Taylor Norton Event Attendance

For my event attendance, I went to the Museum of Interesting Things’ Monthly Speakeasy. Held in a loft in Soho, I was one of approximately 40 people in attendance. The museum is described on its site as “a traveling interactive demonstration/exhibition of antiques and inventions inspiring innovation and creativity – learning from the past to invent a better future.” For this night, whose theme was “I Spy: Spy, Cipher, Crime, and Communication Tech,” the museum was held in a loft in order for attendees to not only handle and interact with objects, such as an enigma rotor, a pair of hoodwink goggles, watch cameras used by detectives, 16 mm films, and an encoding machine paired with a carrier pigeon vest, but also to eat, drink, and meet others also interested in the same topic. People in attendance could look at 20thcentury mug shots hanging on the wall and flip them over to read the crimes committed while others could take selfies while wearing the hoodwink goggles.

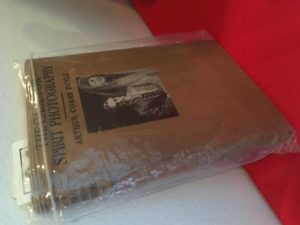

Initially, the most striking thing to me was how poorly preserved and displayed many of the items were. Old ephemera, mug shots, books, and technology were housed in plastic Ziploc bags while some photos were displayed in an envelope with a transparent windowpane. Other objects were simply placed on the table with no protection at all as people leaned over precariously with a full glass of red wine in their hand. Also, none of the items had labels for a viewer to properly identify them. However, I soon realized this was only minimally problematic as I witnessed the night’s host and the museum’s owner, Denny Daniel, explain every item in detail to whoever took an extended period of time looking at an object. He saw the explanation of each object as an opportunity to connect with others and engaged with everyone who was there. After talking with Daniel, I also found out that when the items are not being displayed at travelling shows and educational events, he stores them in his home and four storage units around the city. I could not help but think of how most preservationists would lament at the rate of deterioration from such handling and the lack of a controlled environment. While considering this dilemma, a quote from Roy Rosenzweig’s article, “Scarcity or Abundance? Preserving the Past in a Digital Era” resonated with me. While Rosenzweig refers to preservation in a digital era when he writes about “who has the right and responsibility to preserve them [materials],” (Rosenzweig paragraph 16) I found that the same notion could be applied to physical objects without a digital presence as well. The idea of responsibility and ownership of the past’s object has always been assumed to be that of museums, historians, catalogers, and archivists but here was a single person preserving and showcasing items.

With that being said, I actually believe that more people should host events like the one I attended. While most professionals would have dismissed Daniel’s attempts at sharing his antiques as unsustainable and minimally factual, he had an audience who was diverse in age, gender, and race that was fully engaged in their environment and eager to learn about the objects at hand—literally. They were closely examining objects, questioning how others used the items, and critiquing the creative techniques used in the creation of WWII propaganda 16mm films. Should that not be a main goal of a museum and/or a collection? And while there was a lack of what most would define as professionalism that a larger institution would have, his museum was still serving the same purpose of transferring knowledge and understanding of the past and past narratives.

This museum is clearly a passion project, which is reinforced when reading Daniel’s call to action on his brochure that “Maybe we can think of ways to use yesterday’s technology to power the future.” And while it was a small event, his passion could have easily been harnessed and sponsored by a larger entity that could have displayed things in a neater and more professional matter and reached a larger audience. However, I say that hesitantly because I also recognize that the larger the institution, the more control over objects is inherently introduced. Daniel explains that “the beauty of our programs is that they can be tailored to the interests or curriculum of any range of age groups from Kindergarten-high school, spec. edu, college, adults and seniors. Moreover, our programs can be presented in almost any type of venue- large or small and indoors or outdoors.” While many would dismiss Daniels collection as merely that of an enthusiast, what Daniels is actually doing is vital because he is making information not only accessible but also interesting to a vast array of the general public.

It was my own bias to Daniel’s museum that made me reaffirm how important it is to recognize how things are presented and by whom. Had his enigma rotor been showcased in London’s Imperial War Museum, I am sure nobody would have thought twice about its efficacy. However, because it was placed on a foldout card table, its initial presence was questioned. While thinking about how I momentarily did not want to take Daniel’s collection seriously because it lacked the traditional standards of storing and showcasing items, a quote from Joan M. Schwartz and Terry Cook’s article, “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory,” came to mind: “In the design of record-keeping systems, in the appraisal and selection of a tiny fragment of all possible records to enter the archive, in approaches to subsequent and ever-changing description and preservation of the archive, and in its patterns of communication and use, archivists continually reshape, reinterpret, and reinvent the archive. This represents enormous power over memory and identity, over the fundamental ways in which society seeks evidence of what its core values are and have been, where it has come from, and where it is going. Archives, then, are not passive storehouses of old stuff, but active sites where social power is negotiated, contested, confirmed” (Schwartz 1). While I know Daniel’s collection is not an archive, it shares the same parallels of power and how it can be presented and reinforced. The past use and importance of the items he had did not change by themselves, but rather by the context in which they were viewed.

Rosenzweig, Roy. (2003). “Scarcity or abundance? Preserving the past in a digital era,” The American Historical Review 108(3): 735-763. http://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory/links/pdf/introduction/0.6b.pdf

Schwartz, Joan M. & Terry Cook. (2002). “Archives, records, and power: the making of modern memory,” Archival Science 2: 1–19.