Introduction

Religion has played a prominent role in New Orleans life and culture since its French and Spanish colonial beginnings. Today, the city is home to a wide array of religious denominations including Catholicism, Judaism, and various forms of Protestantism. Each of these groups has a rich and interesting history. These histories, in turn, are interwoven with each other across the spaces and places of the city. One way to understand this complex tapestry is to focus on a particular moment in time. Fortunately, this is possible. During the New Deal Era, the WPA created a directory of the city which contained the names and locations of nearly 800 religious institutions. The WPA archivists working on this project gathered information from a wide range of sources, including official denominational directories, official minutes of conferences and conventions, annuals, journals, pamphlets, city directories, telephone directories, lists of non-taxable property, conveyance records, mortgage records, charters, newspapers, land-use maps, and personal interviews. The information provided in this resource is detailed enough to enable the creation of a large dataset and this dataset is translatable to a fairly detailed Story Map that highlight the religious landscape of New Orleans in 1941. These map, in turn, makes it possible to localize the various denominations present in the city during the Great Depression. Such localizations are valuable for understanding the parts of the city associated with certain groups. This information can help shed light on social, economic, and racial configurations in the city.

Research Question

How might the historical information contained in the WPA Directory of Churches and Religious Institutions in New Orleans provide insights about the scale of religious institutions in the city during the New Deal Era? How might this data be visualized and communicated in a meaningful way?

Literature Review

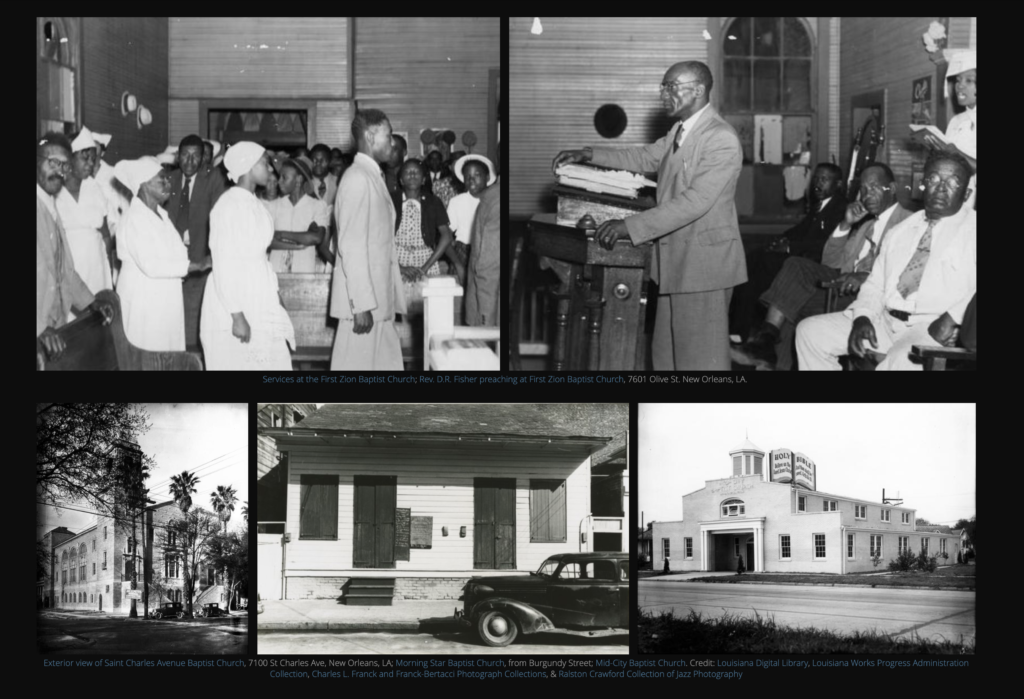

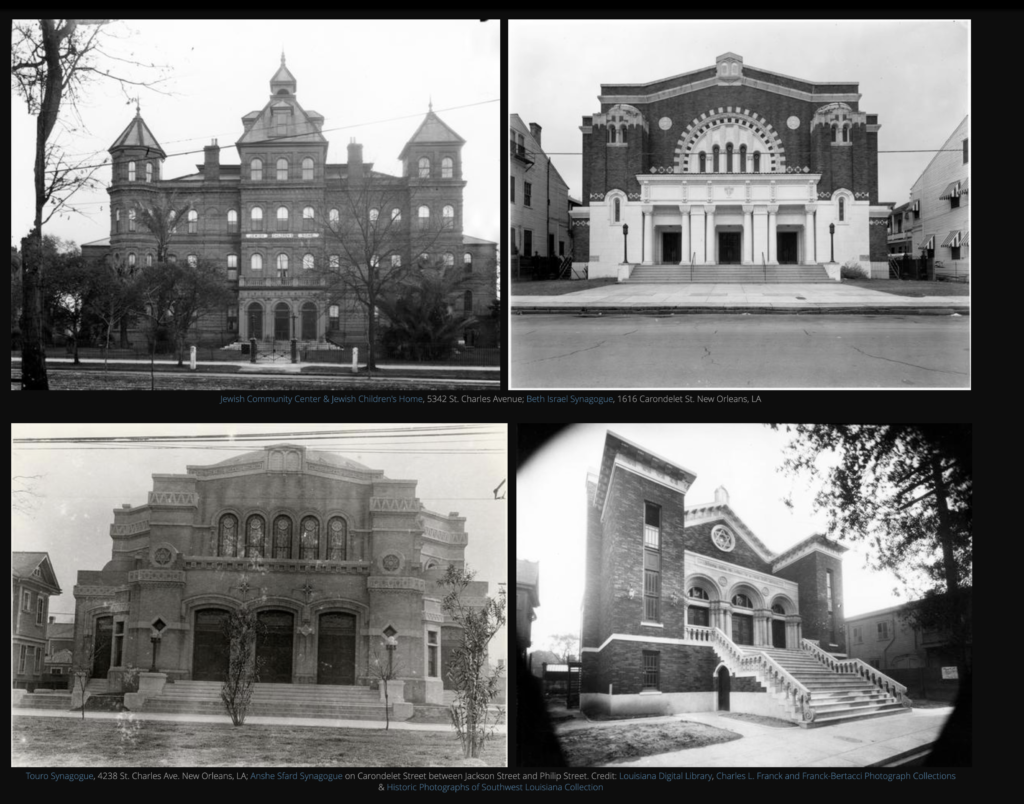

This project presents historical material drawn from primary sources in an interactive, digital format. In turn, exploring literature related to digital history—and how it relates to the digital humanities—provided a helpful lens in creating both the dataset and subsequent ArcGIS Story Map. Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig’s Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web (2005), for instance, provided a framework for development and presentation of historical material on the web. While some of the material in the book was not applicable to this particular project, ideas around design, collection, and presentation proved helpful. Drawing on best practices in visualization, and on scholars such as Edward Tufte, Cohen and Rosenzweig highlight certain aesthetic qualities that those interested in digital history should consider. For instance, layout, color, font, design elements, and multimedia should be given a fair amount of thought before beginning to design on the Web. While working within the confines of the free version of ArcGIS, I was careful to be mindful of web safe colors, clear layout, and easy to understand organization of pictures that included captions and photo credits. Additionally, tried to leverage the Internet to locate materials that could enrich and contextualize the maps created in ArcGIS. These included historic pictures taken by WPA photographers and hosted in the Louisiana Digital Library as well as historical recordings hosted by the Internet Archive’s Audio Collection.

How digital history relates to, and differs from, digital humanities (DH) is not particularly apparent in Cohen and Rosenzweig’s book on doing digital history. Steven Robertson chapter in the 2016 publication of Debates in the Humanities titled “The Differences between Digital Humanities and Digital History”, however, provides an insightful look into the disciplinary relationship between digital humanities and digital history. While DH is often thought of as a ‘tent’ with many disciplines underneath, Robertson posits that it may be more practical to think of DH as a house with many rooms. He conceptualizes these as, “different spaces for disciplines that are not silos but entry points and conduits to central spaces where those from different disciplines working with particular tools and media can gather” (2016). While Robertson notes the overlap between digital humanities and digital history, he also notes two areas of difference. The first area of difference Robertson identifies is focus. Practitioners of the digital humanities are mostly focused on activities that can be classified as “high” academic—presenting at conferences, holding workshops, and creating complex digital tools. Digital Historians, he argues, are more focused on “practical” outcomes and are directed toward creating tools geared for K-12 education as well as public history. According to Robertson, “[w]hat distinguished Digital History from DH is the extent to which historians use the web to distribute and present material to other scholars, place material online to reach and collaborate with the wider public, and to reach teachers and students in classroom settings” (2016). The second area of difference that Robertson identifies is the use of computational tools. Both practitioners of the digital humanities and also digital historians use many of the same tools—network analysis, text analysis, and image analysis. digital historians, however, “have turned to digital mapping to a greater extent than other disciplines in the digital humanities, adopting it as their favored computational tool” (2016). This emphasis on mapping is valuable to digital historians because it allows them to be granular and explore public histories at the neighborhood level.

The collection, cleaning, and analysis of of data as well as the creation of maps is only one portion of telling stories about the past, however. As Cameron Blevins points out in his chapter in Debates in the Digital Humanities (2016) titled “Digital History’s Perpetual Future Tense,” there is more to the practice of history than crunching numbers or building and employing tools. The role of history as a discipline, Blevins notes, is to offer arguments about the past. These arguments, in turn, spark conversation and further analysis. Digital history, however, has largely avoided making arguments about the data it analyses, categorizes, and visualizes. For Blevins, this is approach is understandable given that many digital history projects have occurred under the aegis of public history, which is concerned more with making history accessible and less with the intricacies of academic debate. Rather than appealing to a handful of specialist professors, digital history projects were designed to engage a wide audience who wanted to learn about the past but were not interested in methodological differences or in the historiography of a particular school of thought. Blevins states that the appeal to wider audiences is laudable and that practitioners of digital history need not abandon the mission of accessibility. He argues, though, for making room for argument in these projects. He states, “making arguments is a fundamentally valuable and necessary way to further our collective understanding of the past. History is an interpretive process and argumentation is a means of making that interpretive process explicit” (2016). The act of developing tools and techniques, the mission of making history more accessible, and the work of making and interpreting arguments about the past are not mutually exclusive but are mutually supportive. In my project, I erred most certainly on the side of making the information as accessible as possible. In its current form, the information does not make deep interpretive arguments about the data gleaned from the primary source material. I make note of the colonial past of the region, the hegemonic role of the church in managing and restricting people’s actions, and the ways in which racism shaped, and was shaped by, the religious landscape of the city, but do not engage in finely nuanced debates. In the future direction section, I offer ideas for analysis that would provide even deeper foundations for the kinds of historical argumentation that Blevins advocates.

Methodology

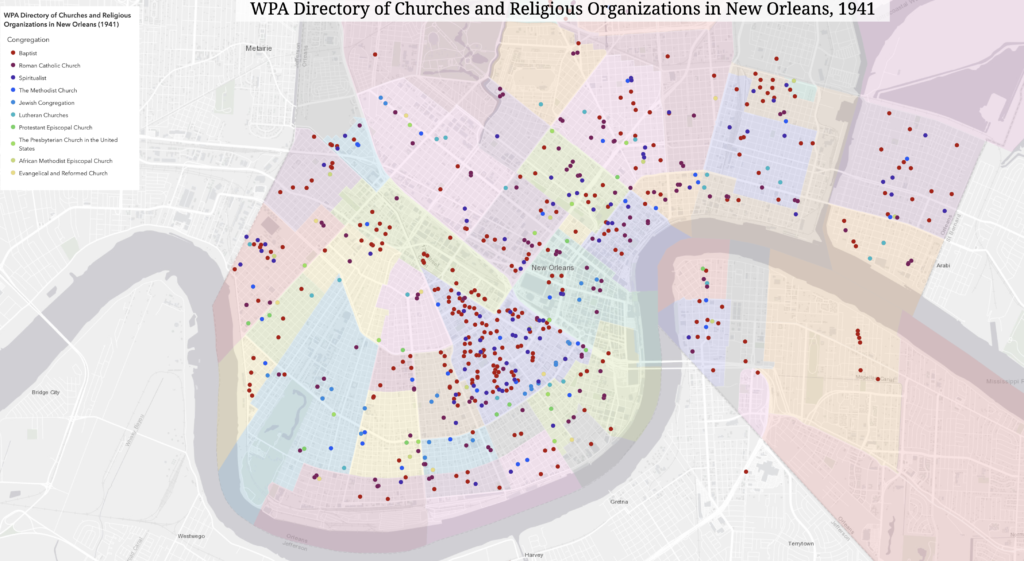

The research methods employed in this project included: historical research and information gathering from primary and secondary sources, data collection from primary sources, data cleaning and analysis, and data visualization. The project began with the primary source document written by the WPA, which provided the information on religious institutions collected by the WPA archivists. This data was compiled into a database, which was cleaned using OpenRefine. The information provided about the institutions included addresses, which made it possible to geolocate the listed sites. The institutions were subdivided by religious affiliation and these subsets were used to narrow the scope of the map analysis. The four groups selected for mapping were Catholic, Baptist, Spiritual, and Jewish. These groups were chosen because they represent the major denominations active (in terms of congregations) in New Orleans during the period under study. The geolocation data for all of these sites was mapped to an ArcGis basemap using neighborhood polygons from the NOLA Open Data Portal. The data points used for this large map were subdivided and color-coded so that each church could be differentiated by religious affiliation. Smaller maps for the four main groups were generated from this data. The map data was then supplemented with period-specific photos drawn primarily from the Louisiana Digital Library, many of which came from the Louisiana Works Progress Administration Collection. Further supplemental materials were added in the form of period-specific audio files sourced from the Internet Archive. Unfortunately, the sound quality of the Jewish cantor files was very poor and, as a result, a much later recording was chosen. Finally, brief descriptive texts were added to the audio-visual information to help orient the site visitor to the WPA in New Orleans as well as the history of the denominations. The information in these segments is drawn from scholarly books and articles, blogs, and podcasts. The website for the project was organized so that there is an brief introduction followed by a map containing the nearly 800 locations from the dataset. Next come sections specifically dedicated to the four main religious affiliations under study. Each of these sections contains text, audio file, photos, and a respective map.

Findings

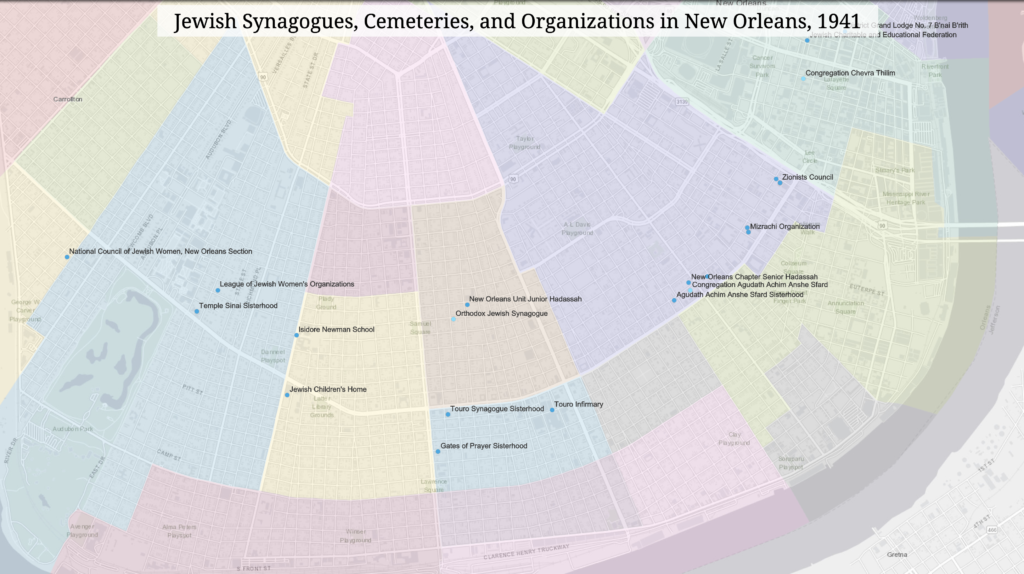

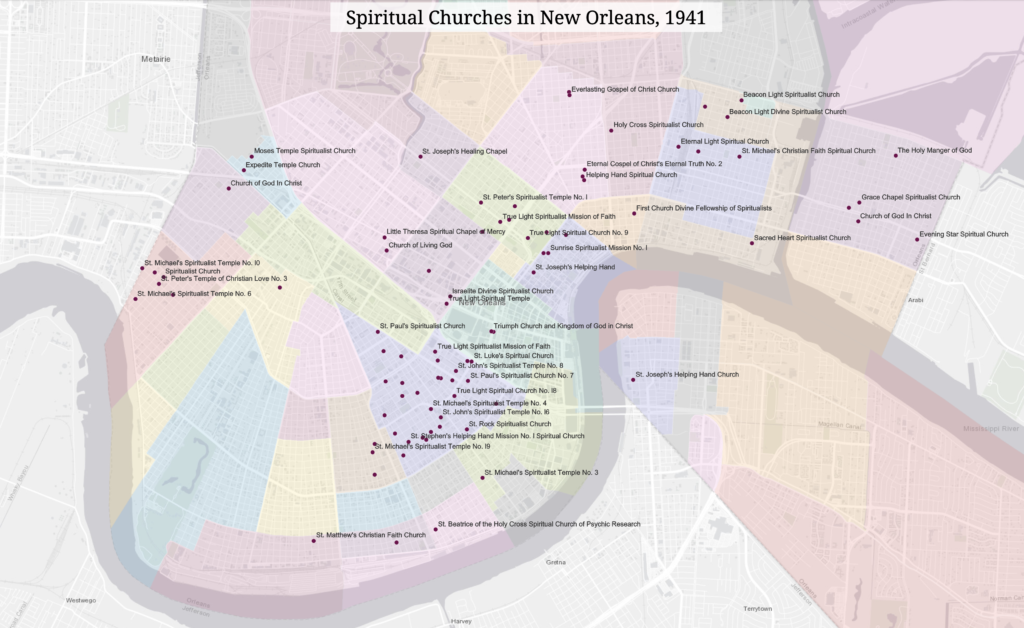

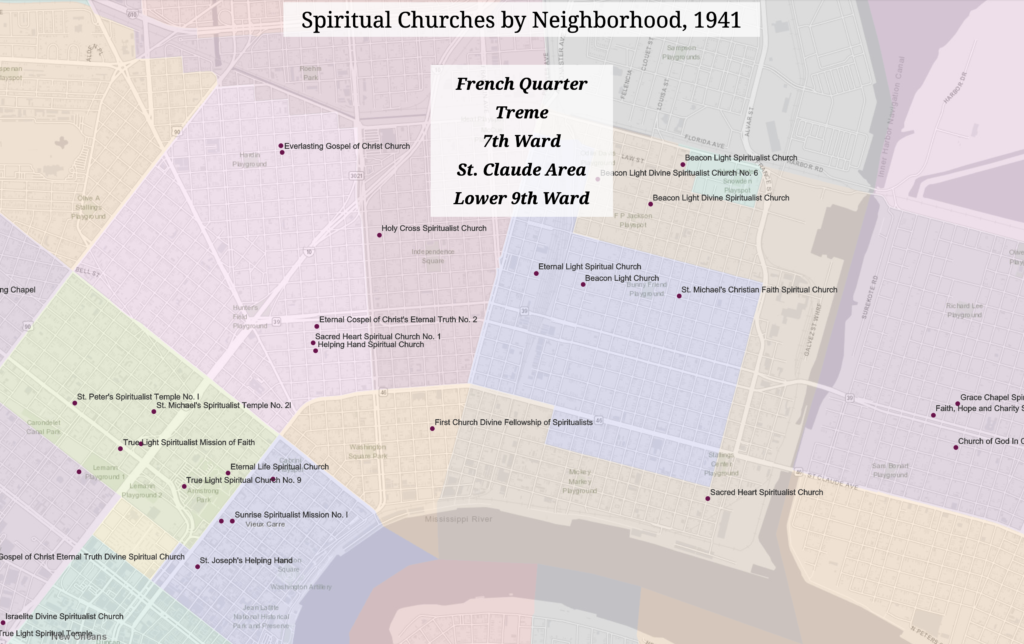

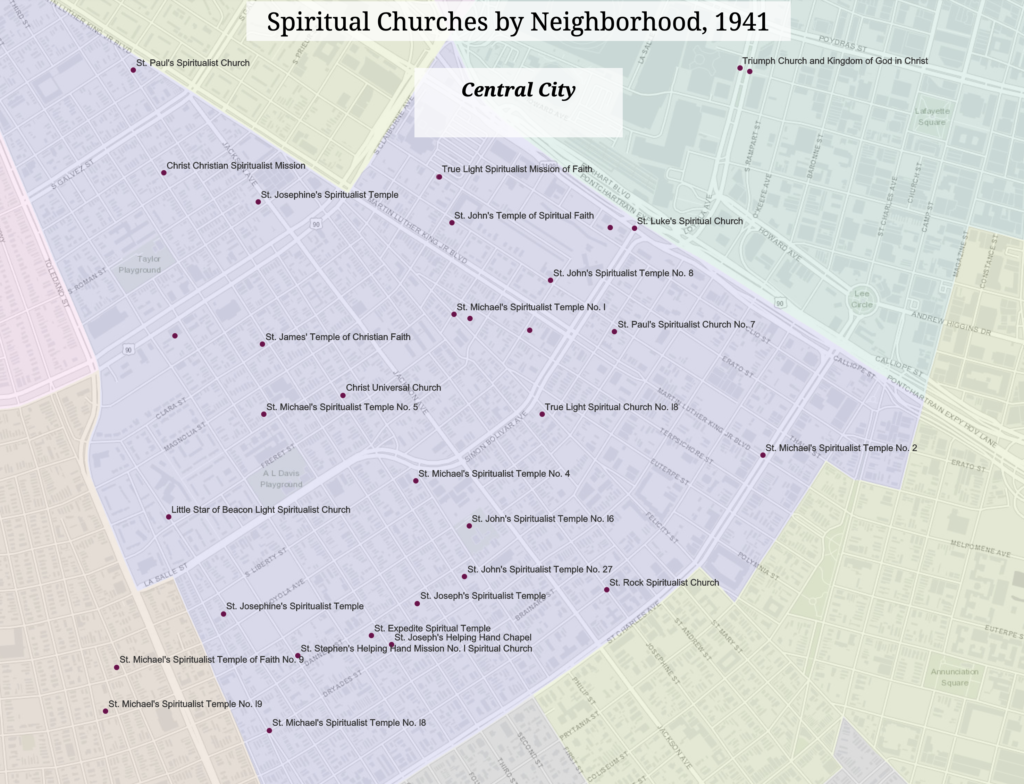

The scale and format of the data provided in the primary source document was not conducive to easy analysis. The information was arranged in alphabetical lists containing addresses and the names of religious leaders. This information was further subdivided by denomination and then by race. While somewhat useful, there were no indications regarding how these data points related to each other. Only after compiling, cleaning, and visualizing the data were patterns visible. In particular, the process of mapping the geolocated sites showed clear geographical evidence of the relative influence of each of the affiliations under study. Not surprisingly, Catholic institutions were spread across the entirety of the city. This appears to reflect the long-standing presence of Catholicism in New Orleans beginning with the first French settlers in the eighteenth century. The other denominations, however, more more tightly bounded and reflected patterns of settlement among different populations. The maps show that Jewish institutions were largely localized in a band running down St. Charles Ave., with outposts in Gentilly and Mid-City. Baptist churches are strongly clustered in the Mid-City, Gert Town, and Hollygrove neighborhoods and stretch out in an arc from Bayou St. John to the Lower Ninth Ward. The sites associated with Spiritual Churches are predominantly located in the Leonidas and Central City neighborhoods to the west and the French Quarter, Lower Ninth Ward, and St. Claude Area to the east. In the cases of the Baptists and the Spirituals, the neighborhoods in which these churches are located strongly correlate to regions with high African American populations.

Future Directions

This project is a good beginning and can be taken in multiple directions. The data, for example, can be analyzed statistically and spatially to see what further patterns emerge. These patterns can then be contextualized by, and help to illuminate, research in fields such as religious studies, urban studies, urban development, geography, race and gender studies, and regional studies (e.g. the History of New Orleans). These contextual studies would benefit from adding data on the religious leaders associated with each institution (priests, pastors, etc.) and comparing the neighborhood in which they lived with the neighborhood in which their church was located. Further, the geographic data locating the various denominations can be put into a larger social milieu by overlaying it with red-line maps. This type of comparative analysis would help shed light on the relative poverty levels within denominations. Finally, the data could be shared and expanded by making it available for contributions through sites such as History Pin.

Bibliography

Blevins, C. (2016). Digital History’s Perpetual Future Tense. In M. K. Gold & L. F. Klein (Eds.), Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016 (pp. 308–324). Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1cn6thb.29

Cohen, J. D., & Rosenzweig, R. (2005). Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from http://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory/

Historypin. (n.d.). Retrieved May 10, 2019, from Historypin website: https://about.historypin.org/

Robertson, S. (2016). The Differences between Digital Humanities and Digital History. In Gold M. & Klein L. (Eds.), Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016 (pp. 289-307). Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1cn6thb.28

Project URL

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=b3a2f898c0ac49819c6faf09e9d80603

Project GitHub Repository

https://github.com/GenevieveMilliken/WPA_Directory_of_Churches_New_Orleans_1941