At the beginning of October, I used my New York Public Library card to pay a visit to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). The enormous complex was packed on that sunny Saturday afternoon, but I was still able to deeply engage with the exhibits.

AMNH was the 12th most-visited museum in the world in 2017, having almost 5,000,000 people come through its doors throughout the year (TEA/AECOM, p. 19). The institution holds 34,120,652 specimens and artifacts in its collections, and recently added over 44,000 more (American Museum of Natural History Annual Report, p. 4).

The public spaces of the buildings that make up the institution are segmented into 4 floors and a lower level. Upon entering, visitors are given a physical map outlining the best paths to take depending on the order in which they’d like to see the exhibits. AMNH also offers a mobile app that gives “turn-by-turn directions”, provides descriptions of exhibits, and allows for the use of augmented reality and other digital experiences that can open up more levels of engagement throughout (Figure 1).

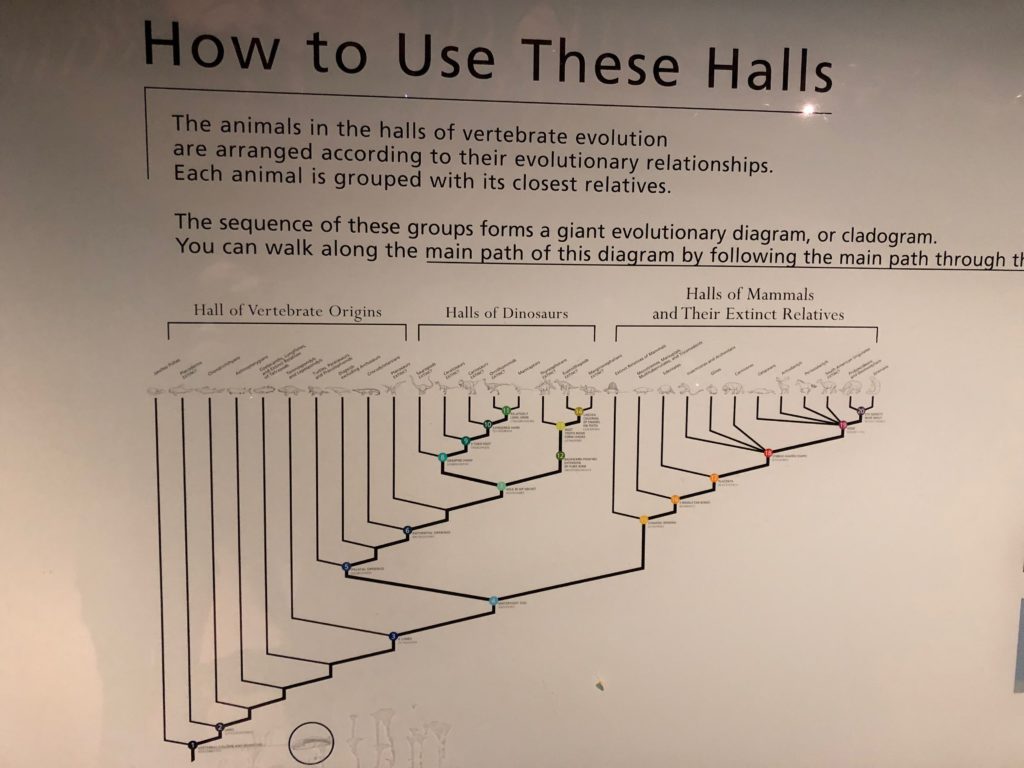

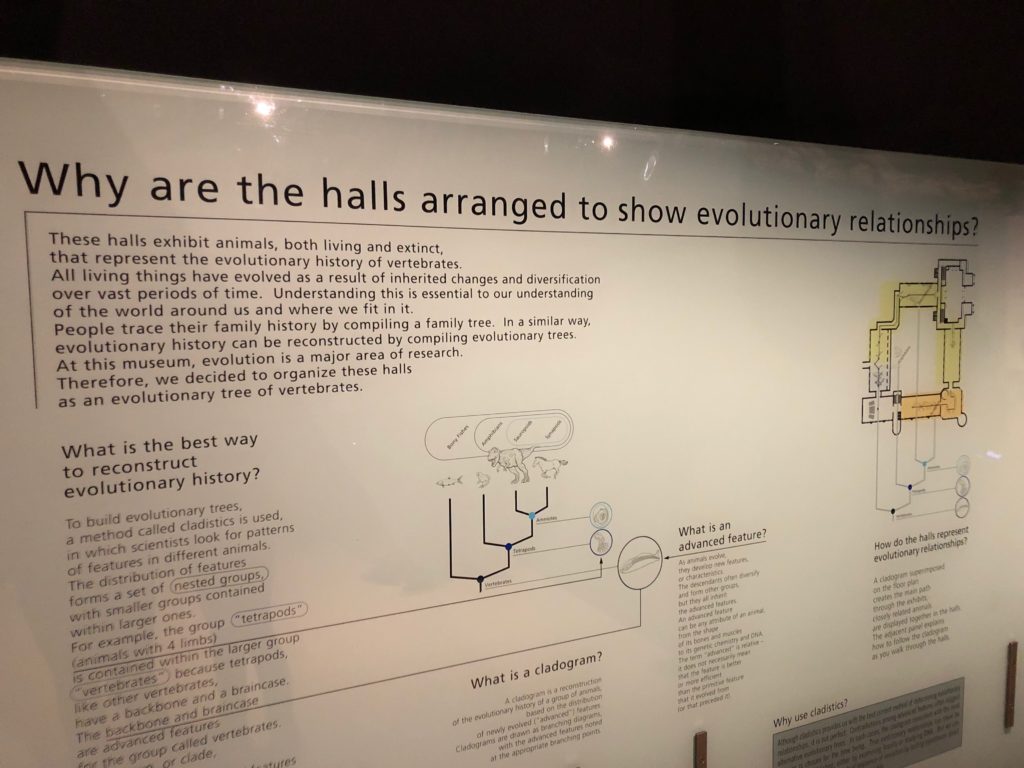

A very notable way in which AMNH creates a logical navigation of the space is through a mixture of information visualization and mapping. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show some charts for The Hall of Vertebrate Origins, in which a cladogram is used to physically arrange exhibits throughout the Hall in order of evolutionary relationship.

This technique melds the information on display with the physical space in order to help visitors navigate. Other visual techniques are also used, like the display in Figure 4 that makes up for missing parts of a fossil in order to show what the complete specimen might look like.

As mentioned, the museum also has the ability to use augmented reality, permitting interaction with the exhibit itself and enabling the experience to not just rely on a visitor’s ability to read as they browse collections (Robinson, 2015, p. 4). Signifiers are placed on the floor throughout to signal when this function is available (Figure 5).

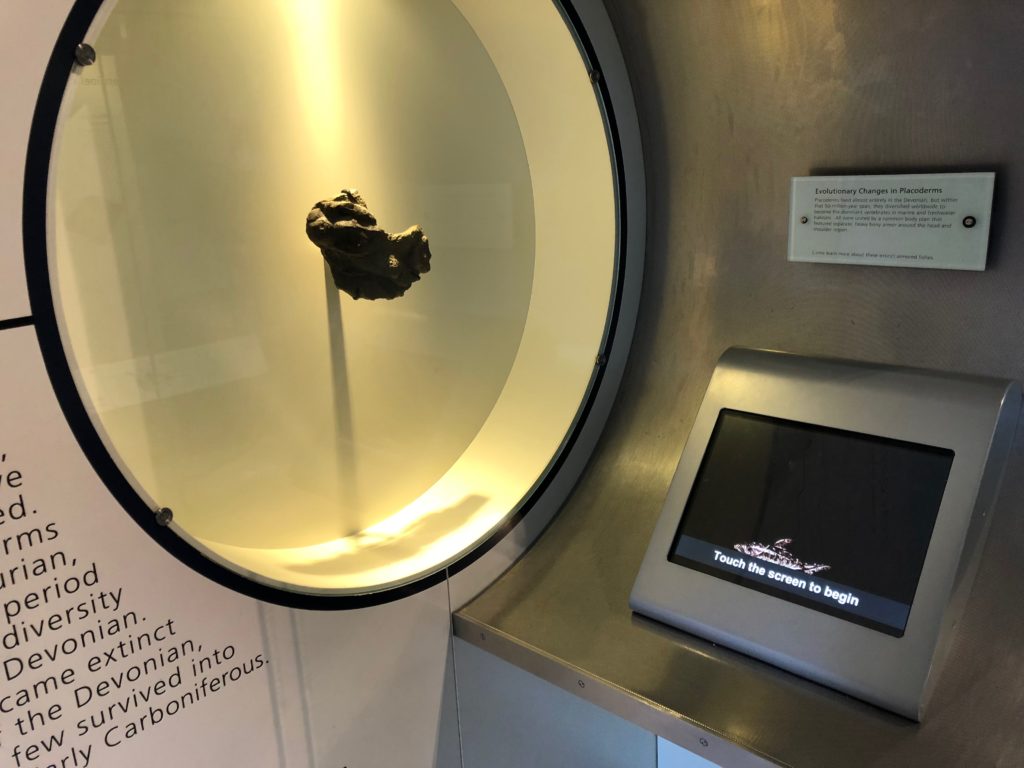

AMNH also uses tactile methods for visitors to engage on a more active level by embedding multi-sensory interactions into the exhibits themselves. Figure 6 shows a touchscreen that teaches more about “Evolutionary Changes in Placoderms” by providing the option to interact with a device rather than just merely showing a description on a sign.

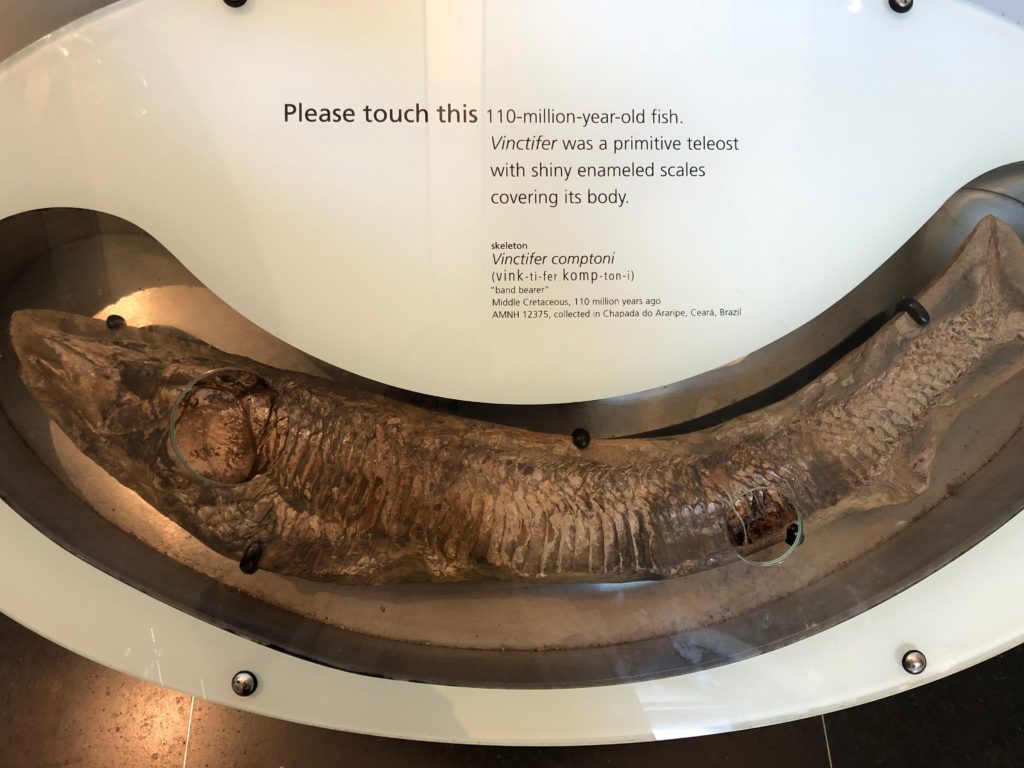

In Figure 7, a sign says “Please touch this”, a very obvious signifier telling visitors that they can literally touch the bony scales of a Vinctifer, a fish that swam in the ocean 110 million years ago.

The world’s largest meteorite on display, The Cape York Meteorite (Figure 8), lets visitors experience “touching an object that is nearly as old as the Sun” (American Museum of Natural History– Ahnighito).

Using the sense of touch fits into Robinson’s idea of using multi-sensory options when interacting with a display in order to make exhibits more participatory (Robinson, 2015, p. 5).

Established in 1869, the American Museum of Natural History is a scientific juggernaut, a leader in exploration and research, and is constantly adapting to the new ways in which people can experience and enjoy museums.

References

- TEA/AECOM 2017 Theme Index and Museum Index: The Global Attractions Attendance Report. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.aecom.com/content/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2017-Theme-Museum-Index.pdf

- American Museum of Natural History Annual Report 2017. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/document/382887896/AMNH-Annual-Report-2017#fullscreen&from_embed

- Robinson, L. (2014). Multi-sensory, Pervasive, Immersive: towards a new generation of documents. Retrieved from Centre for Information Science – City University London: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/6864/1/LR%20-%20Immersive%201.pdf

- American Museum of Natural History – Ahnighito. Retrieved from https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/permanent-exhibitions/earth-and-planetary-sciences-halls/arthur-ross-hall-of-meteorites/meteorites/ahnighito