Person: Katherine Groo

I first heard of Groo, who is a professor of film and visual culture at Lafayette College, through her controversial Washington Post piece in December 2018 titled “FilmStruck wasn’t that good for movies. Don’t mourn its demise.” The essay was in response to the then-recent announcement and subsequent outrage that the popular movie streaming service FilmStruck (run by Turner and Warner Bros. and known for its arthouse titles) would be shutting down. In the essay, Groo writes bluntly, “FilmStruck was never a library or a film archive. It was a for-profit streaming platform that provided access to those who could pay for it.” Groo goes on to discuss actual film archives and libraries, including some that also function as (free) streaming services, such as the Internet Archive and Kanopy. She notes that cinema tends to produce many, many artifacts that are not seen as valuable enough for preservation, and suggests that instead of advocating for the for-profit streaming service with its selection of classics, FilmStruck fans advocate for funding for film libraries and archives or other models that will provide open access to a broader collection of movies. The essay helped me to understand what libraries and archives can and should do, by exposing the biases of a streaming service that is at first glance structured much like an archive. More recently, Groo published a book called Bad Film Histories: Ethnography and the Early Archive, in which she discusses her interactions with ethnographic film fragments from the first few decades of cinema. Like her FilmStruck piece, Groo’s book is a fascinating look at archival theories and practices from the academic perspective of a film historian. Despite the fact that she comes from a film background and is not a trained archivist, Groo’s thinking has grounded my understanding of my place as an archivist, working with historians, researchers, and other patrons. She takes the idea of the archive and asks readers to consider alternatives to old models of value-based preservation and profit-based access. Groo discusses how deeply things are shaped by how information professionals organize, name, and share resources. In her FilmStruck essay, Groo writes that history is never a “comprehensive body of works tucked away in an archive,” and that there are always new ways of understanding what we think we know that are not dependent on canonical bodies of work, made canonical by individuals and forces of society not necessarily documented with the works themselves.

Place: Interference Archive

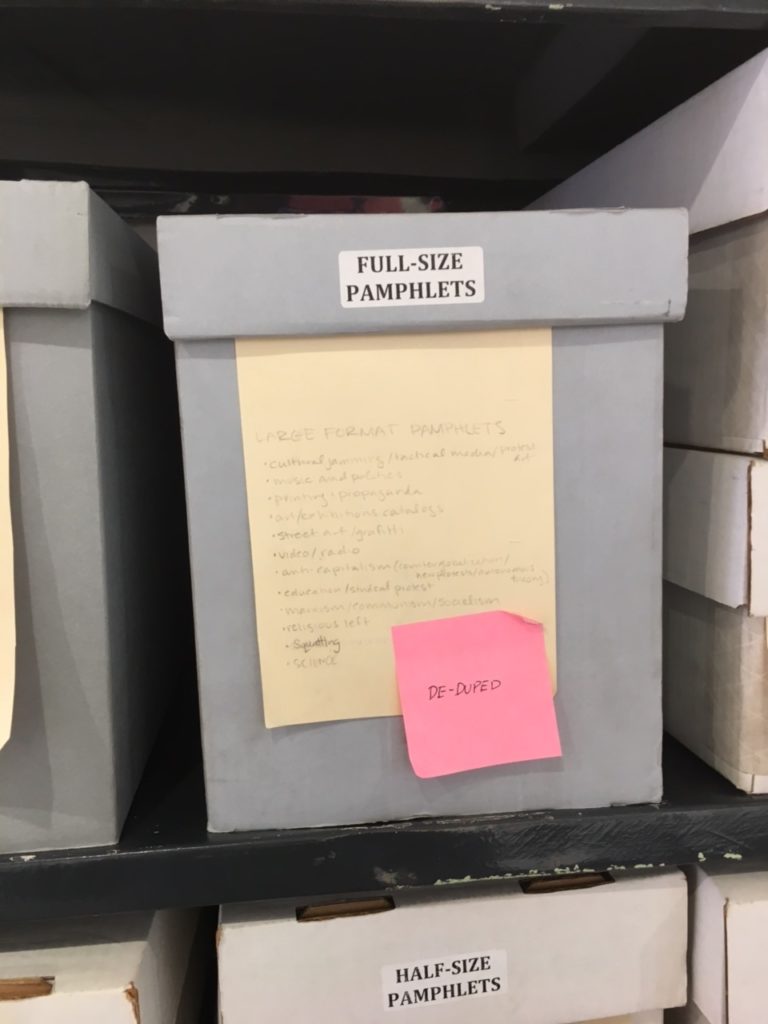

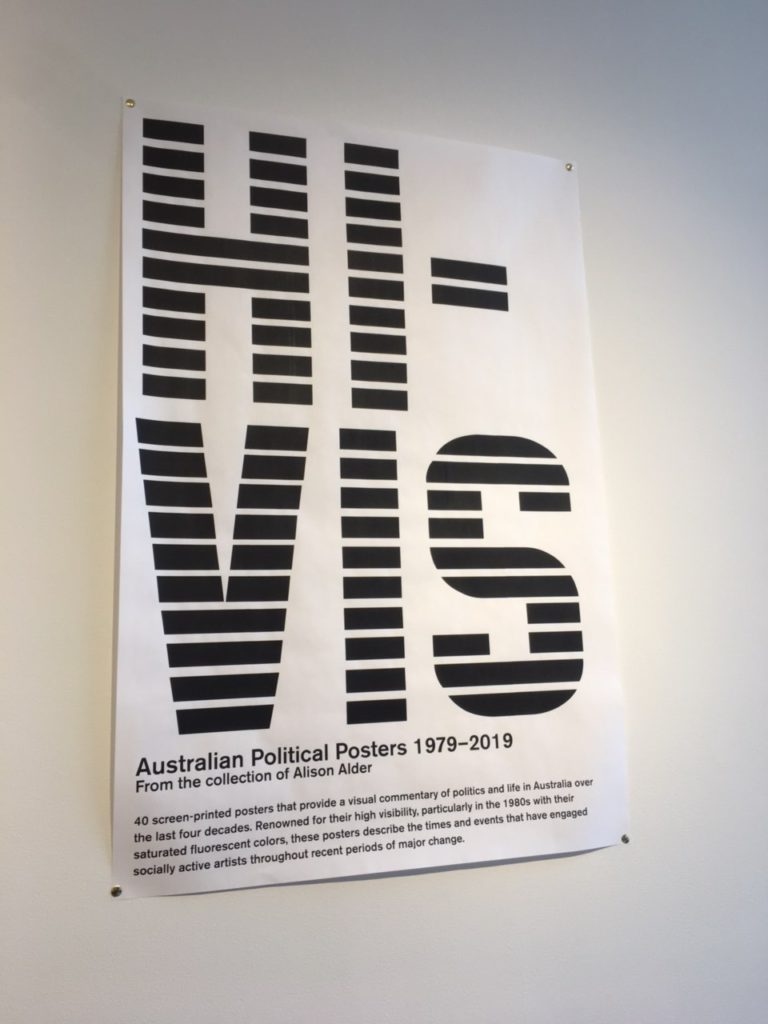

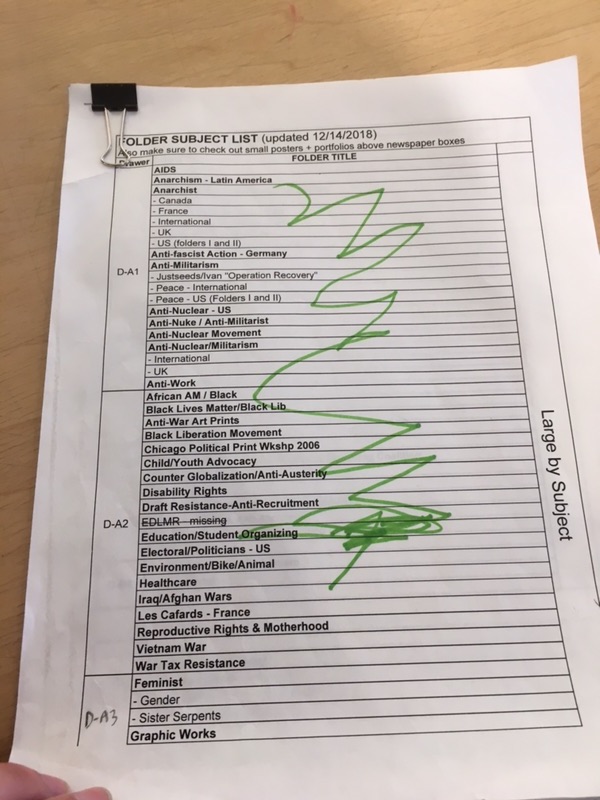

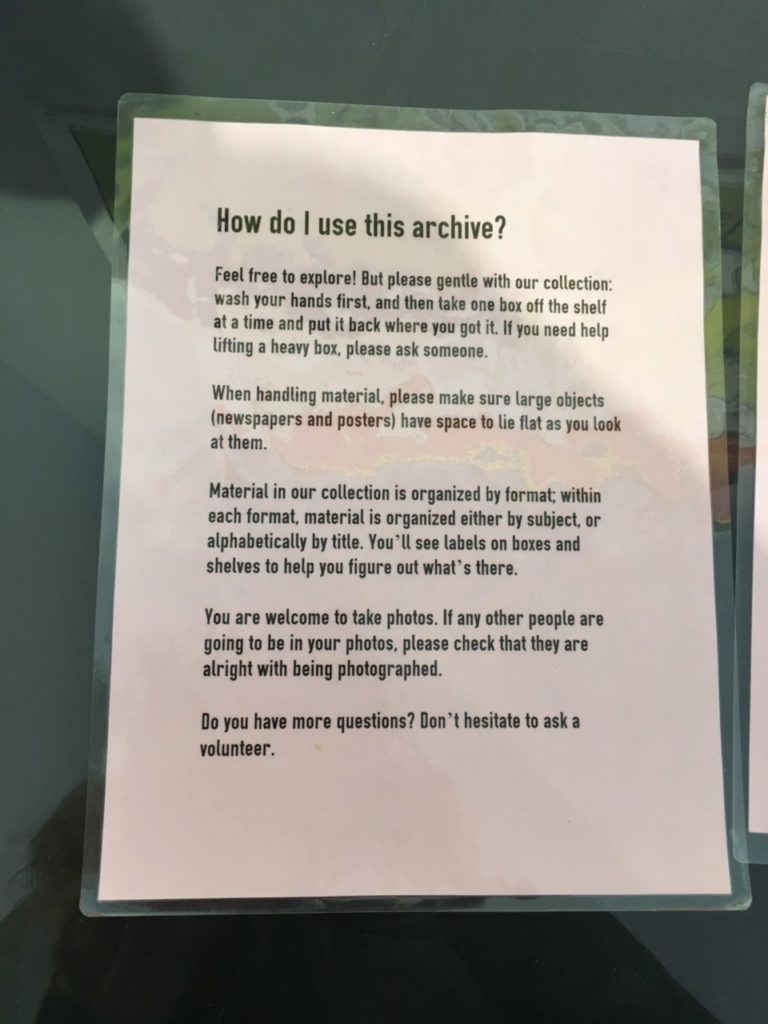

I was first introduced to Interference Archive, which is located in Park Slope, several years ago, and I have been volunteering there since. It’s a place that has shaped my idea of what archives can look like and how archivists can be community members and activists. Interference Archive is an entirely volunteer-run organization that collects archival materials related to social movements and makes those materials available in their open-stacks space. One of the most fascinating things about Interference Archive is their emphasis on accessibility to their materials. All of the collections, including things like posters, zines, buttons, books, and records, are available in their open stacks for any patrons to touch and interact with. For many people who have only interacted with archival collections through the barriers of academic or museum collections with all of their barriers, the openness at Interference is shocking. They also put on exhibitions and programs related to their collections or to relevant work being done by members of the community. The lack of institutional affiliation means that Interference Archive is able to have entirely independent programming. Their programs include workshops, speakers, film screenings, kids events called “radical playdates,” and many more types of events, expanding ideas of what role archives can play in a community. At Interference Archive, the collections are not behind barriers and used only for research; they are the totally integrated into present-day action. As an archivist, I want to think about how the work I am doing is best not just for the materials I work with, but for the people those materials serve. The Archive does not simply house political content and move on; its structure, goals, and events reflect the radical potentials of the materials they collect.

Thing: Lost & Found

Another inspiration to me as an archivist that comes from outside the archives field is Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative. Lost & Found is a project and publication based at the CUNY Graduate Center, with doctoral students in their Enlish program serving as researchers and editors. Focusing mostly on 20th century American poets, Lost & Found editors use archival materials to research their subjects, and to draw previously unpublished works, correspondence, journals, lectures, and writings in translation into publication for the first time. The series is published annually as a collection of chapbooks—previous issues include works from Audre Lorde, June Jordan, William S. Burroughs, Kathy Acker, Diane di Prima, and more—but research originally done for Lost & Found also frequently turns into book-length publications. The series’ founder, Ammiel Alcalay, says that the principle behind the series is for researchers to “Follow the person.” This is a pretty surprising position for many literary scholars to take—one that at first ignores the canonical context for a writer’s work in the form of literary “schools,” periods, or groups of associates—and instead focuses first on the hard evidence of an individual’s archival output. This series is so exciting to me as an archivist because it integrates scholarly research and archival work. It’s an example of how archivists can help open up new ways of seeing subjects and people.

Resources:

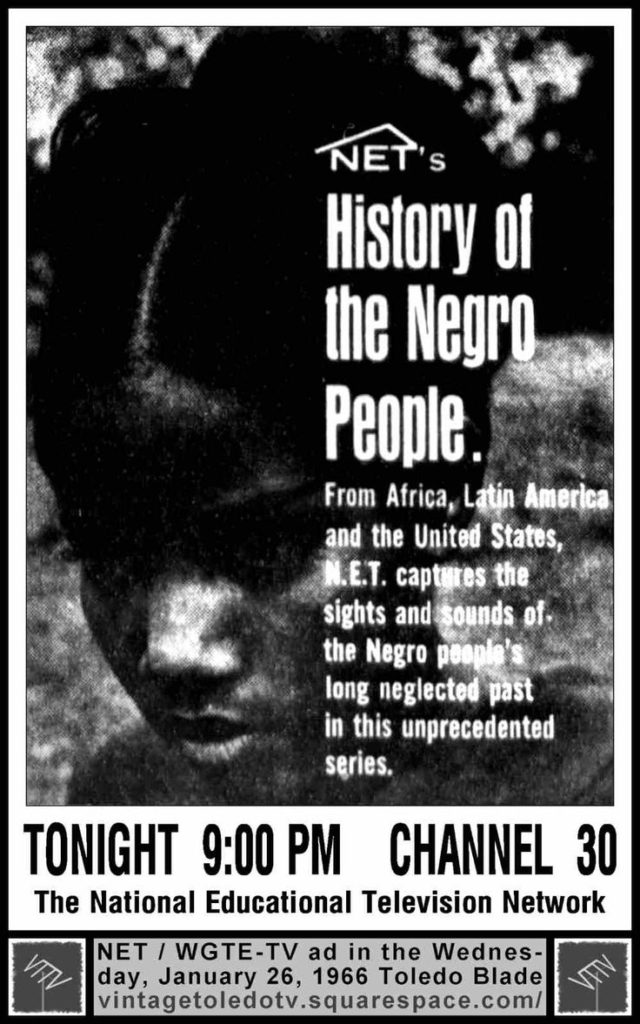

Groo, Katherine. Bad Film Histories: Ethnography and the Early Archive. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

Groo, Katherine. “FilmStruck wasn’t that good for movies. Don’t mourn its demise,” The Washington Post, 3 Dec. 2018.

Interference Archive.https://interferencearchive.org/

Lost & Found, The Center for the Humanities. https://www.centerforthehumanities.org/lost-and-found