by Jay Rosen

I recently spoke with Jennifer Gellmann, Assistant Division Manager of the Society, Sciences, and Technology (SST) division at Brooklyn Public Library’s (BPL) Central Library. Given my interest in adult services and reference librarianship, I was eager to learn about Jennifer’s work and the day-to-day challenges and rewards of her job.

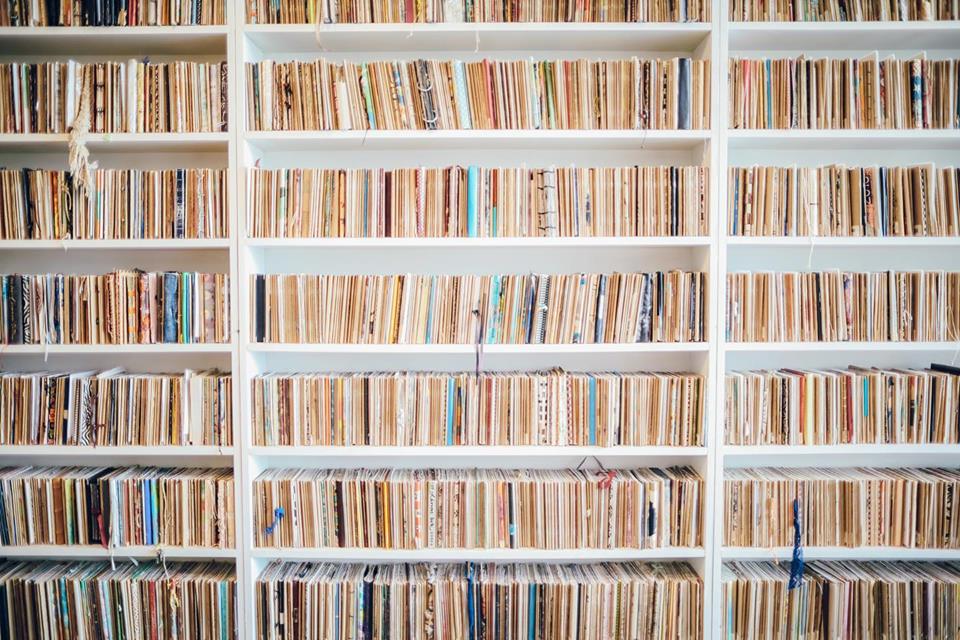

Jennifer began by giving me a brief overview of SST’s scope and collections, and explaining its relationship to the greater Adult Services department at Central Library. SST is staffed by 8-full time “Adult Librarians,” and has a large and diverse physical collection with books on philosophy, psychology, social sciences, science, technology, and industry. SST also has digital collections, special collections containing government publications and legal documents, and a small reference collection.

SST is but one of four divisions making up the Adult Services department at Central Library. Other divisions include “Languages & Literature,” “History, Biography, & Religion,” and “Art & Music.” Related adult-centered divisions include BPL’s Business and Career Center, which offers services for jobseekers and small businesses, the Information Commons, which delivers technology-related programs and services in lieu of a physical collection, and the Brooklyn Collection, a local history archive. BPL’s Central Library is also home to an Adult Learning Center, which provides ESOL classes, test prep, and related educational services to adults. In Jennifer’s view, the various divisions and distinctions among adult service oriented departments are “unnecessarily complicated” and a vestige of prior administrations. For the most part, these departments stand alone, with little inter-departmental communication and collaboration (more on this later).

Jennifer described her role as involving a combination of supervisory, administrative, and public facing duties, with the ratio among these tasks varying depending on particular staffing and library needs. However, she did emphasize that public service is the most significant aspect of her job and the work of her department more generally, with all other responsibilities following from this priority.

Public service duties in SST include working at its reference desk and contributing to virtual chat and email reference services. When I asked about the typical information needs of her patrons, Jennifer told me the “vast majority” of patrons visiting SST are looking for a book on a particular topic. She pushed back on the notion of print being less important in today’s digitally connected age, despite circulation statistics dropping slightly each year.

For the most part, SST is able to successfully meet patron requests, but Jennifer did mention a couple of common issues her department runs into. For one, certain popular books are always in demand to an extent that BPL can’t accommodate. This means patrons often have to place holds and wait several weeks to get materials they need. SST also receives occasional requests for textbooks, but does not purchase them for their collection; as a result, they have to refer patrons to local universities and academic libraries. Despite having one of Central Library’s most expansive physical collections, “you can’t make everybody happy.”

Contrary to many branch libraries that serve fairly defined and specific local communities, Jennifer explained that Central Library serves people from all over Brooklyn. As a result, SST does not serve any one particular demographic. Jennifer emphasized that her work experience varies from branch library service in a couple important ways. For one, there is a great deal of segmentation between different departments at Central Library, with many patrons never stepping foot in the SST division. Because of this, Jennifer’s staff is less familiar with their information needs, which is usually more apparent in smaller branch libraries. In addition, Jennifer explained that branch library staff tend to “wear a lot of hats”, whereas staff at Central Library by and large have a narrower set of responsibilities.

Jennifer was refreshingly honest when describing the challenges of her work. In her view, SST’s primary public service challenge is dealing with the anger and confusion of patrons with undiagnosed and untreated mental illness. “It’s a problem no one has really solved yet,” she told me. Though her staff takes a patient and tolerant approach in these moments, and does their best to regard every request as legitimate, “there’s only so much we can do.” And while SST staff occasionally refers homeless patrons to local service agencies, they choose not to refer mentally ill patrons due to their lack of expertise with mental health issues. Interestingly, BPL hired a full-time social worker a few years ago to help respond to this need, but are currently without one. Until a new social worker is hired, Jennifer and her staff will continue to be seen by some patrons as “de facto social workers,” without the necessary training, expertise, or support. From what I have heard, this appears to be a major unsolved problem for many public-facing library staff around the country.

In further describing the challenges of her job, Jennifer highlighted a general lack of communication between higher administration and the rest of BPL’s staff. I witnessed the same dynamic firsthand during my time at Cleveland Heights Public Library system, and in Jennifer’s opinion this problem plagues most other larger library systems. Though I’m sure it’s easier said than done, I find it both strange and deeply ironic that institutions built to efficiently organize and distribute information suffer from such poor inter-departmental communication.

Jennifer also acknowledged the difficulties of finding and retaining good staff on a limited budget. As she put it, “it’s hard to make a life and have a family in New York City on a particular salary level.” This unfortunate fact this has led to a sharp distinction between “lifers” (Jennifer’s term)— those Jennifer’s age and older who have worked in libraries for decades and live with relative financial stability — and younger staff who are unable or unwilling to commit to the field indefinitely for financial reasons.

Though very frank about the challenges of her position, Jennifer expressed a very clear enthusiasm for her work. She described the main benefits of her job as providing good public service and helping people locate materials that are meaningful to them. Jennifer also expressed contentment with working in “middle management,” citing the mix of public service, committee participation, and administrative roles inherent to her work, as well as the increased “headaches” that seem to come as one moves higher up in library administration.

Significantly, Jennifer told me that the information needs of her patrons have remained relatively stable over time, with the main change being a gradual decline in “reference ready” questions. Erik Bobilin, an Adult Librarian at SST I briefly spoke with, spoke to a more general decline in reference transactions in his experience, likely due to the ease of independently using information technologies. However, both Jennifer and Erik claimed that their division still regularly receives open-ended and more involved research-related reference questions.

When I asked Jennifer what qualities she thinks are needed to succeed in adult services, she emphasized soft skills, including communication skills, the ability to work with a wide range of people, a willingness to answer a variety of different questions, and, above all, patience. This last quality is so important “because the patron doesn’t always know what they want,” and so public-facing staff may need to spend significant time interviewing a patron before unearthing their ultimate question.