On September 26, 2019, I attended the NYC Media Lab Summit held in downtown Brooklyn. The mainstage program took place at the New York City College of Technology (City Tech CUNY) for the first half of the day. The second half of the day was dedicated to interactive demos and workshops and took place at both City Tech and the New York University (NYU) Tandon School of Engineering.

NYC Media Lab describes itself as dedicated to “driving innovation and job growth in media and technology by facilitating collaboration between the City’s universities and its companies” (About – NYC Media Lab, n.d.) Pratt Institute is part of NYC Media Lab’s consortium with goals “to generate research and development, knowledge transfer, and talent across all of the city’s campuses” (About – NYC Media Lab, n.d.), which also includes The New School, School of Visual Arts, Columbia University, NYU, CUNY, IESE, and the New York City Economic Development Corporation. Member companies of NYC Media Lab include Bloomberg LP, Verizon, The New York Times, and NBCUniversal, to name a few.

The Media Lab Summit held itself like a typical conference, where you check in to receive your name badge upon arrival and are treated to coffee and pastries. Then everyone takes their seats before the main program begins in the auditorium where the Executive Director of the program, Justin Hendrix, makes his welcome address and does introductions.

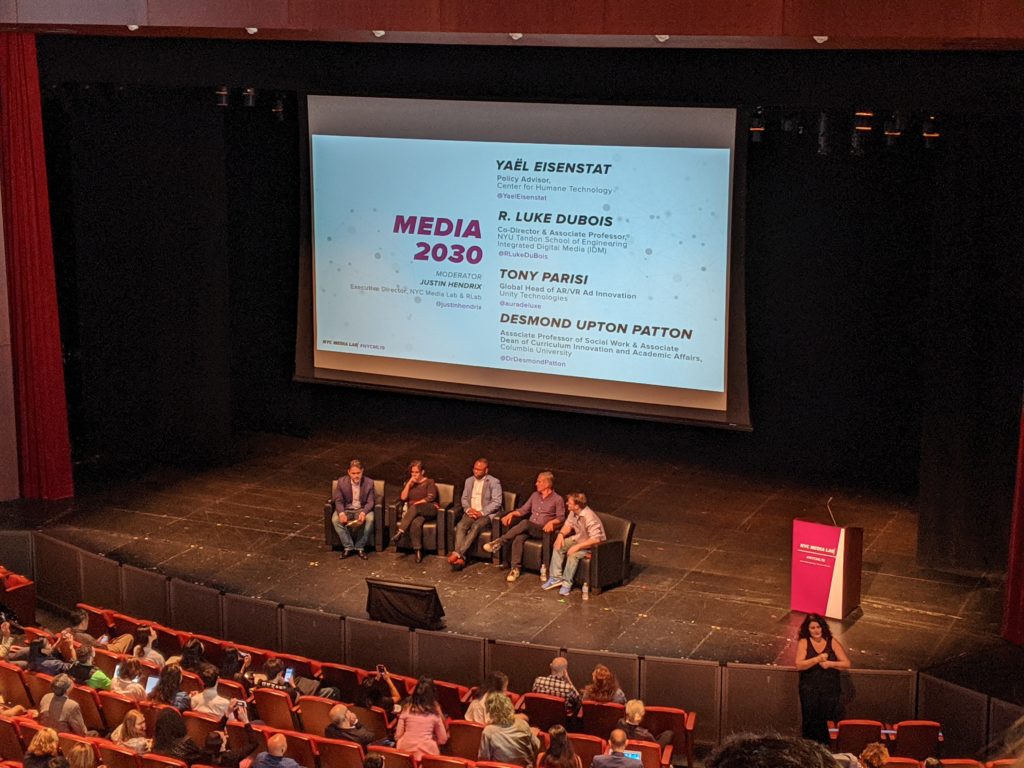

Up first was the Innovation Panel, which featured speakers Yael Eisenstat, R. Luke Dubois, Desmond Patton, and Tony Parisi. The panel featured a mix of academics and professionals who all addressed the topic of artificial intelligence, or AI. It was interesting to hear that everyone agreed that AI is the future but that they all held concerns about whether it will be accessible to all. Another potential issue that was brought up in relation to AI is what seems like our current overdependence on data. One panelist raised serious concerns about this overdependence and worried whether this could lead to the complete disregard of an innate human characteristic, which is critical thinking. All panelists agreed that critical thinking is essential and sees it playing a key role throughout the use of AI and other technological advancements.

What I ultimately took away from this Innovation Panel was that critical thinking is needed now more than ever. I think we have always understood that critical thinking is crucial as it is what keeps us human. AI is capable of making decisions for us, but the ability to be able to critically think about the potential impacts of our decisions and asses our judgments remains entirely human. This emphasis on critical thinking reminded me of the Phoebe Sengers reading in which she also discusses machine culture but stresses that science and the humanities need “to be combined into hybrid forms” as “neither is sufficient alone” (Practices for Machine Culture, n.d.). Like the panelists, Sengers recognizes the strengths in both and how each can complement the other, especially in AI.

Next up were the showcases. The showcases were meant to present and demonstrate projects, prototypes, and startups created by students and faculty from NYC Media Lab programs. Two of the showcases that stood out to me the most were a subway accessibility app for the blind and a retina technology startup.

Students from NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program created an app called Access to Places with the goal to make subway stations much more accessible for the blind. The app utilizes iOS’ text-to-speech voiceover technology to provide information such the location of entrances and exits, service delays or changes, and arrival and departure times. Notifications also help the blind to navigate around station layouts.

Retina Technologies was formed by medical students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The startup aims to change the way people access ophthalmologists in both urban and rural areas. Through the use of virtual reality headsets, the startup hopes to increase access to ophthalmologists for those who cannot easily visit one in rural areas while also improving the patient experience for those in urban areas.

Access to Places and Retina Technologies both stood out to me the most because of the users that they were designing for. Instead of creating a product that catered to the majority of the population, they reached out to those with specific needs that often get neglected in the startup and tech conversations. I immediately thought of the Sasha Costanza-Chock paper on “Design Justice” and the discussion on who designers are actually designing for. The majority of startups and apps tend to assume the average user is able to access or use a product without any accommodations, much like how Costanza-Chock discusses that designers “assume” that “a user has access to a number of very powerful privileges” (2018). Visiting an ophthalmologist or getting onto the subway without any trouble are privileges that most designers tend to assume users have. Access to Places and Retina Technologies decided to instead focus on the needs of these specific user groups rather than create another app or startup that assumed they were just like every other user.

Many innovative and creative projects were demonstrated, and I was in awe over it all, but it was the discussions that were held that enlightened me. What I took to be the overall theme of the Media Lab Summit was accessibility and the continued mission to make this collaboration between media and technology available to all. I still believe that technology has this amazing potential to change and impact lives, but we must make it available to everyone to see it happen. The Media Lab Summit and our class discussions and readings only continue to highlight this necessity and how we as information professionals cannot simply ignore it as technology advances.

References:

About – NYC Media Lab. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://nycmedialab.org/about.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2018). Design Justice: towards an intersectional feminist framework for design theory and practice. DRS2018: Catalyst. doi: 10.21606/drs.2018.679

Sengers, P. (n.d.). Practices for Machine Culture: A Case Study of Integrating Cultural Theory and Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved from http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/usr/phoebe/mosaic/work/papers/surfaces99/sengers.practices-machine-culture.html.