Author: swarga

Archives Week: Franklin Furnace

When does a book become a danger to itself? Franklin Furnace Archive deals with this question on a regular basis. Their growing archive consists of artists’ books that are made from a plethora of materials and take on many forms – making preservation difficult. On October 23rd I attended the Archive’s open house to see for myself what these “books” look like and how they are stored.

The head archivist, Michael Katchen, opened with a brief history of the archive. Franklin Furnace Archive was founded by Martha Wilson in 1976, focusing on the collection of artists’ books and performances. In 1993, MoMA acquired their collection – contingent on certain terms, and in 1997 they transformed from a “physical exhibition space into an Internet-based one”1. In 2014, the archive moved to its current home on the 2nd floor of the former building of Pratt’s School of Information.

The terms agreed upon in this 1993 acquisition are incredibly interesting: whatever books are accepted into the Franklin Furnace in the future have to be accepted into MoMA’s archives as well,becoming part of their permanent collection. So, what are the criteria for a book to be accepted? Michael says that as long as the artist believes that what they are submitting is a book, then it is so. This means that I could submit two copies of a work, in any form whatsoever, and finally get my work into MoMA.2

Michael went on to explain technical details about the archive; how items are preserved, and how items are accessed. The nature of the collection means preservation is challenging. Books in the collection may not resemble books at all, and their materials can degrade easily. Books that fit into certain dimensions are kept in phase box enclosures, others are kept in whatever containers they were sent in. An example of a more unorthodox enclosure were two “books” that Michael accepted into the archive last year. He walked over to a shelf and pulled down two plastic white paint buckets, opened them, and removed two paint-dipped tomes. They were more form than text, and totally unreadable, but they push what the boundaries of what an artists’ book can be.

Many of the older books and book forms have accompanying video documentation from related performances by artists, which are accessible through their online event archives3. The physical items from the early days of the archive have time-based media documentation attached to them. To preserve those films, Franklin Furnace has a digitizing workstation to produce preservation copies and DVD’s.

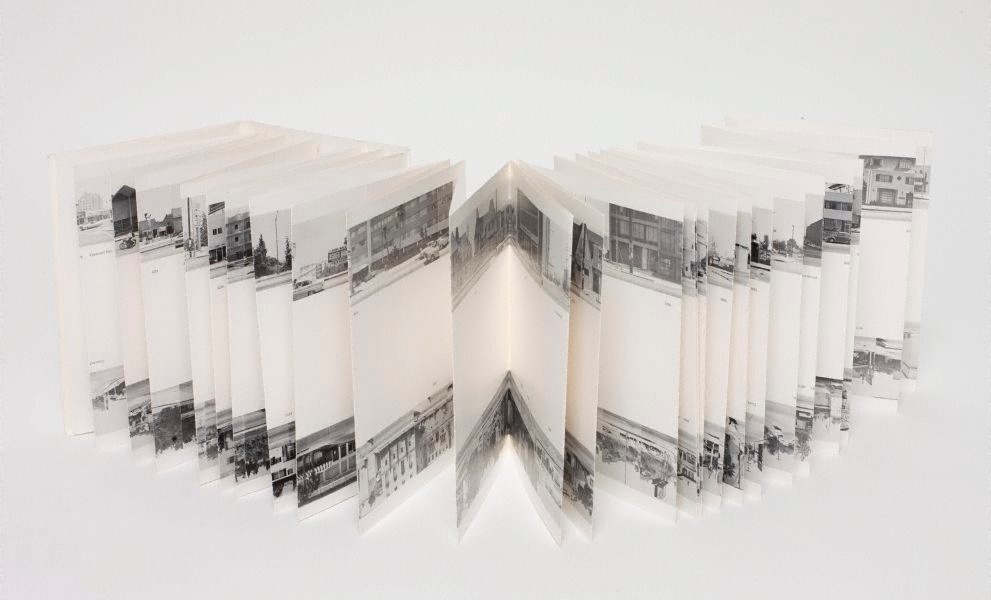

Edward Ruscha, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1966

Anyone can go to the archive and experience the books. The only requirement: a clean set of hands, and the whole archive is at your disposal. I was able to touch and flip through Ed Ruscha’s original 1966 work, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, which is a 25-foot long accordion-folded book. Michael’s estimate of the work: around $20,000 or so. It was an empowering experience to be in such close contact with the works at Franklin Furnace, and I appreciated how much access they grant to the public.

1Franklin Furnace. “History & Collections.” Accessed October 25, 2017. http://http://franklinfurnace.org/research/index.php

2“Franklin Furnace Artists’ Books Collection.” Accessed October 25, 2017. http://franklinfurnace.org/research/moma-FF-artist_book_collection.php.

3Franklin Furnace. “Event Archives.” Accessed October 26, 2017. http://franklinfurnace.org/online_event_archives/index.php.

New Dimensions of Preservation

When does an object become information? 3D scanning has created new dimensions in the field of preservation but presents new cultural challenges. In the following I will examine the practice of 3D scanning and printing by cultural institutions, address the possibilities this process offers for preservation at large, and consider some questions that have arisen from its use.

3D scanning is now more affordable and accessible than ever before and offers the opportunity for audiences to interact with historical objects in new ways. In addition to contemplating the exciting new forms in which this technology can give the public a more active role in preservation, I believe it is important to meditate on a few issues that this process may pose. How does 3D scanning change the idea of ownership and authenticity of an object? What cultural disruptions have developed as a result of the emergence of this technology, and what has it offered solutions to?

3D technology can activate public engagement by rendering otherwise off-limits objects into digitally malleable material. Dedicated social platforms1 and cultural workshops beg the public to participate in the “consumption of heritage, and re-inscription of meanings that are transferred to heritage objects.”2 Digital surrogates of objects can give curators the chance to initiate public interaction with a collection in a more hands-on way, offering the chance to participate in the preservation of an object and safely play with historical forms. One institution that has organized this technology into a workshop is the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg. In 2015, the museum conducted a workshop in which participants were given supervised access to original artifacts and introduced to 3D basics such as scanning, computer-editing, and 3D printing.3 Once the participants finished scanning the artifacts they took the digital models and were taught how to edit them in practical and creative ways. This workshop invoked a sense of play with history and asked those present to become digital craftsmen. As Michele Valerie Cloonan writes: “when these cultural remnants are placed into a contemporary context, something new is created.”4 A participant that was present at the workshop with his daughter re-mixed two sculptures together by taking the “hard-edged expression of Wilhelm Freddy’s Sphinx” and meshed them together with the “soft, organic features of Wiig Hansen’s Seated Woman.”5 This case is an example of how new forms of cultural production can be created from archives and collections, and foster the transmission of heritage between generations.

In war-ridden parts of the world, however, 3D scans have become part of the discourse regarding the preservation of endangered cultural property. The war in Syria is a gruesome example of how warfare has given rise to the use of “digital technology as a tool of preservation—both real and virtual.”6 Before being destroyed by the terrorist group ISIS, the Roman arch of Palmyra was thoroughly scanned and digitized into a 3D file by a team from UCLA.7 This reaction to the deliberate erasure of history was a direct “response to the threat of destruction and loss.”8 The information from those scans were used in 2016 to 3D print a replica of the arch based two thirds of its original dimensions and was installed in New York’s City Hall Park for one week. However, the recreation was devoid of on-site contextual material and prompted mixed reactions, with some saying that it was a form “digital colonialism.”9. In an article for Forbes journalist Sarah Bond raised a critical point about the ethics of the duplicate arch:

“There … needs to be more concerted efforts to create knowledge about the object on its new site. Should the NYC public not also be toald, for instance, about how ISIS killed a celebrated Syrian antiquities expert, Khaled al-Asaad,and then hung his body from the ancient Roman columns at Palmyra? Or more about the history of the arch itself? “10

3D recreations pose challenges regarding provenance, history, and how to show respect for the original.

In international politics, 3D scans have become a central element of proposed solutions to spats between countries regarding repatriation. An ongoing dispute between the governments of the UK and Greece about the ownership of the Parthenon Marbles is to note. About thirty percent of the surviving Parthenon Marbles are held by the British Museum and have been in their permanent collection since early 19th century after being chiseled from the Acropolis and shipped to England by Lord Elgin – who had express permission from Greece’s colonial occupiers, the Ottoman Empire. 11Greece’s government and cultural institutions have been pushing the international community to recognize their repeated calls for the Elgin Marble’s repatriation to Athens. Currently, the Acropolis Museum has on display “plaster casts of the sculptures housed in London… interspersed with original pieces Elgin left behind.”12 One possible way to ease the tension might be to provide the British Museum with 3D surrogates, as Paul Mason proposes in his article “Let’s end the row over the Parthenon marbles – with a new kind of museum.”13 An interesting idea, but possibly too idealistic in the face of such a complex problem regarding cultural property. While the calls for the statues repatriation may go unanswered for the foreseeable future, they have nevertheless created “a new kind of cultural property—a kind of meta-cultural property that represents a shared global culture that we are creating today.”14

As objects are brought over into the digital realm the possibility for a more shared and democratic global culture increases. Artifacts that would otherwise be hidden away can show their face on an illuminated screen and be remixed in multiple dimensions by the public. Endangered historical sites and objects can be captured digitally and provide a blueprint of the past if the originals are destroyed. There are many ways in which 3D scanning can aid preservation, although the issues it presents to society are even more numerous. I hope that in the future this technology will generate new types of interaction with history and give the world a more collective sense of culture.

REFERENCES

1 Sketchfab. Accessed September 20, 2017. https://sketchfab.com/.

2 Dalbello, Marija. “Digital Cultural Heritage: Concepts, Projects, and Emerging Constructions of Heritage.” Proceedings of the Libraries in the Digital Age (LIDA) conference, May 25 – 30, 2009, 2.

3 Jakobsen, Lise Skytte. “Flip-flopping museum objects from physical to digital – and back again.” Nordisk Museologi 1, no. S (2016): 121-37. March 7, 2016. Accessed September 20, 2017. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5617/nm.3068.

4 Cloonan, Michele, Valerie. “W(h)ither Preservation?” The Library Quarterly 71.2 (2001): 231.”

5 Jakobsen, L. S. (2016), 17.

6 Silberman, Neil. From Cultural Property to Cultural Data: The Multiple Dimensions of “Ownership” in a Global Digital Age, 21 INT’L J. CULTURAL PROP. 365, 368 (2014), 4.

7 Bond, Sarah. “The Ethics Of 3D-Printing Syria’s Cultural Heritage.” Forbes, September 22, 2016. Accessed September 21, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2016/09/22/does-nycs-new-3d-printed-palmyra-arch-celebrate-syria-or-just-engage-in-digital-colonialism/#46951fde77db.

8 Cloonan, Michele, Valerie. “W(h)ither Preservation?” The Library Quarterly 71.2 (2001): 236.”

9 Bond, “The Ethics Of 3D-Printing Syria’s Cultural Heritage.” 2016.

10 Bond, “The Ethics Of 3D-Printing Syria’s Cultural Heritage.” 2016.

11 “Elgin Marbles: Commons motion urges return to Greece.” BBC News, March 9, 2015. Accessed September 21, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-31788821.

12 Poggioli, Sylvia. “Greece Unveils Museum Meant For ‘Stolen’ Sculptures.” NPR, October 19, 2009. Accessed September 22, 2017. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=113889188.

13 ” Let’s end the row over the Parthenon marbles – with a new kind of museum.” The Guardian, February 15, 2015. Accessed September 23, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/commentisfree/2015/feb/15/way-to-end-row-over-parthenon-marbles-virtual-reality.

14 Silberman, From Cultural Property to Cultural Data: The Multiple Dimensions of “Ownership” in a Global Digital Age, 4