My event in review is on the NYC Media Lab Summit that I attended on September 26, 2019. Organized by the NYC Media Lab, the summit brings together people from various industries and universities in NYC to discuss the emerging technologies of today and the future. The event was split into a morning and afternoon session that was held from 8:30 AM to 5:00 PM at the New York City College of Technology (CUNY) and NYU Tandon School of Engineering.

Photo: Janet Liu 2019

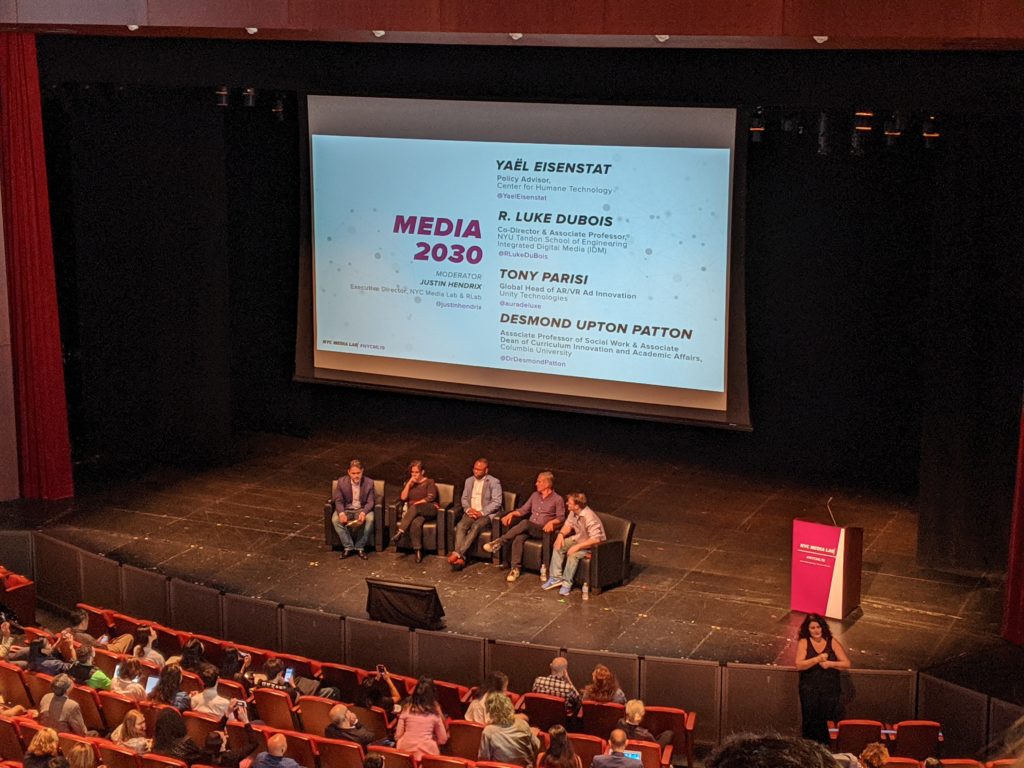

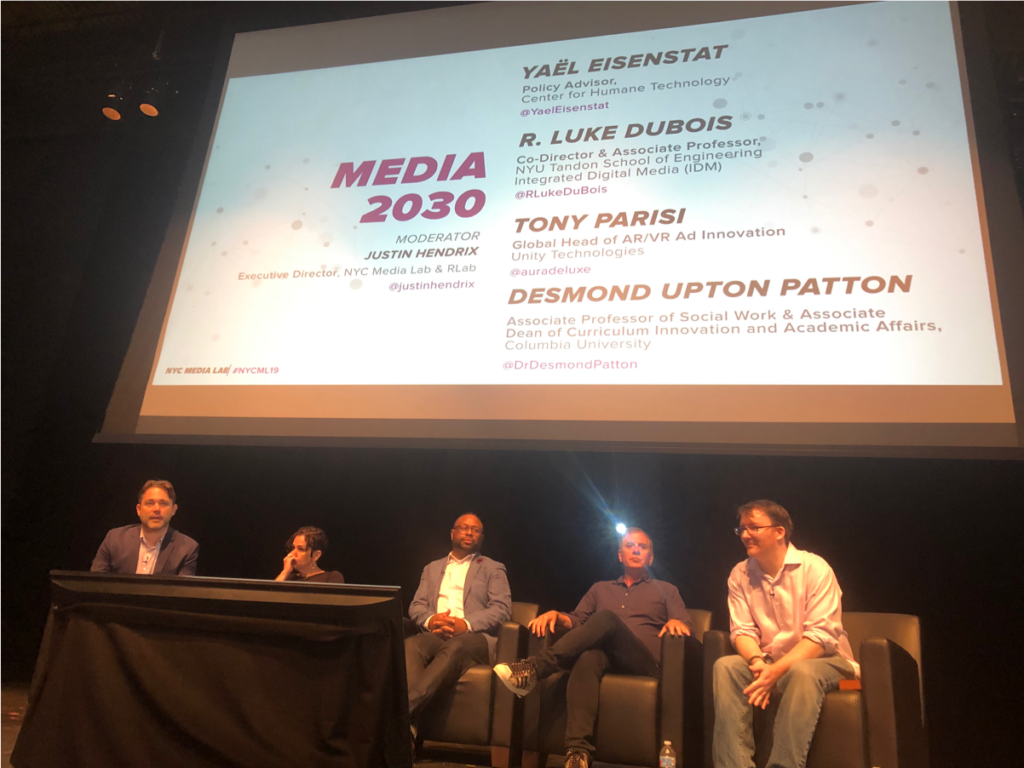

The morning session began with an innovation panel discussing the challenges and future vision for Media 2030. The list of speakers includes Yaël Eisenstat, R. Luke Duois, Desmond Upton Patton, and Tony Parisi. It was inspiring to hear different professionals’ takes on what they thought will be the most critical challenges facing institutions in 2030. Even though the speakers come from different industries, it was surprising to hear all of their responses towards AI and algorithm bias. This made me think about Posner’s discussion on the inefficiency in having a binary mindset to make sense of the world, and how binary groupings in digital humanities projects are causing further marginalization of groups (Posner, 2016). It is concerning to learn of all of the bias we have in our society today, and how it will remain a critical challenge ten years later.

Following the panel were two keynote presentations given on AI and storytelling. The first was from Amir Baradaranand, an artificial artist and art-based researcher at Columbia University. The second was from Heidi Boisvert, CEO & Founder of futurePerfect Lab and Director of Emerging Media Technology at CUNY. It was fascinating to see AI creating immersive storytelling experiences and artworks. This made me think about Norman’s argument of machines as ‘rigid, inflexible, and fixed’ (Norman, 2018). We can see these traditional views shifting, as innovators like Baradaranand and Boisvert show us a vision where artists, creatives, and AI technologies can work together. Perhaps, as Norman imagined, humans and machines will form a complementary team and take on both a human-centered and machine-centered approach to learning.

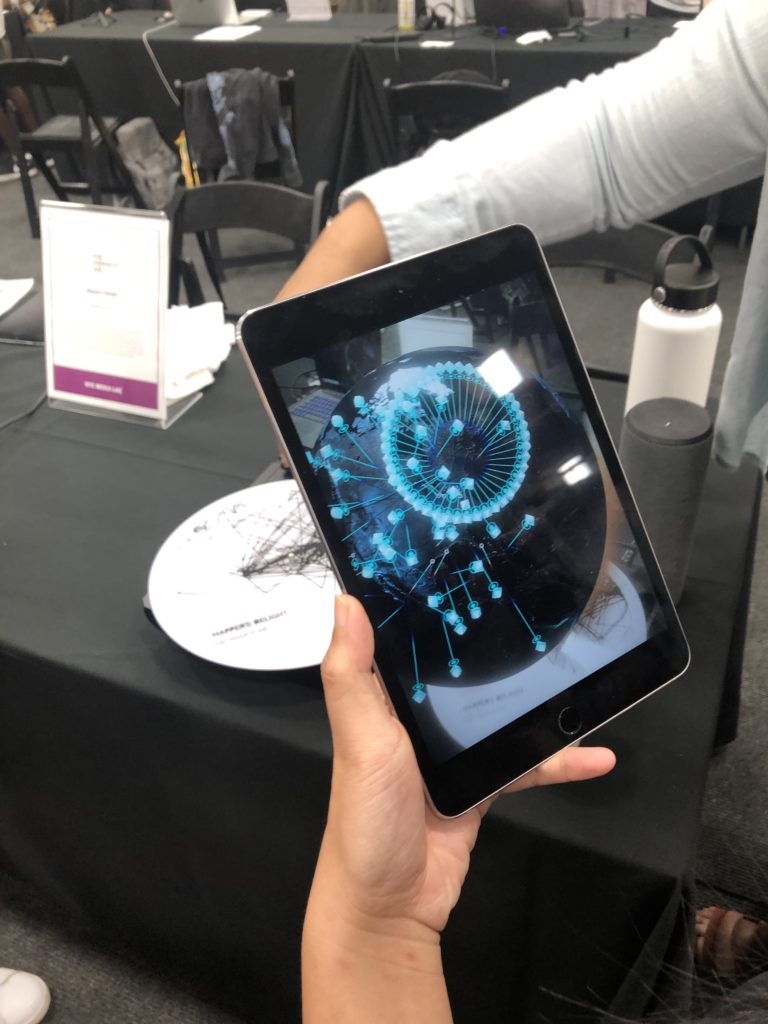

‘Mapper’s Delight’ VR expereience. Photo: Janet Liu 2019.

The afternoon session began with a Demo Expo that included 100 student prototypes. I was looking forward to this event the most as I wanted to see what kind of emerging technologies students were currently working on and excited about. It was immediately evident that there was a big trend in VR. I saw many VR products used for prototypes such as designing an online retail store, an immersive travel experience, and a chemical lab. One project that really stood out to me was the Hip Hop data visualization project, ‘Mapper’s Delight’ designed by Rap Research Lab. Instead of showing a list of lyrics, the lab explores the “global distances traveled by the lyrics contained in each rap artist’s career while exploring the secret flows of Hip-hop’s spacetime through a panoptic interface.” (“Mappers Delight VR,” 2017). It was cool and clever to see over 2,000 lyrics connected by geography and transformed into a virtual platform, which also brought an emotional engagement as I was able to find lyrics connecting me to Hong Kong. Projects like these make us think about new possible ways to provide meaning and context to big chunks of data.

Photo: Janet Liu 2019.

The last part of the summit included a hands-on workshop where attendees had the choice of picking one out of the fourteen to attend. I decided to go with Magic Leap, a leading VR company presenting on extended reality, spatial computing, and how it is transforming the industries. I wanted to attend this workshop to understand why there is such a big fascination with these types of products. Stuart Trafford, the Education Lead of Magic Leap introduced its newest product called Magic Leap One, a mixed reality product that creates immersive experiences. One point that stuck with me was when Trafford said the experience of information is changing as technology has allowed these online experiences to be personalized instead of appealing to the masses. It was fascinating to see how MR products can be applied to future industries such as in hospitals and construction sites. This workshop inspired me to write my research paper on VR and understand if there will be a demand for such a product in future museums, as I still find VR products to be very gimmicky.

Overall, I was very impressed with the structure of the summit. I expected more students to attend as tickets cost a hefty $200 but students can attend for $30. I loved the order of presentations. It started with broad topics discussing the challenges and future use of emerging technologies, to the current uses demonstrated by students, and then to workshops that show specific examples of how these types of technologies are used. Also, it is important to note that the event relied on the WHOVA conference app, which allowed you to keep track of the full agenda, learn more about sessions, take notes, chat, and most importantly, sign up for workshops. Even though the app was really convenient, it made me think about the accessibility of information. How will the experience change for people who don’t have the app downloaded and can’t sign up for workshops? Will their experience be different since the event heavily relied on the app to connect with other attendees and speakers?

I appreciated how the summit not only showcased all the fancy cool products but also emphasized on the downsides and challenges technology brings. By doing so, the summit did a good job of providing transparency. One thing that really stuck to me was when Boisvert spoke of her research findings at Limbic Lab that shows how technology is rewiring our brain. As Boisvert comments, it will be important for us to take a human-centered approach to reverse the harmful effects caused by technology. This seems to be a central theme in the summit as well as our discussions from class. As Norman, and what other speakers have repeated throughout the summit, future designers and technologists will not only need training as technicians but will also need to receive training to learn what it means to be ‘human’ (Norman, 2018).

References

Mappers Delight VR. (2017). Retrieved from: https://rapresearchlab.com/#portfolioModal2.

Norman, Don A. (1998). Being Analog. Retrieved from: http://www.jnd.org/dn.mss/being_analog.html.

NYC Media Lab ’19. (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://summit.nycmedialab.org/

Posner, Miriam (2016). What’s next: The radical, unrealized potential of digial humanities. Retrieved from: http://miriamposner.com/blog/whats-next-the-radical-unrealized-potential-of-digital-humanities/.