Person: Heidi Cooley

My person is Heidi Cooley, author of Finding Augusta: Habits of Mobility and Governance in the Digital Era. I was at the 4th floor library at PMC looking at the new books display, and this book caught my attention. The title and the cover image conveyed the perfect combination of artsy, academic, and applying theory to practice. A brief skim of the chapters revealed that this book encapsulates perfectly the four degrees taught at the School of Information.

So what is Augusta? Scott Nixon, a traveling insurance agent from Augusta, Georgia, used a 16mm camera to document places in the U.S. called Augusta, filming from about 1930 to 1950. These are towns and streets and villages and storefronts and some other surprising Augustas. The result is an 18-minute movie, available on YouTube and archived, along with Nixon’s home movies, at the University of South Carolina (USC).

Cooley was a professor of technology and media arts at USC, and during a visit to the archive, the archivist showed her The Augustas and these 18 minutes triggered this book. The book is interesting, clever, and well written, but the main appeal to me is how Cooley extrapolated meanings and applications of information in ways that are both deep and broad and directly connect to our school. The Augustas relate to technology, mobility, mobile devices, bodies in motion, managing the movement of “stuff,” the application of surveillance, tracking, indexing information, metadata creation, digital and physical preservation, archiving, display, and the implication on governance.

Cooley’s departure point is the traveling salesman problem, which asks, “Given a list of cities and the distances between each pair of cities, what is the shortest possible route that visits each city and returns to the origin city?” It’s a question that is relevant to information storage, retrieval, design, display, usability, findability, and more. Books and articles that reflect the intellectual landscape in an interdisciplinary way are few and far between, and Cooley’s study is an “example of digital humanities scholarship and critical readings of the political stakes of new media technologies” (Archibald, 2016). It can provide new appreciation for a broad and deep understanding of information.

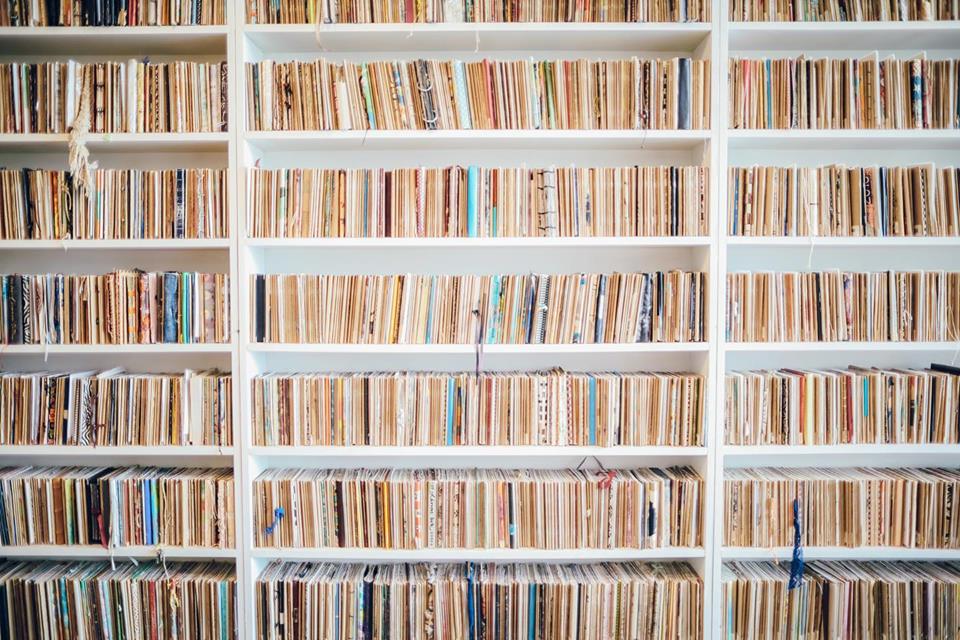

Place: Brooklyn Art Library – The Sketchbook Project

I’m not sure what possessed me to make my way across town on one of the coldest days of last winter to visit The Brooklyn Art Library. I must have read about it someplace, but I can’t recall where.

Nestled in some abandoned (or maybe it was the cold) side street in Williamsburg, the library is one large rectangular room lined with bookshelves, and on them are uniform sketchbooks. People buy a sketchbook from the library, then draw, paint, write, collage to their hearts’ delight, and bring or mail it back to the library. The library digitizes the books, adds metadata, and places them on the shelves where they are arranged chronologically. To look at a book, you register on your phone or using one of their iPads, and request up to three sketchbooks. You can search by artists, by title, by region, by topic, and more. You receive the book within a few minutes and as a special bonus receive the book immediately preceding the one you requested. This aspect of the arrangement particularly appealed to my knowledge organization sensibility. It somehow reminded my of Aby Warburg’s library in London and its cross-disciplinary references between adjacent sections.

The books themselves are, as one might expect, very wide ranging. Every imaginable kind and color of ink and pencil and paint and every style of drawing. There are journals and landscapes and manga and books in all languages and from many countries. Some are magnificent, some are puzzling, but the effect is quite strong, and even the duller ones are lifted up by being part of a beautiful and surprising collection.

Toward the back of the library there is a community-style conference table where visitors can look at the books. There were few people during my visit (temperatures were in their 20s, after all) but there were some, two adults and a child, some other adults of all ages. The people who work there are conversational without being pushy and will take their cues from the visitor.

The library embodies some of the ideas expressed in Finding Augusta, particularly those about arrangement of information as mobile objects; as Cooley notes, “mobility, its organization and potentiality, is the defining problem of this present” (Cooley, 2014). To that end, the Brooklyn Art Library provides its Bookmobile, which brings the collection to locations around the country in a mobile library.

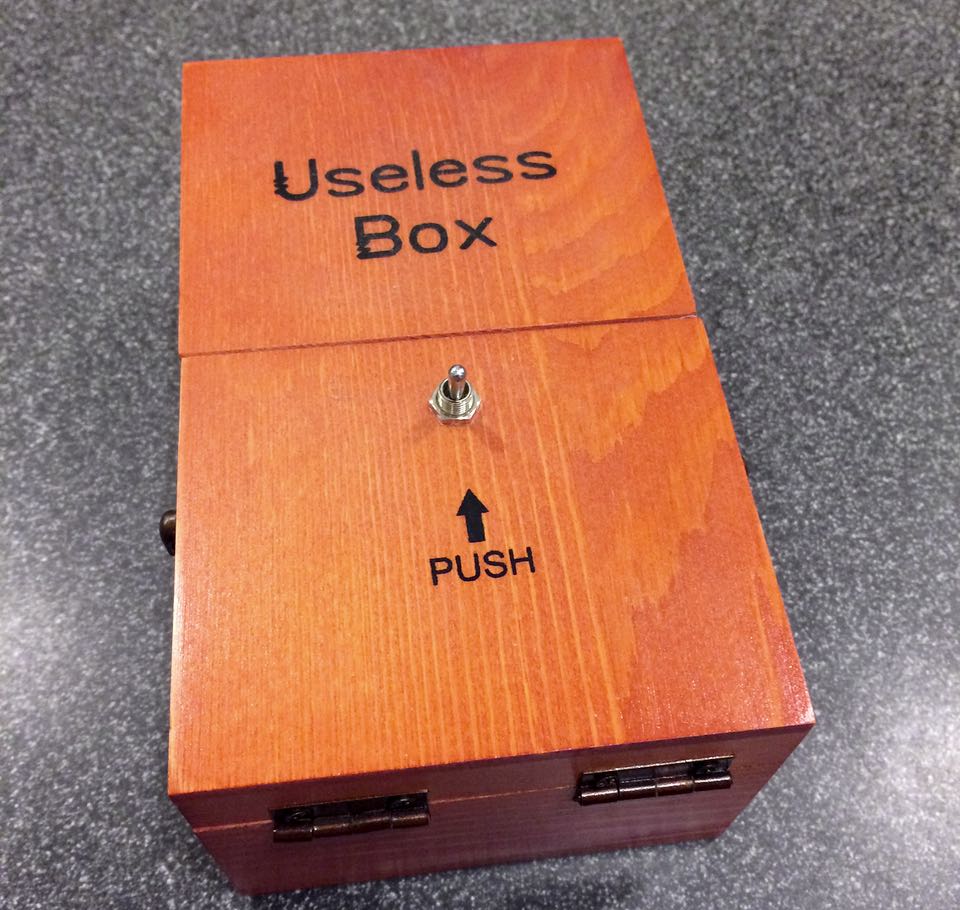

Thing: The Useless Box

For my Thing, I chose a useless box. How do I know it’s a useless box? Well, it says so in bold black lettering on top of a flimsy looking plywood box: Useless Box.

Right under the lettering there is a slit in the cover, and below it, a simple mechanical switch. Push the switch and half cover lift open from the hinge to the center, only to immediately close again. Open close, open close—that’s all it does. Useless.

Measuring about six inches, I can hold it my hand, turn it around and examine it. Peeking inside I can see a small mechanical device operated by battery. Pushing the outside switch makes the top open and immediately close. The only use that comes to mind, or at least to my mind, it that this is some executive stress toy.

So what makes The Useless Box a worthy choice for my information-Thing? Well, it’s the legacy of the Useless Box that ties in to our information universe. Developed in the 1950s in Bell Labs, it is the brainchild of Claude Shannon, a pioneering information theorist:

“The first working model was constructed by his mentor, Claude Shannon, who later became known as the father of information theory. This context, the fact that the creators of this aggressively pointless gadget are emblematic figures in the ascendancy of machines over our contemporary world, lends a frisson of historical oddity to what is essentially an executive toy.”

(O’Connell, 2016)

Contemplating the box as an expression of meaning is an act of mediation that can take you in many directions, from the meaning of labor and mechanical objects to questioning usefulness itself. And finally I admit, one appealing thing about this Thing is that is reminds me of Thing. Picking up on some lines of thought from Cooley, this can take us to the latest in creating life out of dead brain tissue to Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” in which a woman learns how to see the future:

“From the beginning I knew my destination, and I chose my route accordingly. But am I working toward an extreme of joy, or of pain? Will I achieve a minimum, or a maximum?”

(Chiang, 2002)

In other words, even when everything is known (like a device that you know will close itself immediately after you open it), isn’t it still possible for wonder to exist?

by Debbie Rabina, Ph.D.

References

Archibald, R. (2016). Review of Cooley, Heidi Rae, Finding Augusta: Habits of mobility and governance in the digital era. H-War, H-Net Reviews. Retrieved from http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=43095

Chiang, T. (2002). Stories of your life and others. New York: Vintage.

Cooley, H. R. (2014). Finding Augusta: Habits of mobility and governance in the digital era. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press.

O’Connell, M. (2016) Letter of recommendation: The useless machine. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/04/magazine/letter-of-recommendation-the-useless-machine.html

Shaer, M. (2019). Scientists are giving dead brains new life. What could go wrong? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/02/magazine/dead-pig-brains-reanimation.htm