The Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, located on Fifth Avenue between Forty-Second and Fortieth Street, stands as a centerpiece for the New York Public Library. It is a grand marble building that has remained a spectacle since 1911. Few things have been changed in the library, beyond modern updates and fixes, and most people want it to stay that way. But what about what goes on inside the marble?

Are the librarians the same people that checked out the first books?

Have librarian practices remained the same?

Is information still circulated through the same stacks that were built in 1911?

Do people still use the research library?

What type of people actually participate in library offerings?

Just how old is this library?

To catch a glimpse at the answers to these questions, I spent a day observing researchers and patrons at the New York Public Library Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, as well as interviewing library staff.

Setting

I decided to spend most of my time in a smaller research room instead of the main Rose Reading Room for multiple reasons. First, tourists flock to the Rose Reading Room, and they are not the focus of my inquiries. Second, the Local History and Genealogy Milstein Division where I took up shop, allowed me to view researchers, librarians, and staff all at the same time. Third, this division of the library was broader than some of the other research rooms and as a result I would be able to observe a wider range of questions, requests, and interactions.

Observation

From the start I notice that everyone who enters the research room has one two reactions. They either straighten up and constantly check with the librarian visually to make sure they are not breaking any rules (similar to how people react to seeing a police officer), or they smile and say hello as if they feel welcomed. Both reactions indicate that librarians on title alone have a level of respect from the general public. It is for this reason that they have a certain code of ethics and an obligation to their community to keep the information in the library safe. It is also why diversity among library staff, and inclusion for all is so important in a library. As respected figures, librarians set a standard for others.

Staff & Diversity

It is not difficult to see that the New York Public Library places value on diversifying their staff. The Local History and Genealogy division (LHG) in particular represents varying races, sexes, languages, genders, ages, and sexual orientations. The library publicly puts valuable information into all types of people’s hands, which I believe is an effort to normalize the idea that information professionals can be anyone.

Interestingly, I also noticed that most of the librarians in LHG were male. In my personal experience it has often been that most librarians are women. Despite this, I noticed, unsurprisingly, that there was no change in how the librarians interacted with patrons or researchers, or how their work got done. Overall, based on the ALA Manual definition of diversity- “race, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, creed, color, religious background, national origin, language of origin or disability”, the NYPL has kept up with ethical and responsible hiring standards.

Patrons

If the librarians are the brain of the library, and the books are the lungs, the patrons are the heart. Without the people that wander the stacks looking for information, nothing would be read or investigated. The librarians would be out of job, and the books would be useless. It is for this reason that I found it interesting that not everyone has equal access to the library.

The key to everything NYPL has to offer is a library card. It is a simple plastic thing with a barcode number that can reveal a world of opportunity. Want to check out a book? Better grab your library card. What if you want to browse the internet for a bit? Got to use your library card. It seems the only thing you can do without a library card is stare out the window and enjoy the climate controlled building.

To get a library card you need two things: an address, and an ID with that address on it. For most people that come to the NYPL this isn’t an issue. Even if your ID has a different address on it, you can pull up a bill or a piece of mail with your name and place of residence on it and they’ll welcome you to the club.

For a smaller, but still very relevant group of visitors, however, having an address is not easy. According to the Coalition for the Homeless, there are 62,391 people without permanent homes in New York City. That is 62,391 people who cannot use the library to find jobs on the computer, or check out a book to develop marketable skills. This exclusion of a group of people that would benefit significantly from library services is definitely a flaw in the NYPL system.

Interview

After spending some time observing in LHG, I sat down with one of the librarians so that I could learn about the things I couldn’t see. Contrary to stereotypes, he had a demanding voice and stature and I felt compelled to listen to him.

Information Overload

One of the more important topics revolving around librarianship, in my opinion, is how these professionals handle data or information overload. Not long ago librarians often had to fight against having too little information available to them. With the internet, digitization of thousands and thousands of records and collections, as well as increased patron contributions, librarians have an overwhelming amount of resources. When asked about this, the LHG librarian explained that he had to learn how to research more effectively. Databases have helped narrow down search results, but he mostly relies on his own ability to filter out the extra stuff. He also mentioned that in the research libraries in particular, patrons use the online catalog and databases to find their own materials before bringing it to him for assistance. This means, however, that his job also now includes teaching patrons how to use the library website, its databases, catalog, and other little overly complicated bits.

With all of this new digital content and information floating along above our heads in the cloud, an important question is; Who owns it, and why do libraries have it? The librarian had a quick answer to this, which was if the library had to own everything it circulated, no one would know anything of importance. He pointed out a feature of LHG that was pretty popular with researchers; a file system of researcher-created records of families, places, and things. The library doesn’t necessarily own any of the findings in those files, but it keeps them and cares for them because it’s the library’s obligation to to do so.

Burnout

Naturally our conversation concerning piles and piles of information lead straight into my next question. Did he ever feel burnout? Was he ever tired of his job and did he ever feel like the work wasn’t worth the punishment? He had been quick to respond before, but was slower this time. Yes, he did sometimes feel the effects of burnout, but not in a way that made him feel like his work wasn’t worth it. Rather, he felt that sometimes the institution thought his contribution was less than what it was in reality, and that was the frustrating part, reasonably. I found this interesting considering I had previous overheard two librarians gossiping about how the people making important organizational decisions knew nothing about the system. The conclusion from this is that the NYPL administration may not fully consider the insight of those who work in the very trenches they are redesigning.

Politics, Neutrality & Librarianship

I managed to end my inquiry on the most difficult topic; Librarianship and neutrality. The librarian I spoke to had little trouble forming an opinion, ironically. He suggested that librarians can be neutral until there is a political or ideological thought that threatens the overall well-being of the library’s patrons or the collection. Generally, politics can’t play a part in researching a topic for someone, because that could limit what information you can give. Same goes for controversial ideas. He did mention at the end of our talk that he believes that it’s impossible to stifle your own beliefs completely, and that its the responsibility of the person to control how those beliefs come out.

Conclusion

As I learned about the ins and outs of the library during my observation and conversation, I found the answer to my biggest question. Despite being old on the outside, most of the inside of the library was young and new. The librarians were informed and up to date on the pressing matters of their profession. The staff was diverse and welcoming. The exclusion of some groups in the city needed some work, but I feel as if the library is aware of this issue and is working on solutions. Overall, the NYPL Stephen A. Schwarzman Building is blazing into 2020 as a leader of library practices.

References

Birdsall, William F. “A Political Economy of Librarianship?” Progressive Librarian, no. 18.

Cope, Jonathan. “Neoliberalism and Library & Information Science Using Karl Polanyi’s Fictitious Commodity as an Alternative to Neoliberal Conceptions of Information.” pp. 67–80.

Gehner, John. “Libraries, Low-Income People, and Social Exclusion.” Public Library Quarterly, vol. 29, 15 Mar. 2010, pp. 39–47., http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01616840903562976.

Nauratil, Marcia J. “The Alienated Librarian.” New Directions In Information Management, vol. 20, 1989.

Rosenzweig, Mark. “POLITICS AND ANTI-POLITICS IN LIBRARIANSHIP.” Progressive Librarian, no. 3, 1991.

Rosenzweig, Roy. “Scarcity or Abundance? Preserving the Past in a Digital Era.” The American Historical Review, vol. 108, no. 3, June 2003, pp. 735–762., doi:10.1086/529596.

Vinopal, Jennifer. “THE QUEST FOR DIVERSITY IN LIBRARY STAFFING: FROM AWARENESS TO ACTION.” In The Library With The Lead Pipe, 13 Jan. 2016.

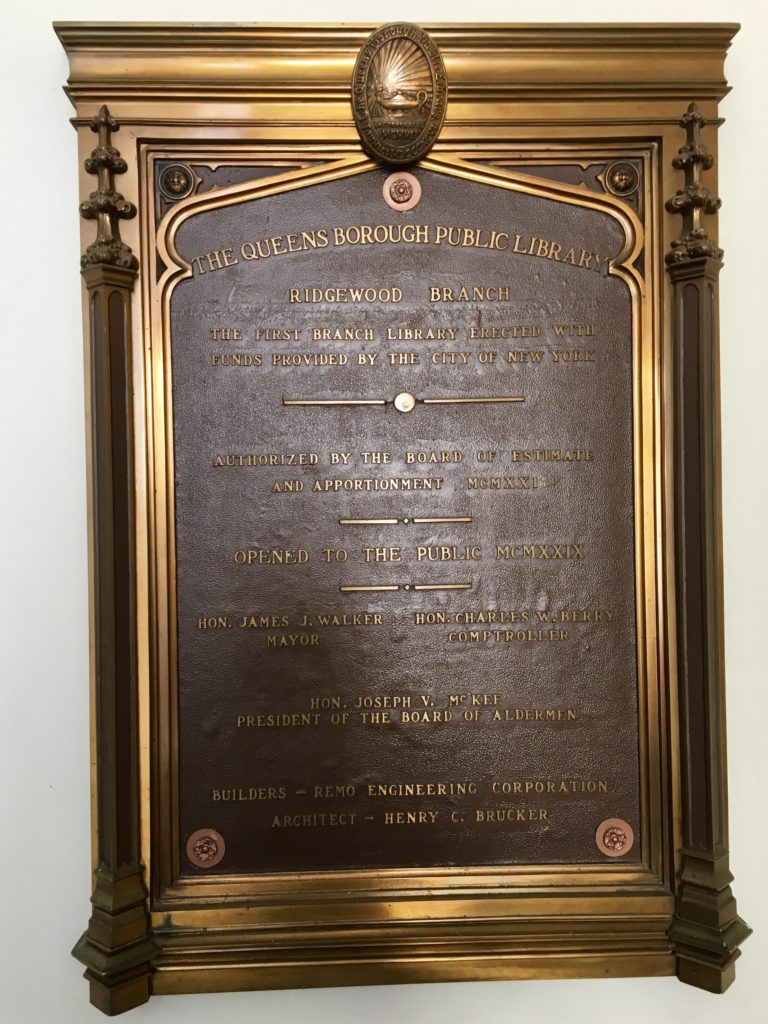

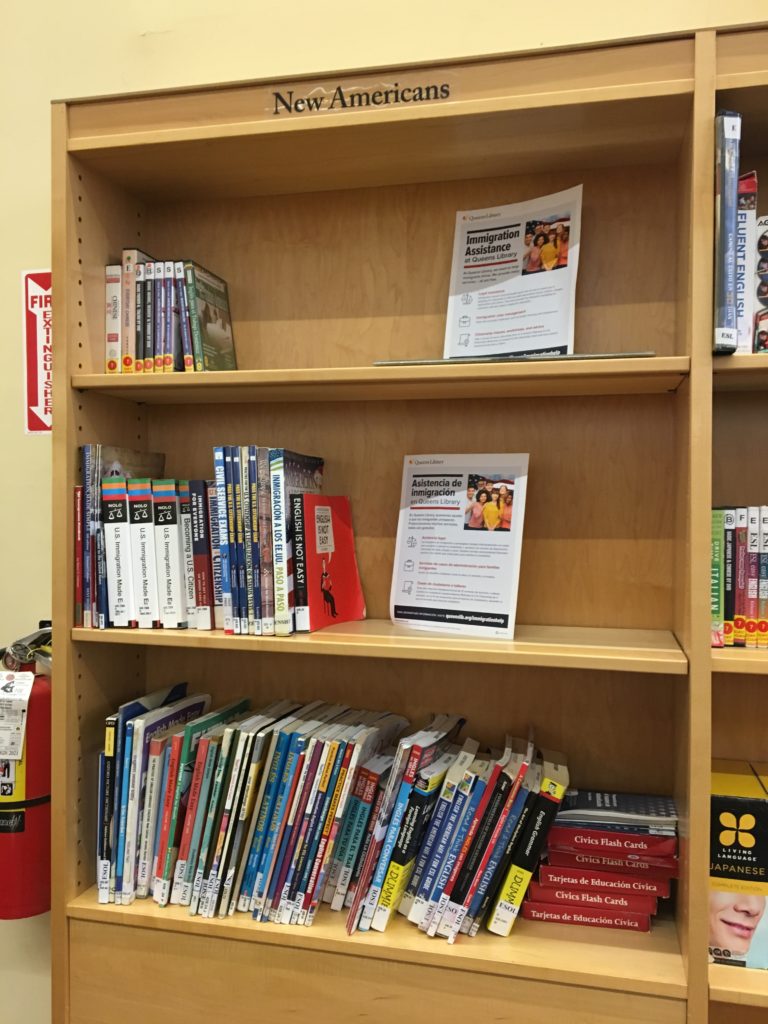

This week, I visited the Ridgewood Community Library, a branch of the Queens Library. Even though this is my neighborhood library, I had never spent time there except to pick up books I’d had transferred. The library is a fairly small branch housed in a beautiful brick building built in 1929. It was the first branch of the Queens Library to be constructed with funds from the city rather than from Andrew Carnegie. Renovated most recently in 2011, the library is fully accessible, with elevator access to every level. It is clean and well lit, with lots of natural light on the main level.

This week, I visited the Ridgewood Community Library, a branch of the Queens Library. Even though this is my neighborhood library, I had never spent time there except to pick up books I’d had transferred. The library is a fairly small branch housed in a beautiful brick building built in 1929. It was the first branch of the Queens Library to be constructed with funds from the city rather than from Andrew Carnegie. Renovated most recently in 2011, the library is fully accessible, with elevator access to every level. It is clean and well lit, with lots of natural light on the main level.