In 2013 the Guggenheim hosted a James Turrell’s retrospective that transformed the iconic rotunda of the Guggenheim into Aten Reign, a large scale and site specific work using light, changing colors, air and space, and the curves of the museum itself. Turrell transformed the Guggenheim into a site for artful reflection for all who entered the space. Rather than an object to look at or a subject to contemplate, the experience of being in this transformed space was the work of art. “A lot of it is the idea of seeing yourself seeing, and how we perceive” Turrell has said of his work that lacks image, object, or “one place of focus” (Guggenheim).

During the length of this exhibition, there was no art on the walls of the Guggenheim’s spiraled hallway. Visitors were encouraged to lay on the ground of the lobby and gaze at the ceiling, which, using light and color, had been transformed into overlapping ovals of bright fluorescent hues. It was ethereal, magical, meditative, sublime. In an attempt to preserve the sense of bliss and encourage quiet, unmediated reflection, no photography was allowed in the space.

Something I can say with complete certainty is that hearing a security guard shout into an echoing rotunda “NO PHOTOGRAPHY” every two minutes was not conducive to an ethereal, magical, meditative, or sublime experience. Something I learned during my visit to the Guggenheim that day was that visitors will do whatever they want. They will get the validation of their experience that they expect. They will share their experience no matter what.

This experience, six years ago, has stuck with me and prompted me to think about how the relationship between people and their smartphones has affected the experience of viewing art in a museum gallery setting. This experience, among others, has largely influenced my interest in museum studies, digital media, and tech theory.

Background

I used to always bring a journal into a gallery and take notes on the works I liked, the artists, themes, books I should follow up with. Now I take photos of wall texts, books I want to look into, and of other people taking photos in the galleries. Sometimes I feel weary and critical of my own increased use of technology in galleries, but recognize that people, including myself, want to personalize, document, and share their experiences. In Finding Augusta, Cooley discusses Michel Foucault’s conception of “speaking the self,” and that often “much of what we document of ourselves transpires at the nonconscious level of the proto-self, at the level of impulse” (Cooley, 2014). This interest in “speaking the self” extends into many, if not all, facets of our digitally connected world.

Prompted by this assignment to conduct an observation relating to information studies and our personal interests, I decided to do an observation at the Museum of Modern Art. My intention was to observe specifically how people use technology, specifically smartphones, in a museum gallery setting.

Perspective, or, guiding questions for assignment

General questions to guide my inquiry:

- How do people engage with art in a museum gallery setting?

- How do people engage with technology in a museum gallery setting (both their own devices or provided by the museum)?

- How does technology, specifically the use of personal devices, mediate a viewer’s experience with art in a museum gallery setting?

- What do people do with their personal devices? Social media, digital scrapbooks, text messaging, etc?

- How does the use of technology by others affect an individuals experience in a museum gallery setting?

Specific questions for observations:

- How many people who walked through the gallery used a photo to take a photo of a work of art?

- How many people used their phone for non-art related purposes, namely, communication?

- What other phone use did people engage in?

- How many people used a camera to take a photo of a work of art or the gallery?

- What other technology was used (either personal devices or provided by museum)

Observations and data

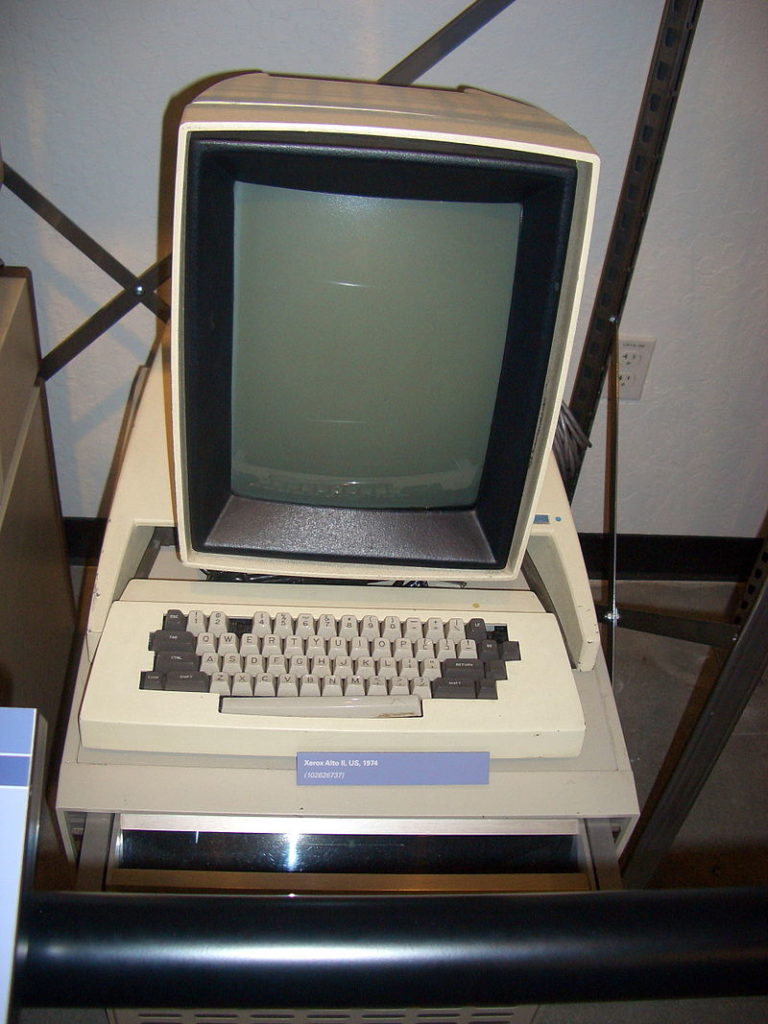

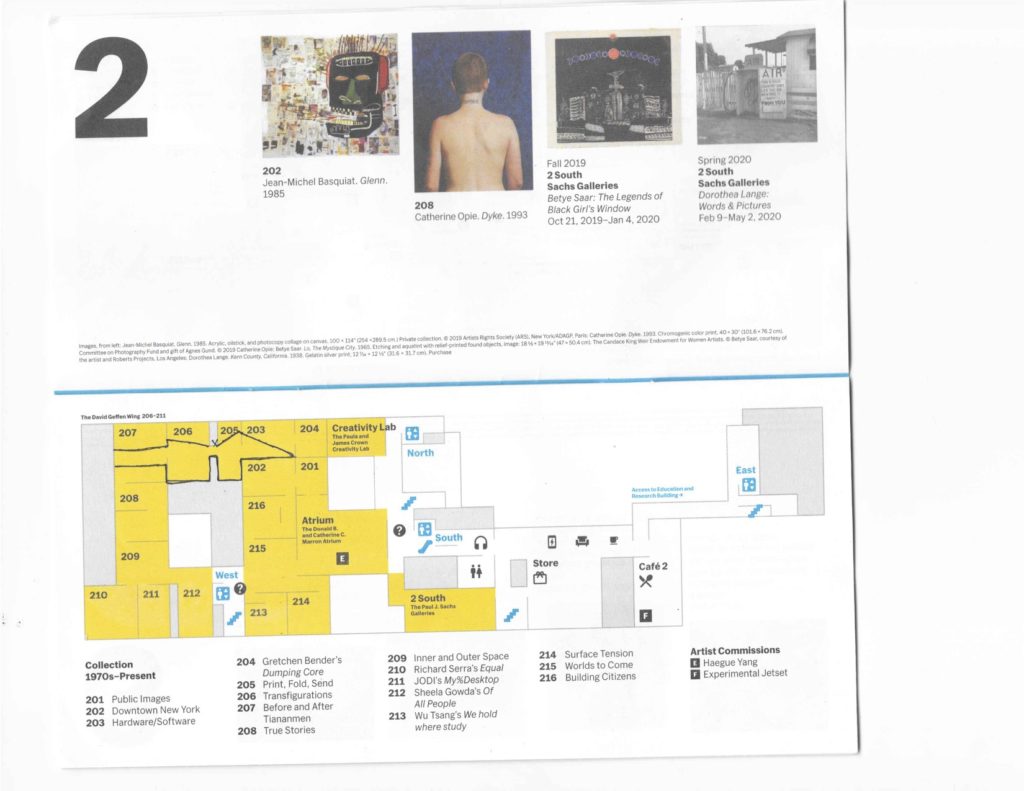

I sat between rooms 205 and 206 (marked on Fig 1) within an exhibition titled “1970’s-Present.” Immediately upon entering this exhibition space on the second floor of the museum, there were large paintings by Keith Haring, Jenny Holzer, and Basquiat. Further into the gallery I found a place to sit, where I could observe visitors walking through the gallery in either direction. My focus was on visitors who walked into room 205 and then through rooms 205 and 206.

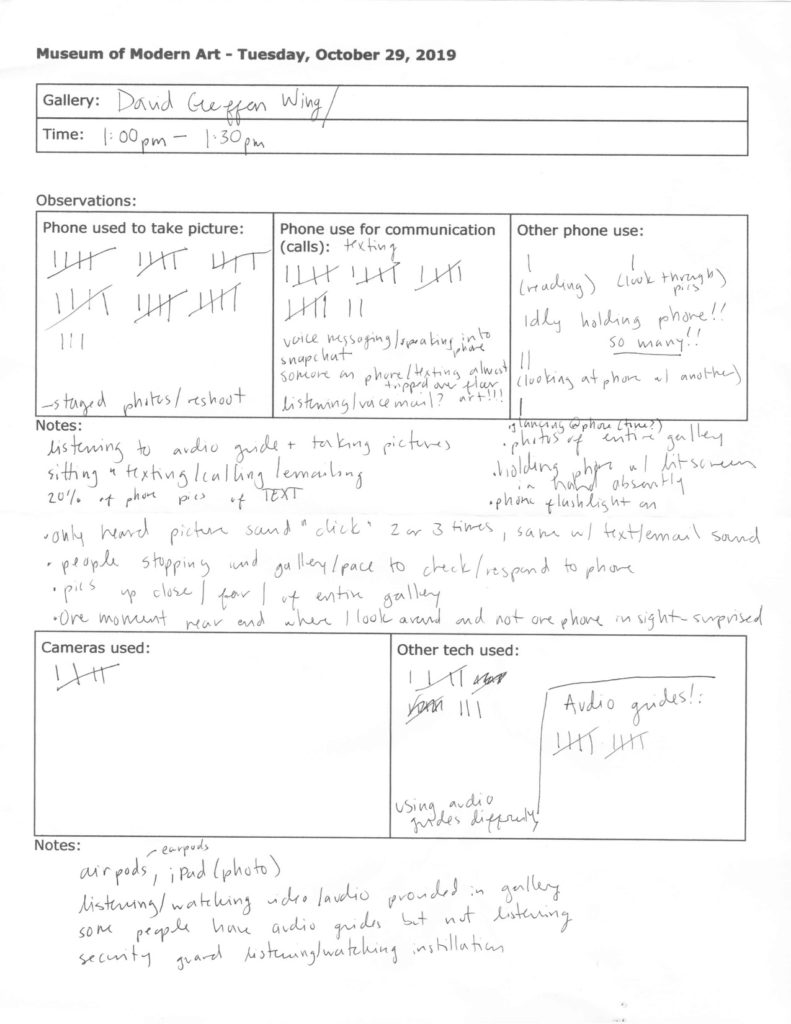

I used a worksheet to tally how people took photos of artwork in these gallery rooms with a smartphone, camera, or other device. Using a tally system I recorded how many people used their phone for communication (in some cases I couldn’t tell, in some cases I could see that people were texting, snapchatting, emailing, on Instagram, etc.). When I could, I recorded when people were using their phone for non communication or photographic purposes. The accuracy of these recordings were to the best of my observations as someone casually sitting on a bench in the gallery (I did not walk up to people or move to try to see anyone’s screens).

Breakdown of tally (from Fig 2):

| Phones used to take pictures | 33 |

| Phones used for communication | 22 |

| Other phone use | 5 |

| Cameras used to take photos | 5 |

| Other tech* seen *Airpods, iPads, earpods | 8 |

I realized while taking these observations that I did not include a section for audio guides. I added a section on my worksheet, but studying and observing audio guide use in the galleries could be an entirely separate set of observations and data that could easily include analytics from the devices.

A few things that stood out to me during these observations and while reflecting on the data:

- Within the scope of half an hour I had collected more data and notes than expected. I had intended to stay in the gallery for one hour but decided to end observing at half an hour.

- Almost as many visitors used their phones to communicate as take photos of the works, although visitors mostly used their phones to take photos.

- It was noticeable how many people idly held their phones in their hands. Rather than reaching for a phone from a pocket or bag to take a picture or send a text, the phone was constantly ready to be used.

This last phenomena of visitors constantly holding their phone also points directly to our class discussion around Steve Jobs saying of the iPhone that it “fits beautifully in the palm of your hand.” This also relates to Foucault’s conception of “speaking the self” mentioned earlier, where we, as visitors in a cultural institution, see something that we react to (either emotionally, aesthetically, personally, etc) and find ourselves compelled to document and/or share. By focusing on cell phone use within the space of the gallery, I was in a unique position to notice a seemingly small detail that could have interesting implications in understanding how people connect to their technology in a museum setting.

Further research

Further research may include doing similar observations near works of art that are of higher profile. Had there been a place to sit and observe unobtrusively, I may have chosen to sit in the room with the Haring, Holzer, and Basquiat works. Immediately upon entering the 1970’s-Present exhibition, visitors are confronted with large scale, recognizable, and graphically engaging works by artists that are more recognizable than in the rest of the gallery. I am confident that different observations would have been recorded in that space given those particular works of art.

Further research that would be fruitful would be to understand what visitors do with their photos after they’re taken. If asked, “what are you going to do with that photo you just took?” Answers could range from, “I want to post it to my Facebook page,” to “I want to save this memory,” to “I am sending it to my friend who loves this artist,” to “I am working on a research paper.” I am interested in what the actual responses would be and their frequency.

Conclusion

The conversation about technology in art and museum spaces is continuing to unfold as our lives and relationships become more and more mediated by technology. Much thought is being put into how museums and cultural institutions should relate to users and their lifestyles, many institutions have dramatically changed their photography policies in the past decade (Gilbert 2016), a direct result of the ubiquity of smartphones and visitors interest (and adamance) in documenting their experiences. As technology changes and evolves in ways that affect habits and our attachment to convenience and accessibility of social media, public institutions will need to grapple with how these developments affect their mission, rules, and expectations of visitors.

Works referenced

Cooley, Heidi Rae. Finding Augusta: Habits of Mobility and Governance in the Digital Era. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 2014.

Gilbert, Sophie. 2016. “Please Turn On Your Phone in the Museum.” The Atlantic. Accessed October 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/10/please-turn-on-your-phone-in-the-museum/497525/

“Introduction to James Turrell.” The Guggenheim Museum. Accessed October 2019. https://www.guggenheim.org/video/introduction-to-james-turrell