On October 19, 2019 I attended the Black Portraiture[s] V: Memory and the Archive, Past. Present. Future. Conference hosted by New York University. I attended two panel discussions. The first panel I attended was entitled: Archival Noise: Black Women, Sonic Remains and Afterlives in Transatlantic Slavery Archives. There were four presenters who each contributed to the panel by discussing how literature, sound, and various other forms of artistry conveyed the harsh realities of black women during and after the transatlantic slave trade. The panel discussion was compelling, but I found there was a notable absence of the role of archives in their research. Only one panelist, I. Augustus Durham in his presentation on “I Love “Lucy” I Think?: The Makings of Kendrick Dinkinesh” made mention of “the archive”, but only in passing when he said: “the artist’s (team of creatives) had a deep sense of “the archive”. (Durham, 2019). His statement was referencing the symbolism used to create an artistic piece by the hip hop artist Kendrick Lamar. He did not mention which archival records he was referring to, nor did he mention what archival analysis was utilized to arrive at such a conclusion. As this was a panel of humanities scholars, this led me to believe there was a distinction being made between the “archive” and “the archives”, and I was immediately reminded of the misconception commonly held in humanities studies about “the archive”, and archival studies.

Michelle Caswell who is a writer, scholar, and archivist writes: “For humanities scholars, “the archive” denotes a hypothetical wonderland…” (Caswell, 1). This was implied in Durham’s statement in reference to the archive. She goes on to state that there are two separate discussions taking place between archival studies scholars and Humanities Scholars:

“the archive” by humanities scholars and (of) archives by archival studies scholars are happening on two separate tracks in which scholars in both disciplines are largely not taking part in the same conversations, not speaking the same conceptual languages and not benefiting from each other’s insights” (Caswell 1-2).

It was very compelling to see this disconnect between the two disciplines actually taking place in academic discourse.

These separate tracks became even more evident during the second panel discussion of the day called: “New Media, Techno, Archive, and Art. Speakers on this panel discussed AI (Artificial Intelligence), big data, new media art, and addressed the biases embedded within these technologies. The panelist I would like to highlight is Dorothy Berry who is an Archivist at Houghton Library at Harvard University. Her presentation was entitled: “Archives in the Age of Digital Reproduction: Towards Discoverable Blackness. In her presentation she discussed the importance of Provenance in archival study and ways it could be applied in archival preservation of the historical records of African Americans. She stressed the importance of context in analyzing these archival records and the need for more collective description. She then went on to discuss the embedded racism found in the Library of Congress subject headings, and why patrons of color can be more active pointing out these things for modification (Berry, 2019).

While listening to Berry I was again reminded of the power archivists have in shaping memory. When dealing with marginalized communities whose histories and experiences have been largely misrepresented, applying provenance, and cultivating proper context in archival preservation becomes an even more daunting task:

“The nature of the resulting “archive” thus has serious consequences for administrative accountability, citizen rights, collective memory, and historical knowledge, all of which are shaped – tacitly, subtly, sometimes unconsciously, yet profoundly – by the naturalized, largely invisible, and rarely questioned power of archives (Swartz & Cook, 4).

Berry’s presentation demonstrated the influence archivists have in shaping collective memory. Berry also was able to convey the role racism plays (whether intentional or not) in affecting how African American archival records are archived. Berry’s presentation touched on issues of diversity emphasizing in her talk that 89 percent of archivists are white . She emphasized there was much need for community engagement (Berry, 2019). In The Quest For Diversity in Library Staffing: From Awareness to Action, Jennifer Vinopal using the ALA’s 2007 Diversity Counts Report states: “…a vicious cycle that the lack of diversity perpetuates: “[T]he lack of diversity in regards to race and ethnicity, age group, disability, and other dimensions…work [sic]to distance the very communities they seek to attract” (Vinopal, 2013). This “vicious cycle” is reinforced by Berry’s call for more participation from people of color in bringing awareness to biases within the archives, specifically in the archival preservation of African American Culture. There is a sentiment within the African American Community due to the forms of racism endured such as Jim Crow, that has led African Americans to internalize the belief that they are not welcome in certain spaces. I see this sentimentality being played out here, in reference to the lack of participation from the African American community, even in the reframing of African American culture through the archives.

As I mentioned earlier, I attended two panels each panel was very informative, and was very different from one another. The theme of the conference was memory and archive through the lens of the black experience. The topics of discussion were about how these concepts intersect and how we can better understand, work through, and work with the power structures that govern our society in the United States and abroad. Also, how marginalized groups can empower themselves with the use of modern technology to create, preserve, and reframe culture. As the technological age continues to advance rapidly, we are continuously challenged to find ways to adapt. Issues of privacy, racism, inclusivity, cultural preservation, and transparency are more important than ever. These topics will continue to be of great concern as we continue to move forward. Through these panel discussions I was able to begin to identify themes from course discussions, and see how they manifest themselves through academic discourse.

Works cited:

Berry, D. (2019, October). Archives in the Age of Digital Reproduction: Towards discoverable blackness. Paper presented at the Black Portraiture[s] V Memory and the Archive Past. present. Future. NewYork University. New York, NY

Durham, A. I. (2019, October) I love “lucy’, I think?: The makings of kendrick dinkinesh. Paper presented at the Black Portraiture[s] V Memory and the Archive Past. Present. Future. New York University. New York, NY.

Caswell, M. (2016) “The Archive” is not the archives: Acknowledging the intellectual contributions of archival studies. Reconstruction: Studies in contemporary culture 16(1). Retrieved from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bn4v1fk

Vinopal, J. (2013, January, 13). The quest for diversity in library staffing: From awareness to action. In the Library with a Lead Pipe Retrieved from: http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2016/quest-for-diversity

Schwartz, J.M., Cook,T. (2002). Archives, records, and power: The making of modern memory. Archival Science, 2 , 1-19, Retrieved from: https://www.nyu.edu/classes/bkg/methods/schwartz.pdf

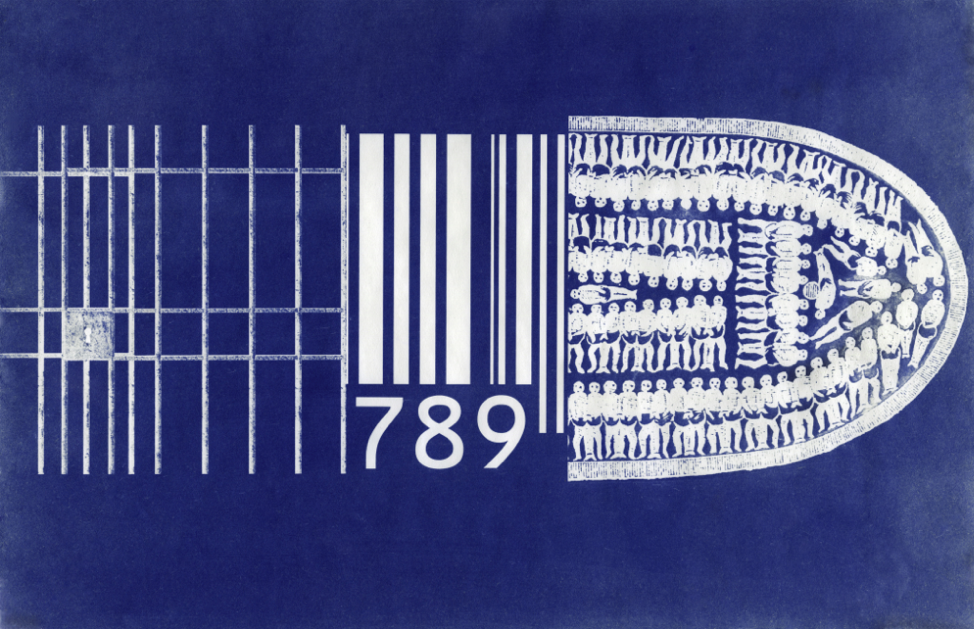

Illustration: Boddie, T. (2018) Prison Industrial.