At the top of the stairs, in a nondescript building in Manhattan’s upper west side lives a library; chronicling the history and differing manifestations of a school of thought critical to the development of computation and the algorithmic culture we live in today. The building is Prime Produce, an artist, educator, and community organizing co-op and the collection is The Cybernetics Library.

The “library” is perhaps best described as a “library of systems rather than a library of technology” says Sarah Hamerman, Project Cataloguing Specialist for Rare Books at Princeton University Libraries and Cybernetics Librarian. Through a physical and digital collection of books, zines, ephemera, articles, and guides the Library works to trace the history of cybernetics as a conceptual framework, unearth it’s influence on the history of computation and political organization, and make visitors and users aware that the questions we have today about how we might ethically and justly relate to each other, to non-human agencies, and deal with power in a mediated world are not new, but at the heart of the entangled history of society and technology in the broadest sense.

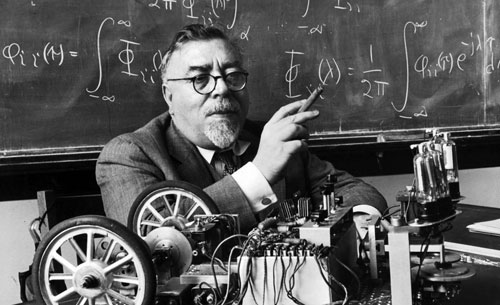

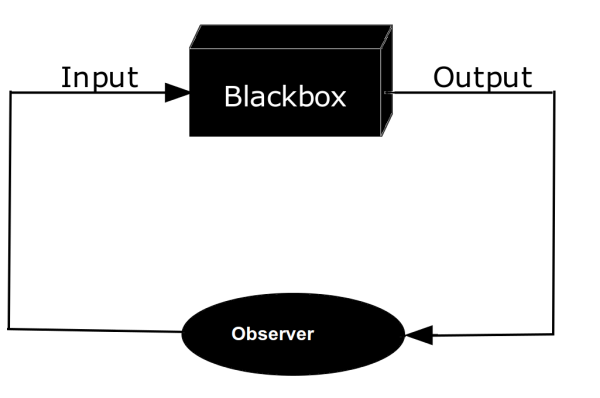

But what is cybernetics and why is it so important to computing? The word may sound familiar to anyone even adjacently related to computer science, information technologies or speculative fiction. “Cybernetics” is attributed to MIT mathematician, Norbert Weiner, who articulated this “new science” in his 1948 publication of the same name (Kline, 2015). Weiner defined cybernetics as the study of “systems of communication and control in the animal and machine”. Synthesizing research done and observations made by several scientists and scholars including Claude Shannon (who published his “Mathematical Theory of Information that same year), anthropologist, Margaret Mead and John von Neumann and largely focused on optimizing information sharing in relation to the war effort, cybernetics suggested that the mechanisms of feedback, or the movement of outputs and inputs within a complex system, that were being applied to the design of machines could be applied to mapping, understanding, and by extension, influencing biological life (human and non-human) as well (Kline, 2015).

Norbert Weiner, Cybernetics Library Image Collection

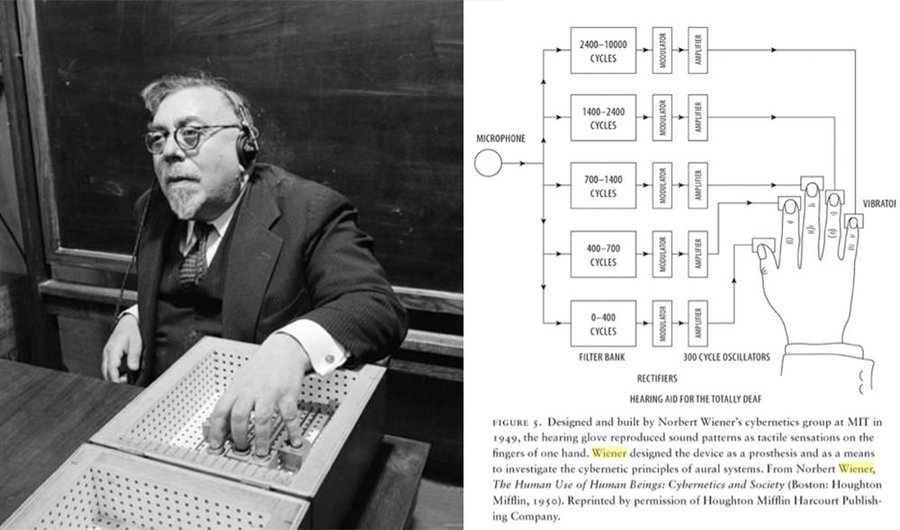

Norbert Weiner and Hearing Glove, Cybernetics Library Image Collection: Weiner applied cybernetics in his design for a hand worn apparatus that would translate the sound waves of human speech into vibration on the tips of the fingers

Looking at the history of Cybernetics is also looking at the history of the development of computation in service of military apparatus; charting a lineage of influences from Weiner and Shannon, to Jay Forrester and the development of the missile defense system during the Cold War and eventually to the ARPANET, whose development was commissioned and funded by DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) and would lead directly to the internet. But the use and application of cybernetics is complex and muti-faceted. When I asked Sarah to define Cybernetics she made sure to situate it’s birth within this military context while pointing to alternative interpretations that were also critical to the birth of Silicon Valley:

“Cybernetics is a kind of trans-disciplinary set of ideas that emerged in the 40s and 50s. It’s a way of looking at how social, technical and engineered systems operate and how mechanisms of feedback alter the functioning of the system…This set of theories was quite important in the early development of computation, which did come out of a military context. But then on the other side of things, this way of developing a dynamic and systemic approach to thinking about the flows of information, the flows of power, and the flows of energy within mechanical systems became interpreted within the social sphere as a way of looking at how society could be organized through mechanisms that were more dynamic, non-hierarchical, in-flux and potentially [more] egalitarian than the kind of very hierarchical systems of order that had operated until this 1960s growth of social consciousness in the West.

So on the one hand [Cybernetics] has been used by existing structures of power to kind of optimize systems and is often talked about in this more technocratic way; in terms of control. But then on this counter-cultural side [Cybernetics] was thought of as ways to engineer these more fluid and open and dynamic systems; ecologically, socially, politically, what have you.”

One example of the counter cultural history of cybernetics is in the influence of the Whole Earth Catalog, a counter culture magazine founded by Stewart Brand and published in California in the late 60s. As Sarah explained, “the magazine was very much a catalog of resources for building a “back to the land” communalist lifestyle detached from the urban capitalist social formations”. This proposed social ordering was widely distributed and influential with the mass migration of young Americans to communes in the 60s, but was imagined as connected to technology as it was to the “natural world”.

Whole Earth Catalog Cover, Cybernetics Library Image Collection

“All of the books, manuals and different resources for building stuff were positioned as tools through the rhetoric of Brand and the Whole Earth Catalog. The Whole Earth Catalog ended up being really inspiring to a lot of the initial founders of Silicon Valley companies and what has become the modern big tech industry. This logic of the tool you can see having this throughline from the counter-cultural usage of the WEC to the technocratic of the term tool.

Every kind of program, digital system or app is talked about by these designers and developers as a tool…the ultimate goal of technology is to be these tools to make getting access to information and goods easier for this imagined urban white male consumer and to make invisible the systems of energy and labor that go into the construction of these tools to smoothly optimize or facilitate this access to information.”

There is an easier relationship with something that is “just a tool”. The logic of “technology as tool” shifts responsibility for all possible outcomes (and avoiding them) to the user; it obscures and blocks interrogation of the various economic, social, and environmental agents and formations that go into the construction of said “tools”. We should think critically about the behaviors made possible by what is optimized for in a design and what is not. This perspective, the neutrality of the tool, flows into our contemporary moment where machine learning and other forms of algorithmic decision making are positioned as inherently unbiased because they are technological constructs and are therefore objective. Further, as danah boyd and Kate Crawford speak to in “Critical Questions for Big Data”, the supposed objectivity of the big data paradigm obscures the messiness at every level of the process from procedures of collection to interpretation.

“I think as a group, as the Library, we want to make visible the real political complexity of what cybernetics is and how the use of this method of thinking can go wrong, while also thinking about how we can consider it as a methodology to be more aware of our social environment and to build these not necessarily technical but, also, social tools of inclusion.”

This complexity Sarah was speaking to starts in interrogating the lineage of cybernetics. Norbert Weiner to Sillicon valley is one story of this. But this narrative nests within the mythology the development of personal computing as a group of ruggedly individual geniuses tinkering in the proto-maker spaces of their home garages. But if we understand cybernetics as a way of thinking about how and where phenomena, human or otherwise link and are linked to one another, relate and are related to one another and move between and are moved between one another then cybernetic thinking existed long before personal computing, or post-war information theory knowledge , or human ways of knowing at all.

We might look at Project Cybersyn; a proposal for a computer system that would be used to manage newly nationalized industries in 1970s Chile is part of this cybernetic lineage. The fungal networks of mycelium (the root networks of fungi) that weave throughout the roots of trees in forests moving food and chemical signals (read: information) between individuals and colloquially referred to by biologists as “the internet of trees” are cybernetics. Patricia Hill-Collins’s articulation of the matrix of domination through which benefits and harms are distributed throughout populations based on race, class, gender, ability and many other constructed identities is also a type of cybernetics. Justice facilitator and community organizer, Adrienne Maree Browne’s articulation of an “emergent strategy for building complex webs of care and change that scale the transformations social movements work towards”, highly inspired by the work of Detroit based community organizers Grace Lee Boggs and James Boggs is a also a type of cybernetics (Brown, 2017). The usefulness of this thinking as a framework is not in translating various phenomena into “cybernetic manifestations”, but as a lens through which we might look at the relatedness of systems of knowing, sharing, being, and making on their own terms.

“As far as technology goes, I think that [the Library] as a group like to think of technologies as things that aren’t necessarily computational or aren’t necessarily engineered or mechanical systems. Different social protocols or ways of passing on information from person to person, sharing food, or constructing rituals can also be technologies that have a very important social function; allowing communities to survive and thrive or allowing relations to be measured in some way.

Framing technology as something that operates beyond the logic of the computational is a way for me of bringing in practices that are developed by women, communities of color, or Indigenous communities as always already technological or giving value to practices that operate outside these very strict Western Patriarchal logic of technology”

Inspired by the non-hierarchical and decentralized nature of cybernetics, the library is run not as a formal organization but as a collective. As Sarah describes, “Everyone contributes based on their abilities and availabilities and interests and skills for each project”. Where the six primary members (Charles Eppley, Sarah Hamerman, Sam Hart, David Hecht, Melanie Hoff, Dan Taeyoung) work together with a network of collaborators to organize the books and creating searchable records using LibraryThing. The books are almost all donations from private collections, or donated works from fans, scholars, users, and collaborators. Though Sarah notes that additions are also bought by the group, particularly to expand the voices and practices represented within the collection.

While the physical library is browsible primarily by request, engagement can take many forms, as Sarah describes: “Our activities are centered around pop-up libraries and workshops that either interface with other organizations and the public in certain ways or draw out specific themes of the library in different ways”. Past activities include the Cybernetics Conference (for which the collection originally began) and building a selection of titles investigating the cybernetics of sex for a workshop at the School for Poetic Computation, where faculty member (and cybernetics library co-founder, Melanie Hoff) was investigating gender, sexuality, the body and embodiment beyond the human.

Cybernetics, at least in the ways the Library would like users and visitors to think of it, asks us to consider the questions we have about technology today, the worlds we build with and through it are not new, but the newest iteration of our struggles around how we relate to each other, how we relate to the world, how power operates, and how we might reshuffle the pieces of a system to move us toward radical new ends. It’s a potentially critical framework for learning to live in a world where those with the privilege of being technology creators increasingly optimize for (read: shape and influence, explicitly and implicitly) particular formations of community and society. On the one hand we must look at the history of technology and computing as one directly connected to state driven innovations meant to intercede in feedback and shape systems towards militaristic and commercial ends. The Cybernetics Library would like us to consider what other networks we can and have built.

In light of this drive there’s an alternative story we can tell to the one that opened this article. In an artist/organizer co-op on Manhattan’s upper west side live a Library. But the library doesn’t only live there. It’s integrally linked to a community of users around the world, to the work of thinkers, artists, activists, and beings (human and otherwise). Talking to one another and working in around “technology”, whether that manifests in human or non-human agencies, digitally or analog. Wherever communication exists or becomes noise (which itself also communicates), wherever we might consider relationships of power, wherever we are thinking about how coalition and community are formed and maintained, cybernetic phenomena are happening.

As Sarah described at the end of our interview, “I want people to walk away from this collection considering how communities can work together to build systems and technologies that are rooted in an ethic of solidarity and care and that are developed to think more expansively and outside of capitalist solutionist logic of the things that technologies can do. I think that we can begin to imagine differently, informed by how technologies have been implemented already.”

Works Cited:

Brown, A. M. (2017). Emergent strategy: Shaping change, changing worlds. Chico, CA : AK Press,.