When does a book become a danger to itself? Franklin Furnace Archive deals with this question on a regular basis. Their growing archive consists of artists’ books that are made from a plethora of materials and take on many forms – making preservation difficult. On October 23rd I attended the Archive’s open house to see for myself what these “books” look like and how they are stored.

The head archivist, Michael Katchen, opened with a brief history of the archive. Franklin Furnace Archive was founded by Martha Wilson in 1976, focusing on the collection of artists’ books and performances. In 1993, MoMA acquired their collection – contingent on certain terms, and in 1997 they transformed from a “physical exhibition space into an Internet-based one”1. In 2014, the archive moved to its current home on the 2nd floor of the former building of Pratt’s School of Information.

The terms agreed upon in this 1993 acquisition are incredibly interesting: whatever books are accepted into the Franklin Furnace in the future have to be accepted into MoMA’s archives as well,becoming part of their permanent collection. So, what are the criteria for a book to be accepted? Michael says that as long as the artist believes that what they are submitting is a book, then it is so. This means that I could submit two copies of a work, in any form whatsoever, and finally get my work into MoMA.2

Michael went on to explain technical details about the archive; how items are preserved, and how items are accessed. The nature of the collection means preservation is challenging. Books in the collection may not resemble books at all, and their materials can degrade easily. Books that fit into certain dimensions are kept in phase box enclosures, others are kept in whatever containers they were sent in. An example of a more unorthodox enclosure were two “books” that Michael accepted into the archive last year. He walked over to a shelf and pulled down two plastic white paint buckets, opened them, and removed two paint-dipped tomes. They were more form than text, and totally unreadable, but they push what the boundaries of what an artists’ book can be.

Many of the older books and book forms have accompanying video documentation from related performances by artists, which are accessible through their online event archives3. The physical items from the early days of the archive have time-based media documentation attached to them. To preserve those films, Franklin Furnace has a digitizing workstation to produce preservation copies and DVD’s.

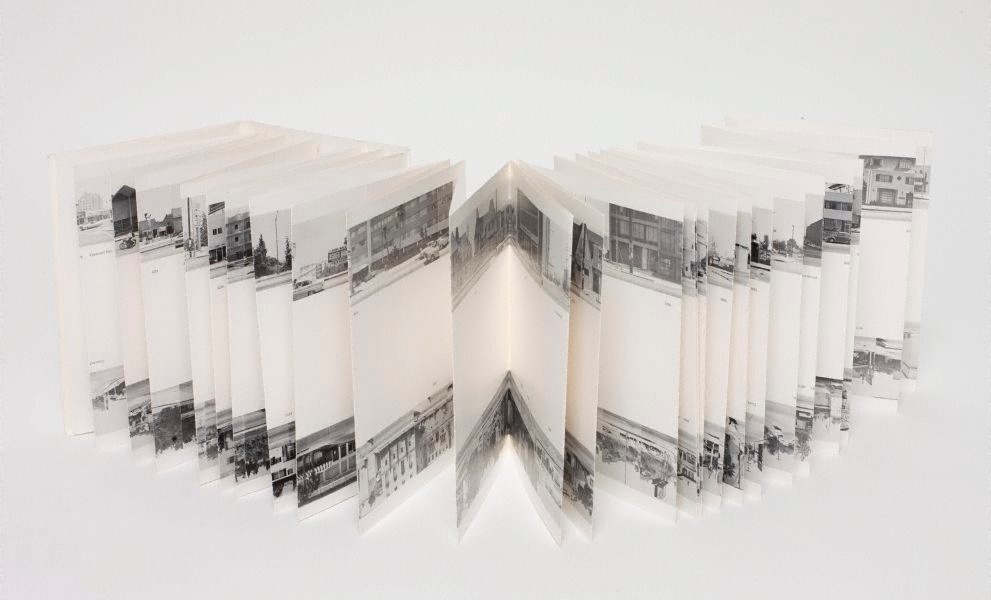

Edward Ruscha, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1966

Anyone can go to the archive and experience the books. The only requirement: a clean set of hands, and the whole archive is at your disposal. I was able to touch and flip through Ed Ruscha’s original 1966 work, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, which is a 25-foot long accordion-folded book. Michael’s estimate of the work: around $20,000 or so. It was an empowering experience to be in such close contact with the works at Franklin Furnace, and I appreciated how much access they grant to the public.

1Franklin Furnace. “History & Collections.” Accessed October 25, 2017. http://http://franklinfurnace.org/research/index.php

2“Franklin Furnace Artists’ Books Collection.” Accessed October 25, 2017. http://franklinfurnace.org/research/moma-FF-artist_book_collection.php.

3Franklin Furnace. “Event Archives.” Accessed October 26, 2017. http://franklinfurnace.org/online_event_archives/index.php.