What is NYC Media Lab’18

Every year, NYC Media Lab hosts a summit where investors, professionals and students come together to present projects and ideas. This year’s NYC Media Lab Annual Summit was held at The New School on September 20th. There were thought-provoking debates, hands-on workshops and 100 demos. Attendees appeared thrilled to explore the future of digital media innovation.

Keynote speakers

Keynote speakers were Thomas Reardon, CEO and CO-Founder of CTRL-Labs, and Maya Wiley, Senior Vice President for Social Justice and Co-director, Digital Equity Lab The New School.

Reardon’s talk was the highlight of the event. It was very engaging and insightful. Reardon has received his PhD in Neuroscience from Columbia University. The core idea of his discussion was very similar to what Don Norman said in his book “The Invisible Computer”. Norman discusses what computers are good at and what humans are good at. He then suggests that technology is designed and people are being asked to conform to the needs of the computer. Although it is useful to take advantage of the strengths of the computer, this only works if the machine adapts itself to human requirements. Reardon presented a technological solution to issue Norman discussed in his book. He discussed the huge gap between human input and human output. How neural interfaces can solve the output delay problems. He explained that muscles are causing delays in the output, and if we manage to read the mind, we can eliminate muscles from the process. He argued that capturing intention, not just motion and making it work, is the future. He also mentioned that this technology will help people with motor neuron diseases. After hearing his ideas, I am very excited to learn more about neural control and robotics.

Wiley is a nationally renowned expert on racial justice and equality. She discussed that technology is driving policies and urged entrepreneurs to model their business to help low-income households. She highlighted the difficulties that low income, coloured neighbourhoods face. Her talk was insightful and made me think about the effects of technology on underprivileged populations. As suggested by Jentery Sayers that blending together collaboration, experimental media, and social justice research can bring a new trajectory for American and cultural studies.

Project Showcase

Seven innovative startups presented their ideas and prototypes. Some notable projects that inspired me were:

Ovee

Ovee is a project by Jane Mitchell and Courtney Snavely. It is a platform that creates a community that supports women as they navigate reproductive health issues. Ovee is my favourite project because I can relate to the problems it is addressing.

Let’s Make History

Lead team members of the project are Ilana Bonder and Hadar Ben-Tzur. In the mobile application of Let’s Make History, a user can travel back in time to Washington Square Park through augmented reality. Users can also join Wallace and June- two young activists on a 1968 spring day, in a cinematic experience.

NYCML hosted an interesting discussion on the future of synthetic media. For some, computer-generated images, videos, text and voices can be a source of entertainment and yet, the potential for danger is extraordinary. This debate was set to address the proposition, “synthetic media will do more good than harm,”. Ken Perlin, a professor in the Department of Computer Science at New York University and Eli Pariser, an Omidyar Fellow at New America Foundation were for the proposition, arguing that synthetic media will do more good than harm. Ambassador Karen Kornbluh, Senior Fellow for Digital Policy at the Council on Foreign Relations and serves as a Governor on the U.S. Broadcasting Board of Governors and Matt Hartman, a partner at betaworks ventures were against the proposition, arguing that synthetic media will do more harm than good.

Both teams started with the definition of synthetic media. Eli Pariser explained that how simple images and videos can deceit humans by showing the audience some examples. He made a point that every source of technology can be used to harm people. His team member, Ken Pariser added to his argument, explained how synthetic media changes with time and it has been there for some time. According to him, at some point radio was a medium of manipulation. The highlight of Ken Pariser’s argument was that we need to trust the goodwill of humans. He explained entertainment usage of synthetic media.

Karen Kornbluh shared her personal experience as a policymaker and explained that how technology has been challenging democracy. Policies have been made to counter those challenges and to ensure a people’s right to information. Part of her argument was that people are evil and they are going to use synthetic media for their benefits. Her argument was very similar to one in the paper Digital Life in 2025″ Abuses and abusers will ‘evolve and scale.’ Human nature isn’t changing; there’s laziness, bullying, stalking, stupidity, pornography, dirty tricks, crime, and those who practice them have new capacity to make life miserable for others.” She further added that we need to understand the harm so that we can make policies accordingly. Matt Hartman claimed that most of the examples of synthetic media are harmful. He acknowledged the entertainment aspects of synthetic media. Referring to the current situation in USA’s Politics he added that we are witnessing the threat posed to our democracy by synthetic media.

This debate was moderated by Manoush Zomorodi, co-founder of Stable Genius Productions. Both teams presented solid arguments. In the end, I agreed with Karen Kornbluh and Matt Hartman that synthetic media has the potential to do more harm and it is important that we create policies accordingly.

Demo Expo

At the expo, students displayed emerging media and technology prototypes. It was an amazing experience for me. The astounding ideas presented by the students were motivational for me. It will be interesting to see how augmented and virtual reality are going to impact the world.

Summit’s like NYCML’18 can bring people from the tech industry and academia together, to work towards a better future for humanity in this advanced technological world.

Cited Work

Anderson and University’s – NUMBERS, FACTS AND TRENDS SHAPING THE WORLD.Pdf. https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/831785/mod_resource/content/0/PIP_Report_Future_of_the_Internet_Predictions_031114.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec. 2018.

Anderson, Janna, and Elon University’s. NUMBERS, FACTS AND TRENDS SHAPING THE WORLD. p. 61.

Larry Diamond. “Liberation Technology.” Journal of Democracy, vol. 21, no. 3, 2010, pp. 69–83. Crossref, doi:10.1353/jod.0.0190.

Larry Diamond – 2010 – Liberation Technology.Pdf. https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/831842/mod_resource/content/1/21.3.diamond.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec. 2018.

Press, The MIT. “The Invisible Computer.” The MIT Press, https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/invisible-computer. Accessed 10 Dec. 2018.

Sayers, Jentery. Technology | Keywords for American Cultural Studies. https://keywords.nyupress.org/american-cultural-studies/essay/technology/. Accessed 10 Dec. 2018.

Helpful Links

https://nycmedialab.org/

https://nycmedialab.org/prototyping-projects/

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEV0ObzNb_nFzrGS841niIA

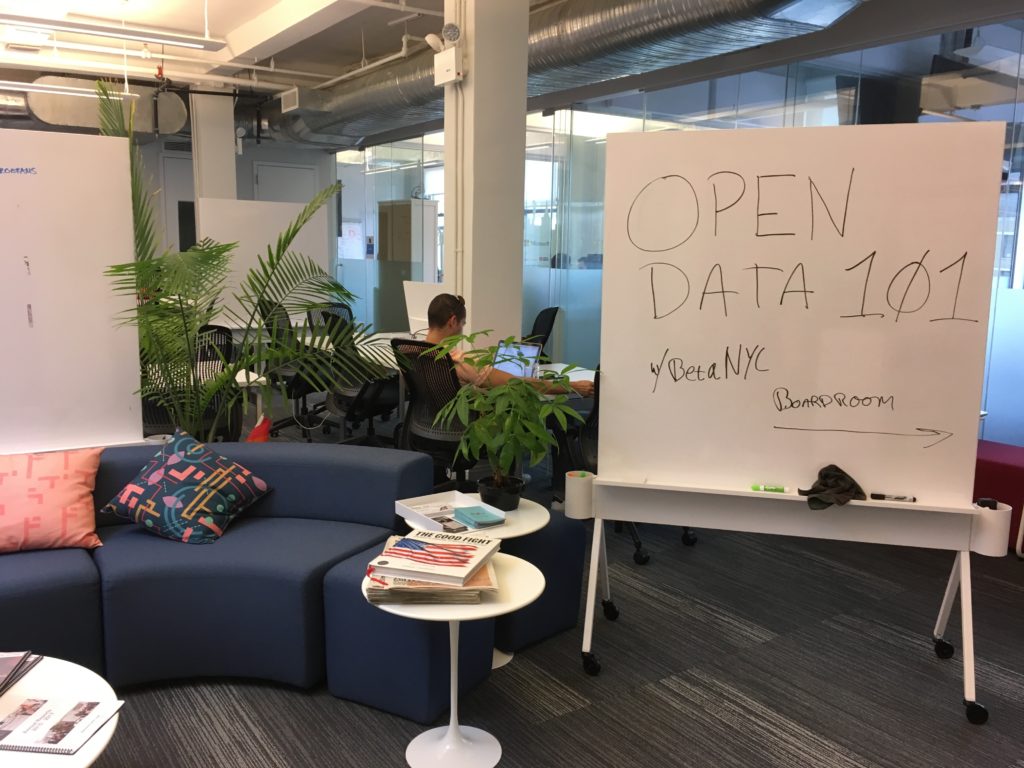

I found this governmental class on

I found this governmental class on

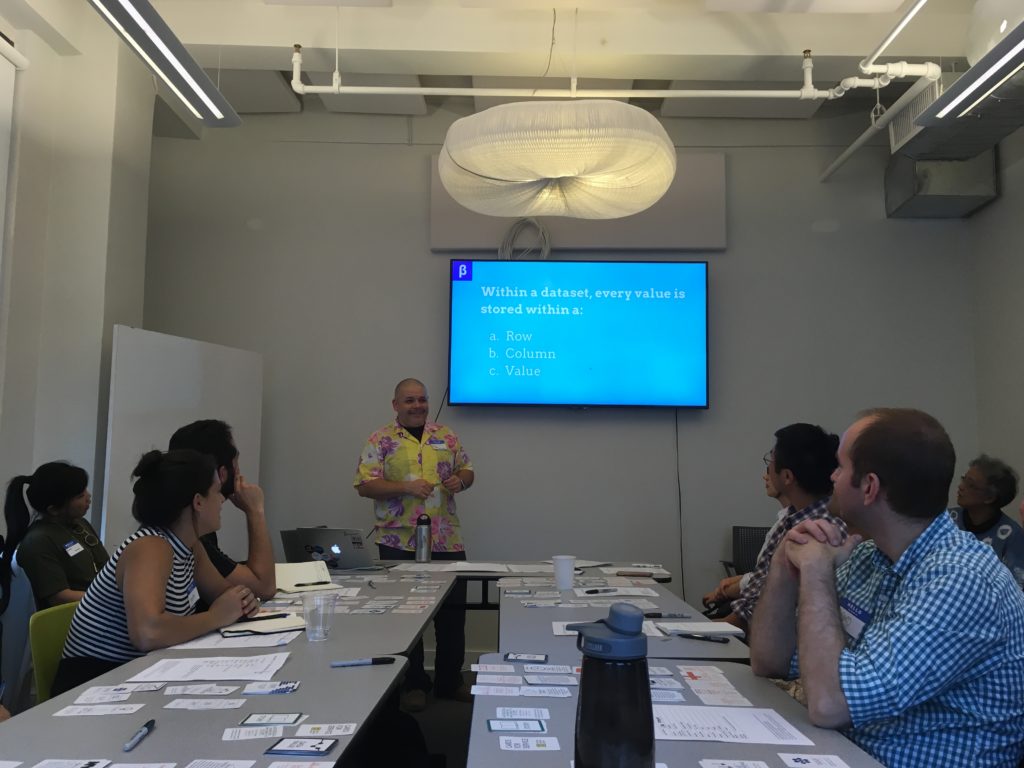

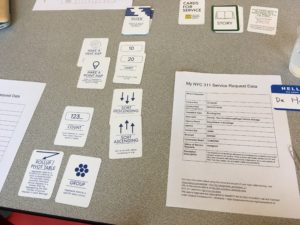

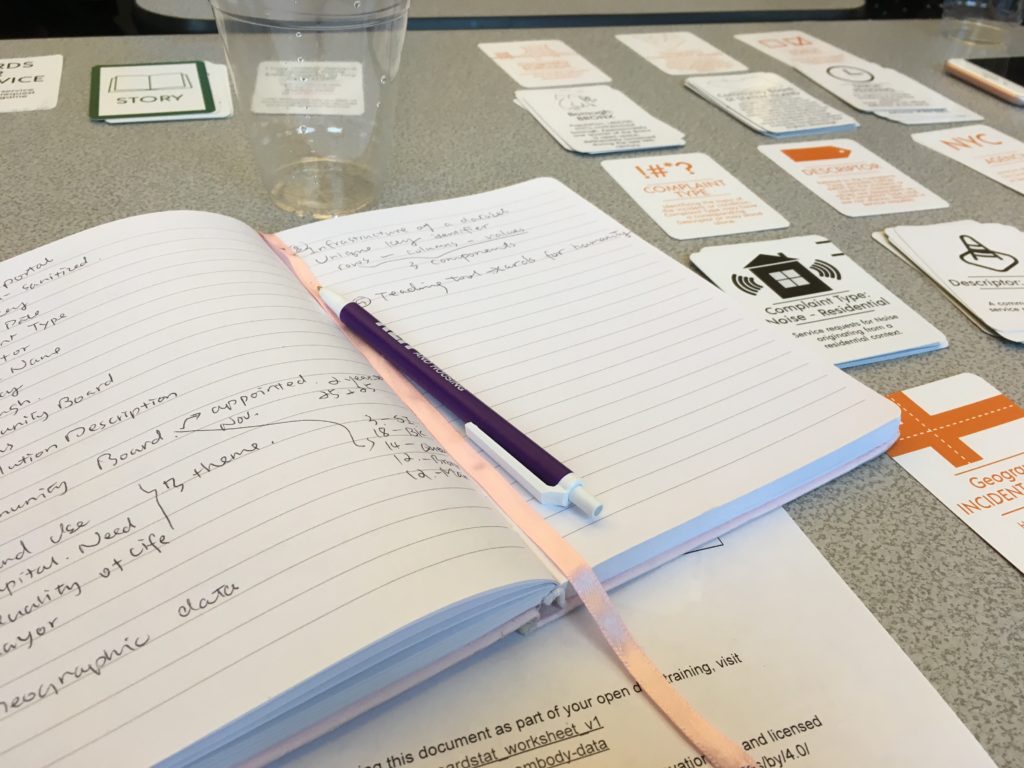

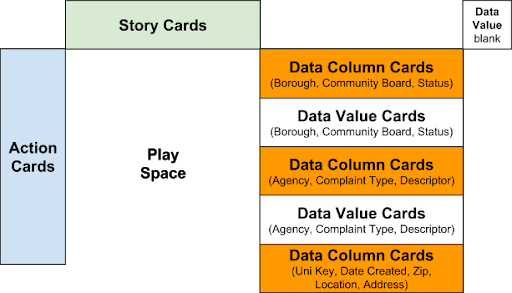

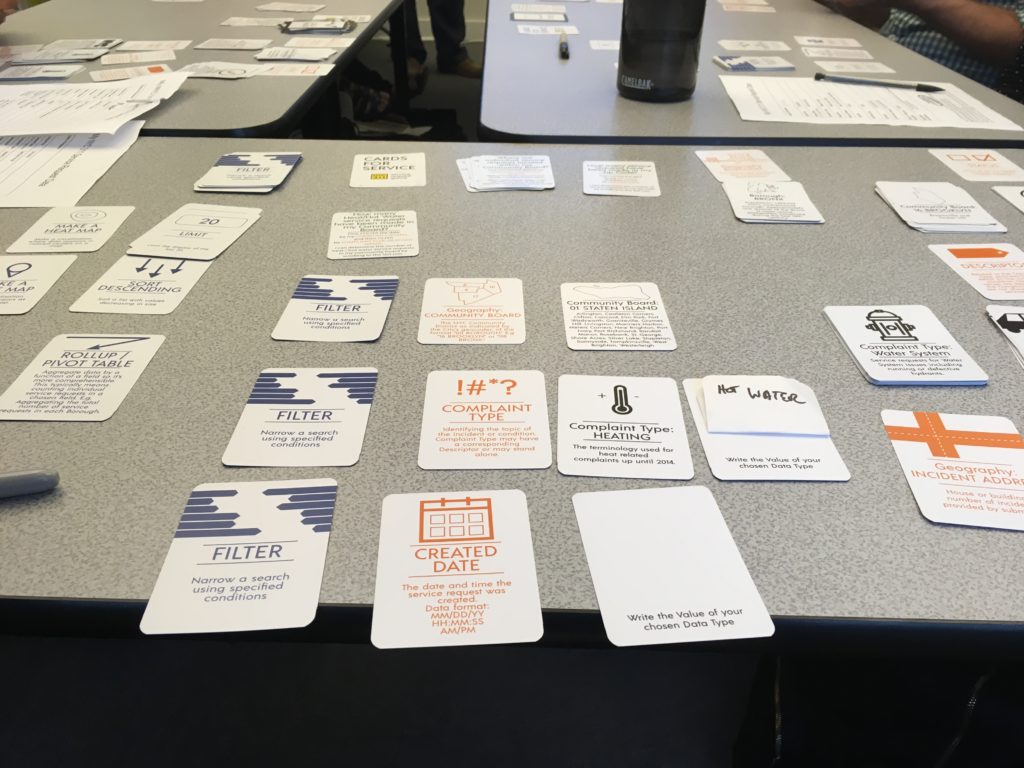

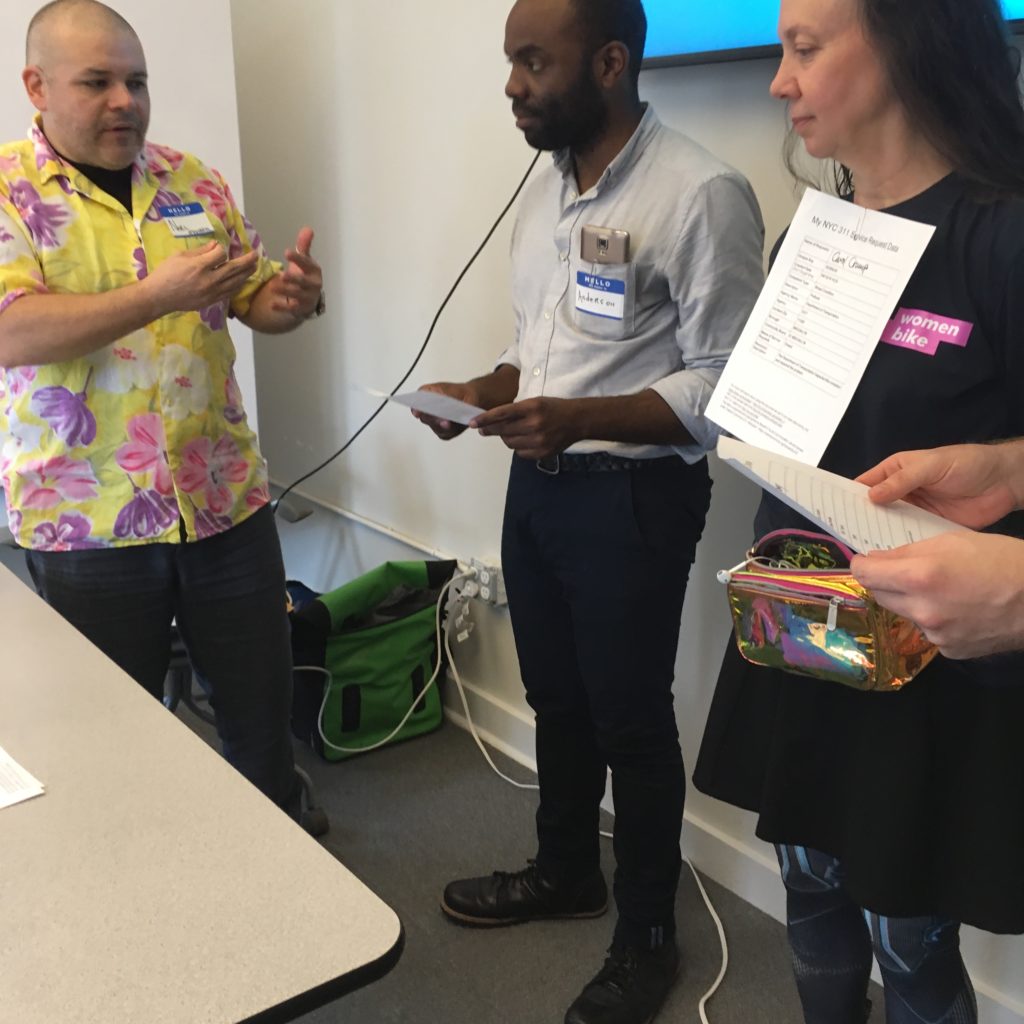

After the icebreaker exercise, everyone get to know each other better and feel closer, as we have been in the same data set and under one task. Each of us act as datum and we served together for a common purpose. We moved to the next activity : Playing with cards!

After the icebreaker exercise, everyone get to know each other better and feel closer, as we have been in the same data set and under one task. Each of us act as datum and we served together for a common purpose. We moved to the next activity : Playing with cards!

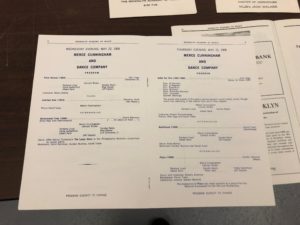

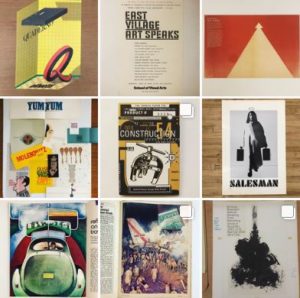

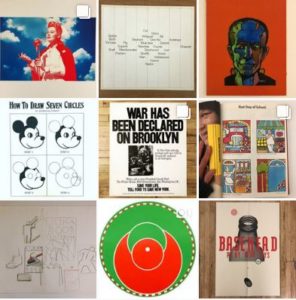

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at  phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,

phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,  archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display.

archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display. which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.

which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.