Two weeks ago, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, Library, and Research Collections invited university students and faculty to come learn about the library and archives, what they have to offer, along with an introduction to their online catalog. The event began with a series of presentations, an introduction to the Archives and Library, overviews and discussion of MoMA’s exhibition history pages on moma.org, electronic resources, archival processing, library cataloging, and artists’ books. Before attending, I had expected a very hands-on experience of the inner workings of the library and archive, gaining information about and insight into how they acquire and catalog their books, objects, and information. What I got instead was a comprehensive walk through of the MoMA’s online catalog and services available to the public both physically at the library as well as electronically.

After introducing ourselves to the library staff and them doing the same with us, we were then introduced to the library; what it is, who can access it and how, and what is all in the library. An integral player in all this information is the MoMA’s online catalog. So what is there to know about MoMA’s library and their catalog? The most important thing to know about the MoMA’s catalog is not that it is completely online, nor is it the ease of searching everything from books to auction catalogs to archives. The most important part is that they decided to name it DADABASE and that is hilarious. In all seriousness what we learned as library and art history students about the DADABASE could easily be learned through some individual exploration of the museum’s page though often the existence of it falls under the radar of the average layman. That was a long-winded way of saying that I had no idea I had access to MoMA’s library and I had no idea what treasures it held and I am positive that I am not an anomaly in this scenario. It is a paradox of accessibility- a tool anyone can use, if only they know where to look for it.

Anyone who has access to a computer and internet has access to the DADABASE and anyone subsequently can make an appointment to see specific books or materials at the library through the website. We were shown during the meeting that the online catalog is much like any other online one search catalog. One of the librarians working at MoMA walked us all through searching the finding aids for the MoMA archives and their holdings.

As interesting and comprehensive as it is, the catalog is not perfect. We explored some of the errors in searching that can happen which are solves simply by being in the know, or of course consulting a librarian. In some cases, the catalog is tricky to search unless you are in the know about its organization. For example, in the records for the finding aids in the archives section, the container lists, though mostly great, if you search by the name of a person who was involved with press interviews you may get some results but others are hidden and more or less unsearchable. This flaw is due to the fact that the high volume of these interviews lead them to being cataloged by last initial. For example when looking through the Rona Roob Papers, and scrolling down to the “Collectors and Collecting,” a portion of this section stops being organized by individual collectors and begins with the truncated “collectors A-F.” The only way to find this document based on a collector that is in that “A-F” section is if you know the year and papers where the person you’re looking for would be recorded. The individual collectors in this section are not individually cataloged or tagged like in the sections organized by name instead of initial. This however, is really the only big flaw with how they online archive catalog is laid out and is easily solved by enlisting the help of one of the librarians.

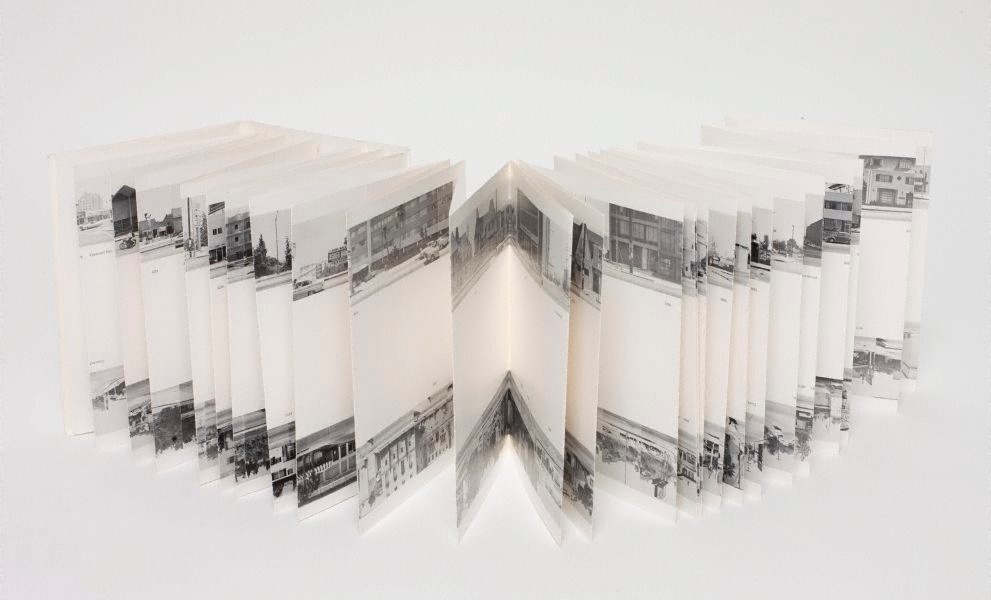

Along with exploring and understanding the catalog and what is available to us as users, we learned about MoMA’s collection of artist books. They have a large variety of books that were created with the intention of being an artist book but some are a little more liminal. Something I found interesting and a bit unorthodox was how they decided to catalog artists books. Again, most are easy as most are sold and created as artists books but something MoMA does differently is catalog books that aren’t artist books per se, but are instead artist books because they exhibit artistic elements. One example is a midcentury advertising catalog of which they have many issues. They would have the catalog regardless because it contains interesting and relevant information to MoMA but they decided to catalog it as an artist book instead of a magazine because the cover has interesting and unique design elements that were not necessarily common for a magazine of its type.

The Museum of Modern Art Archives, Library, and Research Collections event was a little different than what I had gone in expecting. Regardless, I learned a lot about the MoMA archives that I truly wish I had known sooner. I know however, that they will be a great resource come thesis season for history of art grad students including myself.