In September, CUNY Graduate College hosted a livestream event featuring a lecture from Lorena Gauthereau, CLIR-Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at Recovering the US Hispanic Literary Heritage (Recovery) at the University of Houston, that focused on colonialism’s influence on digital humanities and archives – particularly when analyzing Latinx digital humanities in the US – and ways that this influence can be deconstructed through the use of digital tools and methods. The event was held at the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH) as part of their Digital Dialogues series.

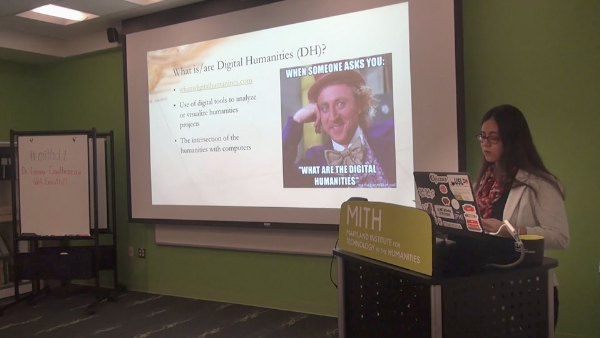

Throughout her lecture, Gauthereau observed that “archives have historically functioned as a tool of colonialism” and outlined the ubiquity of colonialist practices in archival institutions. In her work at Recovery, she finds that digital technology can be a way to restructure the framework in which archives have traditionally operated to give archival and custodial control back to the people whose lived experiences are supposed to be represented in an archive. While she says the definition of “digital humanities” varies (she suggests checking out What is Digital Humanities?, a humorous site that yields a different definition every time the page is refreshed), “the use of digital tools to analyze or visualize humanities projects” or “the intersection of the humanities with computers” could both be sufficient.

Through the use of decolonial and postcolonial theories, Gauthereau says that we must always approach “the digital with a critical eye” in order to restructure the frameworks of digital humanities to center the lived experiences of people who are not being represented or are being misrepresented. While decolonial methods are “approaches to coloniality (the underlying colonial structures that continue to exist even today) that try to de-link from colonial epistemologies and ontologies,” postcolonial methods “look at the big picture” of colonialism and the impact it still has today. Put another way, she says, decolonial theory stems from postcolonial theory, where postcolonial theory operates on a macro-level approach to the structures of colonialism, and decolonial theory operates on a micro level.

For any information professional, constantly considering the cultural legacy of colonialism is extremely important in our work. In order to avoid appropriation, erasure, or misrepresentation, we must be sensitive to the cultural differences and lived experiences of people whose communities have been exploited by colonialism.

As Amanda Stevens writes in A Different Way of Knowing: Tools and Strategies for Managing Indigenous Knowledge, information professionals can and should make sure that managing indigenous knowledge is useful for the community itself by serving as a resource and involving people from that community in the managing process:

Although projects to preserve indigenous knowledge must be driven by indigenous communities and serve an immediate benefit to the communities, libraries and information professionals can play an important role in assisting with the management of indigenous knowledge. In partnership with these communities, institutions such as libraries, museums and universities, can provide valuable resources and expertise for collection, organization, storage and retrieval of information. In fact, some institutions are already in possession of indigenous materials that they are repatriating or trying to make accessible to indigenous communities and others are working in cooperation with indigenous communities to establish collections (Stevens, 2008, p. 27-28).

Stevens also notes that there is no one way to help manage indigenous knowledge, as specific needs and acceptable methods vary across communities (Stevens, 2008, p. 28).

This can be applied to digital archival projects as well. Gauthereau gave examples of a few projects that show how digital platforms can be used to give power back to people and serve as places of reclamation.

“Decolonial digital projects do tell stories of pain,” she says, “but above all, they can tell stories of community, celebration, and survival.”

When discussing Latinx digital humanities online, Gauthereau encourages people to use the hashtag #USLDH.

Works cited:

- Stevens, A. (2008). A Different Way of Knowing: Tools and Strategies for Managing Indigenous Knowledge. Halifax, Canada: School of Information Management, Dalhousie University.