The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, Inc. is a unique professional organization, due in part to the wealth of cultural, academic, public & private institutions located in NYC that are home to professionals in the archives field. ART produces educational programs, provides support for professional development, advocates for historical preservation, and gives archivists the opportunity to network at social events. At the start of their fall season, ART hosted a two-part series revolving around art and archives pertaining to David Wojnarowicz. The first program—New Approaches to Artists’ Archives: The Artist Archives Initiative & The David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base—was a talk given by NYU Professor and MoMA Conservator Glenn Wharton along with Special Collections Librarian Nicholas Martin at Fales Library and Special Collections, NYU Bobst. The talk was followed by a brief lecture from Hugh Ryan, curator of The Unflinching Eye: The Symbols of David Wojnarowicz, an exhibition at the Mamdouha Bobst Gallery comprised of archival material from the Fales Collection. The second program—History Keeps Me Awake At Night: David Wojnarowicz Exhibition Tour—occurred the following week at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The tour was guided by Tara Hart, a graduate of Pratt’s MSLIS program who is currently the Archives Manager at the Whitney. The tour also featured an introduction to the Whitney and it’s facilities by the Director of Research Resources, Farris Wahbeh. I attended both of these events, including the networking and “happy hour” portions that followed.

Part I

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at NYU, is a cozy space featuring antique card file cabinets—some of the Fales Special Collections still utilizes the card catalog—and wooden bookcases with glass doors. Behind the bibliographical threshold lay the archives; notably, The Downtown Collection, which holds archival material related to the LES and SoHo art scene as it developed from the 1970s through the 1990s. Within this collection, amongst other treasures, are the David Wojnarowicz papers, ca. 1954-1992. Consisting of 128 linear feet of documents, from journals and interviews, to

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at NYU, is a cozy space featuring antique card file cabinets—some of the Fales Special Collections still utilizes the card catalog—and wooden bookcases with glass doors. Behind the bibliographical threshold lay the archives; notably, The Downtown Collection, which holds archival material related to the LES and SoHo art scene as it developed from the 1970s through the 1990s. Within this collection, amongst other treasures, are the David Wojnarowicz papers, ca. 1954-1992. Consisting of 128 linear feet of documents, from journals and interviews, to phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today, The David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base (DWKB), the premiere project of the Artist Archives Initiative (AAI).

phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today, The David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base (DWKB), the premiere project of the Artist Archives Initiative (AAI).

The Artist Archives Initiative is an ongoing experiment in contemporary art which seeks to address a need for evolving information resources based on cooperative efforts between artists and scholars. In pursuit of this goal, the AAI produced the DWKB, not only with the artists’ papers, but by conducting interviews with artists, friends, and others who knew Wojnarowicz; inviting scholars to submit their research and writings; and by choosing MediaWiki software to build the database. MediaWiki software is open-source, allows for low-cost maintenance, provides a strong user community, and has a hierarchical menu that allows researchers to search the database “laterally” through text searches and links within articles to other pages, including more DWKB pages, outside resources, and references.

I believe this project is an example of a strategic development in the application of archival materials towards increased accessibility, discoverability, and interdisciplinary collaboration. The next project that the AAI has underway is the Joan Jonas Knowledge Base. Joan Jonas is a performance artist who is still very active. She lives closely with her personal archive, and because of this, she can be directly involved in the development of her own Knowledge Base. The iterative aspects of performance art pose an interesting challenge for Wharton and co-creator Deena Engel; multimedia documentation and the potential for years or decades between performances of the same piece, adds an element to the project that was absent from the scope of the DWKB. Additionally, the Joan Jonas Knowledge Base will not be developed with the benefit of content from a pre-existing archive.

In respect to the ART event itself, the talk with Glenn Wharton and Nicholas Martin was informational, conducted in conjunction with a slide presentation, and allowed for time at the end for questions. It was a pleasure to hear Hugh Ryan, the curator of the archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display.

archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display.

Downstairs in the Mamdouha Gallery, two tables had been prepared with concessions; wine, seltzer, fruit & cheese platters, and truffles that were handmade by the Program Coordinator, Amye McCarther. Treats were well-displayed and enjoyed by the event attendees. I made a point to discuss ART programming at-large with several professionals in attendance who gave reviews of past events along the lines of, “high-end”, and “always different, but always good.”

Part II

Meeting in the lobby of the Whitney, ART members and volunteers formed a group around the Director of Research Resources, Farris Wahbeh, who offered an abridged history of the museum, focusing on it’s origins and architectural provenance. Shortly after, the group followed Archives Manager Tara Hart up to the exhibition, David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake At Night.

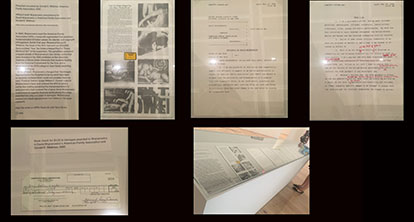

Among the first works in sight is an archival object that Nicholas Martin would refer to as “the big loan” during one of my subsequent tours of the Fales Collection—a Rimbaud Mask circa. 1978,  which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.

which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.

These documents, again, on loan from the Fales, are evidence of one of Wojnarowicz’ contributions to defending artists’ rights, and a sad reminder of the value that the American court placed on his art. At the end of the text accompanying the documents in the vitrine was a prompt for the viewer to engage with yet another archival component—to listen to Wojnarowicz discuss the trial and his art practice with Terry Gross in a 1990edition of Fresh Air.

It was apparent to me that collections of primary source materials were integral to the present-day curation and exhibition of David Wojnarowicz’ work. Additionally, the presentation of archival materials enabled audience members to hear the artist’s voice and to learn about the politics and realities facing Wojnarowicz and his community at the time.

After the museum, the ART group reconvened for refreshments at a nearby bar. I was able to engage in conversation with McCarther, a practicing digital archivist who once participated in a Joan Mitchell Foundation CALL pilot program in Houston. CALL, which stands for Create A Living Legacy, provides resources to the public, supports late-career artists considering organizing their professional records, studios, and archives, and educates emerging artists who share these concerns in assisting older artists. It’s clear that a program like CALL operates on the opposite end of the spectrum compared to a project like the Artist Archives Initiative. However, it was helpful to participate in industry-relevant discussions and to meet like-minded individuals.

References

References