Jay Rosen

601 Research Paper

“There have been plenty of articles — too many, it seems sometimes — that describe prison libraries, say they are useful as rehabilitative tools, and stop there.” (Barone, 1977)

For decades, a number of prison librarians and researchers have decried the near-total lack of data in their field regarding the impact of prison libraries on incarcerated individuals. In spite of their critiques, the majority of prison library literature remains descriptive in nature and relies more on speculation than empirically valid claims when describing impact. This paper attempts to identify the main reasons why it is so difficult to adequately evaluate the impact of prison library services. Chief among these include the diminishment of prison library services in America following the Supreme Court’s 1995 Lewis v. Casey decision; professional divides and isolation within the field of prison librarianship; the uniquely complex challenges faced by inmates; difficulties inherent in evaluating impact; profound variations in the missions, resources, and institutional contexts of prison libraries; lack of attention towards impact evaluation in foundational prison library guideline documents; and generally inadequate and understaffed prison library facilities.

Following an exploration of these issues, suggestions for strengthening impact evaluation in prison libraries are proposed, including enhanced advocacy efforts towards politicians, funders, and the public; increased partnerships with public libraries; an explicit adoption of the “public library model” by prison libraries; inclusion of library professionals in relevant policy discussions; improved communication between prison librarians and correctional staff; increased collaboration between re-entry efforts, prison education programs, and prison libraries; strengthening of administrative procedures; general clarification of prison library services; extension of relevant public library initiatives to prison libraries (for instance, the Public Library Association’s Project Outcome initiative); and the development of a more robust theoretical context on which to ground subsequent research.

In discussing the challenges prison libraries face, this paper will focus primarily on American state and federal adult correctional institutions with “full service” libraries. This paper will not consider prison law libraries, although many claims made concerning impact evaluation are likely applicable to those environments as well. Perspectives from Denmark, Norway, and elsewhere across the world are also included.

The Value of Evaluation

Given that most prison libraries are underfunded and understaffed, one can hardly fault prison librarians — often the only permanent, full-time, formally-trained staff member in their library — for prioritizing direct service over data collection. In light of this reality, it is at times tempting to ask why impact evaluation matters in the first place, particularly when resources are so scarce and prison librarians’ time so limited. However, impact evaluation shows great promise in regards to ameliorating these very issues. To name a few benefits, improved impact evaluation can help strengthen decision-making, resource allocation, delivery of services, and funding for prison libraries (Lithgow & Hepworth, 1993). While this paper will not attempt to exhaustively defend the importance of impact research, this section will serve to introduce some of its most significant benefits in this context.

Connections have frequently been made between data collection and improved advocacy efforts. Vogel writes, “The odds of maintaining or even expanding the library can be increased by a librarian who represents the library program as a major contributor to the development of the reading and information skills of the entire incarcerated community” (Vogel, 2009). Data reflecting the connection between prison libraries and the development of desirable qualities and behaviors can go a long way in securing potential funding and portraying prison libraries as valuable institutions deserving of attention and support. Compelling reports can be “invaluable” in convincing prison administrators to approve requests for increased budgets and materials as well (ALA, 1992).

In a similar manner, improved data collection helps to ground prison libraries in ongoing discussions and research on re-entry, inmate education, and prison reform more generally. As will be highlighted later, prison librarians likely have a great deal to contribute to these conversations, yet are almost entirely absent from them today.

It is estimated that roughly half the world’s prison population — over 5 and a half million people — use prison libraries in some capacity (UNESCO, 2019). Better evaluating the impact of prison library services will not only provide information on how prison libraries are used today, but also offer opportunities for librarians and researchers to critically assess and refine services going forward.

Most significant, though, is the largely unrealized role prison libraries might play in facilitating successful re-entry and reducing recidivism. The vast majority of inmates in America are ultimately released from prison back into society — some estimates put this figure as high as 95%.[2] This is likely to remain the case for the foreseeable future, as many people incarcerated during the so-called “War on Drugs” continue to be released, and as a growing number of prisons release inmates early in response to budget shortfalls (Stearns, 2004). Though most inmates in America will eventually be released, 43% of them will return to prison at least once (Pew Research Center, 2011)[3]. Better understanding the impact of prison libraries will enable librarians to strengthen their services in order to encourage positive outcomes and lower recidivism rates for this population.

Moreover, improving prison library services will likely improve literacy and education rates for individuals re-entering society, thereby helping to reduce costs associated with higher crime, incarceration, and re-incarceration. These financial benefits would be matched only by the improvements in public safety that result from decreased crime.

In short, improved impact evaluation will strengthen prison library services, thereby increasing their positive potential and providing compelling evidence for their continuation and expansion.

The Mission and Purpose of Prison Libraries Today

Before delving into the particular challenges faced by prison libraries in regards to impact measurement, it is useful to first clarify their primary aims. Prison libraries first emerged in Europe and the United States throughout the 17th century as a means of providing “moral and religious education” to inmates (Garner, 2017). The first prison “librarians” were actually clergymen who dispensed religious books to prisoners in the hopes of encouraging their “spiritual and moral reading and training” (UNESCO, 2019). Under this arrangement, prison library collections consisted entirely of approved religious texts, with books that served primarily to entertain (novels for example) strictly forbidden.

This model of prison libraries persisted through the early 20th century, until the idea of reading for “educational purposes and for emotional, personal and intellectual development” (UNESCO, 2019) began to gain traction. In fact, not until 1970 were prison libraries formally recognized in the United States as institutions promoting “wholesome recreation, direct and indirect education, and mental health” (Lehmann 2011). Today, prison libraries have largely adopted the public library philosophy of promoting information access as an unconditional human right, and have developed policies and collections intended to meet the diverse information needs of their patrons. Their mission has expanded tremendously beyond offering spiritually edifying materials to include providing contact to outside communities, supporting rehabilitative programs, offering information on vocational skills, providing informal educational programming, encouraging self-directed recreational reading, providing access to legal information and the courts, and attempting to generally prepare inmates for re-entry (ASGCLA 1992).

Though the missions and resources of individual prison libraries vary depending on the needs of their patrons and the restrictions and allowances of the correctional facility they are embedded in, most can easily be placed into six of eight roles of public libraries as identified by the Public Library Association (PLA): these include Community Activity Center, Community Information Center, Formal Education Support Center, Independent Learning Center, Popular Materials Library, and Reference Library.

A number of national and international documents guide and govern the development and implementation of prison library services around the world. Commonly cited guidelines include the American Library Association’s (ALA) Library Bill of Rights, Freedom to Read Statement, Freedom to View Statement, and Policy on Confidentiality of Library Records; the Association of Specialized and Cooperative Library Agencies’ (ASGCLA) Resolution on Prisoners’ Right to Read and Library Standards for Adult Correctional Institutions; the Council of Europe’s European Prison Rules; the United Nations’ Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners; and the International Federation of Library Association and Institutions’ (IFLA) Charter for the Reader.

As the missions of prison libraries have expanded, so too have their intended outcomes. Common intended impacts of prison libraries include improved literacy skills, information literacy, and the development of “critical reasoning skills, self-confidence, self-esteem, empowerment, and changed perspectives” (Warr, 2016), as well as the strengthening of hope, motivation, social bonds, and mental health for inmates (Finlay & Bates 2018).

A chief motivation for the expansion of purpose and intended impact in prison libraries is the apparent success of correctional education programs in reducing recidivism rates and promoting successful reentry (Wilhelmus, 1999). But despite a clearer articulation of their purpose and intended outcomes than perhaps ever before, most prison libraries around the world remain plagued by a lack of empirical data testifying to the actual impact of their services. The next section will review the many reasons this is so.

Challenges in Evaluating Impact in Prison Libraries

Librarians and researchers have lamented the scarcity of empirical evidence on the impact of library services on incarcerated users for at least sixty years now. David M. Gillespie’s 1968 analysis of prison library literature describes a prevailing overreliance on description over evaluation of prison library services (Gillespie, 1968), and the American Friends Service Committee similarly declared in 1971 that prison library literature lacks “credible scientific data on the effectiveness of correctional treatment program” (Barone 1977), with most programs determining their effectiveness not through rigorous research but rather “speculation.” These early concerns appear to have been largely ignored, and most in the field have not yet heeded calls to provide empirical data to buttress claims of positive impact. The situation has so little improved that one can scarcely tell whether particular pleas for increased research and data collection were published fifty years ago or in 2018.

Why has this remained such a pervasive and largely unaddressed issue? What barriers prevent librarians and researchers from evaluating the impact of prison library services on inmates? This section identifies a number of distinct but overlapping problem areas.

Difficulties in Evaluating Impact

Notwithstanding the particular challenges faced by prison libraries, it is notoriously difficult to compellingly demonstrate causal relationships between particular factors and particular outcomes. Because there are so many forces at play in any individual’s life in a given moment, it is incredibly difficult to isolate any one aspect and argue for its particular impact. This fact helps explain why so many accounts of prison library impact rely on anecdotal evidence and largely unsubstantiated claims. Though it is tempting to make connections between library use and improved outcomes for inmates based on sentiment and observation alone, “the reason for an inmate’s success or failure is probably more complicated, [and is] produced by many factors, including criminogenic needs, risk principles, and the complicated interaction between an inmate and their institutional environment” (Stearns, 2004). Were prison librarians and researchers to dramatically improve impact evaluation tomorrow, it would remain exceedingly difficult to make conclusive, causal claims about the impact of particular library resources on particular inmate outcomes. As the esteemed social scientist Raj Chetty puts it, “there are so many things data may be trying to say” (Cook, 2019).

Both quantitative and qualitative data present particular challenges in regards to impact evaluation. Though quantitative data is typically more tangible and easily collected than qualitative information, it is frequently misleading and limited. Ratios of library materials to inmates were often cited as a measure of success for prison libraries, despite the fact that prison library collections were mostly “outdated, little used, and sometimes inaccessible” (LeDonne, 1977). Other “hard data” including circulation statistics, number of patron interactions, and library program attendance, for example, likewise say very little about the quality of a patron’s experience, and can inadvertently foster inaccurate narratives.

A greater consensus exists these days regarding the importance of gathering qualitative data to demonstrate impact. However, qualitative data presents its own set of challenges. For one, it is generally difficult to assess phenomena related to behaviors, attitudes, and other aspects of “human experience and development” (Finlay & Bates, 2018). Though many advocate for prison libraries on behalf of their ability to provide solace and “generate a feeling of normalcy” (UNESCO, 2019) for their users, it is hard to capture these invisible characteristics through data collection. This is true of many of the other behaviors prison libraries seek to encourage, including improved self narratives, identity development, and increased confidence pursuing self-directed learning opportunities (Warr, 2016). Is it possible, though, to provide objective evidence of subjective changes?

Impact evaluation research also suffers from conceptual, methodological, and management issues. Conceptual issues relate “to the definition of library effectiveness, to who judges effectiveness, and to the definition of information needs and uses” (Vanhouse, 1989). Methodological issues instead relate “to the data collection methods, sampling, and statistics” used, while managerial issues “address the appropriate use and interpretation of measurement data” (Vanhouse, 1989). These issues spur complex and ambiguous questions which lack a “single, operational definition” (Vanhouse, 1989).

Other issues related to impact measurement in prison libraries include the fluidity of user needs, attempts by inmates to conform to the measures of particular studies, and the fact that most inmates are not followed up with by researchers after their release (Barone, 1977).

Taken collectively, these factors encourage caution when gathering and assessing data in prison libraries:

“While we may be able to construct abstract models of the relationship between library actions and output measures, in practice the complexity of the library and its environment interferes with attempts to understand and manipulate output measures…They should be used with caution and an understanding of their limitations” (Vanhouse, 1989).

Recent research similarly testifies to the challenges of identifying “an appropriate means of measuring outcomes and evaluating change” (Behan, 2014) in as unique and complex an environment as prison. This is not to suggest that such attempts cannot and should not be made. Rather, one should be mindful of the specific limitations, challenges, and pitfalls inherent to evaluating impact.

Lack of Research and Attention

With few exceptions, documents offering policies and guidelines for prison libraries devote marginal attention to assessing and evaluating prison library services. IFLA’s Guidelines for Library Services to Prisoners provides one sentence on measuring impact following their 94 distinct recommendations, only suggesting that libraries should conduct performance evaluations every “3-5 years.” UNESCO’s Books Behind Bars report likewise contains only a few words on impact evaluation. The same is true of prison library literature more broadly. Clark and MacCreaigh’s Library Services to the Incarcerated offers only a two page appendix on “performance measures,” and many other works refer to data collection and performance measurement in passing or as a brief aside.

That these otherwise comprehensive, thoughtful, and well-researched works offer only a few pages (or words) on impact evaluation is extremely telling of the lack of attention devoted to this issue. Impact evaluation is deserving of more than lip service, and organizations and individuals already invested in relevant research, advocacy efforts, and policy discussions have a role to play in more clearly articulating and developing guidelines on impact evaluation.

A Highly Decentralized Field

There exists a great deal of variation in regards to how individual prison libraries are established and embedded in particular correctional facilities. Some prison libraries belong to their institution’s education department, others exist within rehabilitation-centered departments, and still others exist independent of any formally defined correctional department. In addition, the degree of cooperation between prison libraries and nearby public library systems varies tremendously, with some libraries collaborating extensively with one another and others have no connection whatsoever. Every prison library, then, is unique in both its operation and relationship to relevant institutions.

Unsurprisingly, prison libraries differ remarkably in regards to their missions as well. As a result, it is not uncommon for confusion and disagreement to arise regarding the purpose and structure of a prison library: Does the library exist primarily for recreation? To grant access to legal materials? To rehabilitate or “reform” inmates? To serve as a public library surrogate?

Of course, variation amongst prison libraries is a natural reflection of their unique user groups, resources, and restrictions. However, this decentralization complicates efforts to create useful and widely applicable guidelines for impact evaluation in prison libraries.

Diminishment of Prison libraries

The precarious and diminished status of prison libraries in America is also central to understanding the general lack of research and data in this field.

The Supreme Court’s 1995 Lewis v. Casey decision dealt a powerful blow to prison libraries across the United States. The decision affirmed prisoners’ constitutional right to access the courts, but further declared that this right is not violated when prisoners lack “legal research facilities or legal assistance” — so long as prisoners are not “substantially harmed” by their absence. Though this decision primarily affected prison law libraries, it was widely seen as a reflection of prison libraries’ diminished importance in the eyes of the courts (Vogel, 2009).

Other factors undermining prison libraries in America include the embrace of high security “Supermax” facilities, a trend towards prison privatization, the economic recession of 2008 (leading to the freezing or elimination of many prison librarian and educator positions (Lehmann 2011)), the introduction of re-entry programs in isolation from prison library programs, and the continued funding of “faith based” initiatives that compete with prison libraries for limited funds (Vogel, 2009).

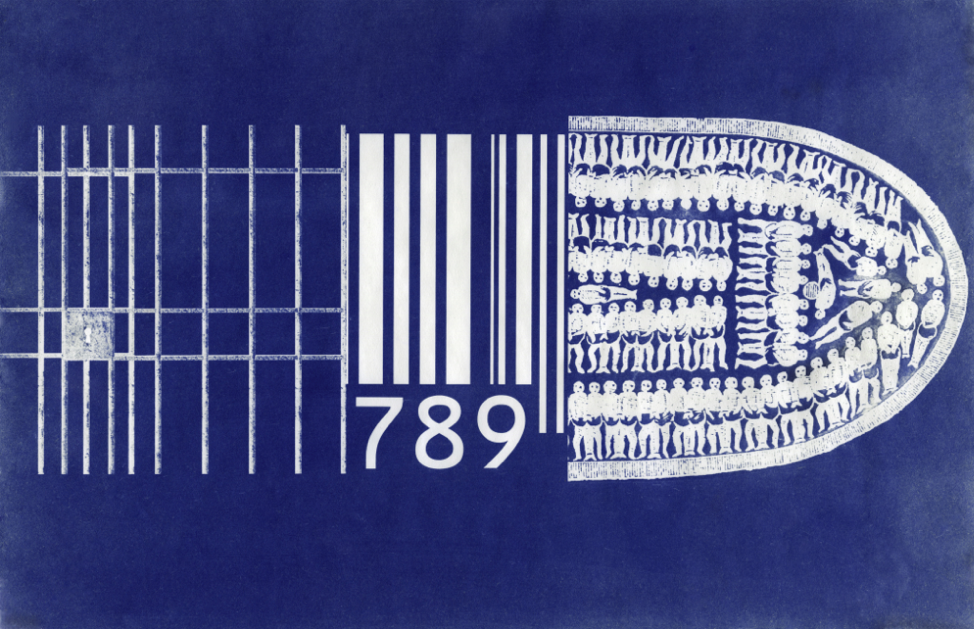

On a deeper level, prison libraries suffer from a punitive approach to incarceration on judicial and congressional levels. This approach — which emphasizes punishment over rehabilitation and desistance — also finds expression in the mass media, with the result that most Americans are “bombarded with fictionalized and docu-images of prison, prisoners, and prison life,” images which tend to represent incarcerated people as sinister, hyper-violent sociopaths (Vogel 2009). Significantly, these depictions often represent prison libraries as spaces where inmates become further radicalized, encounter dangerous ideas, or hatch criminal plans (Stearns, 2004).

Lack of advocacy for prisoners and prison libraries both results from and exacerbates these caricaturized, negative portrayals. The ALA has come under fire for its insufficient lobbying efforts on behalf of incarcerated library patrons, with some arguing that the organization forgets — or refuses to acknowledge — “that prisoners are a library constituency too” (Vogel, 2009). In the absence of sustained public advocacy from larger library organizations, prison libraries are vulnerable to a lack of recognition and support from prison administrators, a situation that further contributes to their diminished state (Garner, 2017).

Further, prison libraries are neither guaranteed nor expressly prevented by any “federal laws, constitutional provisions, or Supreme Court decisions” (Vogel, 1997). As a result, prison libraries exist in a highly ambiguous legal gray area. Advocacy on behalf of increased legal protections for prison libraries might go a long way towards addressing the lack of empirical data in the field.

Recent mainstream discussions about the devastating and disproportionate impacts of mass incarceration perhaps signal a change in our public attitudes towards prisons and their inhabitants. At the least, there seems a growing recognition that the majority of American prison conditions are not conducive to any form of rehabilitation (some research suggests the opposite, in fact). Nonetheless, the above examples demonstrate that hostile perceptions of prisoners and prison libraries lead to their diminishment and complicate efforts to evaluate their impact on one another.

Inadequate and Understaffed Facilities

The generally inadequate status of most prison libraries goes a long way in explaining the lack of substantive research in the field. Most accounts of prison libraries make reference to the financial challenges they face. “The library program is often the lowest in priority, usually lacking an adequate budget, facilities, personnel, and moral support from the administration and custodial staff” (Barone, 1977). More recent scholarship testifies to the persistence of these issues; “As a rule, prison libraries are insufficiently funded” (Šimunić, 2016) and remain “lowest on the priority list” of state library budgets (Vogel 1997).

Among other negative outcomes, the impoverished state of prison libraries results in extremely understaffed facilities. As previously mentioned, prison librarians are often the only permanent, professionally trained employee of their library, and are commonly assisted by inmates who work part-time or volunteer. Prison librarians are thus tasked with carrying out a wide range of tasks and frequently struggle to “develop user programs and activities beyond the very basic services” (UNESCO, 2019). It is worth noting, too, that these librarians often work in professional isolation and in a highly regulated, restricted, demanding, and sometimes stressful environment. Prisons further represent a particularly difficult and unfamiliar setting for most librarians by requiring “restricted access to information, high levels of censorship, and little to no access to information technology and other resources” (Finlay & Bates, 2018).

As if these challenges were insufficient, prison librarians are charged with the near-Herculean task of meeting “the information and diverse reading needs of a large multicultural community whose members have involuntarily been forced to live together” (ALA, 1992). In an environment in which most librarians are simply trying to keep things afloat, it is easy to understand the near-complete absence of empirical data describing the impact of their services.[4]

In addition, many prison libraries are staffed by correctional employees who lack expertise and training in delivering library services (Šimunić, 2016). Although the IFLA advocates staffing prison libraries with professionally trained librarians, there is little evidence of widespread adherence to this recommendation. It is therefore not uncommon for prison libraries to be managed entirely by prison officers and inmates, or at least for their day-to-day operations to fall under their purview. Of course, this arrangement is better than nothing, and is a reflection of the larger lack of care and support offered prison libraries today. Nonetheless, this arrangement represents a “major obstacle to future development and to the ultimate goal of building truly professional prison libraries” (Lehmann, 2011).

Prison librarians also commonly lack computers and other technologies typically available in most other kinds of libraries. This complicates the tracking of basic internal operations and makes the systematic collection of empirical data immensely more difficult. In a similar vein, prison libraries are excluded from the Institute of Museum and Library Services’ (IMLS) Library Services and Technology Act, which allocates funds to be used for expanding services and accessing information resources (Lehmann, 2011).

Finally, prison librarians frequently lack autonomy and struggle for respect and understanding from other correctional staff. As Lehmann and Locke write, “in any profession that involves working with special populations, a narrow focus often develops in which the worker views that population only within the values and theories of that particular discipline” (Lehmann & Locke, 2005). It goes without saying that librarians and most other correctional employees operate under quite different and perhaps incompatible goals and principles. In the context of prison libraries, the “narrow focus” of each camp usually manifests in perceptions of librarians as naïve, easily manipulated “do-gooders” and correctional staff as apologists for a callous and oppressive system. It is important to note that neither view is “correct” or even useful; on the contrary, these perceptions prevent librarians and correctional staff from productively collaborating and understanding the other’s priorities and approaches. While this kind of relationship surely does not exist in every prison, it is a commonly referenced dynamic and a further obstacle to cultivating an atmosphere of trust, shared understanding, and mutual respect in prison libraries.

In sum, disregard and lack of sufficient investment by library associations, politicians, funding institutions, and many correctional staff results in prison libraries that are often grossly underfunded and understaffed. This unfortunate reality makes the delivery of library services the primary aim of most prison librarians (quite reasonably so), and limits their ability to systematically evaluate the impact of their services.

Professional Divides and Isolation

Another factor contributing to the dearth of prison library research is the siloing of prison librarianship on multiple levels. Despite a surge of interest regarding inmate re-entry, relevant research and literature by and large fails to acknowledge the importance of skills encouraged by libraries (information literacy, for example) on the process of returning to society. Similarly, there is “an eerie lack of awareness about digital literacy and job preparation…in public policy guidelines” for re-entry programming” (Vogel, 2009). As a result, prison librarians are left “on the sideline” of most re-entry debates (Vogel, 2009). Librarians and library advocacy groups are similarly left out of most policy discussions regarding prisoners (UNESCO, 2019), who are themselves excluded from most education discourse (Vogel, 2009).

A disconnect exists, too, amongst public and prison libraries. Though many public and prison libraries collaborate with one another to share staff and resources, no central guidelines exist to formalize this partnership. Initiatives developed by public libraries in regards to impact evaluation are therefore often not inclusive of prison libraries, or are never shared with them.[5]

Finally, even if better communication between public and prison libraries was achieved, the LIS field itself has been called “isolated in considering the common problem of organizational effectiveness,” failing to draw on relevant research from the public and service sectors (Cameron & Whetten, 1983).

Seen in this light, prison libraries and prison librarians are isolated branches of an already isolated field.

A Uniquely Challenging User-Group

Though it is difficult to measure impact with any user group, it is perhaps more so with a population facing a disproportionate degree of personal, economic, educational, and social problems. On the whole, incarcerated individuals have lower levels of education and higher rates of illiteracy, suffer more from substance abuse and mental illness, and come from disadvantaged social and economic backgrounds at significantly higher rates than non-incarcerated populations. In addition, many incarcerated people in America struggle with technology and do not speak English as their first language (Lehmann, 2011). As a result of these disproportionate disadvantages, they are frequently considered a “unique user group with special needs” (Lehmann, 2011).

These problems disproportionately affect inmates even in countries with prison systems considered more modern and humane; Scandinavian inmates likewise experience the same personal, social, and economic problems at higher rates than most civilians in these countries (Ljødal, 2011). This fact raises broader questions about the links between membership in disadvantaged minority groups and incarceration. For the purpose of the paper, however, these examples are raised in order to demonstrate the difficulties prison librarians face in attempting to meet the diverse information needs of underserved individuals facing often immense challenges in a number of areas.

Improving Impact Evaluation in Prison Libraries

Given this multitude of challenges, what can be done to improve the measurement of prison library services?

To begin, most prison libraries would do well to clarify and formalize their primary services and objectives. This clarification will help determine an initial sense of overall effectiveness, and will indicate which measures are important to track. “Once roles have been selected and programs developed to support those roles, measurement of the quality of the library service becomes more exact” (ALA, 1992). Clarifying services and objectives through written policies and informal discussions might also bring attention to previously unacknowledged funding sources.

Dissolving professional and institutional barriers can also go a long way in empowering prison librarians to better measure the impact of their services. Unanimously adopting the “public library model” will help prison libraries align with “the professional standards and ethics of the wider library profession” (Finlay & Bates, 2018). This alignment has occurred in Denmark and other Scandanavian countries, resulting in enhanced cooperation and greater access to resources and support for prison librarians (Ljødal, 2011). Increased communication and support can also be sought out between LIS professionals, researchers, and correctional staff in order to reduce hostility and “produce empirical studies that not only help the library…but can enrich both the fields of librarianship and criminology” (Stearns, 2004).

Prison libraries can also play an increased role in relevant policy discussions amongst stakeholders and the judicial system, and can seek to establish “national and regional prison library networks and associations” (UNESCO, 2019). This would result in the creation of policy documents and practical guidelines informed by prison librarians and reflective of their ongoing experiences. Consulting prison librarians throughout the prison construction process would also lead to the establishment of optimally designed and functional library facilities; Norway is one country which regularly consults library professionals when constructing and renovating prisons (Ljødal, 2011). All of these suggestions will serve to increase representations of prison librarians in valuable processes and discussions, contributing to the creation of an atmosphere more conducive to impact evaluation.

Similarly, increased connections can be made between re-entry efforts and prison libraries. In recent years, many state prisons have introduced re-entry curricula that include classroom instruction and assignments related to personal development, education opportunities, and financial literacy, among others (Vogel, 1997). Prison libraries have a great deal to contribute to these programs and to the fields of re-entry research and inmate education more generally; “We argue for wider inclusion of the library in contemporary research on prisoners’ experiences of learning” (Finlay & Bates, 2018).

Public library initiatives intended to improve impact evaluation can also be adapted and extended for prison libraries. PLA’s Project Outcome initiative offers standards and tools — including survey management options, data visualizations, training resources, and custom report builders — to be used in measuring the outcomes of public library services and programs. Furthermore, data generated through this project can be shared, viewed, and discussed online, allowing library professionals to see how their particular results compare to state and national averages. Since its introduction in 2015, Project Outcome has been widely praised and expanded for academic library settings. There is no apparent reason why this initiative cannot be tailored for prison libraries as well.

The development of a more expansive and robust theoretical context for prison libraries will provide a strong foundation on which subsequent research and data collection can occur; “A larger body of empirical evidence, grounded in relevant theoretical constructs, is needed to truly understand the role of the library in the lives of prisoners” (Finlay & Bates, 2018). The development of “sound ideas” regarding the function and goals of prison libraries will also provide clarity and a greater degree of autonomy to prison librarians. Holistic theoretical models for prison libraries have been proposed in recent years and center on desistance research, criminogenic factors, and insights from the fields of psychology, education, and medicine, among others (Finlay & Bates, 2018). Situating the theoretical context of prison librarianship in relevant adjacent fields will encourage “interdisciplinary examinations of inmates and how prison affects them” (Stearns, 2004), and offer insights that could not be gained in isolation.

Finally, more aggressive and sustained advocacy can be pursued in order to improve the public perception and financial status of prison libraries. Successful advocacy efforts aid in creating a culture that recognizes prison libraries as “vital contributors to the field of corrections” (Stearns, 2004) and highlight their role in promoting “recreational pursuits, education, literacy improvement, and socialization” (Ljødal, 2011). As previously discussed, advocacy is also central to increasing visibility among funders, stakeholders, and others “responsible for increasing noncustodial budgets” (Vogel 2009).

Conclusion

Prison libraries face significant challenges in regards to evaluating the impact of their services. At the same time, numerous reforms can be pursued in the short and long term in order to begin enhancing and formalizing data collection processes. Improving the measurement of prison libraries services will benefit inmates, library and correctional staff, researchers looking to better understand the role prison libraries play in facilitating re-entry, and anyone seeking to convince funders, politicians, and the public of prison libraries’ largely unrealized value and potential.

Bibliography

American Correctional Association, & Freedman, E. I. (Eds.). (1950). Library manual for correctional institutions: A handbook of library standards and procedures for prisons, reformatories for men and women and other adult correctional institutions. New York.

Association of Specialized and Cooperative Library Agencies (Ed.). (1992). Library standards for adult correctional institutions, 1992. Chicago: ALA.

Barone, R. M. (1977). DeProgramming Prison Libraries. Special Libraries.

Behan, C. (2014). Learning to escape: prison education, rehabilitation and the potential for transformation. Journal of Prison Education and Reentry, 1(1), 20-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.15845/jper.v1i1.594

Books beyond bars: The transformative potential of prison libraries—UNESCO Digital Library. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2019, from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000369835

Clark, S., & MacCreaigh, E. (2006). Library services to the incarcerated: Applying the public library model in correctional facility libraries. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited.

Collection Development and Circulation Policies in Prison Libraries: An Exploratory Survey of Librarians in Us Correctional Institutions. (2012). Library Quarterly, 82(4), 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1086/667435

Conrad, S. (2017). Prison librarianship policy and practice. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Cook, G. (2019). Raj Chetty’s American Dream—The Atlantic. Retrieved October 20, 2019, from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/08/raj-chettys-american-dream/592804/

Coyle, W. (1987). Libraries in prisons: A blending of institutions. Greenwood Press.

Dalton, M. (2013). There is a Lack of Standardization in the Collection Development and Circulation Policies of Prison Library Services. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 8(2), 248–250. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8R611

Finlay, J., & Bates, J. (n.d.). What is the Role of the Prison Library? The Development of a Theoretical Foundation. 20.

Hughes, T. & Wilson, D.J. (2011). Reentry trends in the U.S. Retrieved November 25, 2019 fromhttps://www.bjs.gov/content/reentry/reentry.cfm

IFLA — Guidelines for Library Services to Prisoners. (n.d.). Retrieved November 21, 2019, from https://www.ifla.org/publications/ifla-professional-reports-92

LeDonne, M. (1977). Survey of Library and Informational Problems in Correctional Facilities: A Retrospective Review. LIBRARY TRENDS, 18.

Lehmann, V. (2003). Planning and Implementing Prison Libraries: Strategies and resources. Retrieved October 8, 2019, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/034003520302900406

Lehmann, V., & Locke, J. (2005). Guidelines for library services to prisoners (3rd ed). The Hague: IFLA Headquarters.

Lehmann, V. (2011). Challenges and Accomplishments in U.S. Prison Libraries. Library Trends, 59(3), 490–508. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2011.0001

Lehmann, V. (2011). Library and information services to incarcerated persons: Global perspectives. Baltimore, Md.: The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

Lewis v. Casey, 518 U.S. 343 (1996). (n.d.). Retrieved from https://supreme.ustia.com/cases/federal/us/518/343/.

Lithgow, S. D., & Hepworth, J. B. (1993). Performance measurement in prison libraries: Research methods, problems and perspectives. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 25(2), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/096100069302500202

Ljødal, H. K., & Ra, E. (2011). Prison Libraries the Scandinavian Way: An Overview of the Development and Operation of Prison Library Services. Library Trends, 59(3), 473–489. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2011.0010

Rada Europy. (2006). European prison rules. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publ.

Rubin, R. J., & Suvak, D. (1995). Libraries Inside: A Practical Guide for Prison Librarians. McFarland and Company, Inc.

Shofmann, F. (2016). Performance Measurement. Retrieved November 21, 2019, from Public Library Association (PLA) website: http://www.ala.org/pla/initiatives/performancemeasurement

Šimunić, Z., Tanacković, S. F., & Badurina, B. (2014). Library services for incarcerated persons: A survey of recent trends and challenges in prison libraries in Croatia. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 48(1), 72–89. doi: 10.1177/0961000614538481

State of Recidivism (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/0001/01/01/state-of-recividism.

Stearns, R. (2004) The Prison Library: An Issue for Corrections, or a Correct Solution for Its Issues? Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 23:1, 49-80.

UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/pdf/criminal_justice/UN_Standard_Minimum_Rules_for_the_Treatment_of_Prisoners.pdf

Vanhouse, N. (1989). Output Measures in Libraries. Library Trends, (38): 2. University of Illinois.

Vogel, B. (1997). Bailing out Prison Libraries: The Politics of Crime and Punishment Frame the Crisis in Prison Library Service. Library Journal, (19): 35.

Vogel, B. (2009). The prison library primer: A program for the twenty-first century. Scarecrow Press.

Warr, J. (2016). Transformative dialogues: (Re)privileging the informal in prison education. Prison Service Journal, 225, 18-25.

Whetten, D. A., & Cameron, K. S. (1991). Organizational effectiveness: a comparison of multiple models. San Diego (California): Academic Press.

Wilhelmus, D. W.

(1999) A new emphasis for correctional facilities’ libraries. Journal of Academic Librarianship,

25(2), 114-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(99)80009

[1] The term “forgotten field” was first used by Suzanna Conrad in her 2017 work, Prison librarianship policy and practice. Conrad, S. (2017). Prison librarianship policy and practice. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

[2] This according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ 2011 Reentry trends in the U.S. report. Hughes, T. & Wilson, D.J. (2011). Reentry trends in the U.S. Retrieved fromhttps://www.bjs.gov/content/reentry/reentry.cfm

[3] https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/0001/01/01/state-of-recidivism

[4] It is worth noting, too, that many librarians have little to no training in statistics, data analysis, and performance measurement (Vanhouse, 1989). This presents somewhat of a catch-22, as outside researchers have been shown to influence behavior and shape experimental results in undesired ways (Lithgow & Hepworth, 1993).

[5] Take, for example, the Public Library Association’s (PLA) Output Measures for Public Libraries — a set of standards “widely used in the public library community” (Vanhouse, 1989) — as well as PLA’s more recent Project Outcome initiative. While the latter was recently expanded for academic library settings, there is no indication that the PLA has considered adapting these resources for prison libraries.