Introduction

The Green-Wood Cemetery is a historic landmark located in Green-Wood Heights in Brooklyn, New York. Founded in 1838 as a non-sectarian Christian burial site, the cemetery stretches a monumental 478 acres and houses over 560,000 permanent residents. Famous New Yorkers buried there include Leonard Bernstein, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and William ‘Boss’ Tweed. It is also home to approximately 3300 Civil War veterans. I paid the cemetery a visit on the morning of November 2. Later that afternoon, I and a few other students from Pratt’s SAA chapter were privileged to a tour of the cemetery grounds by Green-Wood’s historian Jeff Richman and its records and archival collection by archivist Anthony Cucciara.

The cemetery as a site of information

There is no shortage of information one can find at the at Green-Wood. It prides itself in being not just a cemetery but also a park, an arboretum, a sculpture garden, and a cultural institution where visitors can learn about New York’s history. The cemetery hosts variously themed historical tours, as well as exhibits, lectures, and symposiums on topics revolving around death and the macabre.

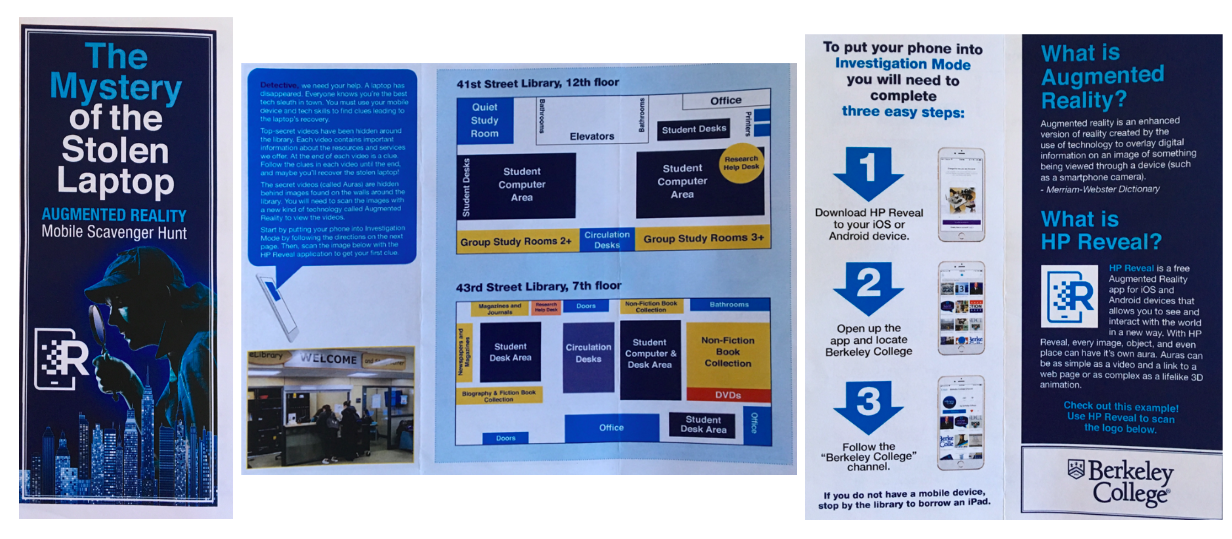

No institution can survive in the present age without embracing digital technology. Green-Wood goes above and beyond in taking advantage of technology to provide information. An example of this is their meticulous documentation of the various wildlife found on its grounds. Over 8000 trees and shrubs decorate the cemetery, with new species being acquired and planted (under the supervision of Director of Horticulture Joseph Charap) to this day. In addition to having placards attached to each tree identifying their respective species, an app was launched in 2011 that includes a digital inventory and map of every tree planted in the cemetery.

Another example of the cemetery’s use of digital technology is its grave search system. If one wishes to locate a specific person buried at the cemetery, one can simply look them up on Green-Wood’s website and be provided with their burial date as well as lot, section, and grave numbers. One can then locate the lot number to its address using Green-Wood’s comprehensive map. Interactive kiosks can also be used at the visitor center as well as the mausoleums on site to locate a person’s burial place.

On the tour, resident historian Jeff Richman regaled us with stories concerning the cemetery’s illustrious residents, including Rose Guarino—who was rumored to be assassinated by a mafia family but was in reality shot to death along with a servant girl (Annie Tarello) by a male caretaker (Pietro Silverio).

The cemetery as an archive

After a tour of the cemetery grounds, archivist Anthony Cucciara took us to the administrative offices to give us a look at the cemetery’s archives. Green-Wood’s collection of artifacts consists of artwork made by its residents, photographs, personal belongings and correspondences, as well as published books. The collection is in the process of being digitized and can be browsed online here.

Green-Wood’s records include genealogical charts, family trees, last wills and testaments, death certificates, burial orders, lot records, family correspondence, and affidavit records, as well as architectural blueprints and records of the various day-to-day operations of the cemetery. Volunteers and interns can be found at work preserving and re-housing those documents. A database for these records with finding aids can be found here.

Reflections

The Green-Wood Cemetery proves itself to be a valuable institution not just because of its basic utility as a burial place but also as a historical and cultural site with educative capabilities. Its archive paints a beautiful and rich picture of the unique history of New York. But as Rilke reminds us in his Duino Elegies, underneath beauty is always terror. Green-Wood exemplifies this not just in the obvious way (it’s a cemetery) but also in the way it belies a sharp class dynamic that was present at the time of its founding (and, we should add, no less present now). In Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory, Schwartz and Cook write, “…archives are established by the powerful to protect or enhance their position in society. Through archives, the past is controlled. Certain stories are privileged and others marginalized.” The largest and most ornate monuments in the cemetery tend to be the subjects of tours, but they also tend to belong exclusively to wealthy families. Thus, the stories of the poor and working class, who often cannot afford a proper burial let alone a monument, are not often told to the public.

At the same time, the cemetery also has the power to recover the previously lost stories of the disenfranchised. An example of this is the mass grave and memorial for 103 people who died in the Brooklyn Theater Fire of 1878. The bodies buried there belonged to those who could not be identified or whose families could not afford a proper grave. But in a blog post entitled Putting a Face on a Tragedy , Jeff Richman was able to put a name and face to one of the buried through historical investigation—Donny Rose.

Preservers of memory are not predestined to always mimic power. They can serve as resistance to power precisely by making its presence known and relating the stories of its victims.

Thank you @GreenWoodHF, Professor Cucchiara, and the students of @PrattInfoSchool who came out today for an AMAZING tour of the grounds and archives at Green-Wood Cemetery!! ?⚰️?? #GreenWoodCemetery #brooklyn #SLA #SAA #archives pic.twitter.com/N91cqcvlVg

— Pratt SLA (@prattsla) November 2, 2018

Notebook wallpaper from Martos Gallery exhibit

Notebook wallpaper from Martos Gallery exhibit