On Thursday, February 28th, NYU Tandon School of Engineering held a live streaming event featuring a talk given by Netflix’s Director of Machine Learning, Tony Jebara. The topic covered was “Machine Learning for Personalization”, which Jebara provided company use cases and solutions for content personalization.

Netflix, a streaming media-service, is well regarded within the machine learning field for developing impressive machine learning models that incorporate advanced feedback mechanisms to train and improve those models.

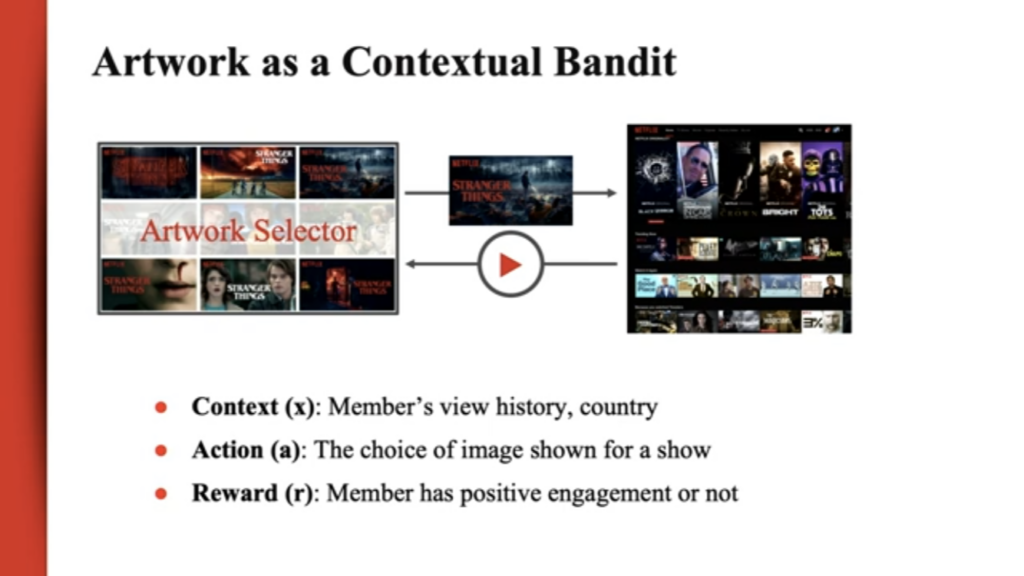

According to the Director of Machine Learning, Tony Jebara, every Netflix user’s experience is unique across a range of personalized content. A few examples of personalized content provided by Jebara were rankings, homepage generation, promotions, image selections, searches, advertisement displays, and push notifications.

Content Personalization

Content personalization is a technique leveraged by many companies, across many industries, for the business of either creating content, distributing it or both. Content encompasses everything from online articles to advertisements. In Digital Disconnect, McChesney describes that the popular digital method “personalizes content for individuals, and the content is selected based on what is considered most likely to assist the sale” (p.157).

Entrepreneur lauded Netflix and other media companies who are successfully leveraging machine learning to develop custom experiences but notes a dichotomy which plagues user’s and their preferences. The trade-off between conveniently custom experiences or inconveniently anonymous reintroductions. On one side, users face issues surrounding privacy or unpleasant information dictation.

Opposite to their praises as personalization gurus, Fast Company highlighted some of the negative criticisms Netflix has also received. When companies curate the content users consume, there’s a risk of receiving biased information whether it be political or racial. Berkowitz opens with, “How companies advertise to you says a lot about how they see you” when referring to the racial bias in the algorithms used by not only Netflix, in this case, but many of the other companies working to deploy advanced content personalization algorithms.

“Filter Bubbles”

Regarding the politically charged dictation of content, Castells remarks, “The networks themselves reflect and create distinctive cultures. Both they and the traffic they carry are largely outside national regulation. Our dependence on the new modes of informational flow gives to those in a position to control them enormous power to control us. The main political arena is now the media, and the media are not politically answerable” (p. 34).

McChesney adds how these practices also lead to an issue he considers the “personalization bubble” or what he specifically alludes to as the “filter bubble” (p.157). Users are trapped in an experience they believe to be unique or new but is perpetuated by the same content delivery—just done differently (p. 70).

McChesney references Eli Pariser’s The Filter Bubble: How the New Web is Changing What We Read and How We Think when stating, “Pariser’s Filter Bubble documented how the Internet is quickly becoming a personalized experience wherein people get different results on Google searches for identical queries, based on their history” (p.157).

When Netflix Intervenes

In his talk, Jebara claimed that “prediction is valuable but actual intervention is what we want to understand.” Their algorithms are two-fold—ensuring that experiences are uniquely specific without providing recommendations that are too specific, which may lead to either a negative user experience and a potential unsubscribe from the service.

We’ve all experienced moments of interacting with a digital platform that, over time and with enough data aggregation, begins to recommend content or display ads across devices and sites outside the ownership of the originating platform. If frightened enough, we may have even gone as far as to deleting our browser cookies, adjusting our privacy settings or even unsubscribing from the service.

Algorithm Feedback

Jebara mentioned that a multitude of mixed-method machine learning algorithms are implemented to hone everything from predictive analytics and image curation to user-enforced restrictions and feedback mechanisms.

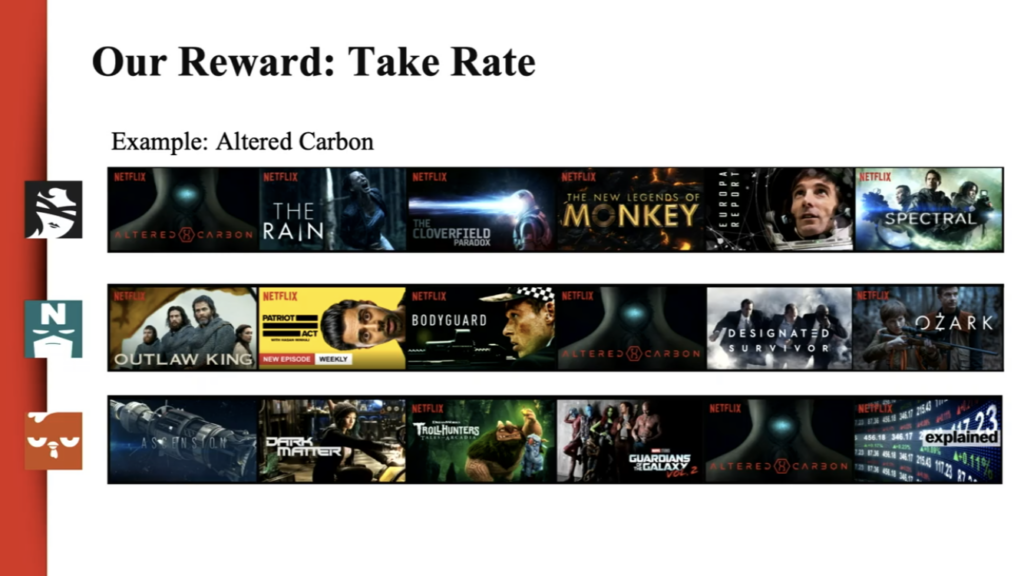

Jebara described their method take rate as a curatorial feedback strategy which tests different personalization experiences on several users to determine which of the content shown resulted in an actual viewing.

This strategy uniquely prefers the measurement of the number of viewers that strategy worked for over the number of viewers a specific piece of content was shown to. Jebara noted this method enables Netflix experts to learn from users by letting them show what content they prefer and in which ways they’re drawn to recommendations.

User Generated Feedback

This is a major shift from their previous user experience of providing users with the ability to ranking rank content using a star ranking system. Overtime and through observation, Netflix realized they couldn’t rely on that ranking system as a source of truth for which content users ranked highly versus which they’d prefer to watch. Jebara added users were not truthful in their telling of which content they preferred. Shifting away from user interaction to user observation has enabled a greater foundation for developing recommendation systems.

Conclusion

As content personalization algorithms advance, consumers will become a more passive actor in teaching content personalization algorithms. Every attempt at restricting interaction with such algorithms will lead only to yet another loophole identified by machine learning experts. How those companies manage those algorithms and exploit those loopholes are examples of the digital power dynamic which exists between the content generators and the content consumers.

References:

Berkowitz, Joe. “Is Netflix racially personalizing artwork for its titles?One writer’s experience with Netflix’s title art has us wondering whether the company is quietly using race in its algorithm for visually recommending films”. Fast Company (2018). https://www.fastcompany.com/90253578/is-netflix-racially-personalizing-artwork-for-its-titles

Castells, Manuel. The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. Wiley-Blackwell (2010). https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/876462/mod_resource/content/1/manuel_castells_the_rise_of_the_network_societybookfi-org.pdf

Chmielewski, Dawn C. “Netflix’s Use of Artwork Personalization Attracts Online Criticism”. Deadline (2018). https://deadline.com/2018/10/netflixs-artwork-personalization-attracts-online-criticism-1202487598/

McChesney, Robert W. Digital Disconnect. The New Press (2013): 63-171.

Wirth, Karl. “Netflix Has Adopted Machine Learning to Personalize Its Marketing Game at Scale: Here’s how you can humanize marketing strategies”. Entrepreneur (2018). https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/311931