On Friday, April 12th, I attended the Whitney Museum of Modern Art. The Whitney is an eight-floor contemporary art museum located in Manhattan, NY. Their focus is on presenting the full range of twentieth-century and contemporary art with emphasis on living artists. Aside from the exhibitions inside the museum, the building is beautifully designed. It is also located between the highline and the Hudson River. There is a view of the city or the river from any window or terrace. For the purpose of my observation, I was particularly interested on two artworks located on the sixth floor. These artworks seemed to be a combination of technology and art.

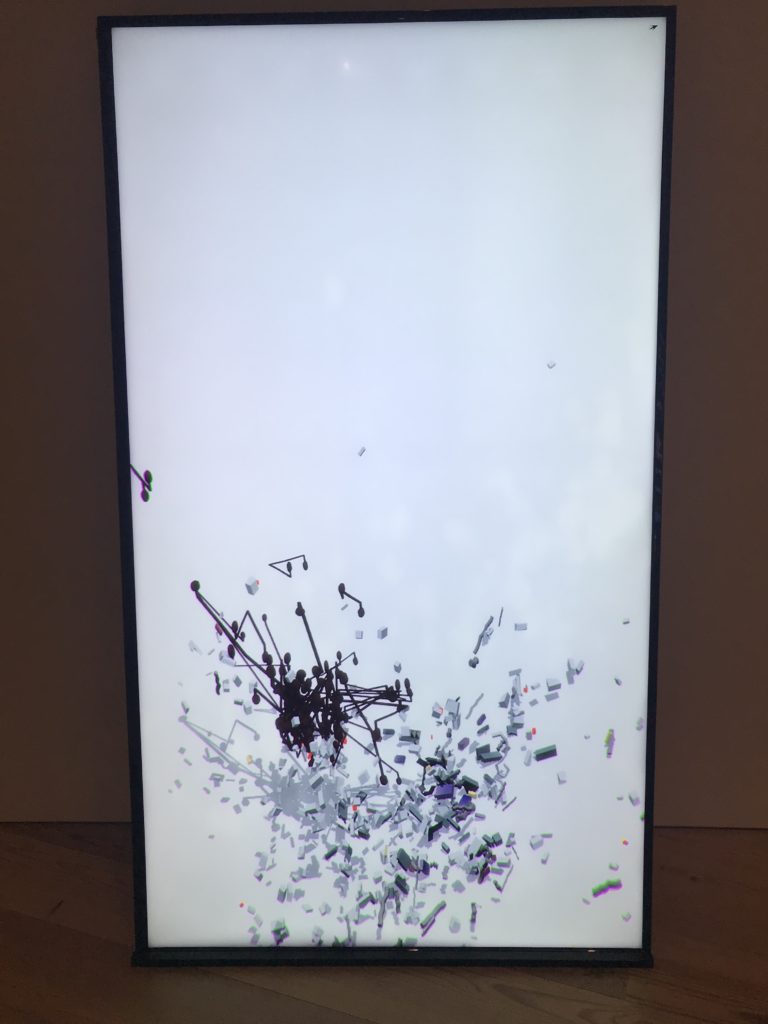

The first piece that I was found interesting was “Baby feat. Kiera” by Ian Cheng (See Fig. 1). In this piece, Cheng’s software enables audible conversation between three online chatbots whose voices then animate a swirl of debris. It does so by using Wi-Fi to query three different customize chatbots from different services to create the impression that they are “talking” to each other. The debris on the screen repeatedly coalesced and disintegrated, exhibits strange patterns on the screen. The chatbots are programmed to be “intelligent,” with basic learning abilities such as expanding their dialogue. However, because this piece queried responses from three different chatbots, the conversation was not cohesive. Instead, it was simply a series of words or sentences that did not have any particular flow. It was interesting to listen to some of thing that were said by these bots because sentences were incredibly complex.

In the article Fundamental Forms of Information, Marcia J. Bates provides a definition of information as being “all the patterns of organization of matter and energy,” which I thought was perfect for this piece due to the eccentric pattern of the debris as well as the incoherent conversation between the chatbots. This piece also prompted me to think of Don Norman and his idea of the human versus computers. In his essay, Being Analog, he says that “human languages still defies complete scientific understanding,” which I feel can be both supported and opposed by this piece. The chatbots in “Baby feat. Kiera” are programmed to be able respond to humans, learn from their responses, and expand their dialogue because of these responses. I feel that being able to learn from conversation is a humanistic element of conversation, which is emulated here. Moreover, the conversation that they are having is incoherent, representing a very non-human conversation. The visuals along with the audio represent artificial intelligence that is lifelike but also mechanistic, so I feel that the argument could go either way.

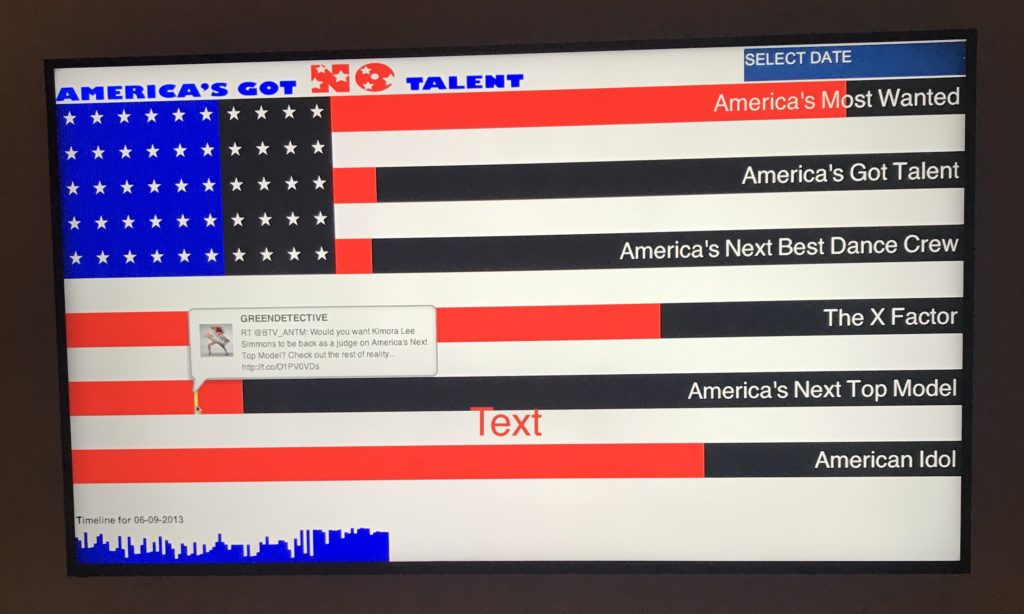

Another piece that I enjoyed was “America’s Got No Talent” by Jonah Brucker-Cohen and Katherine Moriwaki (See Fig. 2). This piece is a data visualization of Twitter feeds related to reality television shows such as American Idol, America’s got Talent, and America’s Best Dance Crew over a few years. The piece displays tweets that were sent and how much bias was gathered for each program based on retweets. By using horizontal bars in the shape of an American Flag, the visualization measures the success of TV shows linked to their social media presence. The artists for this piece successful connect the internet and the TV while clearly demonstrating the effect of a social media presence.

I feel that this piece was relevant to our conversation on big data and algorithmic culture. I am not entirely sure of the method or tools that were used to make this visualization, but I know that it needs a complex sequence of computational analyses. The tweets that are used in this piece could be defined as “big data” due to the fact that it was a such a large volume of data that was growing exponentially in a short amount of time (“What is Big Data and Why it matters).

There were several other pieces that incorporated technology as well but I choice to focus on “Baby feat. Kiera” and “America’s Got No Talent” because I found them most interesting. They were also the pieces that I spent the most time interacting with. I spent most of my observation simply observing and trying to understand the different patterns and conversations that were taking place in “Baby feat. Kiera.” I noticed that other museum attendees did not spend nearly as much time as I did with these pieces. Instead, it seems like attendees on this floor weren’t as interested in these pieces as they were pieces on other floors.

References:

Bates, M. J. (2006). Fundamental forms of information. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology,57(8), 1033-1045. doi:10.1002/asi.20369

Norman, D. (2008, November 07). Being Analog. Retrieved April 16, 2019, from https://jnd.org/being_analog/

What is Big Data and why it matters. (n.d.). Retrieved April 16, 2019, from https://www.sas.com/en_us/insights/big-data/what-is-big-data.html