Person: Cynthia Cruz

Cynthia Cruz is a poet of German and Mexican descent, born in Germany but raised in northern California. Her work reads like a scrapbook, image after image placed on top of one another. Her third book Wunderkammer translates to “a cabinet of curiosities”. Each poem heavy with German history, German artists, and fragments of the personal. Each image is locked in a multi-leveled vitrine for the reader’s consumption. The poet’s mother was a hoarder, the poet is obsessed with archiving, the need to “collect, assemble, and name”.

In 2018 I attended Cynthia Cruz’s craft talk at the Poet’s House entitled “The Archive as Resistance”. In 2010, as a Hodder fellow at Princeton, Cruz scoured through archives to research for Wunderkammer. She drew inspiration from German visual artists: Hanna Darboven, Gerard Rictor, and Rosemary Trockel. As well as great German writer and thinkers Aby Warburg and Walter Benjamin. Throughout her collection, she created “totems and objects that carry memory or meaning”. She describes the poems in Wunderkammer as dense, long lines, and no space, a type of claustrophobia”.

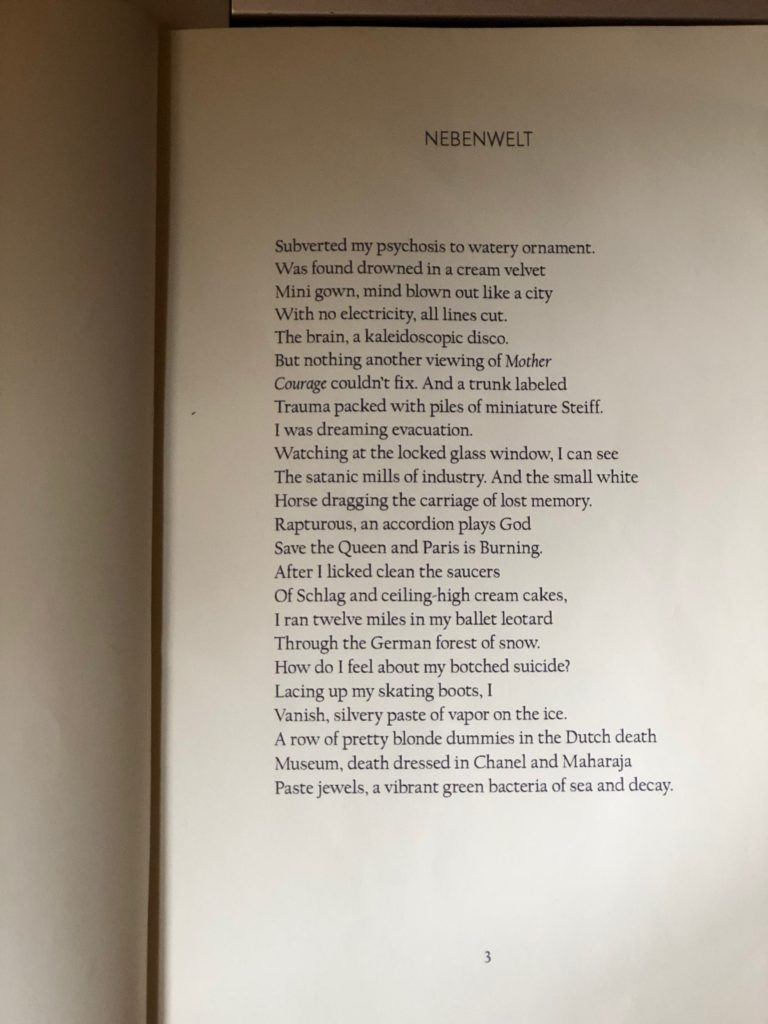

taken from Cruz’s Wunderkammer

Wunderkammer is an exploration of trauma and how trauma informs and changes people. A part of her research involved reading about the building of the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

The creation of a museum that houses artifacts and relics of Berlin Jews chronologically create a sense of closure as if the Holocaust was now in the past. When in fact that past has not passed. Questions of how it could have happened and it’s impact are felt throughout and informs contemporary Germany, Berlin, and the world.

In conversation with Sharon Macdonald’s “Is Difficult Heritage Still Difficult?”, Cruz’s work remains personal (fictional or not), her use of German history is through her lens (girlhood, failure, and mental illness). Macdonald’s piece deals with the right way to present such a dark past: facts versus emotions, how much of the horror to show, heritage versus nationalism, and etc. Through the poems in Wunderkammer, Cynthia Cruz takes fragments of her past, her mixed cultures and works from people from her native country to make a sort of collage.

Place: The Historic New Orleans Collection

In 1938, General L Kemper and Leila Williams purchased two properties in the French Quarter—The Merieult House and a late 19th century residence on Toulouse Street. Throughout their lives they gathered a hefty amount of important Louisiana artifacts. After the couple passed, their home became the Historic New Orleans Collection.

In 2016, during my first trip to New Orleans, I got to witness the award winning and traveling Purchased Lives: The American Slave Trade from 1808 to 1865 exhibit at the Historic New Orleans Collection. I walked in with two childhood friends and my one friend’s aunt, we moved separately, sometimes we regrouped but we never spoke. From what I recall, you could hear a pin drop, it seemed like every visitor was busy absorbing the information to say anything of value.

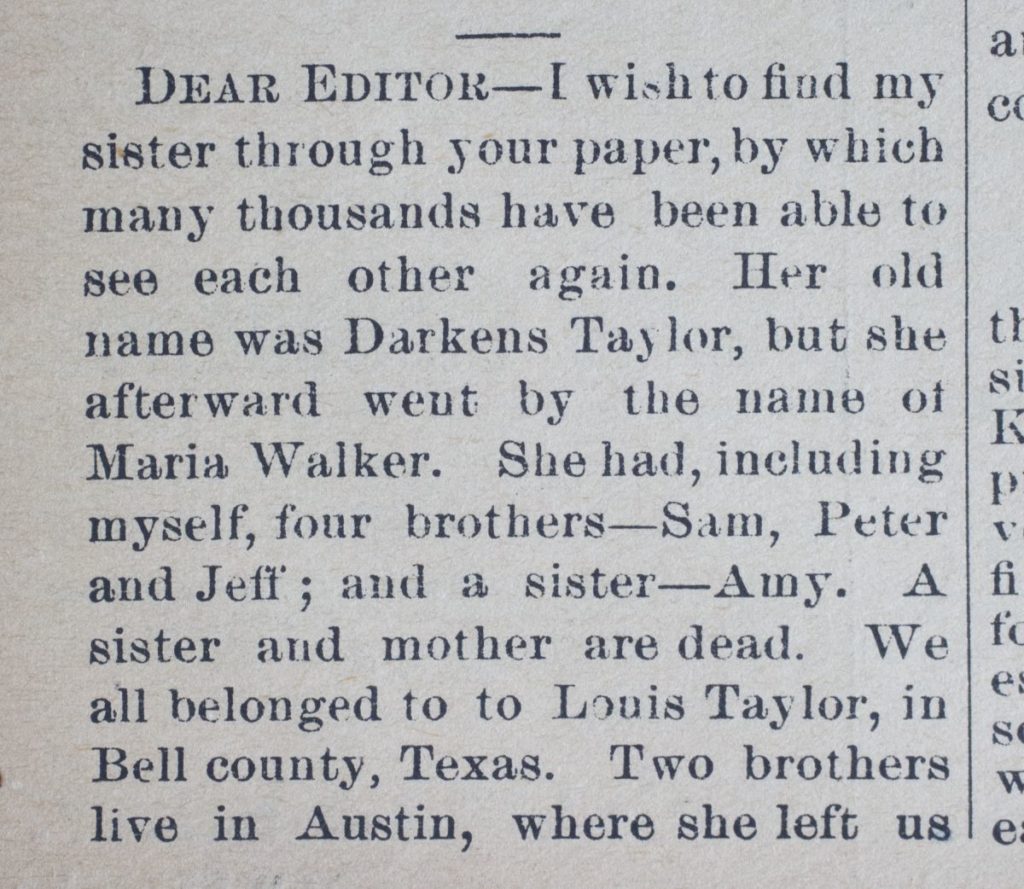

Historian Erin M. Greenwald curated the exhibit which includes period broadsides, paintings, and prints illustrating the domestic slave trade, interactive displays, historical records by tracking the shipment of more than 70,000 people to New Orleans. While there were interactive components, most affective, was the “Lost Friends” ads placed after the Civil War by newly freed people attempting to locate family members. The preservation of those ads made everything so three dimensional. In Cloonan’s “W(H)ITHER Preservation”, she writes, Preservation allows for the continuity of the past with the present and the future”. I was there on vacation, steps away from Bourbon street, filled with tourists and bachelorette parties, but on a ground drenched in history and blood. The presentation of the ads-from floor to ceiling- daughters looking for mothers they had not seen in 30 years, gave the memory institution have a pulse.

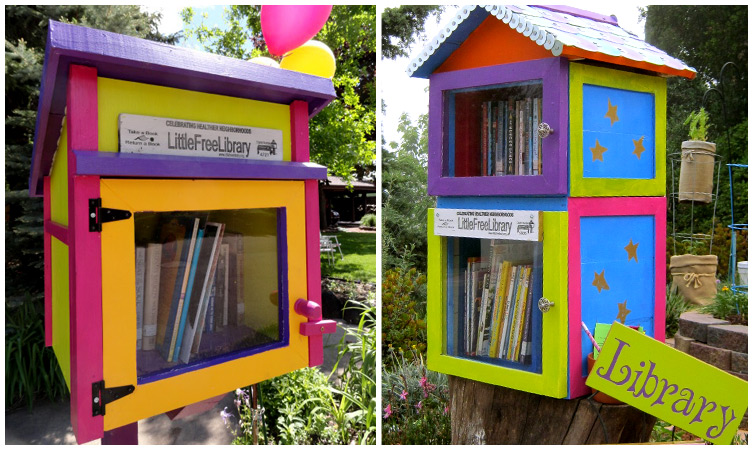

Thing: Little Free Library (Take A Book, Share A Book)

A small wooden box full of books, where neighbors are encouraged to take a book and leave a book. Little Free Library is a non-profit whose mission is to increase access to books for readers of all ages and backgrounds. The organization boasts 90,000 street libraries in 90 countries. Those who want to start a Little Free Library can order a kit through their website or build their own. Their website also has a map where the user can type in their zip code and find the Little Free Library nearest to them. There are two in walking distance from my apartment in Bushwick. I think the idea is adorable and promotes community building.

This reminds me of Chatman’s four concepts in “The Impoverished Life-World of Outsiders”. She names deception, risk-taking, secrecy, and situational relevancy as reasons “information outsiders” remain on the outside. But with something like the Little Free Library, it’s open to everyone, there need not be any sharing of personal information or personal stories. There is a freedom, no need to sign up for a library card, or fees for lateness, it is almost encouraged for it to be anonymous. The only concern is not enough people knowing about such a uniting program.

-Herbert Duran

Resources

2018: The Archive as Resistance: A Craft Talk with Cynthia Cruz. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2019, from Poets House website: https://poetshouse.org/audio/2018-the-archive-as-resistance-a-craft-talk-with-cynthia-cruz/

Chatman, E. A. (n.d.). The Impoverished Life-World of Outsiders. 15.

Chatman—The Impoverished Life-World of Outsiders.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/924614/mod_resource/content/1/Chatham-Information%20Povertyt.pdf

Cloonan, M. V. (2001). W(H)ITHER Preservation? The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 71(2), 231–242.

Cloonan—2001—W(H)ITHER Preservation.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/924550/mod_resource/content/1/Cloonan_2004.pdf

Cruz, C. (2014). Wunderkammer. New York: Four Way Books.

Exhibition – Purchased Lives: New Orleans And The Domestic Slave Trade, 18081865 – New Orleans, LA. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2019, from http://www.americantowns.com/news/exhibition-purchased-lives-new-orleans-and-the-domestic-slave-trade-1808aeur1865-22900958-new-orleans-la.html

Macdonald, S. (2015). Is ‘Difficult Heritage’ Still ‘Difficult’?: Why Public Acknowledgment of Past Perpetration May No Longer Be So Unsettling to Collective Identities. Museum International, 67(1–4), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/muse.12078

Macdonald—2015—Is ‘Difficult Heritage’ Still ‘Difficult’ Why Pu.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://lms.pratt.edu/pluginfile.php/924553/mod_resource/content/1/MacDonald_2015.pdf

Purchased Lives Exhibit Opens At The National Civil Rights Museum. (2018, January 25). Retrieved November 7, 2019, from Black Then website: blackthen.com/purchased-lives-exhibit-opens-national-civil-rights-museum/

What We Do. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2019, from Street Books website: http://streetbooks.org/what-we-do-1