by Jay Rosen

I recently attended a presentation and panel discussion at this year’s Lapidus Center Conference on Enduring Slavery, hosted on October 10-12 by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at New York Public Library. The theme of this year’s conference was “Resistance, Public Memory, and Transatlantic Archives,” which I thought might connect to some of our previous discussions on archives, cultural preservation, and collective memory in the United States.

The particular session I attended was entitled, “Emerging Perspectives on Public Memory and Popular Representations of Anti-Black Violence.” The conversation was introduced by Jennifer DeClue, Assistant Professor in the Program for the Study of Women and Gender at Smith College, who also presented original research and moderated the subsequent discussion.[1] Other panelists included Dr. Tyler Perry, Assistant Professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and Dr. Allison Page, Assistant Professor of Media and Cultural Studies at Old Dominion University. Because the material presented in DeClue’s presentation was especially interesting to me, I’ve decided to focus exclusively on that here.

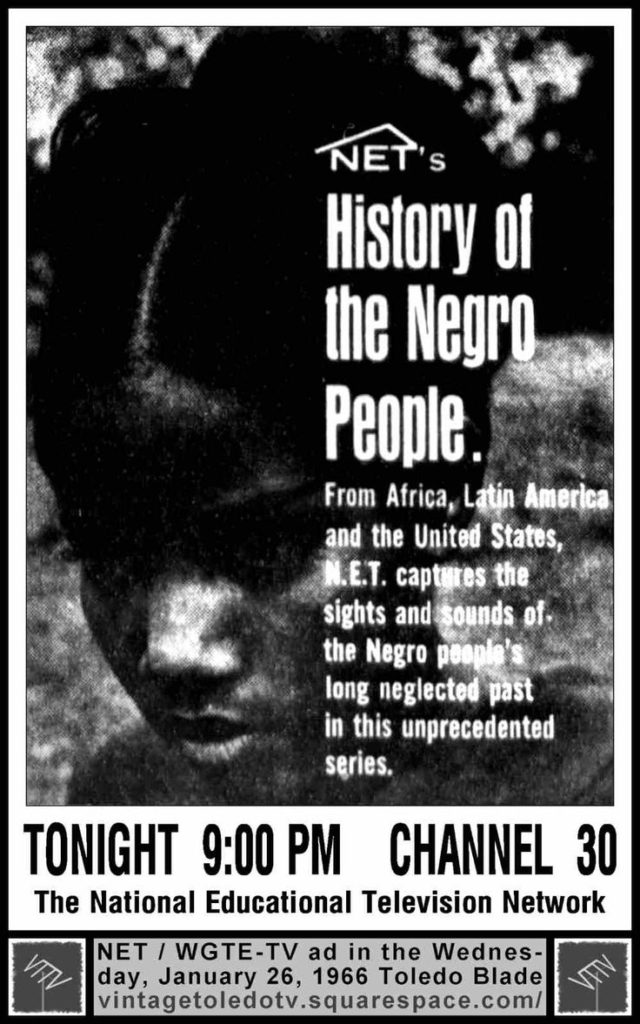

The title of DeClue’s presentation was “Staging Slavery: Public Television and the Performance of Slave Narratives.” Her discussion centered on “The History of the Negro People,” a 9-part televison series which aired on the public television network NET (now PBS) in 1965. The series explored lesser known narratives of black people in America and throughout the world, featuring episodes on ancient African civilizations, the racial history of the American south, and the experience of black people in Brazil, among other topics.

The episode discussed by DeClue is simply titled “Slavery.” Included in it are staged dramatizations of slavery that emphasize resistance; significantly, these dramatizations were based on the actual stories of enslaved people in America. The testimonies used in “Slavery” were collected as part of FDR’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) program in the 1920s. Though the WPA is mostly remembered for grand-scale public works projects like the construction of highways and buildings, it also included the Federal Writers Project, which facilitated the collection of American folklore and oral histories. As DeClue put it, a “database” of oral histories by formerly enslaved people was amassed through these efforts. The “raw material” embodied in these histories was then reanimated through the dramatic performances described by DeClue, and given a national audience through the medium of public television.

As previously mentioned, “Slavery” primarily highlighted instances of resistance to slaveholders and the institution of slavery itself. The episode included re-tellings of the stories of infamous rebels Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, and John Brown, as well as narratives of lesser known enslaved people who dared challenge the “peculiar institution.” In chronicling American slavery through the lens of resistance and using the words of people who endured it, the episode marks an “intervention into the dominant narrative of slavery,” shifting our public memory of slavery away from narratives of servility and complacency and towards tales of humanity and resilience.

The excerpts from “Slavery” that DeClue played for the audience highlight the potency of archives, as well as their insurrectionary potential. More specifically, they demonstrate that archives contain material that can be used to disrupt dominant understandings of history and uplift the narratives of marginalized people. As the Schwartz and Cook reading we were assigned earlier this semester suggests, archives have tremendous power in shaping our collective memory and identity, and can be used as tools to promote hegemony or resistance, depending on the materials available and the objectives of those who use them.

At one point, DeClue mentioned that Federal Writers Project employees discovered that former slaves were less likely to be as forthcoming with white interviewers as they were with black ones. This unsurprising fact demonstrates that the archival record is anything but an unmediated collection of stories and documents. Rather, the records available to us today were shaped — implicitly and explicitly — by the people in positions to receive, create, and preserve them. As DeClue reminded us, it’s remarkable that so many powerful and subversive stories were collected by this project, given that most interviewers were white and were thus received less comfortably by black storytellers. What might this archival record look like if only black people collected these histories?

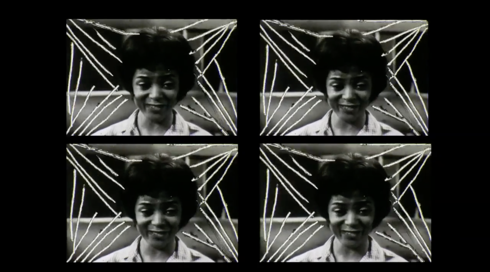

In closing out her presentation, Jennifer brought up the avant-garde short film “An Ecstatic Experience,” created by Brooklyn-based artist and filmmaker Ja’Tovia Gary. The film repurposes footage from “Slavery,” overlaying etchings, drawings, and other markings over images from the 1965 segment. In manipulating this footage, Gary added yet another “layer” to the archive and underscored the fact that archival materials evolve over time and in response to current understandings of the issues they embody and reflect. I found it exciting (and a bit dizzying) to try and peel back the archival “layers” included in DeClue’s presentation. For one, there are the narratives collected by the Federal Writers Project — these testimonies themselves comprise a kind of “transatlantic archive,” as DeClue put it. There is then the archival repository represented in “The History of the Negro People,” now over fifty years old. From there “An Ecstatic Experience” was born, further commenting on and repurposing the “raw material” collected by the Federal Writers Project in the 1920s. Finally, there is DeClue’s own analysis of these “layers,” which has already been digitally archived on Vimeo, in addition to my own commentary on her recent discussion, now archived on WordPress. These various “layers” enliven my understanding of archival “provenance” as introduced in the Caswell reading assigned earlier this semester. They show how records and archives are far from static, but rather unfold over decades and in conversation with the past and present.

Works referenced / cited:

Bly, L., & Wooten, K. (Eds.). (2012). Make your own history: Documenting feminist and queer activism in the 21st century. Los Angeles, CA: Litwin Books.

Caswell, M. L. (2016). “’The Archive’ Is Not an Archives: On Acknowledging the Intellectual Contributions of Archival Studies.” Reconstruction, 16 (1), 1-12. Retrieved from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bn4v1fk.

Schwartz, J. M., & Cook, T. (2002). Archives, records, and power: The making of modern memory. Archival Science, 2(1–2), 1–19. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435628

[1] Side note: DeClue mentioned during her introduction that she is currently working on a book titled “Visitation: Towards a Black Feminist Avant-Garde Cinema,” which focuses on black women filmmakers who use archival documents and avant-garde filmmaking techniques to encourage different ways of perceiving black women. This project brought to mind Alana Kumbier’s article “Inventing History: The Watermelon Woman and Archive Activism.” Kumbier’s article analyzes Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman, in which Cheryl — represented as filmmaker but also a character in the film — traces a fictional persona named Fae Richards largely in order to “create a documentary heritage for black lesbian cultural production to enable future products” (Kumbier 103). Thus, both women use archival materials and the medium of film to encourage nuanced and feminist depictions of black women.