By Meghan Lyon

Last Friday, October 19th, I had the pleasure of observing two symposiums. I attended the first half of The Uncomfortable Archive: New York 2018 Archives Week Symposium, and the the second half of the first day of theWhitney Independent Study Program 1968-2018 50th Anniversary Symposium. These events marked my first encounter with the conference-style symposium. I have attended numerous lectures, but a presentation in the symposium format has a quality that diverges from a unique lecture; each speaker addresses their own content or area of expertise as well as the overarching concept of the day.

According to Merriam-Webster, the definition of symposium includes: “a social gathering at which there is a free interchange of ideas”; “a formal meeting at which several specialists deliver short addresses on a topic”; “a collection of opinions on a subject”; and “discussion.” Additionally, it defines a panel as “a group of persons who discuss before an audience a topic of public interest.” The panel would be the object of attention, the body expected to enlighten the audience; it could also be the platform from which information is distributed. From my observation of the symposium as an information environment, I would define it as a learning-based information environment, where the audience is an information-seeking group whose attendance is predicated on the expectation of a conference of knowledge from the panelists.

The Uncomfortable Archive Symposium, which I observed from 9:30 am through the lunch break at 1:15 pm, was devised to motivate the audience by revealing uncomfortable histories and truths about archives or loosely-defined archival materials. This goal manifested in multiple presentations about obstacles to record keeping and maintenance from autocrats, fascists, and capitalists. The Keynote Address was given by Anthony Clark, who played up the “uncomfortable” concept. Clark is an expert on presidential libraries and archives and discussed the more insidious aspects of presidential libraries—not just as propaganda machines but as active forces in politics, conservatively oriented towards maintaining the status quo of private interest groups. His address examined the unfortunate history and present mismanagement of the National Archives and Records Administration by the former director of NYPL, David Ferriero.

Clark addressed a room full of concerned professionals who were mostly cis-female, mostly white. The audience lights and stage lights were both on and remained on throughout the day; the AC was on, there was carpeting and plush chairs, there were no outlets throughout the seating area, and there was no wifi and no data service in the hall at the Center for Jewish History. There was a podium for speakers and a table for panelists; I found that every panelist was an individual speaker and the “panel” discussion was, unfortunately, just an audience Q&A directed at the group of “panelists.”

The Uncomfortable Archives Symposium was crafted as a learning environment for archivists and professionals within the field of information. Most audience members were taking notes; actively engaged and trying to learn. However, several days after the Uncomfortable Archives, a peer who was also in attendance bemoaned that there was too little discussion of problems or troubleshooting thereof from within archives; in other words, she gained no knowledge that was useful to her as a professional. Also, most talks were initiated after a precarious disclaimer: “My comments are my own and not my employers,” a common social media and web-based, personal disclaimer which has migrated towards any format that has the potential to wind up on the internet. This attempt by speakers to protect their professional status could relate to Robert Jensen’s paper, The Myth of the Neutral Professional. In order to keep their jobs, librarians and archivists are pressured to appear politically neutral. At the very least, they must attempt to be sure that they cannot be held accountable as a representative of their employer when speaking publicly. I find the disclaimers’ presence to be unsettling, and feel sorry that the speakers need to present defensively on stage.

Midday I walked over to the Whitney Museum of American Art for the ISP 50 Year Anniversary Symposium; This second observation lasted from 2:30pm – 8pm.

The Whitney Independent Study Program 50 year anniversary Symposium was a very different kind of event from the Uncomfortable Archive; It was not technically a professional event. The intended audience was ISP alumni, but the ISP program is so popular that many others were also in the audience. The 2-day event was both open to the public and free, so it drew contemporary art enthusiasts, fans of panelists, social climbers, artists, museum workers, art historians, current university students, and people in some way involved in the art world who are hungry for continued education. Because of the various points of entry, there was also a more diverse demographic. It was so packed in the lecture hall that overflow seating was made available in the Tom and Diane Tuft Trustee Room on the 8th floor, which is where I wound up for the first panel that I witnessed.

In the trustee room, there was a monitor playing a livestream of the symposium as it occurred downstairs. This room quickly filled up, although it wasn’t totally full and people wandered in and out. There was an odd phenomenon of 8th floor of attendees clapping when speakers concluded, even though the presenters were on tv.

Another unexpected occurrence (unexpected to the Whitney staff, at least) was that people who showed up at the beginning of the symposium did not leave. This created a major occupancy problem, because people who registered beforehand, or who were ISP alum, could not enter. I believe that the organizers thought that people would come for a panel, or a particular speaker, and then leave—grossly underestimating the major interest in this kind of educational experience. After witnessing this symposium, I would conclude that multitudes of people are craving high quality, free, educational experiences. The panelists in this case were key figures in art theory, writing, criticism, contemporary studio practice, and pedagogy, and it is too often an exclusive few who are able to interact with the brilliance associated with the ISP milieu.

Like the Uncomfortable Archives’ attendees, nearly every audience member had a notebook out, although I would say the note-taking at the Whitney was a little more feverish, on both the 8th and 3rd floors. Eventually, a few people from the 8th floor went down in between panels to try and claim a few abandoned seats.

I made it into the lecture hall for the Pedagogy and Critical Practice panel. The structure of the panels were similar to those of the earlier symposium; each member of the panel gave a short presentation with slides, however, instead of a Q&A afterwards, there was a moderated discussion on the overarching theme of the panel, with a short time for audience questions. The time-ratio weighed heavily on the lectures, clocking in at almost 2 hours of serial lectures per 20 minutes of panel discussion.

A little earlier in the evening, curator Johanna Burton had referenced “embodied learning”—which she described as something along the lines of “trying out learning through new experiences.” I thought this would be a good opportunity to explore Marcia J. Bates’ paper Fundamental Forms of Information. I could see note-taking as an interaction with recorded information, “communicatory or memorial information preserved in a durable medium,” (Bates 14) as well as an enactment of student/teacher paradigm, and an attempt to fill a knowledge-seeking need. The symposium could be examined as a place for the expression of recorded information (lectures) to be

embodied by an audience through listening and interpretation, and then enacted by their future selves as more knowledgable beings.

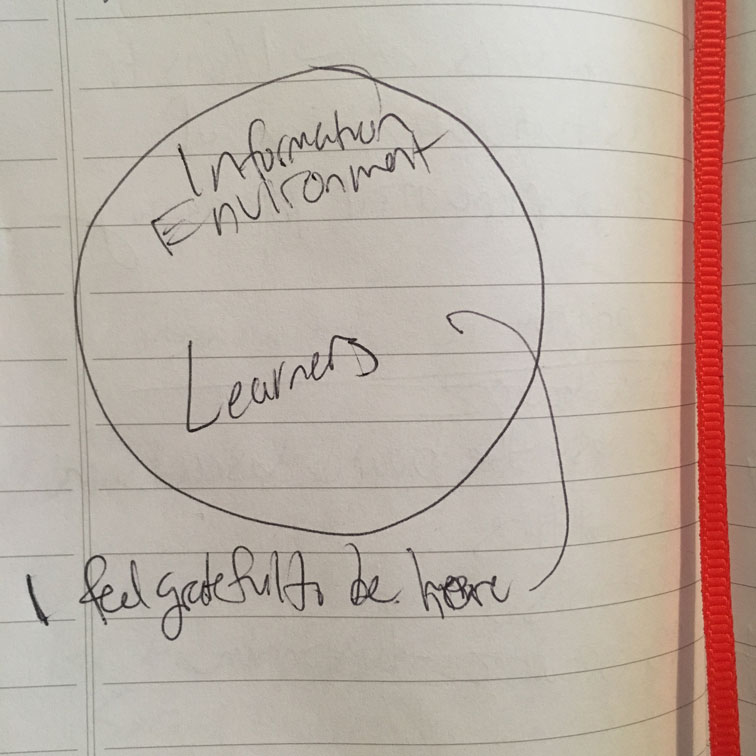

Nearing the end of the ISP Symposium, Mary Kelly took the stage. Kelly was the only speaker who did not use a slide-show presentation, and she was so soft spoken yet captivating, you could feel the entire audience leaning in and opening up. I drew a small diagram of the environment and how I felt.

Sources:

Bates, M. (2006). Fundamental Forms of Information. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(8) (2006): 1033-1045

Jensen, R. (2006). The Myth of the Neutral Professional. Lewis, A. (Ed.), Questioning Library Neutrality: Essays from Progressive Librarian. (pp. 89-96). Duluth, MN: Library Juice Press.