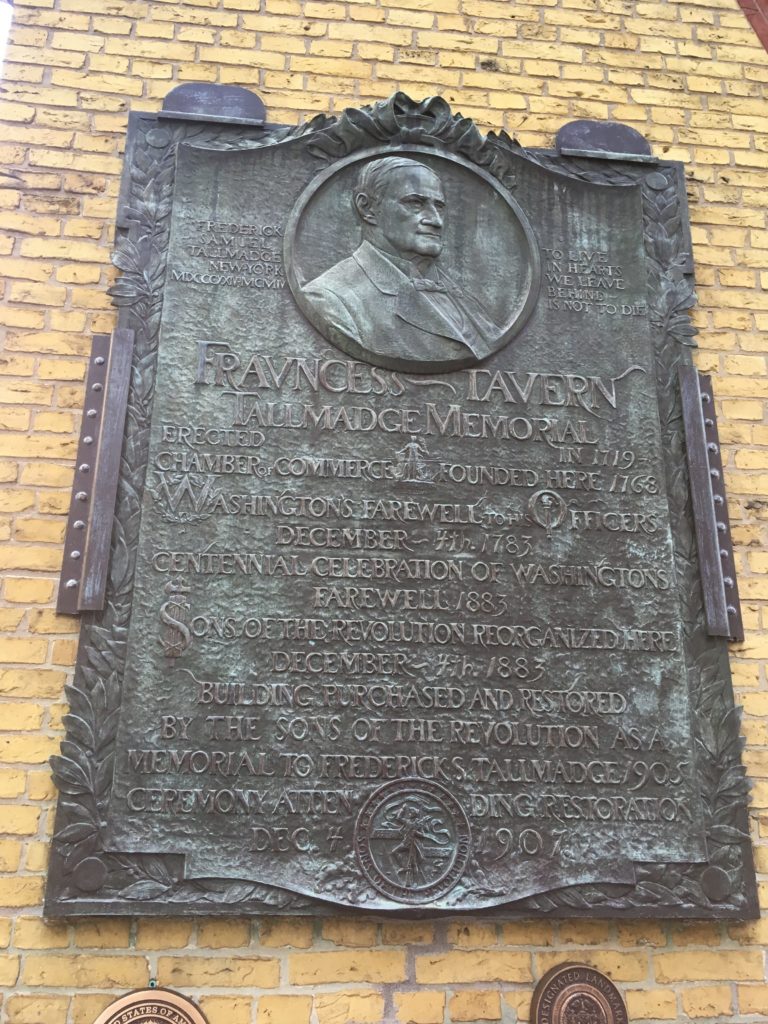

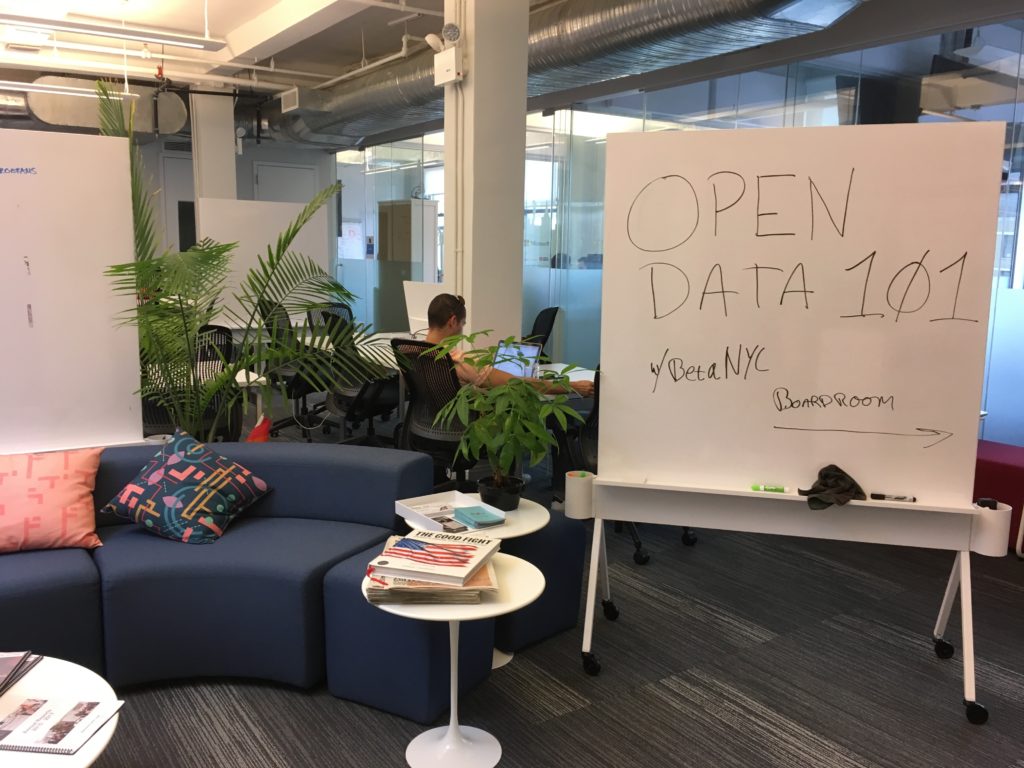

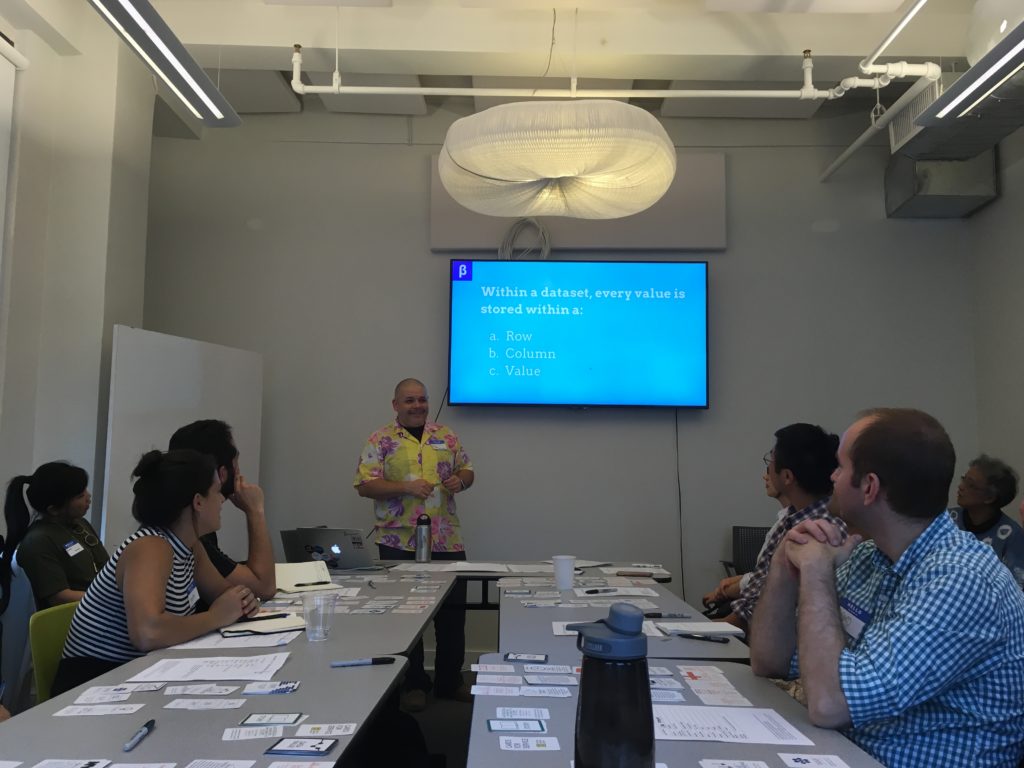

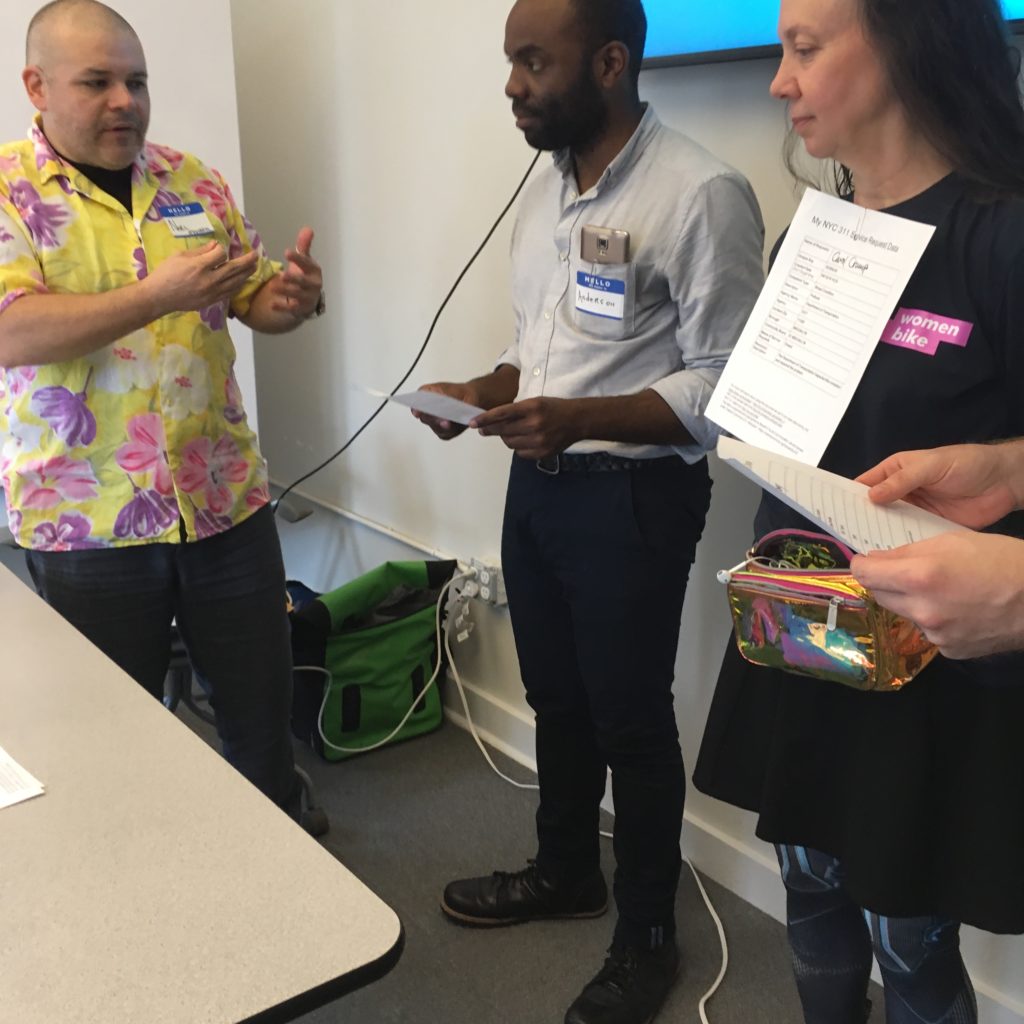

I found this governmental class on

I found this governmental class on

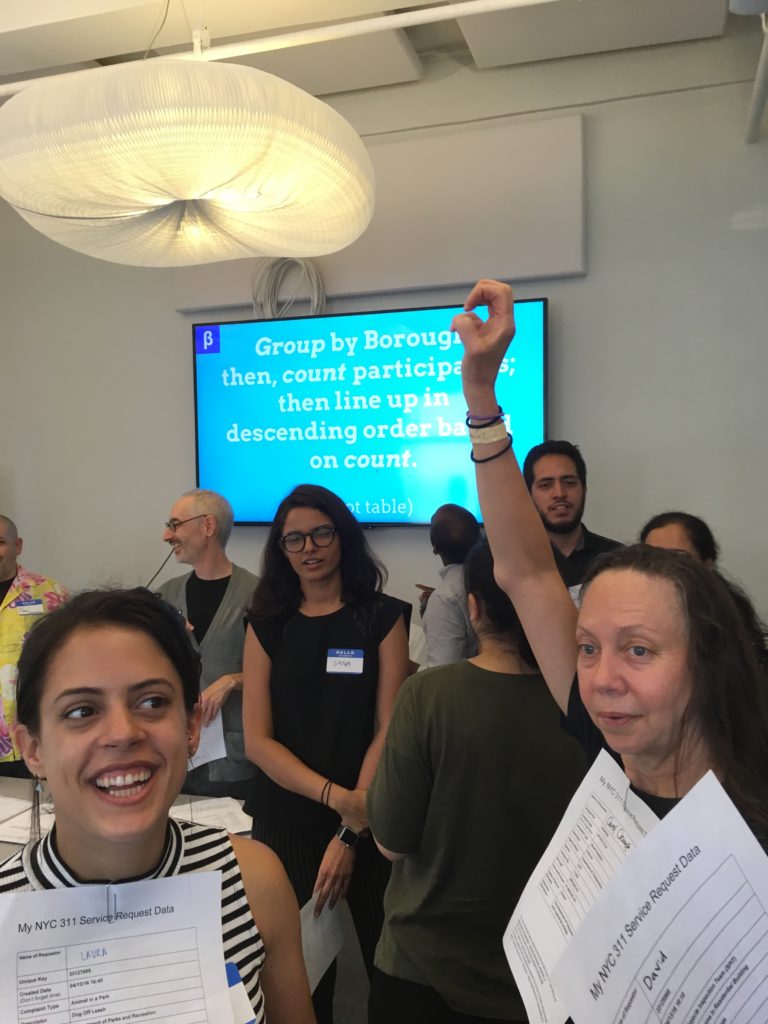

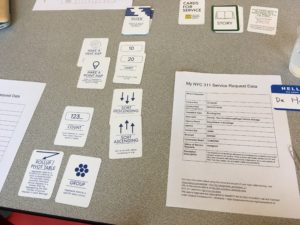

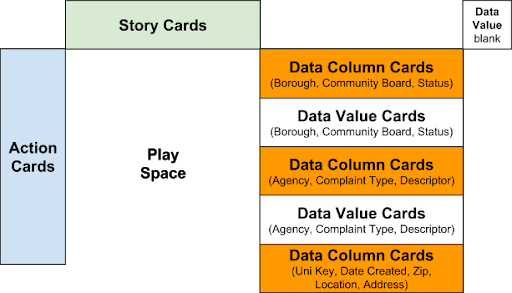

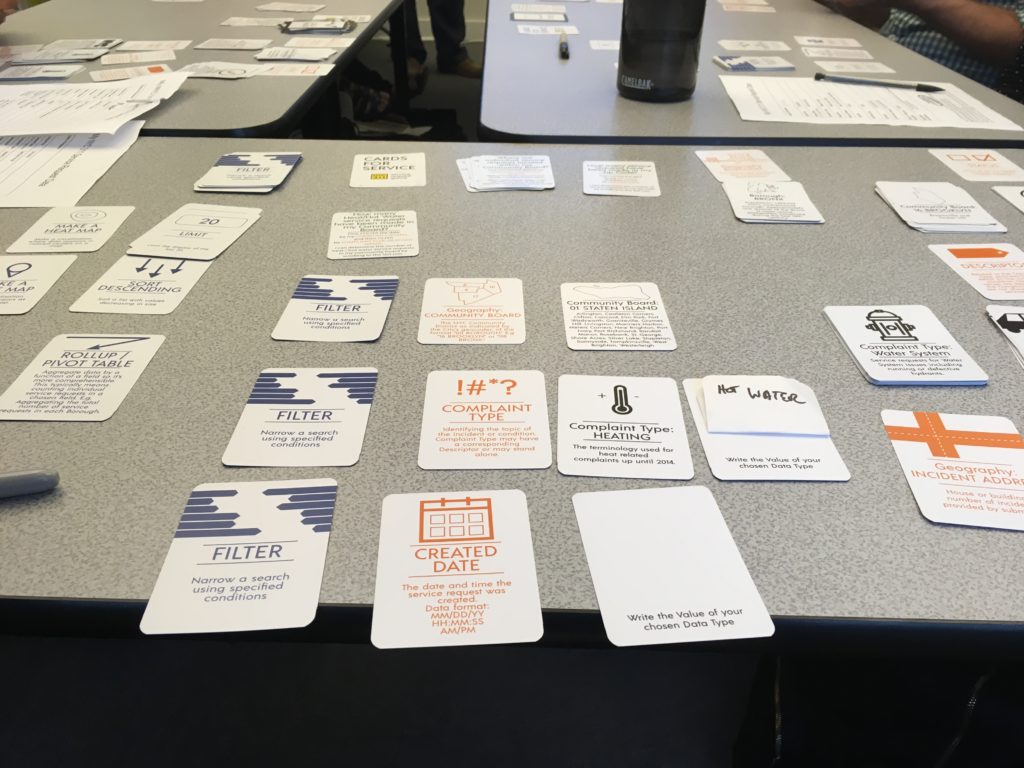

After the icebreaker exercise, everyone get to know each other better and feel closer, as we have been in the same data set and under one task. Each of us act as datum and we served together for a common purpose. We moved to the next activity : Playing with cards!

After the icebreaker exercise, everyone get to know each other better and feel closer, as we have been in the same data set and under one task. Each of us act as datum and we served together for a common purpose. We moved to the next activity : Playing with cards!

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at  phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,

phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,  archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display.

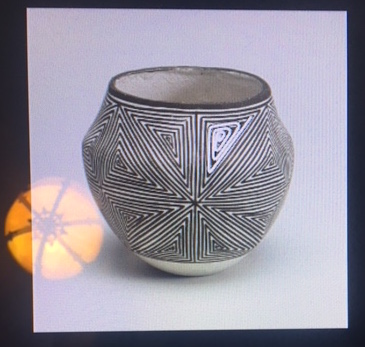

archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display. which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.

which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.