Mapping Provenance: Navigating the Narratives of Nazi-Looted Artworks

By Emma Boisitz, Craig Nielsen, Nicoletta Romano, Miranda Siler, and Chris Alen Sula

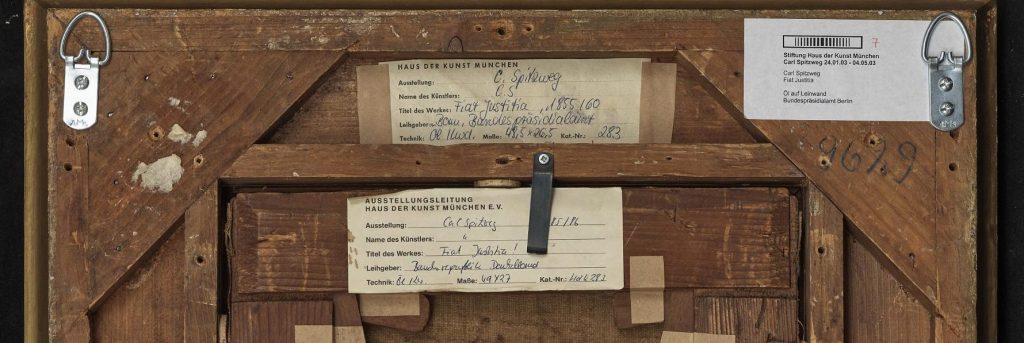

Description and exhibition labels of Carl Spitzweg’s Das Auge des Gesetzes (Justitia). Photo courtesy of Neumeister Münchner Kunstauktionshaus.

This study examines the availability of provenance data (or lack thereof) and use of visualization techniques to support the restitution and/or repatriation of stolen artworks. Through several case studies of Nazi-looted artworks, we explore the potential of narrative design and develop mapping interfaces that bring new life to the storied past of these artworks. In some cases, we find clear evidence in the data record of theft, destruction, sale under coercion, and similar misdeeds. In others, we find gaps that are suggestive of these or other acts, and on the whole, we point to the need for more thorough, structured provenance data to support researchers and those seeking recompense—not only for Nazi-looted artworks but also for other objects of colonial plunder.

Context

This project was completed through a graduate course, the second in a sequence following an introductory survey of digital humanities, its methods, tools, and impacts. Students and faculty worked together as co-researchers on this project, following principles set forth in UCLA’s Student Collaborators’ Bill of Rights. The course is situated in an iSchool, which focuses on relationships between information, people, and technology. Several students in the course have a background in art or art history and are pursuing a dual degree in this area. These disciplinary and methodological framings are reflected in the content of this project, which centered on the circulation of artworks and their place in larger cultural and political narratives. We begin by painting this larger background, followed by discussion of the data structures and digital tools employed in our case studies.

Nazi-looted artwork and its afterlives

In the late 1930s, Lea Bondi Jaray left behind her home, belongings, and art gallery in Vienna as she and her family fled Nazi persecution of Jewish people in Germany and Austria. She reclaimed her gallery after the war ended in 1946, but a painting she had been coerced into giving to a Nazi art dealer was no longer among her belongings. The Portrait of Wally Neuzil by Egon Schiele, an expressionist, had disappeared. “Why don’t you give in? We may want to leave already tomorrow, and don’t make any difficulties. You know what he can do,” her husband said of the art dealer’s persistent and “unpleasant” pursuit of the painting.1 Lea Bondi requested that a collector interested in Schiele retrieve her painting from the Austrian Gallery, where the Nazi art dealer had told her it was moved to after the war. It had mistakenly been identified as part of another collection in the hectic repatriation attempts.2 The collector, Dr. Rudolf Leopold, then became the “owner” of the painting and eventually left his collection to become part of The Leopold Museum. Lea Bondi died without compensation or restitution and The Leopold Museum claimed a good sale until a settlement was reached between Bondi’s heirs and the museum. In exchange for $19 million, the museum would be allowed to keep the painting.

Lea Bondi’s story highlights the difficulties in many Nazi-looted art narratives: a coerced sale, the complicated shuffle of art after the end of the war, an unethical collector, long years of searching and battling, and a legal system not designed to handle such cases. Looting encompasses not only art stolen from people and institutions, but also the coerced and forced sales people made to party officials as they prepared to leave their homes or were forced to give up their businesses. Through these processes, Nazi officials and collaborators enforced their ideal of art and amassed the cultural heritage of occupied lands. Modern art, like the Portrait of Wally Neuzil, was excluded from this ideal. As early as 1933, just after Adolf Hitler became chancellor, a modern art exhibition was forced to close after being open for only twelve days—a result of a negative review in the local Nazi press.3

Throughout the 1930s, the Nazis seized many artworks from German public institutions that were deemed “degenerate,” most of which were stylistically modern or had Jewish or otherwise undesirable creators. These works were used as both propaganda and bargaining chips, and in both cases their effectiveness hinged on provenance. When displayed in travelling Degenerate Art Exhibits throughout Nazi territory, the artworks were often displayed alongside information about their previous museum home and how much the curator had paid for them. Fleckner writes, “Next to the price there would often be a sticker telling the visitor that the artwork had been ‘bought with tax revenues taken from the hardworking German people.’…The provenance information supplied in this manner deliberately brought all progressively run museums into discredit, and with them the emerging cultural identity of the Weimar Republic, the democratic state that had sanctioned the purchasing policy in the first place.”4 As we will see, the decision to display, obscure, research, or ignore provenance information is inherently political—a practice as true today as it was during Nazi era.

Art deemed acceptable by the Nazi party, largely “Old Masters,” such as Leonardo da Vinci or Raphael, or landscapes or non-modern paintings of Germanic origin were separated from their rightful owners. Their intended destinations were grand museums of Hitler’s design, including the House of Germanic Art, which opened in 19375 and is currently known as the House of Art. These artworks also entered the personal collections of Nazi officials and collaborators, building their wealth from the stolen and confiscated art of others.6 The unacceptable or “degenerate” art was also taken into the personal collections of Nazi officials, despite the public disparagment of such works.

The amount of looted art grew as more territory was seized and as the restrictions around Jewish life tightened. The ERR, or the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, was the arm of the state in occupied territories when it came to plundering cultural heritage.7 Private collections, particularly those of Jewish owners and critics of the state, were not protected from confiscation and were subject to the circumstances of the time. Even before they were forced to flee or give up their businesses to non-Jewish Germans, people sold their art under duress to cover the cost of escaping. Others, like Lea Bondi Jaray, were coerced into giving up their property. Restituting and repatriating this art after the war has proven to be a long and chaotic process, with many who are denied justice or, like Lea Bondi Jaray, do not live to see justice done.

The Nazi position around provenance changed at the end of the war. As Germany was forced to pay off debts, suddenly any remaining looted artworks became monetary assets. In June of 1939, artworks such as Picasso’s Absinthe Drinker and van Gogh’s Self-Portrait were auctioned off to raise money for the Nazi party.8 The official policy was to remove provenance information, in the form of sale stickers on the back of an artwork, because the Nazis were aware of the bad optics associated with their looting activities. This policy was rarely enforced however, because the authenticating power of provenance ultimately made these works more valuable. Seized artwork was sold for high profit in public auctions, often to buyers in the Allied territories. Other so-called “degenerate” art was confiscated and destroyed.9

Restitution (return of ownership to an individual) and repatriation (return of ownership to a state) have long been the focus surrounding artifacts seized by the Nazis during the 1930s and 40s. Groundwork for restitution and repatriation efforts began during the war. Governments operating in exile declared the confiscation and looting of artworks and other objects null and void.10 However, since the war ended and these efforts began, legislative and legal efforts have been complicated. The Allies ordered the seizure of any objects that had been looted, confiscated, or sold under duress and began efforts to organize and return art, albeit slowly. The United States, the Soviet Union, France, and the United Kingdom were unable to agree on cohesive restitution laws in their occupied territory until the end of the 1940s. This variety of approaches in restitution laws remains an obstacle for efforts through the present day. Each country’s legislative history supports different approaches and, in the US, these laws may even vary from state to state.

There have been many recommendations for rectifying such complications, but legislative results have been slow in coming. The Washington Conference on Holocaust Era Assets, held in December 1998, released a list of principles including establishing easier and faster methods of restitution.11 These recommendations were made once again in 2009 at the Prague Holocaust Era Assets Conference in Terezin. Representatives of forty-six countries met to discuss progress and address further issues. They advocated for the consideration of restitution claims “based on the facts and merits of the claim” and for ensuring that legal processes were not an obstacle to resolution.12 In the US, where many efforts have been blocked by restrictive statutes of limitations, the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act (or HEAR Act), passed in 2016, established a national uniform statute of limitations of six years after discovery and denial of first recovery attempts.13

Another obstacle to restitution is countries who wish to protect their own imperialist plunderings from successful restitution and repatriation efforts. When establishing processes of restitution in post-World War II Europe, Allies limited restitution to objects looted after 1937—anything earlier would have threatened some items their own state collections.14 This framework has a negative impact on all restitution efforts, including Holocaust-Era efforts, which the aforementioned imperialist powers have deemed to be acceptable. Even within these parameters, the eagerness to hold onto their looted art results in many museums willfully ignoring the call for greater provenance research, and in some cases, even going so far as to hinder those efforts.15 Both legal loopholes and a purposeful lack of research highlight the importance of gathering and examining provenance data as a means of advocating for justice for all who have had their cultural heritage stolen from them. In order to properly support and continue those efforts, provenance information must be available and ready to use.

The complexity of provenance information

Most museums, galleries, and private collections maintain ownership and transferral data about their artworks. Known as provenance, such data is the raw material for representing journeys of artworks, and is the key to envisioning restitution. However, there currently isn’t a standardized way of representing that data, as provenance research remains relatively siloed, and art institutions often utilize their own vocabularies. Thus, if one wanted to aggregate large amounts of provenance data, compare it, or visualize it en masse, they would first have to convert that semi-structured text into structured data. This requires a lot of standardization labor—known in information science as “crosswalking”—which may get unnecessarily repeated across different digital humanities projects. The lack of formal standards also impedes discoverability of artworks’ distinct stories.

Certain improvements in this situation, regarding both standardization and the availability of provenance data, have occurred in the last twenty years or so. In 1998, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) and American Alliance of Museums (AAM) issued guidance to its members on identifying works with Nazi-era provenance and, in 2000, mandated the publication of records for works that may have been unlawfully appropriated. This included requirements for the publication of the provenance of artworks and suggestion of standards to communicate these records which reads, “To contain, at the minimum, known owners, dates of ownership, places of ownership, method of transfer (sale, gift, descent, etc.). To include, if known, lot numbers, sale prices, buyers, etc. To include information on unlawful appropriation during the Nazi era and subsequent restitution. Museums should ensure that provenance information is understandable and organized chronologically.”16

Many museums have adopted the AAM suggested format for the publication of their possibly-looted works within the Nazi-Era Provenance Internet Portal, but there is still a wide variation to the amount of provenance data that they include on their own websites, if they include any at all. For example, the National Gallery of Art includes a very brief description:

(Galerie Kurt Meissner); acquired 1987 by the National Gallery of Art

Others are very explicit, including footnotes with sources, like the Saint Louis Art Museum:

1946

Max Beckmann (1884-1950), Amsterdam, The Netherlands [1]1946

Buchholz Gallery (Curt Valentin), New York, NY, USA, acquired from the artist [2]1946 – 1955

Wright S. Ludington, Santa Barbara, CA, purchased from Buchholz Gallery [3]1955/12/04 – 1983

Morton D. May (1914-1983), St. Louis, MO, purchased from Wright S. Ludington through Stephan Lackner [4]1983 –

Saint Louis Art Museum, bequest of Morton D. May [5]Notes:

[1] Max Beckmann kept lists of most of his paintings which often included the dates that they were worked on. This painting is included in Beckmann’s Amsterdam list. Beckmann notes that he worked on the painting around August 25, 1939 [Göpel, Erhard and Barbara Göpel.”Max Beckmann: Katalog der Gemälde.” Bern: Kornfeld & Cie., 1976, cat. no. 536].[2] Beckmann shipped “Acrobats” to his dealer, Curt Valentin, in New York, for an exhibition of his work held from April 23 to June 25, 1946. According to the handwritten shipping record, the painting was one of fourteen works on the ship “Delftdyk” which left Rotterdam, The Netherlands, on January 14, 1946 and arrived in New York on February 9, 1946 [Curt Valentin Papers, Museum of Modern Art, New York].

[3] By the time the exhibition catalog for the Curt Valentin show was published, the painting was already listed as being in the collection of Wright Ludington, indicating that it had been sold by that time [“Max Beckmann: His Recent Works from 1939 to 1945.” New York: Buchholz Gallery (Curt Valentin), 1946, cat. no. 1]. On April 1, 1946, Valentin reported to Beckmann that he had already sold the “Acrobats” to Ludington [Curt Valentin Papers, Museum of Modern Art, New York].

[4] The sale of the triptych from Ludington through Lackner to May is documented in correspondence and a bill of sale dated December 4, 1955 [May Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum].

[5] Last Will and Testament of M. D. May dated June 11, 1982 [copy, May Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum]. Minutes of the Acquisitions and Loans Committee of the Board of Trustees, Saint Louis Art Museum, September 20, 1983.

Converting unstructured or semi-structured provenance information into structured metadata requires understanding provenance as a timeline comprising a linked series of intervals demarcating each period of ownership. In addition, the following information about each interval is required:

- acquisition method (purchased, looted, inherited, etc.)

- geographic location

- custody

- timespan

- footnotes (unstructured data)17

Each of these requires a controlled vocabulary, such that discrete access points can be encoded into the metadata. For geographic location, this may entail representing places using an external authority such as Geonames or the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names Online In other cases, brand new controlled vocabularies might need to be developed in consultation with provenance researchers.

Developing a structure for this data entails making a provenance standard, which resolves ambiguities and enhances interoperability between datasets. A text-based provenance standard could then be paired with a software library (or viewer) that can parse records written using this standard and convert them into structured data. Provenance metadata standardization thus allows researchers to pose newfound questions about the movement and transfer of large numbers of artworks.

At the time of this writing, there have been a few attempts to create an ontology that can handle provenance information. The W3C Prov Working Group has a goal of creating a schema that can work in RDF, XML, or other markup languages, and is also interoperable with other ontologies like Dublin Core. Their model is centered around three types: agents (people and organizations), objects (the artworks themselves, also called entities), and processes (activities and events). The schema aims to describe the relationships between these various types, as seen in the figure below.

Another provenance data schema is the one developed for the Getty Provenance Index (GPI). While this searchable database of provenance information is used by many, there is little evidence of others using this data model for their own purposes. While the GPI is the largest aggregator of provenance data, it still draws from limited sources, mostly ledger books from Western European art dealers, thus limiting the types of artworks and transactions represented in the database.

Another attempt at creating a provenance data model is happening on Wikidata, through WikiProject Provenance. This seems to be a fairly small effort, with only ten properties and a handful of relevant examples. Unlike the super specific types of information that the GPI describes (for example, start_price_curr, alphabetic or currency recorded for the starting price for the lot), WikiProject Provenance has a more simple data structure with information like creator, owned by, and collection. One property that is very interesting is “significant event” which can be used to make the connection between a work and Nazi looting activities. At the time of this writing, 41 works have been tagged with the significant event “Nazi Plunder.”

Existing projects on provenance mapping / user research / tools

In trying to aid in the comprehension of Nazi-looted art, we have sought to emphasize the stories of the artworks and those affected by looting. As a result, we found ourselves drawn to the practice of “visual storytelling,” in which maps are “potentially just one scene in the overall story,” as we also relied on text and images to bring life to these narratives.18 At the same time, we recognize that, in deciding to use mapping as our method, we have also made intentional and subjective choices, including determining “mappable” case studies to include and what points are mapped. Additional choices, from the genre of our story maps—whether dynamic slideshows or longform “scrollytelling”—to certain tropes we have implemented, such as continuity, mood, dosing, attention, and even voice in the form of this “reflexivity statement”19 (along with others throughout this essay), illustrate that our visual stories are ultimately constructed representations based on actions of power we acknowledge to have taken as project creators.

We initially conducted a survey to analyze similar projects in the fields of digital art history and digital humanities to examine the strengths and weaknesses of those maps, as well as to identify where our own mapping project would fit within this landscape. Of these projects, Mapping Paintings and Footprints were particularly relevant for work with provenance data.

Mapping Paintings invites users to follow the journeys of paintings that have already been mapped using available provenance data, and to create custom mapping projects by uploading additional data to the site. This project was developed by Jodi Cranston in an originally scaled-down version known as Mapping Titian, before expanding its content to become a more crowd-sourced platform.20 Mapping Paintings ultimately explores the promise of narrative design in the geographic visualization of provenance information, allowing for new questions and perspectives about these artworks, their routes and their stories to emerge, as traditional ideas and representations of provenance are challenged.

Footprints: Jewish Books Through Time and Place similarly traces provenance journeys, but in this case as its subtitle suggests, the focus is on the diasporic circulation of printed Jewish books, which encompasses works in Hebrew and other Jewish languages, as well as “non-Jewish vernaculars with Judaica contents.” Through its Pathmapper network visualization, this project encourages users to investigate the movements, histories, and patterns of ownership of these footprints, the “record[s] of the material presence of a literary work at a particular time and place.” Footprints began in the discussions of the Center for Jewish History’s Scholars Working Group on the Jewish Book, and has since been developed with additional partners, including the Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning, where it is currently hosted. The project’s use of archival information and the books themselves as evidence reveal the richness and intricacies of multiple provenance sources in building a database and record of Jewish book history and culture.

These projects served as the basis for gathering feedback in a first round of user research. Our class members met with students, faculty, and others with an art history background in one-on-one sessions of thirty minutes each. We observed users as they navigated these two projects, along with one of our own prototypes, and talked with them about issues such as ease of use, navigability, design, and narrative structure. The results of this feedback, together with a public presentation of initial designs to our school community, including many digital art historians and digital humanists, informed the creation of our own maps. Key points of feedback included:

- First, users all preferred having the provenance data and a small summary at each point of the journey to provide additional depth and context.

- Another important element was showing temporality on the map. Some users expressed wanting a clearer journey through the story being shared while still being able to click and navigate freely on the map. Directions on the lines or numbered points were a common suggestion.

- The maps varied in navigation difficulty, with some stumbling blocks that all users found difficult to work with in using the maps. While being able to click and explore around the map was desirable, having to move too many times and jump through too many structured hoops to get to the map itself was not.

- Users wanted a structured story that they could clearly see while also being able to explore the map and explore the different options presented to them. This included being able to go back and forth and jump around on a structured story map and being able to toggle on and off multiple objects that were congregated on the same map.

- At the public presentation, participants urged us to visualize the original owners of the artworks, their lives, and collections, as well as the artworks themselves, rather than centering narratives of theft and destruction.

In light of this user feedback, we evaluated tools which would permit us to create narrative maps with flexibility and employ the suggestions of the test users.

From the beginning, our aim was to understand and map the provenance of Nazi-looted artworks, while also telling the stories behind these paintings and of the people associated with them. After having met with Pratt Institute’s Spatial Analysis and Visualization Initiative (SAVI), who helped us identify tools that would best accomplish this intersection between mapping and storytelling, we experimented with Esri’s ArcGIS StoryMaps, a proprietary web application, as well as open-source alternatives, such as KnightLab’s StoryMapJS and Open Knowledge Foundation’s TimeMapper. In each of the case studies we’ve investigated, different applications of these tools are presented, as well as their successes and failures in addressing additional themes or questions in our work.

Inspired by observations in our initial landscape analysis and the feedback we received in our user studies, we developed a set of principles guiding the development of our case studies. First, we sought to strike a balance between a granular view of data and wider narratives associated with the artworks that we considered. This required the availability of captions and commentary, not just labels for our provenance data. Such commentary, in turn, relied upon extensive research about the individuals and artworks, research that exceeded what was available through the provenance data alone. In doing so, we sought to redirect attention to the stories of artworks and the people associated with them, rather than Nazism and its acts of theft or destruction. Second, we aimed for a thoughtful integration of time and space in our case study visualizations. In addition to mapping temporal and geographic points, this required demonstrating contiguity between a past era of looting and the ownership of present holdings. We felt such a linkage was necessary for insisting upon a narrative of eventual restitution. Third, we sought tools that excelled from a design standpoint, allowing for customization of aspects such as basemaps, borders, as well as overall look and feel. On the whole, we gravitated toward tools that we felt demonstrated both ease of use and accessibility, bearing in mind potential applications by others, should provenance data become more available in the future.

Case studies

As we chose our tools, we also began examining the types of cases and questioning which specific artworks to research and map. The case studies cover a variety of results in the restitution and repatriation process. By doing so, we were able to examine the efficacy of different tools and methods to properly convey the stories of these artworks and their contexts. The case studies show not just the distance of land covered by these journeys, but the lengths to which families and countries have gone in order to regain their property and their cultural heritage.

Camille Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré… (1897) – StoryMaps JS and TimeMapper

By Craig Nielsen

An initial case study we pursued was the fascinating provenance of Camille Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré… as it exchanged ownership throughout Europe and the US. Completed by Pissarro in 1897, the painting depicts a Parisian street and is notable for marking the artist’s return to a loose impressionist style, following an engagement with pointillism. For the beginning of the painting’s life, it belonged to the Cassirers, a German Jewish family, but it was sold under duress to a Nazi art appraiser in 1939 for a fraction of its true worth. It soon found its way into the US, where it bounced between several galleries and private collectors. Eventually it landed back in Europe, having been purchased by Swiss industrialist Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza for his private collection in Madrid, which was eventually converted into an art museum. Still awaiting full restitution, Rue Saint-Honoré… has been subject to numerous legal claims originating from the heirs of the original Jewish owners.21

This artwork made for a great initial case study due to its dizzying trajectory, not to mention the various legal cases associated with it. Additionally, the painting was not directly looted, but was sold under unfavorable conditions, in this case to secure exit visas for the Cassirer family out of Germany. Lastly, it was an object that arrived in the US, likely before 1945, demonstrating the geopolitical agnosticism of the international art market. As such, our question became how to represent the object’s journey. Given that the painting was an individual item rather than a set of artworks, a hybrid map-timeline format proved to be the best available option. We experimented with two different hybrid map-timeline tools, Knight Labs’ StoryMap JS and Open Knowledge Foundation Labs’ TimeMapper. Both visualization tools took similar inputs, and both registered various strengths and weaknesses.

StoryMaps JS was the first attempt, and a prototype version of the map became one of our examples in gathering user feedback (alongside the Mapping Paintings and Footprints projects). StoryMaps JS is basically a slideshow of different geographic points, with distinct slides corresponding to predetermined locations on a map. It offers the ability to caption each point with a title, a description, and an image. From the creation side, StoryMaps JS is a streamlined platform that is readily accessible to anyone looking to juxtapose geographic locations to tell a story. From the user side, it is a straightforward and rather simple upgrade to a more typical textual narrative format. Its storytelling function is unidirectional—a user can only move forward or backward in the journey, not hop between points. However, we found that making the final slide in the StoryMaps the present year (2021) generated a sense of connectivity between the present day and these historical events.

OKFL’s TimeMapper formed the second attempt at representing the same provenance data and description about the Pissarro painting. To be precise, TimeMapper is technically a timeline-building tool with an OpenStreetMap widget tacked onto it, which occupies the right side of the screen. Pushpins on the map correspond to different items on the timeline, and they light up as a user moves through the timeline. Similarly to StoryMaps JS, TimeMapper allows the incorporation of titles, descriptions, and imagery for each entry. Unlike StoryMaps JS, TimeMapper doesn’t have an edit/workstation mode. Instead, the creator must input all of the requisite data into a spreadsheet document (the formatting for which is provided by the OKFL), and upload the spreadsheet to the TimeMapper tool. TimeMapper then processes the spreadsheet and generates a hybrid chronological-geographic representation of the data.

TimeMapper offered a strict upgrade to StoryMap JS, at least for this particular case study. The reasons for this were threefold. First, the generated TimeMap formed an explicit pairing of chronological and geographic data, neatly condensed in each data point. In contrast, StoryMaps JS offered only a juxtaposition of geographic data points. With StoryMaps JS, one could merely add the “illusion” of chronological progression by appending a date to each slide’s title and/or description, but that data was not hard-coded to the same degree as TimeMapper. Second, TimeMapper introduced the ability to overlay points on a timeline, whereas StoryMap JS only offered discrete narrative points. This was an overall improvement in visualization capacity, because there were aspects of the Pissarro painting’s journey that required representing a certain degree of simultaneity, as well as distinction between events and durations. Events corresponded to things like transfers in ownership, or the emergence of legal claims; durations corresponded to periods in ownership, some lasting several decades. Although slightly more complicated to format and devise, the spreadsheet format of inputting the data allowed for the designation of durational entries on the TimeMap, as well as the overlaying of events atop those durations. Third, the TimeMap offered users the ability to navigate non-sequentially, by simply clicking pushpins on the map or regions of the timeline. Again, this presented an improvement over the comparatively teleological approach of StoryMaps JS.

Lasar Segall’s Eternos caminhantes (The Eternal Wanderers), 1919 – ArcGIS Storymaps Map Tour Feature

By Miranda Siler

The work on the map of Eternos caminhantes started while browsing through the Freie Universität Berlin “Degenerate Art” Research Center’s database of degenerate artworks. Most of the works within the database have some scant provenance and exhibition information. Eternos caminhantes seemed to be a compelling piece; the themes of displacement and wandering made it an appropriate fit with the project. Also, the fact that it ended up in Brazil suggested an interesting journey. The provenance information provided reads:

1919 – 07.1937: Dresden, Stadtmuseum

07.1937 – unknown: German Reich / Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Berlin.

Seizure

Note: Per “Law on Confiscation of Products of Degenerate Art” of May 31, 1938, confiscation without compensation in favor of the German Reich

1938 – xx: Velten / Mark, depot for propaganda exhibitions Storage of the exhibits for the traveling exhibition “Degenerate Art”

xx – after 1954: Paris, Emeric Hahn

after 1954: São Paulo, Museu Lasar Segall

While this was a useful starting point, I quickly realized that there was more to the story. I noticed that a couple of articles22,23 that I read about the piece mentioned that it was found in the basement of a Nazi official. After some further research I was able to verify this claim through some documents presented in an exhibition catalog for “A Arte Degenerada de Lasar Segall: Perseguição à Arte Moderna Em Tempos de Guerra” (Lasar Segall’s Degenerate Art: Persecution of Modern Art in Times of War), which was held at Museu Lasar Segall in Brazil. The museum website also gave me a lot of great information about the artist himself, which added further context to the work. It became clear that a list of dates, owners, and places alone would not accurately reflect the journey of this piece. This was especially true for steps in which very little information is known.

During this research phase, the group received two rounds of user feedback which definitely changed how I approached this work. The first round of users seemed to prefer a map that they could explore themselves at their leisure, as opposed to something guided. This encouraged me to flesh out a map of the Degenerate Art Exhibitions, as opposed to focusing on the journey of a single artwork. But the second round of feedback indicated that users would prefer more of a narrative, and I switched my focus back to the Eternos caminhantes map. I was ultimately very happy with this decision. One of the reasons that the storymap of a single artwork is preferred over the exploratory map of degenerate art exhibitions is that it centers the work and the artist instead of Nazi activities. It feels like a revolutionary act to explore and celebrate a work’s impact before and after looting by the Nazis, and it is a more clear way of breathing life into these works. I ultimately included a more guided narrative map of the painting’s journey as well as an exploratory map that details some basic information about the Degenerate Art Shows where it was exhibited.

The tool that I used was ArcGIS Storymaps, which I found to be user-friendly and easily customizable. I think that having the ability to write text outside of the maps was really helpful, since I was able to give a fuller picture of Lasar Segall’s life and work. Within my provenance map, I think that the map tour feature did a pretty good job of integrating time and space. I was able to put each point on the map in an order, which proved especially useful in cases when only relative position, not exact dates, were known. In fact, I was able to create points in the journey (slides) that did not have a corresponding location, date, or image. I relied heavily on captions and commentary to tell the story of this artwork. Looking back at the original provenance string that was the basis for this work, it is clear just how much is missing with the lack of supporting text. It does not accurately represent the bittersweet feeling accompanied with the final leg of the painting’s journey. While the piece has made its way into the hands of the artist’s heirs, the transaction was not one of restitution, but rather a series of sales that ultimately benefitted a private dealer and the Nazi party. While it doesn’t seem like there’s any room for legal action, perhaps a donation from the still-active Galerie Emeric Hahn to the Museu Lasar Segall could act as a gesture of goodwill. I would not have been able to express any of these sentiments without the ability to provide explanatory text.

My one complaint about this tool was that I found it difficult to find a basemap that fully accomplished what I wanted. I think that using present-day borders and labels can be misleading, but I had trouble finding an appropriate alternative within Esri’s basemap collection. I ultimately opted for a basemap that had a mid-century feel with muted tones in alignment with the actual work. I think that in a perfect world, I would have created my own basemap and used that, but timing did not allow for that in this round of work.

Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man (1514) – ArcGIS StoryMaps Explorer Map Tour

By Emma Boisitz

In the plundering and shuffling of art before, during, and after the war, many items have been lost or destroyed along the way. Collections survive in bits and pieces, scattered across a wide area. The Portrait of a Young Man was stored with Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine and Rembrandt’s Landscape with a Good Samaritan when they left the museum on August 24, 1939. They were removed from their places on the walls of the Czartoryski Museum and then placed in a wooden trunk, bound for safekeeping from the coming war.24 While the works by Leonardo and Rembrandt were repatriated and are exhibited in the museum, the Portrait never returned to the collection again. For years, rumors have persisted regarding the location and survival of the portrait, but each time no results have come about.25 As a case study, this artwork was an exercise in mapping uncertainty and grappling with how to visualize gaps. Not only has this piece been missing since the end of World War II, there is a significant gap in its provenance between creation and purchase by the Czartoryski family where no one is certain who owned the piece of where exactly in Italy it was.

This artwork presented an interesting challenge in provenance research, but also a worthwhile case study. Although the portrait now belongs to the Princes Czartoryski Museum and will be exhibited there if the painting is ever found, there is no entry for this item in the museum’s catalog. It is instead recorded in the Catalogue of War Losses maintained by the Department for the Restitution of Cultural Goods in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Poland’s government.26 They do not record provenance information in this catalog, but rather details about the object such as object title, artist, date, and medium. There is no summary of provenance to begin sketching a journey and the Catalogue of War Losses does not include last sightings or last known locations of each loss.Several reviews of this artwork’s provenance and journey have taken place over the last few decades, each revealing new details and exploring new leads.27 Theories regarding what happened to the painting and even who painted it have changed over the years, requiring a flexibility in both mindset and the mapping tool.

An object-oriented approach suited this painting and worked to decenter Nazi activities. Although it was not possible to include multiple narratives on this map, we have provided additional details about the owners throughout the narrative. The Czartoryski family owned this artwork for over two hundred years and sheltered it from danger, and it accompanied them through exile and war and during the growth of the family’s museum. The Portrait was not just a loss for the cultural heritage of Poland, but a personal loss as well. The map’s capacity for additional commentary and captions allowed information on the family to be included beyond just a name and dates of ownership. Their story is intertwined with the artwork. The software chosen to visualize this case study allowed for context and details to be added beyond simply a name, location, and date.

In the Explorer option of ArcGIS StoryMaps, there are no numbered points or lines to connect the locations. Instead, a list of the points remains on the side of the map and users can select either a particular point on the map or an item on the list to see the details. Once a point is selected, users can scroll up or down to be taken to the other points on the map. The details on the side may be displayed in either a grid or a list format. In order to accommodate for the narrative focus of this map, a list option was used and dates listed first in the title of each item, followed by a location. One benefit to this presentation is that it puts more control in the hands of the user. They are able to choose a selected point rather than navigate through a more guided set of slides and points to find a particular one.

The basemap presented a challenge as selections were limited to those available through Esri because of time restrictions. Modern borders are familiar to the average user, but being able to choose multiple base maps that corresponded with border changes throughout the journey of this piece would have been ideal. Unfortunately the software restricts designing users to one basemap and does not offer maps that can zoom down to the street level without modern borders. We chose a map with muted colors that enabled detailed zooming for each point to provide for the needs of this map. The flexibility in mapping points allowed by this software came in handy when provenance of the portrait was uncertain and could not be narrowed down more than a particular town or even a whole country. A zoomed out map showing only a town or country is then a representation of this uncertainty. It was more difficult to represent uncertainty of time. Several dates were ranges and large gaps between data points were difficult to visualize on a map. A timeline embedded into the map may have been a more successful gap visualization tool, although recording both a large location and dates within the point title allowed for unknowns to be mapped and visualized.

Although this painting has been lost for over 75 years, the Polish government is hopeful it will be returned to them in due time.28 Until that time it looms large in the cultural heritage memory of Poland and the wider art world. Numerous questions remain that will only be answered once the painting has been returned to its rightful owners. Until that day comes and this map is filled in with the rest of this painting’s story, mapping lost works will hopefully keep them in the public’s consciousness and encourage researchers to examine the gaps and the uncertainties with the hope of uncovering the fate of the lost works.

Carl Spitzweg’s Justitia (1857) – ArcGIS StoryMaps Sidecar Feature

By Nicoletta Romano

In 2020, Carl Spitzweg’s painting, Justitia, made the news when it was sold at a Munich auction, given its the irony of artwork’s name and imagery in juxtaposition with the changes in its ownership during and after World War II.29

While researching the painting, we realized that Justitia—depicting Lady Justice on a cracked foundation with a soldier lurking in the shadows—had a compelling story and a traceable journey worth delving into in a case study.30 The painting was subject to a forced sale (or a sale under duress) by Leo and Else Bendel in 1937 to help fund their emigration from Berlin to Vienna, and by 1945 it was recovered by the Allies among the works of art hidden in the Altaussee salt mine by the Nazis. After passing through the Munich Central Collecting Point, the painting was then “returned” to the German government, as opposed to the Bendels, and subsequently hung in the official residence of the Federal President from 1961 to the early 2000s. In 2019, the painting was restituted to the Bendels’ heirs, concluding this saga and assuring that justice finally be served.

In trying to understand, follow and sketch out the route that Justitia took, we utilized a variety of provenance sources consisting of both data strings in online databases and stories in traditional scholarship—fitting for a digital humanities project. With the discovery that the National Archives as well as the Deutsches Historisches Museum’s Datenbank zum “Central Collecting Point München” had digitized records, such as the index cards when objects passed through these Allied Central Collecting Points, it seemed logical to include these archival images to accompany the painting’s journey on the map.

Since this case study revolves around one work of art, this project allowed us to focus on every point along the journey and better elaborate the narrative details. Here, one of the comments received during the initial round of user study, that more information about the artwork and visuals were helpful, was influential in inspiring additional art historical research in the form of panels on the map featuring images and captions. As a result, one of the goals of the map became about representing either a comprehensive enough case study for the user, or at least a jumping off point for future research if necessary.

Another reflection from the feedback, besides the quantity of information, that influenced the design was the need for color and detail in the map itself. When looking into tools, we opted to use Esri’s ArcGIS StoryMaps as the overall platform, and experimented with using the “sidecar function” for the map because it seemed easy to use and customize. The “charted territory” map was chosen as the basemap since it incorporates the most color of the standard basemaps in the gallery, especially in differentiating countries accordingly, compared to the default monotone “canvas” maps. This basemap also changes when zooming in, which further highlights the stark differences in locations throughout Justitia’s journey, as it shifts between a road map to navigate the cityscape of Munich, where the painting often returned, and a topographic map, when the painting was stored in the Austrian salt mine surrounded by mountains. In our public Pratt presentation, a valid critique of the basemap emerged in terms of the modern political borders that it features, and remains an important consideration. In the case of future continuation of this project or a new iteration of this particular map, we would explore the possibility of using a georeferenced historical map as the basemap.

Similarly, another suggestion for improvement from this presentation was the emphasis on the owners and their lives beyond the painting, as opposed to simply narrating their story. Questions were raised about how to include the trajectories of the Bendels on the map, so that their journey could be connected with that of Justitia. However, since there is no way to add layers in the “express map” created in the “sidecar” model, the Bendels’ points would have appeared together with those of the paintings in a confusing and perhaps overwhelming cluster. We also thought about inserting the painting’s previous travels and exhibitions across Europe, before it entered the Bendels’ collection, but encountered the same issue of cartographic representation. Though these components are not included in the present provenance map, incorporating the owners appropriately remains at the forefront of the project. For now, attempts were made to address the importance of the couple and the very human element of this story—as well as the intertwinement of these journeys and stories—by integrating them in parallel timelines within the story map.

Seeing as provenance for our project is not only about location and mapping space, but also about accounting for changes in ownership by dates, particularly those framed within a specific period, the aim of these timelines is also to show the simultaneity of Justitia’s and the Bendels’ journeys as well as the extensive length of time it has taken for restitution to occur. For us, learning about the Bendels and mapping this painting’s journey was not only about following the trail of and to justice, but also making sure to do them justice in this interpretative representation of these narratives.

Reflections

In developing these case studies, we have attempted to bring tools of mapping and narrative to bear on particular stories of Nazi-looted artworks. We hope these cases can serve as examples for representing other stolen artworks, including those beyond the places and times represented in this study—there are many acts of cultural plunder found throughout the histories of colonialism and its present manifestations. To this end, we offer several next steps and provocations for those working with data about looted artworks and those responsible for that data:

- Expanding available provenance data, particularly structured data with times, places, and named entities describing owners

- Recognizing the power interests at play in provenance data, including the lack of such data

- Approaching absences and ambiguities of provenance data as invitations for speculative inquiry, including possibilities of looting, theft, coerced sale, and more

- Holding restitution and repatriation as goals for provenance research and provenance data use in general

- Considering the roles of narrative and storytelling in making historical information accessible for broader audiences

- Centering the previous owners of looted artworks, the communities for which those artworks have significance, and the importance of the artworks themselves—as opposed to the acts of looting, destruction, and their perpetrators

- Experimenting with digital tools and offering examples which others can copy, modify, and adapt for new purposes and contexts

- Employing user research to guide the development of digital tools, and from their earliest stages31

- Building interfaces for expansion, iteration, and unanticipated future uses

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank a number of individuals whose guidance and feedback have proved invaluable to this project, including Can Sucuoglu, Interim Director of the Spatial Analysis and Visualization Initiative at Pratt Institute; participants in our user research; Carol Choi, Rachel Daniell, Nick Dease, John Decker, Micah Langer, Karyn Zieve, and other attendees at our work-in-progress presentation to the Pratt Institute community on November 17, 2021; and staff in Pratt Communications & Marketing, including Allison Meier and Jolene Travis.

Notes

- Judith H. Dobrzynski, “The Zealous Collector – A special report: A Singular Passion for Amassing Art, One Way or Another,” New York Times (New York, NY), December 24, 1997, https://www.nytimes.com/1997/12/24/arts/zealous-collector-special-report-singular-passion-for-amassing-art-one-way.html.

- Marisa Carroll, “The Painting That Launched a Thousand Lawsuits,” Hyperallergic, May 23, 2021, https://hyperallergic.com/51575/andrew-shea-portrait-of-wally/.

- Lynn Nichols, The Rape of Europa (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 6.

- Fleckner, Uwe, “Marketing the Defamed: On the Contradictory Use of Provenances in the Third Reich,” in Provenance: An Alternative History of Art (Los Angeles, Calif: Getty Research Institute, 2013), 142.

- Nichols, The Rape of Europa, 18.

- Nichols, The Rape of Europa, 23.

- Donald E. Collins and Herbert P. Rothfeder, “The Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg and the Looting of Jewish and Masonic Libraries during World War II,” The Journal of Library History 18, no.1 (1983): 26, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25541351

- Nichols, The Rape of Europa, 3–5.

- Mary-Margaret Goggin, “‘Decent’ vs. ‘Degenerative’ Art: The National Socialist Case,” Art Journal 50, no.4 (1991): 89, https://doi.org/10.2307/777328.

- Sidney Zabuldoff, “At Issue: Restitution of Holocaust-Era Assets: Promises and Reality,” Jewish Political Studies Review 19, no.2 (2007): 4, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25834718.

- Washington Conference on Holocaust Era Assets, “Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art,” U.S. Department of State, 1998, https://www.state.gov/washington-conference-principles-on-nazi-confiscated-art.

- Prague Holocaust Era Assets Conference, “2009 Terezin Declaration on Holocaust Era Assets and Related Issues,” U.S. Department of State, June 30, 2009, https://www.state.gov/prague-holocaust-era-assets-conference-terezin-declaration.

- 114th Congress, “H.R.6120 – Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act of 2016,” https://www.state.gov/washington-conference-principles-on-nazi-confiscated-art.

- Bianca Gaudenzi and Astrid Swenson, “Looted Art and Restitution in the Twentieth-Century,” Journal of Contemporary History 52, no.3 (2017): 491–518, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009417692409.

- Catherine Hickley, “She Tracked Nazi-Looted Art. She Quit When No One Returned It,” The New York Times, March 17, 2020, sec. Arts, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/17/arts/design/georg-schafer-museum-nazi-looted-art.html.

- American Alliance of Museums, “Recommended Procedures for Providing Information to the Public about Objects Transferred in Europe during the Nazi Era,” 2013, https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/nepip-recommended-procedures.pdf.

- Tracey Berg-Fulton, et al. “Art Tracks: Visualizing the Stories and Lifespan of an Artwork,” 2015, https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/art-tracks-visualizing-the-stories-and-lifespan-of-an-artwork.

- Robert Roth, “Cartographic Design as Visual Storytelling: Synthesis and Review of Map-Based Narratives, Genres, and Tropes,” The Cartographic Journal 58, no.1 (2020): 85, https://doi.org/10.1080/00087041.2019.1633103.

- Roth, 104.

- Jodi Cranston, “Mapping Paintings, or How to Breathe Life Into Provenance,” in The Routledge Companion to Digital Humanities and Art History (Routledge, 2020).

- Chung, Timothy. “Case Review: Cassirer v. Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation.” Center for Art Law, December 5, 2019. https://itsartlaw.org/2019/06/12/case-review-cassirer-v-thyssen-bornemisza-collection-foundation/.

- “Lasar Segall Processes – Museu Lasar Segall,” Google Arts & Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/lasar-segall-processes/5gJyDOgp0pt5Lg.

- Kaira M. Cabañas, “Lasar Segall,” Artforum, Summer 2018, https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201806/lasar-segall-75607.

- Julia Pacewicz, “Raphael’s Still Missing ‘Portrait of a Youth,’ Case Study: Provenance Series (Part IV),” Art & IP Law Blog, Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, April 22 2020, https://www.artandiplawfirm.com/provenance-series-raphaels-still-missing-portrait-of-a-youth-case-study-part-iv/.

- Julia Michalska, “Poland’s long-lost Raphael found,” The Art Newspaper, August 2, 2021 (accessed via Wayback Machine), https://web.archive.org/web/20120804031516/http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Poland%27s-long-lost-Raphael-found/26991/. Martyna Norwicka, “Muzeum Narodowe odnalazło zaginiony obraz Rafaela? “W prywatnej kolekcji”, wyborcza.pl, updated December 30 2016, https://krakow.wyborcza.pl/krakow/7,44425,21185613,muzeum-narodowe-odnalazlo-zaginiony-obraz-rafaela-w-prywatnej.html?disableRedirects=true.

- “Portrait of a Young Man”, War Losses Catalog, Department for the Restitution of Cultural Goods, http://dzielautracone.gov.pl/katalog-strat-wojennych/obiekt/?obid=3095.

- Janusz Walek, “The Czartoryski “Portrait of a Youth” by Raphael”, Artibus et Historiae 12, no.24 (1991): 201–224, https://doi.org/10.2307/1483421. Jozef Grabski, “The Lost “Portrait of a Young Man” (Attributed to Raphael) from the Collection of the Princes Czartoryski Family in Cracow. A Contribution to Studies on the Typology of the Renaissance Portrait”, Artibus et Historiae 25, no.50 (2004): 215–239, https://doi.org/10.2307/1483795.

- Martyna Norwicka, “Muzeum Narodowe odnalazło zaginiony obraz Rafaela? “W prywatnej kolekcji,” Wyborcza.pl, December 30, 2016, https://krakow.wyborcza.pl/krakow/7,44425,21185613,muzeum-narodowe-odnalazlo-zaginiony-obraz-rafaela-w-prywatnej.html?disableRedirects=true.

- Kate Brown, “The Nazis Wanted to Put This Painting in a Museum Dedicated to Hitler. Now It’s the Star Lot of One of the First Live Auctions Since Lockdown,” Artnet News, May 6, 2020, https://news.artnet.com/market/neumeister-carl-spitzweg-1852731.

- Monika Tatzkow, “Justitia In Jewish Ownership: Leo Bendel,” in Justiz-Wesen Carl Spitzweg “Das Auge des Gesetzes (Justitia),” ed. Katrin Stoll (Munich: Neumeister Münchener Kunstauktionshaus, 2020), pp. 40–54.

- Fred Gibbs and Trevor Owens, “Building Better Digital Humanities Tools: Toward Broader Audiences and User-Centered Designs,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 6, no.2 (2012), http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/6/2/000136/000136.html