Introduction

A field study observing the digital interaction of young users was conducted on a second-generation, three-year-old boy of Afro-Indo Caribbean descent. The observation was conducted in the observer’s home.

The purpose of the study was to better understand the intuitive use of young children. How do they know to navigate and interact with features as they do? How do they learn these behaviors in unsupervised environments? How are their behaviors reinforced and applied across devices?

Many of these questions were a result of the above curiosities and a desire to better understand the cognitive processes at play as noted by Kuhlthau:

“A model representing the user’s sense-making process of information seeking ought to incorporate three realms of activity: physical, actual actions taken; affective, feelings experienced; and cognitive, thoughts concerning both process and content. A person moves from the initial state of information need to the goal state of resolution by a series of choices made through a complex interplay within these three realms (MacMullin & Taylor, 1984). The criteria for making these choices are influenced as much by environmental constraints, such as prior experience, knowledge, and interest, information available, requirements of the problem, and time allotted for resolution, as by the relevancy of the content of the information retrieved” (p. 362).

The structure of this field report was a combination of interview and observation. The purpose structure was due primarily to the subject’s age.

Disclosure

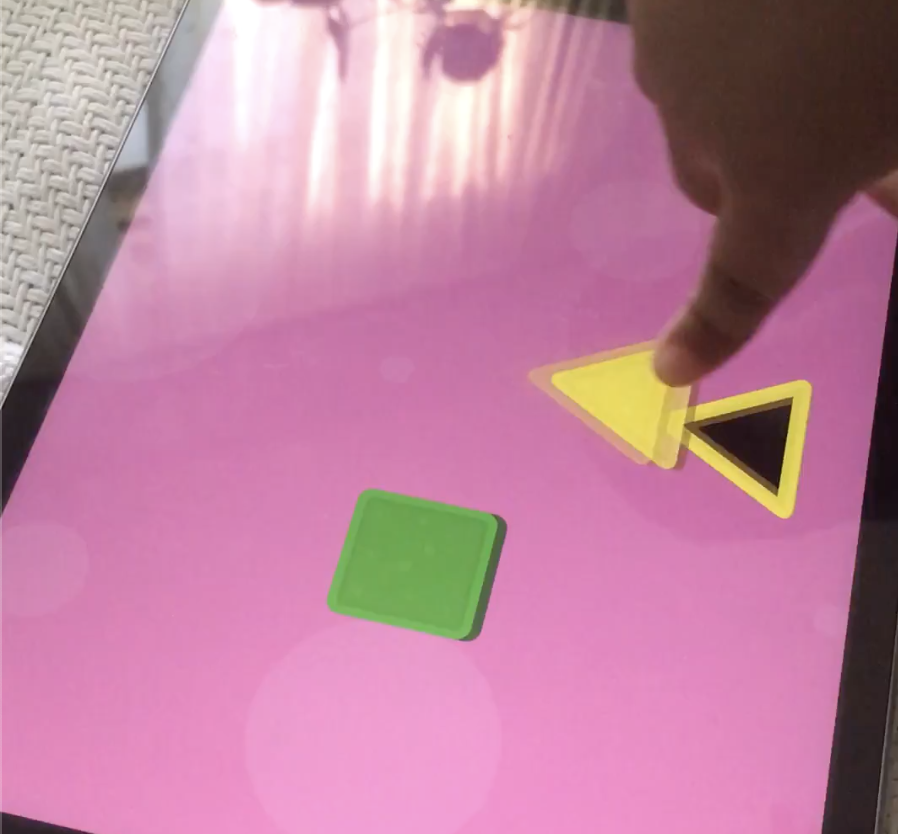

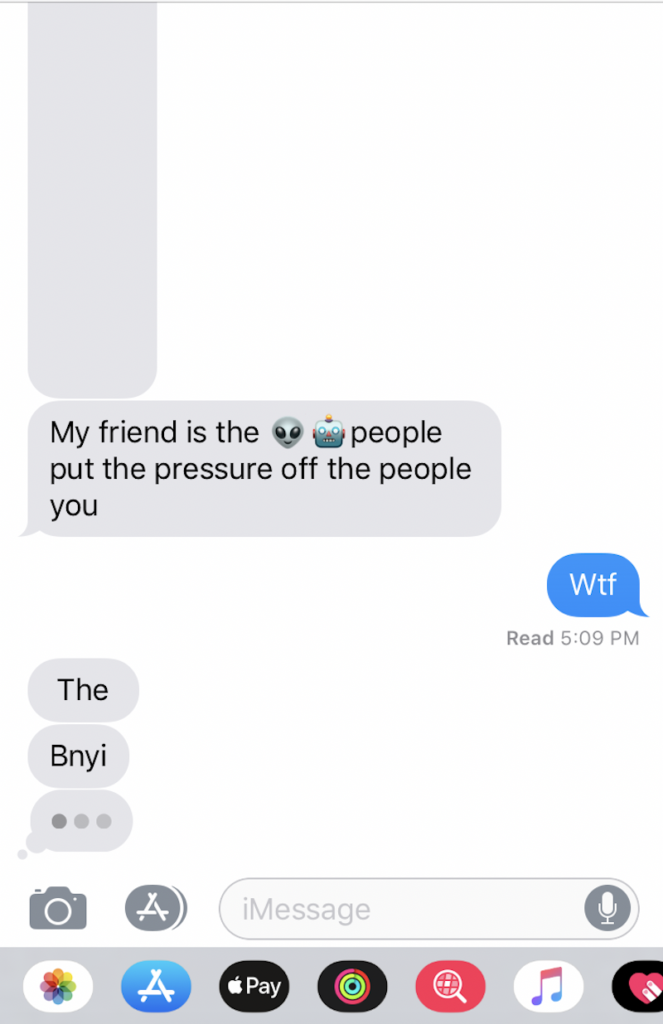

The subject of the observation is the observer’s nephew. Alluded to below, one of the many reasons why this observation was informally conducted was due to general curiosity. This initial curiosity began when noticing the subject’s use of mobile devices but, most recently, when he began sending nonsensical messages. The messages were initially thought to have been a prank by the subject’s mother but upon further inquiry, and frequent occurrences, the messages were a combination of drawn shapes or autocompleted phrases that were illogically constructed.

Observations within the scope of this study included 1) how interaction changed or remained the same across an iPhone and iPad 2) interaction with specific features and implicit restrictions imposed on the user (e.g., inability to read or write).

“Motivation for doing the work”

According to “The Ethics of Fieldwork” by PERCS: The Program for Ethnographic Research and Community Studies – Elon University, listing motivations for conducting such studies better align the researcher with the outcome of the intended study and the benefits to the research field as a whole.

For many reasons, this study was not formally conducted. However, there are two reasons worth noting within the scope of this report. The first reason is due to the little experience the observer possessed in field studies containing child subjects. Leveraging practices from the readings within the study resulted in applying generalized techniques and procedures intended for adult subjects to a child subject.

Outlined later in greater detail, this posed many issues as one would expect the application of techniques and procedures reapplied in very different circumstances. However, motivation for pursuing this study prompted an attempt and a review of not only this study but also the review of unique requirements for child subjects. Hence, the second reason why the observation was not formally conducted: to better understand at what scale technology impacts early childhood development.

Possible Harms: skewed results due to the misuse of techniques and procedures.

Possible Benefits: generated interest to pursue, rectify, and advance this study.

Techniques

General tasks were assigned:

- Interact with a mobile feature

- Find and watch your favorite YouTube video

- Play an educational game

- Play a non-educational game

As the subject worked through each task, some intervention and rewarding were required. Having known the subject, the tasks created were short in length–sufficient enough for possible naps or breaks–and the entire observation spanned across several hours. Snacks were rewarded for good behavior and for completing a task without interruption.

After completing the above tasks, the subject was closely observed to document any behavior which didn’t occur while completing those tasks.

Questions and notes from the observation

- Activity Theory: in-practice

- How would his actions change if the technology changed as Nardi claims, “Activity theory holds that the constituents of activity are not fixed but can dynamically change as conditions change” (p.38)?

- Attention span: what does his actions say about the effect of technology on youth users’ ability to focus?

- Never completes viewing of videos and tends to navigate to either the search bar or another video within 30 seconds to 2 minutes of viewing.

- Viewing videos of greater interest last longer than 2 minutes but are never fully completed.

- When a task was issued, the subject wanted to continue on longer for all tasks but the educational game. For the educational game, the user became frustrated unless there was sufficient guided intervention.

- Voyeurism and the gaming culture: the subject’s attention was only kept when watching YouTube videos of others playing videos games or playing with toys.

- Distributed Cognition (Nardi, p. 38): pattern recognition?

- Participant cannot read nor sufficiently write. However, he is able to search YouTube videos he’s previously watched but is unable to search newly watched videos. To return to new videos, he taps the arrow icon to return to the video.

- How he searches is by typing in the first few letters he remembers from the videos he’s views frequently. For retained previous search results, he reviews the list and selects which is most recognizable. He watches and then returns to the search bar if the video isn’t what he wanted. If the video is what he was looking for, he scrolls to the recommended videos to find new content and selects those items or searches content from the same channel of the video he’s currently viewing.

- Signifiers and affordances

- Participant understood the significance of the hamburger menu, toggles, touchscreen interface features such as swiping, device volume control and locking mechanisms, and other navigational signifiers such as the back/forward and up/down arrows.

- Interaction

- iPhone and iPad

- YouTube and either a mobile app/feature.

- No major differences in interaction other than the subject’s level of comfort and which device he preferred to use when.

- The iPhone was generally used when sitting up.

- The iPad was generally used when laid back.

- iPhone and iPad

- Intervention

- The study would be better conducted in a more controlled environment/location, without the mother nearby and by an individual with a balanced relationship.

- Observer’s relationship with the subject was unbalanced. This required swapping between the mother as an instructor to guide him through exercises.

- With the mother, the subject was at ease and felt less intimidated by the instructions and how they needed to be carried out.

- The subject preferred guided instructions as opposed to unguided instructions. While guided instructions were more successful with the observer, they weren’t as successful as with the mother.

- The subject enjoyed general instructions with sufficient freedom to navigate and course-correct by intuition than delegated navigational instructions.

Conclusion

The above study would do well with well-controlled environment, an unrelated observer with sufficient trust, and a well-vetted plan of tasks.

Additionally, prior to an observation containing child subjects, it would be helpful to know positive and negative triggers, learn what they like and what they dislike, review popular content for that age group and test the level of interest on the subjects, provide ideal rewards for completed tasks, and create a balance reward system.

Overall, this observation did provide an opportunity to analyze the subject’s behavior more closely and to develop a thoughtful hypothesis. Nardi explains that “activity theory recognizes that changing conditions can realign the constituents of an activity” (p. 38).

My original assumption that technology results in specific behaviors in young users has shifted to a hypothesis which accounts for the bidirectional relationship between any user and technology: technology reinforces or redistributes behaviors in young users which may predict their usage of other technologies and platforms, and related social behaviors.

References:

Kuhlthau, Carol C. “Inside the Search Process: Information Seeking from the User’s Perspective”, “Journal of the American Society for Information Science 42(5): 361–371. https://ils.unc.edu/courses/2014_fall/inls151_003/Readings/Kuhlthau_Inside_Search_Process_1991.pdf

McGrath Joseph E. “Methodology matters: doing research in the behavioral and social sciences”. https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/876402/mod_resource/content/0/mcgrath-methodology%20matters.pdf

Nardi, Bonnie A. “Studying Context: A Comparison of Activity Theory, Situated Action Models, and Distributed Cognition”. https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/876415/mod_resource/content/1/nardi-ch4.pdf

PERCS: The Program for Ethnographic Research & Community Studies, “The ethics of fieldwork”. Elon University. http://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/org/ percs/EthicsModuleforWeb.pdf

Wilson, T. D. (2000). “Human information behavior.” Informing Science 3(2): 49–56. https://www.ischool.utexas.edu/~i385e/readings/Wilson.pdf