by Blair Talbot, Claudia Berger, Jiyoung Lee,

Kelli Hayes, Mickey Dennis, and Chris Alen Sula

There are several tellings of the story of Turtle Island, the name that many Indigenous peoples, especially Algonquian- and Iroquoian-speaking peoples, use to describe the creation of their land. Some Ojibwe people say that the Creator sent a flood to cleanse the world after people strayed from peace by warring with each other. Only one person and a few animals survived the flood. They attempted to recreate the world by collecting soil from deep below the water. All of them failed except the muskrat, who returned with soil but perished from the effort. A turtle agreed to bear the burden of the soil on its back, and the land grew into what is known today as North America.1

In geologic time, the land that makes up North America has collided and broken apart many times. Parts of the continent separated from the supercontinent Pangea around 300 million years ago, drifting and crashing into each other over hundreds of millions of years. By 65 million years ago, the continent took on its modern outlines. Glaciers advanced onto what is now known as New York between 90,000 to 22,000 years ago, reforming the landscape, exposing the bedrock, and depositing sediment and debris. When the last glacier retreated around 18,000 years ago and the Ice Age ended about 10,000 years ago, plant and animal life rapidly changed and their numbers grew. Sea levels and environmental changes stabilized about 6,000 years ago, bringing about the current geological era and allowing the original caretakers of this land to flourish.

For more than 10,000 years, the Lenape people have cared for land on which our institution now sits and on which most of our project work has occurred. Lenapehoking, the land of the Lenape people, spans from Western Connecticut to Eastern Pennsylvania, and the Hudson Valley to Delaware, with Manhattan at its center. Over the past 400 years, acts of genocide, forced displacement, and systemic oppression have dispersed the Lenape people throughout the U.S. and Canada.

From the earliest formulations of this project about plants, we knew that settler colonialism—understood to include “spatial removal, mass killings, and biocultural assimilation” (Wolfe, 2006: 409)—would be an important lens for this work, particularly as a group of non-Native graduate students and faculty, most of whom were born and raised on occupied land in the United States.2 As our research progressed, we recentered our thinking around Indigenous peoples, their uses of plants, and possibilities for imagining alternatives to the landscapes we see today—in line with Kauanui’s call to place Indigenous studies alongside discussions of settler colonialism (2016). This led us to engage the Lenape Center and its co-founder and co-director Curtis Zuniga, cultural director for the Delaware Tribe of Indians, who spoke to us about Lenape history, culture, and relationship to the environment, which we discuss below.

We locate this project within the digital humanities and environmental humanities, two fields that share interests in critical thinking, public engagement, and collaborative models of scholarship (Sinclair & Poplawski, 2018). While the digital humanities has been keen to adopt various technologies for scholarly purposes, many in the field have called for more critical attention to the histories, embedded logics, and environmental impact of those technologies (Liu, 2012; Gabrys, 2013, Sinclair & Poplawski, 2018) as well as differential access to such resources across the globe (Gil & Ortega, 2016). Similarly, Rose and van Dooren (2012) describe the environmental humanities as “a difficult space of simultaneous critique and action,” poised between the desire to respond to pressing environmental concerns and the time required for slow, careful thought. This project inhabits a similar space; while we make frequent use of technologies in this project, we also seek to raise critical questions about those technologies, especially the colonial logics that mapping techniques embody. This approach aligns with DeLoughrey, Didur, and Carrigan’s (2015) call to “situate…environmental humanities with a firm grounding in the significance of the ongoing histories of imperialism” and with the seven principles of data feminism as described by D’Ignazio and Klein (2020).

Accordingly, we begin with discussions of context and methodology that inform our work with technology, examining and challenging the power structures and classification systems we encountered, embracing local Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, displaying the work and labor that went into our products, and concluding by noting limitations of our own work and provocations for the future.

Context

Work on this project took place as part of a graduate course, the second in a sequence following an introductory survey of digital humanities, its methods, tools, and impacts. Students and faculty worked together as co-researchers on this project, following principles set forth in UCLA’s Student Collaborators’ Bill of Rights. The course is situated in an iSchool, which focuses on relationships between information, people, and technology. In particular, we began with attention to the human impulse to classify knowledge through naming and taxonomies. The history of libraries, databases, data collection, and other information is heavily indebted to, and burdened by, Linnaean botany, where we begin our consideration of plants.

The Plant Kingdom / Linguistic Imperialism

There now, look at that: I am meaning to show how I came to seek the garden in corners of the world far away from where I make one, and I have got lost in thickets of words. It was after I started to put seeds in the ground and noticed that sometimes nothing happened that I reached for a book.

Kincaid, 2020, p. 26

Carl von Linné (commonly known as Carl Linnaeus, as he renamed himself in Latin) was an eighteenth-century Swedish botanist and physician who is often unironically regaled as the “father of taxonomy.” In Systema Naturae (1735), he developed his method of binomial taxonomic nomenclature, the classification schema for plants and animals still used today. The project of fitting the global natural world into a tightly ordered system of categorizing and naming individual species in the learned language of the European elite is faulty for many reasons: the erasure of local herbalist practices and autobotanical histories, the perpetuation of the idea that plant species are stable and static objects that are able to be defined as discrete entities divorced from their cultural and ecological contexts, and the fact that the obsessive taxonimization of the natural world is the prelude to extractive capitalism.

In 1623, about 6,000 known plant species were recorded by Caspar Bauhin. By 1800, over 50,000 had been catalogued by Georges Cuvier (Schiebinger, 2004, p. 194). The late modern period witnessed an explosion of interest in cataloguing the natural world: alongside the expansion of imperial power, a frenzied attempt to gather the plants across the globe and prune them into a newly invented taxonomic nomenclature took place. The coupled aims of Empire and the empirical sciences characteristic of this period crystallize in the language of a “plant kingdom.” This phrase is reflective of the tendency amongst European naturalists of this period to collect “the stuff of nature” and “lay their own peculiar grid of reason over [it] so that nomenclatures and taxonomies…often also served as ‘tools of empire’” (2004, p. 11).

Representations of the natural world are always a reduction of the polyphonic biodiversity that precedes language. That said, some degree of simplification is inherent in the tasks of description and communication. The late-modern natural sciences, however, undertook the task of exchanging diversity for taxonomy with such zeal that they thoroughly distorted their vision of nature. Botany, like other natural sciences, “began as a technoscope—a way to visualize at-a-distance—but, at the end of the eighteenth century, it was already a teletechnique—a way to act at-a-distance,” (Lafuente & Valverde, 2016, p. 140). Through scientific illustrations, nomenclature, and schema, early botany establishes a form of biopower and the network through which these knowledge objects circulate.

Fundamental to this burgeoning information communication network was the establishment of an international network of botanical gardens (Crosby, 1972, 1986; Brockway, 1979; Schiebinger, 2004, 2016). By the end of the late eighteenth century, Europeans had established 1,600 botanical gardens throughout the world along the tentacular contours of imperial expansion. These were not, as Schiebinger notes, “idyllic bits of green intended to delight city dwellers, but experimental stations for agriculture and way stations for plant acclimatization for domestic and global trade, rare medicaments, and cash crops” (2004, p. 11). Botanical gardens are uniquely situated within the history of plants and colonialism as both repositories of plant data and institutional sites of homogenization. European botanical gardens played a critical role in the colonization of the Americas and the extractive capitalism fundamental to this enterprise. Botanical gardens function on the forced removal of plants and knowledge from their local contexts for economic and strategic gain. British botanical gardens were particularly invested in the business of “convert[ing] knowledge into profit and power” through the exploitation of local knowledge, labor, and natural resources (Brockway, 1979, p. 192).

While mid-twentieth century historians have frequently operated on the assumption that scientific knowledge—which produces and justifies power—moves unilaterally outward from the center to the periphery, more recent historians of science have operated on the understanding that power is diffuse and that the production of knowledge occurs through movement along and in between the multidirectional vectors of information communication. Along with this historiographical development there has been a turn away from simplistic histories of colonial science that diametrically position the epistemological worlds of the colonizer and the colonized. The aim of this project is to bear this complexity in mind while taking a closer look at how the displacement of plants and knowledge about plants within the Americas deepens our understanding of how power transfers diffusely within settler colonial territories, and more importantly, to recenter Indigenous plant knowledge that precedes colonial science.

Using Indigenous names and uses for plants was an obvious choice but lacked a straightforward path towards resolution. Due in part to the very erasure of local history, tradition, and language that is a fundamental tactic of the settler colonial project, the task of “unnaming” plants remains difficult. This task is further complicated by the broader linguistic structure of, for example in the case of Lenapehoking, the Eastern Algonquin language family, the existence of two Lenape languages (Unami and Munsee) divided into even more dialects, the relationship between the Lenape and the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) in present-day New York state, and the forced relocation of many Lenape people to Oklahoma, Kansas, Wisconsin, and elsewhere, causing changes in language and traditional culture.

Additionally, these oral languages have been transliterated differently by Native speakers and settler linguists of varying places of origin, time periods, and mother dialects and tongues: Southern Unami, Oklahoma Lenape, and Munsee speakers might pronounce or spell the same spoken word a seemingly infinite number of ways, just as the various Swedish, English, and French linguists of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries also all invariably transliterated the same spoken word differently. These languages and dialects themselves are also all influenced by the disparate ideas about naming, classification, and the structure of plants within their respective cultures. Where does a cedar tree begin, and where does it end? Does the cedar tree encompass the roots that extend below it or smoke that extends above it when burned? Is a forest contained in a single seed? Unami and English have different answers. These questions about naming and plants, and whose names to use, continues well beyond the decision to deemphasize the Latin and English names for plants, and points to the need for greater attention to Indigenous peoples and cultures.

Pre-Contact History and Creation Stories

“Indigenous peoples are those who have creation stories, not colonization stories, about how we/they came to be in a particular place-indeed how we/they came to be a place.”

Tuck & Yang, 2003, p. 6

It is difficult to make any broad declarations about pre-contact Indigenous life on Turtle Island, the continent now called North America. Each region has different influences such as climate and land; each tribe has variances in language, beliefs, and customs; each tribe has internal structure. One declaration that can be made is that there was a rich and diverse population of Indigenous peoples and cultures across the land far before any contact from settler colonialists.

Prior to contact, Indigenous cultures had a stronger and closer connection to the land. As our research largely occurred on Lenapehoking, Curtis Zuniga from the Lenape Center spoke with us about the Lenape connection to land. Although not representative of all tribes across this land, we can extrapolate and see the difference from colonists’ beliefs: The Creator gave the Lenape language, knowledge, and guidance to develop customs and lifeways for their existence. The land has a spirit and the Lenape have an affinity toward land as a life giving power that is far greater than any human. Animal spirits would guide the Lenape and tell stories about which plants to use and which ones to avoid. This knowledge became oral tradition and was kept, but not secretly. These stories intimately tied the Lenape to the land and their bodies became vessels for the knowledge that is often passed through creation stories.

Each Indigenous culture has its own creation stories—about the beginning of the world, how crops began to grow, the relationship to animals, how land formations were created, the movements of everyday life like the sun and moon rising, and so on. Creation stories help respect the land as much as physically coexisting with it does. Many creation stories exist in some form or another through websites, books, tribal knowledge, and more. But there remains the likelihood of so many more stories and pieces of knowledge lost because of diseases, warfare, land theft, genocide, and expulsion of Indigenous peoples from their homeland. Without that connection, many cultures adapt, assimilate, or forget.

As European colonizers settled in Indigenous territories in North America, land became property to own and a resource to use, not something to coexist and live with. Coexistence with nature and Indigenous peoples was not an option under settler colonialism. By removing Indigenous peoples from their land via forced migration or confining them to reservations, settler colonists deprive the creation stories of their connection to specific parts of nature and specific land. This connection was further separated as colonizers enforced their version of legibility on the land through the creation of maps. The mere act of map-making usurps the Indigenous names and geographies with outsiders’ perspectives. To this end, we employ counter-mapping strategies here to interrogate and challenge power structures.

Counter-mapping as Method

The colonial world is a world divided into compartments. […] Yet, if we examine closely this system of compartments, we will at least be able to reveal the lines of force it implies. This approach to the colonial world, its ordering and its geographical layout will allow us to mark out the lines on which a decolonialized society will be organized.

Fanon, 1963, p. 38

Like language, maps are often thought of as neutral entities reflecting a common, agreed-upon understanding of the world. This assumption ignores the inherently political nature of cartography and the means by which maps demarcate power: they emphasize it, legitimize it, and perpetuate it, often at the expense of marginalized groups. In the case of settler colonialism, maps have been and are still used to divorce people from land, erect walls between neighbors, and empower and enrich empires: “As soon as lines were drawn on maps by European hands, Indigenous place names, which are intricately connected with Indigenous history, stories, and teachings, were replaced with English names, erasing Indigenous presence from the lands,” (Native Land, 2020). Additionally, many Indigenous peoples hold conceptions of land stewardship that are irreconcilable with the concept of land ownership held by settler colonialists. In this sense, “the map is a form of knowledge that has the power to dispossess” (Hunt & Stevenson, 2016).

Ultimately, maps reflect the ideologies and power structures of the people who made them, and accordingly, they are potent sites for critical interrogation. Maps are, in short, stories we tell about the world, their “absences, their exclusions and omissions, along with the difficulty of actually realizing the lived experience of the spatial knowledge that maps aim to convey, open up possibilities for resisting geographies of power and for a re-mapping of the landscape on other terms.” (Hunt & Stevenson, 2016). This framing invites a reimagining and reclaiming mapping practices in ways that reveal new possibilities for knowing and interrogate the politics of “discovery.”

Counter-mapping refers to a range of methods used to map against dominant power structures in service to anti-authoritarian goals. (Huggan, 1989; Perkins, 2004). Critical cartography, which counter-mapping practices complement and are often embedded within, refers more generally to spatial power and a set of mapping practices and methods of analysis grounded in critical theory which view the map as a tool to perpetuate colonial power (Huggan, 1989; Perkins, 2004; Crampton & Krygier, 2005; Pavlovskaya, 2016). Counter-mapping practices are not just subversive in that they seek to disrupt dominant narratives. Rather, counter-mapping and critical cartography look at both “historic and spatial violence,” challenging the concept that people and their relationship to land can ever be neutral (Hunt & Stevenson, 2016).

There are several subsets of critical cartography and counter-mapping practices, including Indigenous counter-mapping, which refers to the “processes through which Indigenous peoples articulate their presence on and right to defend their ancestral lands, territories and resources against state encroachment, an encroachment which always already occurs within the colonial framework and language of mapping, and which always positions Indigenous presence as that which it must counter” (Hunt & Stevenson, 2016). These efforts are often defined as “decolonial” or “anticolonial” work. (De Leeuw & Hunt, 2017) Anticolonial work focuses on interrogating knowledge production and making visible the places where knowledge is being produced. Decolonization work is aligned with anticolonial work but focuses on how knowledge practices disenfranchise and marginalize specific people, particularly members of Indigenous groups. Indigenous counter-mapping projects tend to use both terms interchangeably to describe their work (De Leeuw & Hunt, 2017).

Non-Indigenous forms of critical cartography and counter-mapping can sometimes constitute decolonial practices by attempting to disrupt dominant narratives and resurface Indigenous knowledge of time, space, and land. Borders, for example, may become more fluid and open to interrogation, redefinition, and remediation (Sula & Daniell 2017). Both critical cartography and counter-mapping provide ways to analyze, critique, challenge, and reimagine connections and accepted binaries such as land/people, body/earth, Native/non-Native, etc.—efforts which can contribute to decolonization and anticolonial work.

For our project, we consulted counter-mapping and critical cartographic practices to inform our decisions, with special attention paid to Indigenous counter-mapping projects and research, two of which we discuss below. Once we determined that a series of maps on both the micro and macro scale would serve as vital visualizations for our data, we approached the map-making process with several critical questions in mind. We asked who is creating the maps, who is compiling the data being used, who is deciding who counts, and whose claims count? We looked critically at the binaristic divides between land and people, earth and body, etc. created by Eurocentric map-mapping practices (O’Brien, 2002; DeLoughrey, Didur, & Carrigan, 2015). While there were technical limitations that impeded some of our efforts to circumvent colonial influences on cartography, using counter-mapping practice as a guiding principle for our work provided a methodology for recentering people on the map and for making the data represent more than just static numbers and inherited names

Several Indiegnous counter-mapping projects were consulted over the course of this project. These projects informed our approaches to recording and visualizing data on Indigenous peoples and native plants. In this respect, two Indigenous counter-mapping projects were seminal works: Native Land and the A:shiwi (Zuni) counter-mapping project.

Native Land seeks to visualize the territories of Indigenous peoples around the world. The project was started in 2015 by Victor Temprano, a settler hailing from Okanagan territory, and is currently in the stewardship of Native Land Digital, a Canadian not-for-profit organization incorporated in December 2018 and Indigenous-led, with an Indigenous Executive Director and Board of Directors who oversee and direct the organization, seeks to unsettle ways of orienting the North American territory. This project allows users to interrogate their perceptions of land, territory, people, and statehood by configuring the map around Indigenous lands, languages, and treaties rather than Western methods or metrics which do not necessarily reflect the categories presented in Native Land.

Similarly, the A:shiwi (Zuni) counter-mapping project seeks to reestablish the relationship between the A:shiwi people and their land, reasserting the importance of experience and stories in visualizing time and space: “The names and images connected with places conveyed a symbiotic relationship between the people and the land.” This project resurfaces the ancestral knowledge and memories imbued in the A:shiwi perspective on the world. In addition to serving as a repository of Indigenous knowledge, this mapping project also hopes to help the present generation of A:shiwi reconnect with their past, emphasizing the spatial and temporal role maps serve in how people position themselves in the world.

Mapping Projects

We produced three digital mapping projects, each engaged with different aspects of plants and place. The first component takes a very local approach, examining the use of plants native to Lenapehoking in a New York City park. The second connects Lenapehoking to the global network of plant transfer and displacement by tracing the origins of the trees planted throughout the city. Finally, the third and final component looks at Turtle Island in its entirety and links bodies, plants, and stories to place.

Native Plants of the High Line

This piece of the project initially set out to visualize the plants in New York City parks, such as Central Park, Prospect Park, and the High Line, in order to understand what the origins of the plants were, and what portion were native to the United States. This raised a number of questions about data, where to source it, and what format would it be in, but also questions about the native-ness of plants. Ultimately the project settled on just analyzing the High Line, due to scale. The High Line is a much smaller park in comparison to say Central Park, and the smaller dataset would be easier to work with in the constraints of a semester-long project. Additionally the “newness” and history of the High Line made it an attractive subject. As long as we could source data for it, we could compare the current park to its past as an overgrown and abandoned rail line, which was an inspiration for some of the gardens. Looking further back we could compare both stages to what would have grown in that space precontact. These three stages—precontact (1609), an abandoned and overgrown rail line (1980s- early 2000s), a public park (2009-today)—provided a dimension of time to compare with the larger class’s goal of exploring space through the use of maps.

The first question about data sources was luckily made easier by the fact that many visitors to the High Line are interested in the plants around them, and the organization that manages the park, Friends of the High Line, has published many lists of the plants used on the High Line, as well as monthly garden highlights and bloom guides that contain location information for around 76% of the plants in the lists. The full plant lists change over time as more sections of the park opened to the public (for example this “Full Plant List” and this one we assume is from 2012 “Plant List”). In 2002, there was a survey of the plants on the High Line, which provided the data for its abandoned state (Stalter 2004). For data on plants in precontact period, we were able to rely on The Welikia Project, which explores the likely 1609 ecology of what is now New York City.

This leads to the second question of nativeness. How would we be defining “native” for the purposes of this analysis? We clearly needed to be more specific than native to the United States, as the US has many different climates and we wanted to represent a more local area. We settled on native with regard to the current State of New York. While going more specific to Manhattan may more accurately reflect some of the goals of the project, we had to contend with how specific this data was represented in other sources. While the USDA can support county-level data for plant statuses, it seemed more consistent and reliable on the state level. Apart from a few interesting cases of hybrid plants, which don’t seem to have a land of “origin” in the sense that we were discussing, between the USDA PLANTS database, Wikipedia, and New York Botanical Garden reports, we were able to source native status for all 500+ plants.

So far no aspect of this project was engaging in the Indigenous sources or knowledge that was an explicit goal of the class’s project. We decided to use the Native American Ethnobotany database to enrich the data with known uses of these plants by tribes whose traditional and ancestral land lies in present-day New York State. This database included uses for 78 plants in our dataset from the Lenape (Delaware), Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), and Shinnecock Tribes. Since we had also established a desire to move away from scientific names and elevate Indigenous names when possible we researched the Lenape names for as many of the plants as we could to help tie the plants back to this specific location and Lenapehoking.

Once we had the data we had to decide on the most effective way of presenting it, which forced a reflection on the goals of the project. Would a basic ArcGIS map, which displayed locations for plants and had a pop-up that displayed a table of information, help users be more aware of the plants around them? Could they even connect the information they were learning to physical plants? We that a more charismatic product was required, one that prioritised images and narrative text. We switched to ArcGIS’s StoryMaps tool to create a tour of plants, and instead of mapping every single plant in the dataset, we chose a subset of all of the plants on the High Line that were also part of the Welikia dataset, around 50 of the original 547 entries. By doing this, we emphasized precontact plants on the High Line and surfaced their stories.

Due to constraints of time, the subset was divided into two groups, a primary tour of 20 plants that have more fleshed out “biographies,” and a secondary tour with the remaining plant names and photos. If a user follows the StoryMaps tour as it is designed the primary tour travels north along the High Line highlighting the plants that we have more information about first before traveling back south along the secondary tour. However users are also able to click around and explore however they like. When possible we used Lenape names, linked to pronunciations, and discussed the plant uses, native ranges, and key characteristics. Hopefully, when paired with the images of the plants, users will be able to walk away from the map with a greater understanding of these local plants, and maybe even the ability to recognize them if they come across them in parks, gardens, and the wild.

Visualizing a World Network of Trees

This part of the project set out to visualize the international spread of plants to understand how the movement of peoples (both forced and unforced) affects the global landscape. This scope was narrowed to trees in the greater New York City (NYC) area using a 2015 Street Tree Census available through NYC Open Data.

From over 600,000 individual trees recorded in the census, a list of 130 individual trees was chosen, one representing each species. The following information for each tree was provided in the dataset and used for the purposes of this project: Latin name, common name, latitude, longitude. The latitude and longitude values refer to the geographic locations of the trees in NYC and were treated as the “destination coordinates” for this project. Research was conducted on each individual species to determine several approximate countries of origin. Approximate countries of origin were based upon online databases, such as the Missouri Botanical Garden Plants Finder. Other notable sources include: The Morton Abortorium, The Gymnosperm Database, The American Conifer Society, among others. Tracking down Native names for the trees was not possible for this part of the project because of the wide range of countries from which the trees originate, as well as with the range of Indigenous territories a single tree species covers.

Trees tend to cross geopolitical boundaries, making it difficult in many instances to identify any one country as the original location for a particular plant. That said, because of the nature of GIS programs, particularly ArcGIS which was used for this portion of the project, a singular set of coordinates needed to be listed as the origin. Thus, the first origin country listed was chosen to represent the approximate location of origin for each tree. Even this required interpretation on our part, as some of the trees had “Northern China” or “Central Europe” listed as their location of origin—regions without precise locations. In most cases, a city located in that region was selected to represent the place of origin. All values described are listed with each point and appear in a pop-up window on top of the map when a user clicks on a point.

Once the origin and destination locations were compiled, the next step was determining how to effectively visualize the movements of these plants to NYC. A goal of this part of the project was to convey that the landscape of, really, any region is inherently political whether one is aware of that or not. Looking towards counter-mapping practices assisted with navigating some of the possibilities. Bringing a general sense of awareness and critical consciousness to one’s environment (Perkins, 2004) seemed like the most attainable goal. ArcGIS provides several mapping options that, to some degree, allow us to bring awareness to the movements of trees and those geopolitical implications. Ultimately, a kind of network map was created using the XY line tool in ArcGIS to connect points on a map using corresponding IDs.This created a network of trees, visualizing the interwoven connections of both the trees and the people who have moved with them into the NYC area.

Now that the data was mapped, it was time to decide how best to present this information. While the map is insightful and compelling, it is not necessarily a critical tool on its own. Some framing was required. How does the data in this map connect to a world history of colonial and imperial rule? More, how can this map be used as a tool for demonstrating the geopolitical implications of our day-to-day landscapes? ArcGIS’s StoryMaps tool was used to create an interactive “home” for this project, providing much-needed context to the data mapped and to how the data was sourced. Users can explore the map as well as find information about why certain categories are represented (such as the Latin name) and why other categories are currently omitted (such as the Native name for the tree in its country of origin). Addressing our own limitations and the limitations of the data available demonstrates for users how knowledge and physical landscapes are both constructed and open to critique.

Body as Botany

In our initial efforts to show the origins of Indigenous plants and the effects of settler colonialism, we were forced to contend with the issues of time and space. How could we show the change of native plants over time? What datasets were available that would even show change over time? We initially sought traditional datasets from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Biodiversity Information Serving our Nation (BISON) from the United States Department of the Interior. While they provided some helpful information in regards to the native status of plants, they didn’t hold any record of the change over time, didn’t show Indigenous uses of plants, and are ultimately representations of settler colonialism, which went against our explicit goals of the project. So we largely abandoned those as a source.

As we discussed counter-mapping, the concept of visualizing this third map and portion of the project as a body emerged. Indigenous knowledge often entwines the two entities which are considered separate in English and in traditional cartography. That separation, though, of land from the body, is a fabrication, a binary prescribed by colonialism and a symptom of a system that profits off of the severing of people from their land. This project sought to re-acknowledge the connection between people and their lands through the creation of a “body map.” One of the initial inspirations for this concept came from an e-literature project called High Muck A Muck (2014) created by an art collective out of Vancouver, British Columbia composed of both Chinese diaspora, self-identified Chinese-Canadian citizens, and other collaborators. This interactive work of e-literature uses the body as a base map, centering the people and reasserting that land and people are one. Even when dislocated, that connection between land and body still exists and is still vital. Though different in conception, this part of the project exemplifies the critical connection between peoples and their land.

Our body map makes use of Native Lands to visualize the rough boundaries of pre-contact Indigenous nations and the Native American Ethnobotany Database (NAEB) for data about Native uses of plants. Dating back to the mid-1970s when it first existed on punch-edge index cards, the NAEB is an extensive database that compiles Indigeneous knowledge of and uses for plants as medicine, foods, ceremony, fibers, and dyes. NAEB currently exists as both an online database as well as a 927-page print reference text. The user is able to search and cross-reference the indices of both the online database and the print reference text according to any combination of tribe, plant, or recorded use. Over 44,000 discrete uses of 4.260 plant species are catalogued and 291 Native American tribes are represented.

While the data represented in the NAEB proved important for this part of the project, our use of the database as a resource was not uncritical. We are, in particular, skeptical of the intentions of many white settler-scientists who compiled its source material in the 19th and 20th centuries—or, as some would say, extracted/bioprospected/harvested Indigenous knowledge. Ethnobotany can be seen as reinforcing the colonialist paradigm that positions Native people as objects of study rather than as collaborators and authors in their own right (as is the case in “autobotany”). Projects like the NAEB, though rich in information, “reassert [Eurocentric] epistemic authority while simultaneously flattening out its colonial pasts and legacies” under the “depoliticized valence” of science (Foster, 2019: 3). While using this database as a tool rather than a touchstone, we were particularly careful not to include any plant uses that could be considered sacred knowledge, particularly uses marked as ceremonial. In addition, we wanted to give greater visibility to Indigenous peoples and cultures by creating an interwoven narrative of native plants, their traditional uses, the tribe that used the plants, and their land.

Our first idea was to create “fake” longitudes and latitudes to form a human shape across the continent. But that brought another slew of questions: Would it be one map for the whole continent, one map per tribe, multiple maps per location? How would we handle the concept of gender, sex, ethnicity, or even cardinal direction orientation? Would our counter-mapping efforts fail to account for the non-dominant viewpoints of place and the body that we wanted to capture? With that in mind and with an interest in surfacing Indigenous culture, we decided to select locations by searching for creation stories of geographical features associated with body parts. For example, if a creation story says a lake was formed from tears, we would connect this story and lake to the eyes. On the other hand, if a creation story details how a giant became a mountain after laying down to take a nap after eating too much, then we would connect this story to the mouth or stomach. We gave up our preconceived notions of what the body would look like and let the research and available data lead us. We relied on manual research and tribal web resources to guide us. As non-Native researchers and limited by a short time-frame, we were unable to verify a greater number of these creation stories by directly contacting the tribes. With more time and resources, collaboration with tribal centers would create greater authority in surfacing Indigenous knowledge.

Initially, we thought there would be a surplus of these creation stories, but finding them provide to be difficult. It may be that there are not as many as we expected, that these are not visible through research tools like Google searches or secondary (written) sources, or that many of these stories have been lost through the ongoing violence of settler colonialism. With 20–25 creation stories identified, mostly about the head, our vision of the body map crystallized into a facial feature map. After pinpointing a story, the next step was to identify the creation story’s tribe and whose land the geographical feature was on. Then using the Native American Ethnobotany Database, we identified the native plants from that tribe’s territory that had the most applicable medicinal use for the creation story. Some connections surfaced quickly, such as a poultice of crushed up leaves to treat sore eyes after crying, while others required some more creativity, such as a plant that stimulated the appetite for a giant who ate too much.

The final piece was the digital display of this map. In order to assert the connection between land and body, we wanted a second “face map” that would link with the spatial map. As our work occurred on Lenapehoking, it felt appropriate to bring attention to a significant symbol of this land and its peoples. So we chose the Mesingw face, a powerful medicine spirit who maintains the balance of nature. Adding this initial face map provides the viewer a visual representation of the connection to the creation stories to come, which shows the close link between the body and land. It also further problematizes the notion of space by having the same facial feature occur across an entire continent.

When the viewer arrives at the site, they are initially greeted by the Mesingw face. Users can click on various facial features, which connect to the map that contains the plants, locations, and stories based on that facial feature. By using ArcGIS Experience Builder, we attempted to realize interactivity and fluidity between the face, native plants, creation stories, and geographical features. We chose real pictures of the native plants in the wild rather than a taxonomy specimen photograph or a botanical illustration in order to distance the plants from any settler colonial influence and to encourage a closer connection to nature. We also attempted to use the Native name of the plant corresponding to each tribe’s use and story, though further research is needed here, given the number and complexity of languages involved.

Reflections

Let us admit it, the settler knows perfectly well that no phraseology can be a substitute for reality.

Fanon, 1963, p. 45

Let us admit it: there is no decolonization without repatriation. No “decolonizing perspectives” or “anticolonial methods” stand in for the overdue return of native land to Native people.

As non-Native occupants of unceded Lenapehoking, we knew we needed to center this project on this land specifically and the Americas more broadly. We decided that our approach should avoid rehashing historical narratives that recast white settlers in the leading role of the drama of colonization and again displace the richness and complexity of the Indigenous peoples and cultures to the periphery. We aimed to uproot the history of plants and colonialism from the historiography of colonialism in order to deemphasize a retelling of the harm done typical of histories of colonization, what Eve Tuck calls “damage-centered research” (Tuck, 2009).

We sought instead to reimagine how this story can be told in a way that foregrounds attention to and surfaces Indigenous wisdom. Thinking deeply about plants offers alternative ways of being-with the world and being-with history. Plants offer insight into ways to be responsible for the world and other co-beings. Donna Haraway emphasizes this approach in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (2016) wherein she introduces the “Chthulucene” as an alternative to the Anthropocene, Capitalocene, and Plantationocene that reconceives of history and temporality by unseating humans as the principal actors in our contemporary geological age and reimagines our role as co-inhabitants in a multispecies ecosystem in a world on the brink of environmental collapse. The Chthulucene takes its name from the soil-dwelling spider Pimoa cthulhu: Pimoa, meaning “big legs” in the language of the Goshute people of Utah, and chthulu, a purposeful respelling of the taxonomist’s nomenclature (“cthulhu”) that reinserts the chthonic into the soil-dwelling, tentacularly limbed spider. As a boundary crosser between death and life, two worlds divided by the soil underfoot, she is a close relative to the Diné’s Spider Woman (Na’ashjé’íí Asdzáá), the Hopis’ Spider Grandmother (Kokyangwuti), the A:shiwi’s Water Spider (K’yhan’asdebi), and the Pueblo people’s Thought Woman (Tsichtinako), all important life-giving figures in their respective cosmologies.

The first step towards creating a new future is to imagine it. Critical to the task of ethical imagining integral to this project was acknowledging the ways in which academic research is always-already structured by a legacy of positivist epistemology that simultaneously delimits our understanding of the world and delegitimizes Indigenous ways of knowing. For Haraway, the Chthulucene offers a way to honor Indigenous cosmologies and reinsert flora, fauna, and arachna into our past-present-future geologic epoch-making and reterritorial counter-mapping. This playful, almost animist approach to time and reconciliation with history provides a way to “stay with the trouble of inheriting the damages and achievements of colonial and postcolonial naturalcultural histories in telling the tale of still possible recuperation,” through recounting “good stories [that] reach into rich pasts to sustain thick presents to keep the story going for those who come after,” (p. 125) and that provide us with new roots and routes forward.

Notes

- For extended versions of the creation story of Turtle Island, see an Ojibwa Elder’s account, an adaptation of a story told by Basil Johnston, The Keepers of the Sacred Tradition of Pipemakers, Native Drums, and The Haudenosaunee Creation Story, among others.

- While we use settler colonial theory as one framework here, we were still forced to reckon with some of its shortcomings. In “Slavery is a Metaphor,” (2020) Tapji Garba and Sara-Maria Sorentino offer a forcible critique of how settler colonial theory tends to diminish the historical role and experiences of Black people in the colonization of the Americas. For example, while Tuck and Yang’s well-circulated article names the settler-Native-slave triad as such, most of their discussion collapses into a settler-Native dyad. Subsuming the distinct experiences of land and repatriation that Native and Black Americans into a monolithic category, ignoring the unique experiences of forcibly relocated enslaved Africans and their descendents, and skimming over the foundational role that chattel slavery played in settler colonism are all commonly reproduced pitfalls with settler colonial theory. Similarly, our project does not address this issue, though we believe plants may be a useful window here as well.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Lenape people, the original caretakers of the land on which Pratt Institute sits and on which most of our project work has occurred. In particular, we wish to thank Curtis Zuniga of the Lenape Center and Delaware Tribe of Indians for his dialogue with us about Lenape people, culture, and their relationship to the environment. We also acknowledge the many Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island, whose stories and lifeways have informed this project. We also wish to thank Prof. Dan Moerman and the many contributors to the Native American Ethnobotany Database. We are grateful to Prof. Nancy Smith for suggesting many readings about plants and the environment at the start of our project, and the team at Pratt SAVI (Spatial Analysis and Visualization Initiative), who provided guidance in formatting our data and using the full suite of ArcGIS tools for visualization. Finally, we are grateful to members of the Pratt community who attended our work-in-progress presentation on November 19, 2020 and provided helpful feedback.

References

Brockway, L. H. (1979). Science and colonial expansion: The role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens. American Ethnologist, 6(3), 449–465. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1979.6.3.02a00030

Crampton, J. W., & Krygier, J. (2005). An introduction to critical cartography. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 4(1), 11–33.

Crosby, A. W. (1972). The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Greenwood Publishing Company.

Crosby, A. W. (1986). Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900. Cambridge University Press.

Davis, J., Moulton, A. A., Van Sant, L., & Williams, B. (2019). Anthropocene, capitalocene, … plantationocene?: A manifesto for ecological justice in an age of global crises. Geography Compass, 13(5), e12438. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12438

de Leeuw, S., & Hunt, S. (2018). Unsettling decolonizing geographies. Geography Compass, 12(7), e12376. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12376

DeLoughrey, E., Didur, J., & Carrigan, A. (2015). Introduction: A postcolonial environmental humanities. In Global Ecologies and the Environmental Humanities (pp. 19–50). Routledge.

D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2020). Data feminism. MIT Press.

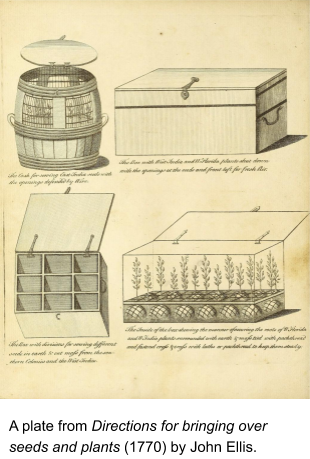

Ellis, J. (1770). Directions for bringing over seeds and plants, from the East Indies and other distant countries, in a state of vegetation: Together with a catalogue of such foreign plants as are worthy of being encouraged in our American colonies, for the purposes of medicine, agriculture, and commerce. To which is added, the figure and botanical description of a new sensitive plant, called Dionaea muscipula, or, Venus’s fly-trap. London: Printed and sold by L. Davis.

Fanon, F. (1963). The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Press.

Gabrys, J. (2013). Digital rubbish: A natural history of electronics (p. 243). University of Michigan Press.

Garba, T., & Sorentino, S.-M. (2020). Slavery is a metaphor: A Critical commentary on Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Antipode, 52(3), 764–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12615

Gil, A., & Ortega, É. (2016). Global outlooks in digital humanities: Multilingual practices and minimal computing. In Doing Digital Humanities (pp. 58–70). Routledge.

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Huggan, G. (1989). Decolonizing the map: Post-colonialism, post-structuralism, and the cartographic connection. ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 20(4).

Hunt, D., & Stevenson, S. A. (2016). Decolonizing geographies of power: Indigenous digital counter-mapping practices on Turtle Island. Settler Colonial Studies, 7(3), 372–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2016.1186311

Kincaid, J. (2020, September 7). The disturbances of the garden. The New Yorker, 24–26.

Kauanui, J. K. (2016). “A structure, not an event”: Settler colonialism and enduring indigeneity. Lateral 5(1). https://doi.org/10.25158/L5.1.7

Lafuente, A., & Valverde, N. (2016). Linnaean botany and Spanish imperial biopolitics. In L. Schiebinger & C. Swan (Eds.), Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (pp. 134–147). University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated.

Lenape Language Database Project. (n.d.). Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://grantome.com/grant/NSF/BCS-1064636

Liu, A. (2012). Where is cultural criticism in the digital humanities? In M. K. Gold (Ed.), Debates in the Digital Humanities (pp. 490–509). Univ Of Minnesota Press. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/20.

Moerman, D. E. (2003). BRIT – Native American Ethnobotany Database. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from http://naeb.brit.org/

Moerman, D. E. (1999). Native American Ethnobotany: Foods, Drugs, Dyes, and Fibers of Native North American Peoples. Daniel E. Moerman.

Native Land Digital. (n.d.). NativeLand.ca. Native-Land.ca – Our Home on Native Land. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://native-land.ca/

O’Brien, S. (2002). The garden and the world: Jamaica Kincaid and the cultural borders of ecocriticism. Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, 35(2), 167-184. Retrieved December 13, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/44029988.

Pavlovskaya, M. (2016). Digital place-making: Insights from critical cartography and GIS. In C. Travis & A. von Lünen (Eds.), The Digital Arts and Humanities (pp. 153–167). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40953-5_9

Perkins, C. (2004). Cartography – Cultures of mapping: Power in practice. Progress in Human Geography, 28(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132504ph504pr

Remy, L. (2018). Making the map speak: Indigenous animated cartographies as contrapuntal spatial representations. 7, 21.

Schiebinger, L. (2004). Plants and Empire: Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World. Harvard University Press.

Schiebinger, L., & Swan, C. (2016). Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated.

Segalo, P., Manoff, E., & Fine, M. (2015). Working with embroideries and counter-maps: Engaging memory and imagination within decolonizing frameworks. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3(1), 342–364. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v3i1.145

Sinclair, S., & Poplawski, V. (2018). Digital environmental humanities: Strong networks, innovative tools, interactive objects. Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities 5(2), 156-171.

Sula, C.A., & Daniell, R. (2017) Mapping and countermapping borders [conference presentation]. HASTAC 2019. Unceded Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm) Territory, UBC Vancouver, 17 May 2019.

Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, education & society, 1(1).

Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research 8(4), 387–409.