Place: Spyscape Museum

This summer, I visited the Spyscape Museum in Manhattan. It’s at once a museum and an activity: while it has exhibits about counterintelligence operations, cryptography, and other “spy”-related topics from across history, it also comes with a significant interactive component, leading visitors through quizzes and games.

The whole museum is centered around a challenge of sorts, geared towards discovering what sorts of skills you have that could be relevant to various professions related to spying, including field operators, handlers, researchers, and codebreakers, among other roles.

Beyond being a fun way to spend a few hours away from the summer heat, the Spyscape Museum actually made me curious about many of the things I learned there, such as the Anonymous movement, cryptography’s legacy in the digital age, and the role of covert operators across history.

As a museum, Spyscape is an institute of information, cataloguing and preserving different histories of covert operations. Spyscape, like many museums, teaches by a method called interpretation.

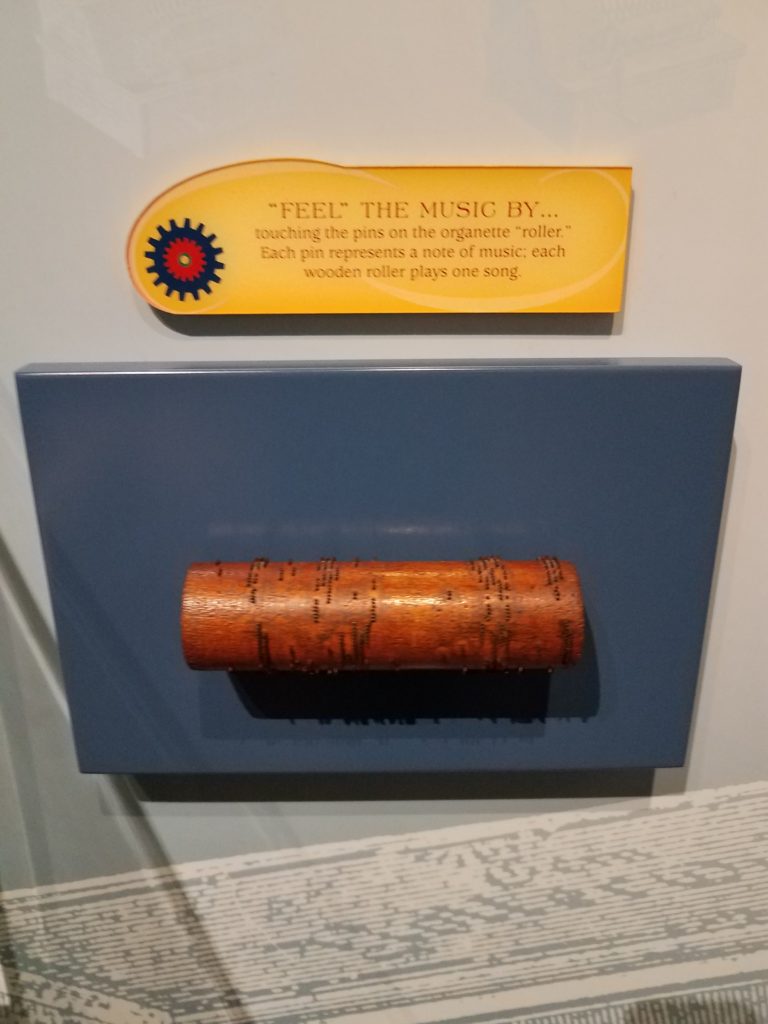

“Interpretation relies heavily on sensory perception—sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and the kinetic muscle sense—to enable the museum-goer emotionally to experience objects.”

(Alexander, 2008)

With visual and audio components to its exhibits, plus touch screens that allow visitors to play games and answer questions, Spyscape certainly makes use of the full sensory experience.

The subjects of the museum, cryptography and covert operations, also deal heavily in information: protecting it, freeing it, and controlling who has access to it.

“Nations go to great lengths to gain [information] by using the time-honored tools of espionage and codebreaking to gather information secretly. … Codebreaking evolved from the ancient art of pencil-and-paper puzzle solving to the science of cryptanalysis.”

(Gannon, 2001)

This evolution in cryptography mirrors the journey of the information field, from the simplest of roots to the complex webs of information we have today in the digital age. It’s this evolution that the Spyscape Museum catalogues, interprets, and shares for its visitors.

Person: Alan Turing

One of the most important people in the history of cryptography, whose story was given great focus in one of Spyscape’s exhibits, was Alan Turing. He’s famous for leading the World War II-era British counterintelligence team that beat the German Enigma machine, which encrypted messages according to regularly-changing ciphers that were difficult to crack. But he had a hand in many other information-related operations during and after World War II, and his life itself is a study in how information can have an impact on a personal level.

Turing’s claim to fame was his work for British counterintelligence on the Enigma problem.

“The science of numbers and symbols was in Turing’s genes … [He] ignored the intimidating numbers and put his trust in what he knew—mathematical logic.”

(Gannon, 2001)

Having an eccentric manner but an undeniably genius brain, he gained respect from his colleagues and managed to find a solution that reliably broke the codes created by Enigma machines.

Even after the war, Turing continued to work in information-related fields, going on to lay “the foundations for computer technology and artificial intelligence” (Spencer, 2009). His work, in large part, has been the starting point from which much of the digital age has sprung: computers, machine learning, and data analysis, in their modern iterations, have all been influenced by Turing’s work.

Of course, the sensitivity of Turing’s projects during World War II meant that he wasn’t publicly recognized for his contributions to ending the war; he had to keep his work a secret from even his family.

“Turing’s oldest niece, Inagh Payne … recalls sitting on his knee asking him repeatedly what he did at the office. Turing remained quiet about his work for the war effort.”

(Spencer, 2009)

And this wasn’t the only part of his life he had to keep a secret: his homosexuality, for which he was eventually criminally prosecuted, was another large piece of information about him that could not see the light of day.

It is this juxtaposition between his work and his life that strikes me most about Alan Turing. His life’s work, the achievement for which he is most recognized, is that of freeing information, revealing secrets, and saving lives by being able to break codes and open lines of communication. But in his personal life, neither recognition for his incredible deeds in the service of his country, nor the simple liberty of being able to love freely, were granted to him. Exposing and withholding information are two sides of the same coin; perhaps no one knew that coin as well as Alan Turing.

Thing: Cryptex

While I was at the Spyscape Museum, I couldn’t help but reflect back on one of the first books that ignited my interest in cryptography: The Da Vinci Code. Though I haven’t read it in a long time, a few of the concepts from the book have really stuck with me. One of the things that has always intrigued me is an object called a cryptex.

“A portable container that could safeguard letters, maps, diagrams, anything at all. Once information was sealed inside the cryptex, only the individual with the proper password could access it.”

(Brown, 2003)

This device struck me as a genius invention when I first encountered it — appropriately, it was credited to Leonardo Da Vinci in the story. For a while, I believed that was its origin, but actually, it was invented by Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code’s author.

The cryptex itself is obviously linked with information: namely, it’s designed to protect information from everyone but its intended recipient. But the real-life story of this fictional object also has a lot to do with the way we interact with information, especially when it can be used for profit.

A year after the publication of The Da Vinci Code in 2003, a fan of the book named Justin Nevins created the first physical replica of the cryptex. Shortly thereafter, he trademarked it — which led to a dispute between Nevins and Columbia Pictures when The Da Vinci Code was adapted into a movie. Nevins wrote out his side of the story many years later on a forum website (Nevins, 2017).

As Nevins tells it, Dan Brown didn’t have a problem with him holding the trademark for the cryptex at first. But when The Da Vinci Code‘s movie was in production, Columbia Pictures wanted to make their own replicas for the movie, and wanted Nevins to drop the trademark. Nevins and Columbia Pictures eventually settled out of court: the movie was allowed to use the word “cryptex,” but Nevins was allowed to keep his trademark. He still sells cryptices online.

This part of the story is, understandably, not as well known as the cryptex itself; but it brings this device from a fictional object to a technology of the real world. Copyrights and trademarks are a big part of regulating how information can be used and received in the world, which echoes the original purpose of the cryptex itself: keeping information from certain parties, and revealing it to others.

The cryptex’s journey from fiction to reality illustrates the importance of information: the creativity that can happen when it’s shared with the world, and the monopolization that might ensue when it’s kept safeguarded in just a few, powerful hands.

References

Alexander, E. P., & Alexander, M. (2008). Museums in Motion: An Introduction to the History and Functions of Museums. Lanham, MD: Rowman et Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Brown, D. (2003). The Da Vinci Code. New York: Doubleday.

Gannon, J. (2001). Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth Century. Washington, D.C.: Brasseys.

Nevins, J. (2017). The history of the Cryptex. Retrieved from https://forum.thecodex.ca/t/the-history-of-the-cryptex-r/70.

Spencer, C. (2009). Profile: Alan Turing. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/8250592.stm.

Spyscape Museum. Retrieved from https://spyscape.com/.