On April 13th, Saturday, ‘The Cherry-Blossom Festival’ was held at the Four Freedom Park at Roosevelt Island. The festival was organised to celebrate Roosevelt Island’s blooming cherry blossom trees and was also featuring traditional and modern Japanese performances and Cultural Fair.

The festival was free, and registration for the event was voluntary and was only there for organizers to estimate the number of people attending .

It was encouraged to take public transportation for the event as there is limited parking space available at Roosevelt Island. The modes of transport in and out of the island available were – subway, tram, ferry, bus and car.

The first sign of trouble which was visible while arriving to the island was that the waiting time to take the tram was no less than 2 hours. But at least the Subway and the Bus traffic was moving smoothly. Even after arriving the Island via the Subway, people were greeted with an extremely crowded subway station. But at this point all everybody desired was to escape the subway station and rush towards the necklace of cherry blossom trees present at the island.

While at the island, people enjoyed the beautiful displays and performances. The problems began when people started heading back home. The island had drawn such a crowd that all the modes of transport were jammed. The line to the subway station grew so long that the end of it was not visible. The bridge, tram, Subway, NYC Ferry, and bus service all experienced crowding and delays. The crowding got even severe after 1:45, when the NYPD briefly asked MTA to bypass the Roosevelt Island stop so that paralyzed F trains could move again.

This was the point where there was a sudden switch in the behavioral pattern of the attendees. It went from ‘relaxed, enjoying the beauty of spring’ to ‘Need to find means to get off the island at once’.

The surge of urgency and frustration seemed contagious. The people started gathering information to select the best possible mode to get off the Island.

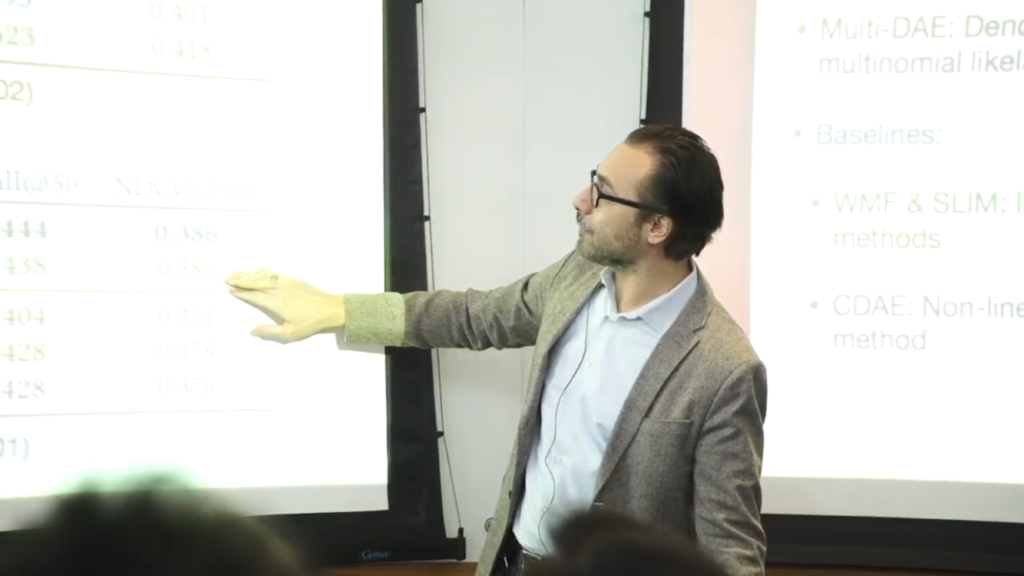

The characteristics that were witnessed in their behavior were closely related to the characteristics stated by Ellis in ‘ Wilson, “Human information behavior”’

which are:

Starting: the means employed by the user to begin seeking information, for example, asking some knowledgeable colleague.

Chaining: following footnotes and citations in known material or “forward” chaining from known items through citation indexes.

Browsing: “semi-directed or semi-structured searching;”

Differentiating: using known differences in information sources as a way of filtering the amount of information obtained.

Monitoring: keeping up-to-date or current awareness searching.

Extracting: selectively identifying relevant material in an information source.

Verifying: checking the accuracy of information.

Ending: which may be defined as “tying up loose ends” through a final search.

It started with people asking MTA staff or visible event organizers the best means (of transport) which might take the least possible time. When no substantial answer was given to them they started chaining which in this case might just be following directions given to them by fellow attendees of the festival, who might’ve been trying to leave since an hour earlier, thus, having more experience in that current scenario.

Then they started browsing the different options available for getting off the island. Differentiating them by an estimate of time it might take if they opt for each of the available options, or in what direction of the city it would take them. They kept monitoring the progress of the lines, whether they were moving, or the amount of people present in the lines for the Subway or the Bus.

People then extracted the data which seemed relevant to them, making decision, for example selecting to travel by bus, because the line seems the shortest and they would definitely get a seat when the bus arrives. But still kept verifying the time when the bus would arrive by messaging the number present with the details of the bus, which informed them of the estimate time of arrival and current distance of the bus from the stop.

But in the end they still kept a track of whether the subway line was moving faster, so they could switch the mode they selected according to their observations.

The search for any sort of information begins with the need to solve the problems being experienced by the users. During the festival, the attendees faced a problem and looked for methods in which they could solve the problem. Even though everyone unknowingly followed the simple basic method of narrowing down to their preferred mode of transport, the ultimate decisions taken and the reasoning behind those decisions were all distinct. The process incorporated a series of encounters with information within the space rather than a single incident from which a decision was made.

References:

- Wilson, “Human information behavior”. – Ellis, D. (1987). The derivation of a behavioural model for information retrieval system design. Information Studies. Sheffield, University of Sheffield.

http://inform.nu/Articles/Vol3/v3n2p49-56.pdf - Kuhlthau, Carol C.”Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective” “Journal of the American Society for Information Science’

https://ils.unc.edu/courses/2014_fall/inls151_003/Readings/Kuhlthau_Inside_Search_Process_1991.pdf - https://www.fdrfourfreedomspark.org/public-programs-events/2019/4/13/roosevelt-island-cherry-blossom-festival